|

Historical Information

Approximately seventy five miles to the north of the Fort

Gratiot Light, a shallow reef with only two feet of water above

its outer end protruded from the shore a full two miles into Lake

Huron's waters. While such a reef would have been a hazard to vessels

coasting the western Huron shore under the best of circumstances, it's

location was particularly egregious, as it stretched across the exact

point at which northbound vessels began their westerly swing into

Saginaw Bay.

Taking up the cry from maritime

interests to mark the hazardous reef, on February 19, 1838 Michigan

State Representative Isaac Crary entered a motion in Congress that the

Committee on Commerce be instructed to investigate into the expediency

of establishing a lighthouse on the nearby shore to both warn mariners

of the reef and to mark the important turning point into Saginaw Bay.

After investigation, the Committee concurred, and Congress responded

with an appropriation of $5,000 for the Light's construction on July 7,

1838.

While conducting his annual inspection

of lighthouses on the lakes and selecting sites for proposed new

stations a month later, Lieutenant James T Homans arrived in the area to

select the site for the new station. In his report to the Fifth Auditor

of the Treasury for the year, Homans reported that he selected "the

most westerly of the two points, known as Point-aux-Barques, near the

entrance to Saganaw Bay (sic), for the light there, because it is sooner

seen by vessels approaching from the northward and westward, by which it

will be most used; also, as being near a shoal, dangerous to the

navigation of its vicinity." Homans went on to report that

"There is stone in considerable quantity near this location, which

can be used in constructing the buildings. The land, I presume, belongs

to the Government, or can be had for a moderate price, there being no

settlements within several miles, and the soil very barren."

Construction of the lighthouse was not

completed until 1847, with the light not exhibited until the opening of

the following season of navigation. Peter L. Shook was appointed as the

station's first Keeper, and is listed in payroll records as arriving at

the station on March 6, 1848, and thus it is likely he exhibited the

Pointe Aux Barques Light for the first time soon thereafter. We have

thus far been able to determine very little about the structures that

originally made up the station. However it is likely that they were

similar in design to other early stations built during the period,

consisting of a squat stone tower outfitted with a Lewis Lamp array, and

a small detached dwelling of either brick or stone. Construction of the lighthouse was not

completed until 1847, with the light not exhibited until the opening of

the following season of navigation. Peter L. Shook was appointed as the

station's first Keeper, and is listed in payroll records as arriving at

the station on March 6, 1848, and thus it is likely he exhibited the

Pointe Aux Barques Light for the first time soon thereafter. We have

thus far been able to determine very little about the structures that

originally made up the station. However it is likely that they were

similar in design to other early stations built during the period,

consisting of a squat stone tower outfitted with a Lewis Lamp array, and

a small detached dwelling of either brick or stone.

Peter Shook passed away on May 15 of

the following year, and his wife Catherine appointed as Keeper on his

death. Evidently Catherine took well to lighthouse keeping, as Henry B

Miller, the Superintendent and Inspector of Lights for the Northwest

Lakes inspected her station on July 2, 1850 and reported everything to

be in "passable order" and the "conduct of the Keeper

good." However, it would appear that the work quickly took its toll

on Catherine, as she resigned from lighthouse service on March 19, 1851,

to be replaced by Francis H Sweet. As was frequently the case with most

of the early lighthouses built on the Great Lakes, the quality of

construction and materials used in the original structures were

marginal, and with the diminutive tower no longer deemed an effective

adequate guide to the increasing maritime commerce into Saginaw Bay, the

decision was made to destroy the old structure and to erect both an

improved tower and dwelling. Peter Shook passed away on May 15 of

the following year, and his wife Catherine appointed as Keeper on his

death. Evidently Catherine took well to lighthouse keeping, as Henry B

Miller, the Superintendent and Inspector of Lights for the Northwest

Lakes inspected her station on July 2, 1850 and reported everything to

be in "passable order" and the "conduct of the Keeper

good." However, it would appear that the work quickly took its toll

on Catherine, as she resigned from lighthouse service on March 19, 1851,

to be replaced by Francis H Sweet. As was frequently the case with most

of the early lighthouses built on the Great Lakes, the quality of

construction and materials used in the original structures were

marginal, and with the diminutive tower no longer deemed an effective

adequate guide to the increasing maritime commerce into Saginaw Bay, the

decision was made to destroy the old structure and to erect both an

improved tower and dwelling.

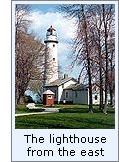

The contract for the new station was

awarded to Milwaukee contractors Sweet, Ransom and Shinn in 1854, who

were simultaneously awarded contracts for building a number of

lighthouses on the Great Lakes, including the LaPointe Light on Lake

Superior, which was erroneously erected on Michigan

Island. Plans for

the new Pointe Aux Barques station called for a Cream City Brick tower

standing 89 feet from the foundation to the top of the lantern

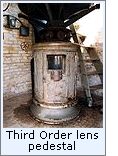

ventilator ball. The lantern was outfitted with a Third

Order Fresnel lens which exhibited a characteristic fixed white

light varied by a bright a white flash every two minutes. To impart the

desired characteristic, the lens was outfitted with bulls eye panels and

was situated atop a cast iron pedestal. A clockwork motor rotated the

lens around the lamp at an exact rotational speed which placed the bulls

eyes between the mariner and the lamp every 2 minutes, creating a bright

flash.

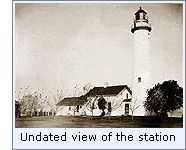

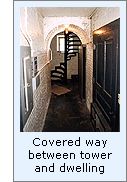

With the tower constructed atop a twelve foot high bluff at the

point, the lens stood at a focal plane of 93 feet above lake level, and

was visible for a distance of 16 miles at sea. The two story dwelling

was attached to the tower by way of a covered passageway, outfitted with

an arch topped cast iron door at the tower end to stem the possible

spread of fire between the two structures Work on the station was

complete and the Third Order Fresnel exhibited for the first time on an

unrecorded evening in 1857, and no longer serving any purpose the old

tower and dwelling were demolished. After three years, the bluff on

which the station was constructed was found to be deteriorating, and a

revetment was installed at the water line to serve as a protection from

the waves. While the appointment of Assistant Keepers was frequently

reserved for offshore stations and those with fog signals, the decision

was made to add an Assistant at the station, with Mr. G Dodge arriving

to fill the position with the opening of the navigation season in 1859. With the tower constructed atop a twelve foot high bluff at the

point, the lens stood at a focal plane of 93 feet above lake level, and

was visible for a distance of 16 miles at sea. The two story dwelling

was attached to the tower by way of a covered passageway, outfitted with

an arch topped cast iron door at the tower end to stem the possible

spread of fire between the two structures Work on the station was

complete and the Third Order Fresnel exhibited for the first time on an

unrecorded evening in 1857, and no longer serving any purpose the old

tower and dwelling were demolished. After three years, the bluff on

which the station was constructed was found to be deteriorating, and a

revetment was installed at the water line to serve as a protection from

the waves. While the appointment of Assistant Keepers was frequently

reserved for offshore stations and those with fog signals, the decision

was made to add an Assistant at the station, with Mr. G Dodge arriving

to fill the position with the opening of the navigation season in 1859.

By 1867, the town of Port Huron 75

miles to the south was growing rapidly as a major maritime and railway

transfer point. With the number of lights around the railway depots

close to the Fort Gratiot Light increasing, mariners seeking the

entrance to the River were concerned that the fixed white light at Fort

Gratiot might be confused with the locomotive headlights in the area. To

eliminate the possible confusion, the flashing lens from Pointe Aux

Barques was removed and shipped to Port Huron, where it was installed in

the Fort Gratiot lantern. On completion of the installation, the fixed

Third order lens from Fort Gratiot was in turn shipped to Pointe Aux

Barques where it was installed in that station's lantern. Also in this

year, it was noted that large trees were encroaching on the lighthouse

reservation, and that they would need to be removed before visibility of

the light was compromised. By 1867, the town of Port Huron 75

miles to the south was growing rapidly as a major maritime and railway

transfer point. With the number of lights around the railway depots

close to the Fort Gratiot Light increasing, mariners seeking the

entrance to the River were concerned that the fixed white light at Fort

Gratiot might be confused with the locomotive headlights in the area. To

eliminate the possible confusion, the flashing lens from Pointe Aux

Barques was removed and shipped to Port Huron, where it was installed in

the Fort Gratiot lantern. On completion of the installation, the fixed

Third order lens from Fort Gratiot was in turn shipped to Pointe Aux

Barques where it was installed in that station's lantern. Also in this

year, it was noted that large trees were encroaching on the lighthouse

reservation, and that they would need to be removed before visibility of

the light was compromised.

While the decision to swap lenses with

Fort Gratiot solved the problem at the southern station, it was

evidently not deemed as acceptable as a long term solution to mariners

navigating in and out of Saginaw Bay, as Senator Zachariah Chandler

presented a petition signed by concerned vessel masters before the

Senate on February 7, 1872 requesting that the characteristic of the

Pointe Aux Barques be changed back to a flashing light. Unfamiliar with

the intricacies of navigational issues on the distant lake, the mater

was referred to the Committee on Commerce for analysis. Evidently the

Committee on Commerce concurred with the spirit of the petition, for the

Third Order Lens at Pointe Aux Barques was again replaced the following

year with a flashing white light showing its flash every ten seconds.

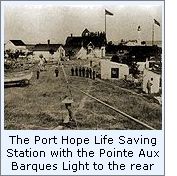

With an expansion of the Life Saving

Service throughout the lakes, 1875 saw the establishment of the Port

Hope Life Saving Station on the lighthouse reservation some 800 feet to

the south of the tower. Constructed to a plan drawn by Life Saving

Service Engineer Francis Chandler, the building was particularly

beautiful, with diagonal bracing on the exterior walls and intricate

bracketing supporting the overhanging eaves. Captain J. H. Crouch was appointed as the Keeper

of the new Life Saving station, and it is likely that lighthouse Keeper

Andrew Shaw appreciated having the Life Savers close by, as it would

have provided him the opportunity for a little socialization beyond his

family previously unavailable on the isolated point, and as a Federal

employee he likely enjoyed the availability of a peer's shoulder on

which to complain about government pay rates and regulations! With an expansion of the Life Saving

Service throughout the lakes, 1875 saw the establishment of the Port

Hope Life Saving Station on the lighthouse reservation some 800 feet to

the south of the tower. Constructed to a plan drawn by Life Saving

Service Engineer Francis Chandler, the building was particularly

beautiful, with diagonal bracing on the exterior walls and intricate

bracketing supporting the overhanging eaves. Captain J. H. Crouch was appointed as the Keeper

of the new Life Saving station, and it is likely that lighthouse Keeper

Andrew Shaw appreciated having the Life Savers close by, as it would

have provided him the opportunity for a little socialization beyond his

family previously unavailable on the isolated point, and as a Federal

employee he likely enjoyed the availability of a peer's shoulder on

which to complain about government pay rates and regulations!

1881 was one of the driest summers on

record, and a wildfire sprang up and raged out of control in Michigan's

Thumb area. Driven by westerly winds, the fire made its way inexorably

toward the Huron shore, with both the Port Hope Life Saving Station and

Pointe Aux Barques Light standing directly in its path with their backs

against the shore. Keeper Shaw nervously watched as the fire approached

from the east, fearing both for the safety of his Light and his family

farm a mile to the north. Shaw and the Life Savers fought valiantly to

keep the fire from the tower carrying water from the lake in every

container they could lay their hands upon. With the fire at the

lighthouse under control, they then turned their attention to Shaw's

farm. Arriving to find the buildings and crops completely obliterated,

Shaw was no doubt elated to find his family had some how made it through

the ordeal unscathed. On their return to the lighthouse, they found the

wind had shifted, with the flames now threatening the Life Saving

Station. A bucket brigade was formed and the shingle roof was

wetted-down to prevent ignition by errant sparks. Finally the wind

shifted offshore, pushing the fire back on itself and out of the area.

One can only imagine the relief that must have been felt by all involved

after such a fight for both their lives and their livelihoods.

A work crew arrived at the station in

1884 and drilled and blasted a well 19 feet through the rock to supply

water to the lighthouse. 1891 saw the construction of a woodshed for the

Keeper's use, and the following year, the materials for a round iron oil

storage shed were delivered at the Detroit depot. The materials, along

with a work crew, were delivered at the station aboard the lighthouse

tender AMARANTH in

1893, with the shed was erected a short distance to the south of the

tower. While fogs in the area were not considered worthy of the erection

of a first class steam fog signal at the station, an automated

fog bell was installed at the station in 1899 to be operated

during periods of thick weather. At the close of the 1900 season of

navigation, the District Lampist arrived at the station, disassembled

the Third Order lens and took it to the lamp shop at the Detroit Depot,

where it was completely overhauled during the winter, and then returned

to the station on the opening of the 1901 season of navigation. A work crew arrived at the station in

1884 and drilled and blasted a well 19 feet through the rock to supply

water to the lighthouse. 1891 saw the construction of a woodshed for the

Keeper's use, and the following year, the materials for a round iron oil

storage shed were delivered at the Detroit depot. The materials, along

with a work crew, were delivered at the station aboard the lighthouse

tender AMARANTH in

1893, with the shed was erected a short distance to the south of the

tower. While fogs in the area were not considered worthy of the erection

of a first class steam fog signal at the station, an automated

fog bell was installed at the station in 1899 to be operated

during periods of thick weather. At the close of the 1900 season of

navigation, the District Lampist arrived at the station, disassembled

the Third Order lens and took it to the lamp shop at the Detroit Depot,

where it was completely overhauled during the winter, and then returned

to the station on the opening of the 1901 season of navigation.

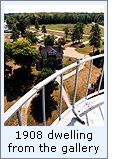

With the turn of the twentieth century,

it was realized that the single dwelling provided for the Keeper and his

Assistant at the Point Aux Barques station was wholly inadequate, and

plans were drawn up for the erection of a second dwelling. Built on the

same plan as structures concurrently being planned for Munising

and Grand Marais,

work on the new dwelling began at the end of May, 1908, with the

blasting of the cellar and sewer line to the lake. By the end of June,

blasting was complete and the foundation had been built to ground level.

Work progressed rapidly over the following months, and was brought to

completion on August 7, with then Head Keeper Peter Richards taking up

residence soon thereafter. With the turn of the twentieth century,

it was realized that the single dwelling provided for the Keeper and his

Assistant at the Point Aux Barques station was wholly inadequate, and

plans were drawn up for the erection of a second dwelling. Built on the

same plan as structures concurrently being planned for Munising

and Grand Marais,

work on the new dwelling began at the end of May, 1908, with the

blasting of the cellar and sewer line to the lake. By the end of June,

blasting was complete and the foundation had been built to ground level.

Work progressed rapidly over the following months, and was brought to

completion on August 7, with then Head Keeper Peter Richards taking up

residence soon thereafter.

After construction of the new dwelling,

things remained fairly uneventful at the station, with only general

ongoing maintenance and minor changes being undertaken. The illumination

was upgraded with the installation of an incandescent oil vapor lamp

system (IOV) on June 28, 1914. Without change in characteristic, the

installation represented a significant upgrade in the light's visibility

as the light's intensity was increased to 34,000 candlepower and its

range of visibility to 18 miles at sea. A lighted bell buoy was placed

in 36 feet of water 2 ¼ miles offshore to mark the eastern extremity of

the reef on May 22, 1918. Consisting of a cylindrical float with a

skeletal superstructure supporting a ten candlepower light ten feet

above the water, the light was fueled by an acetylene system and the

bell operated by wave action. Designed to carry enough acetylene to

power the light for almost the entire season of navigation, the buoy was

taken up at the close of the season of navigation each year by the

lighthouse tender AMARANTH, and taken to the Detroit for maintenance and

painting, and then replaced at the opening of navigation the following

year. After construction of the new dwelling,

things remained fairly uneventful at the station, with only general

ongoing maintenance and minor changes being undertaken. The illumination

was upgraded with the installation of an incandescent oil vapor lamp

system (IOV) on June 28, 1914. Without change in characteristic, the

installation represented a significant upgrade in the light's visibility

as the light's intensity was increased to 34,000 candlepower and its

range of visibility to 18 miles at sea. A lighted bell buoy was placed

in 36 feet of water 2 ¼ miles offshore to mark the eastern extremity of

the reef on May 22, 1918. Consisting of a cylindrical float with a

skeletal superstructure supporting a ten candlepower light ten feet

above the water, the light was fueled by an acetylene system and the

bell operated by wave action. Designed to carry enough acetylene to

power the light for almost the entire season of navigation, the buoy was

taken up at the close of the season of navigation each year by the

lighthouse tender AMARANTH, and taken to the Detroit for maintenance and

painting, and then replaced at the opening of navigation the following

year.

1932 saw the electrification of the

station and the installation of an incandescent electric bulb within the

Third Order Fresnel lens, providing a further increase in output to

120,000 candlepower. At this time, the characteristic flash rate was

also changed to exhibit a 3 second flash followed by a 7 second eclipse.

With electrification and Coast Guard's assumption of responsibility for

the nation's aids to navigation in 1939, the way was paved for complete

automation. At some time in the early 1950's, the Third Order Fresnel

was disassembled and crated-up for storage and replaced with twin DCB-224

aero beacons with automatic bulb changers, which were installed

on the old cast iron pedestal. Emitting two 5-second flashes followed by

a 20-second eclipse. 1932 saw the electrification of the

station and the installation of an incandescent electric bulb within the

Third Order Fresnel lens, providing a further increase in output to

120,000 candlepower. At this time, the characteristic flash rate was

also changed to exhibit a 3 second flash followed by a 7 second eclipse.

With electrification and Coast Guard's assumption of responsibility for

the nation's aids to navigation in 1939, the way was paved for complete

automation. At some time in the early 1950's, the Third Order Fresnel

was disassembled and crated-up for storage and replaced with twin DCB-224

aero beacons with automatic bulb changers, which were installed

on the old cast iron pedestal. Emitting two 5-second flashes followed by

a 20-second eclipse.

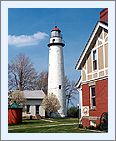

No longer needing to maintain a

presence in the area, the Cost Guard removed its crew from the station,

and mothballed the building, making only infrequent trips to the tower

to service the DCB-224's. The lighthouse reservation was sold to Huron

County in 1958 to be operated as a park, campground and lighthouse

museum, in which capacity it continues to operate to this day. No longer needing to maintain a

presence in the area, the Cost Guard removed its crew from the station,

and mothballed the building, making only infrequent trips to the tower

to service the DCB-224's. The lighthouse reservation was sold to Huron

County in 1958 to be operated as a park, campground and lighthouse

museum, in which capacity it continues to operate to this day.

The station's venerable Third Order

Fresnel lens was displayed at the Grice museum in Harbor Beach for a

number of years until that museum obtained the Fourth Order lens from

the Harbor Beach Breakwater

Light. The Third Order lens was subsequently moved to the Huron

City museum, where it is displayed to this day, along with a fog bell

that also likely came from the Pointe Aux Barques station.

Keepers of

this Light

Click here

to see a complete listing of all Pointe aux Barques Light keepers

compiled by Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Seeing the Light

Located in the county park 10 miles east of Port Austin. The park

features a beautiful campground and many picnic areas. The lighthouse museum is open daily from

Memorial Day through Labor Day from 12:00 p.m. - 4:00 p.m.

Contact information

Since April 2002, the

Friends of

the Pointe Aux Barques Lighthouse Society has been working in concert

with the county to restore and interpret the lighthouse. For additional

information, contact

Pointe Aux Barques Lighthouse

Society

8114 Rubicon Road

Port Hope, MI 48468-9759

Telephone: (989) 428-2010

Website:

www.pointeauxbarqueslighthouse.org

Email:

info@pointeauxbarqueslighthouse.org

Reference

Sources

Annual report of the Life Saving Service, 1882 Annual report of the Life Saving Service, 1882

Annual reports of the Fifth Auditor of the Treasury, 1838 & 1850

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Board, various, 1860 - 1909

Annual reports of the Lake Carriers Association, various, 1914 - 1920

USCG Historian's Office - photographic archives.

Personal visit to Pointe Aux Barques, 05/05/00 & 9/14/02

Photographs from the author's personal collection.

Keeper listings for this light appear

courtesy of Tom & Phyllis Tag

|