|

Historical Information

While the discovery of iron ore would soon cause the ports of

Duluth/Superior and Marquette to assume the role of Superior's

preeminent ports, in 1850 the bustling fur trading center at La Pointe

on Madeline Island served as the lake's hub of maritime commerce.

Although the harbor at LaPointe was protected from deadly Superior

Nor'westers by its situation in the lee of the Apostle Islands, and from

Northeasterly blows by the body if Madeline Island itself, entry into

the harbor was no simple task from any direction.

Captains

making for La Pointe from the east were forced to thread the needle

through the narrow South Channel between Long Island and the southerly

tip of Madeline Island, before swinging northwest into more open water,

and thence to the harbor at LaPointe. Vessels wishing to avoid the South

Channel by swinging around the northerly end of Madeline Island were

forced instead to negotiate between the Madeline coast and Michigan,

Stockton, and Basswood Islands before swinging south to LaPointe. Given

the choice, almost all captains chose the route through the South

Channel, since it was a considerably shorter distance. Shorter distances

meant less time, and even in the mid nineteenth century commercial

captains were only too aware of the fact that time was money. While

making the passage through the South Channel under sail was difficult

under the best of conditions, without the benefit of a light to mark the

westerly tip of Long Island, the task was formidable under darkness or

in thick weather of any kind. Captains

making for La Pointe from the east were forced to thread the needle

through the narrow South Channel between Long Island and the southerly

tip of Madeline Island, before swinging northwest into more open water,

and thence to the harbor at LaPointe. Vessels wishing to avoid the South

Channel by swinging around the northerly end of Madeline Island were

forced instead to negotiate between the Madeline coast and Michigan,

Stockton, and Basswood Islands before swinging south to LaPointe. Given

the choice, almost all captains chose the route through the South

Channel, since it was a considerably shorter distance. Shorter distances

meant less time, and even in the mid nineteenth century commercial

captains were only too aware of the fact that time was money. While

making the passage through the South Channel under sail was difficult

under the best of conditions, without the benefit of a light to mark the

westerly tip of Long Island, the task was formidable under darkness or

in thick weather of any kind.

Wisconsin Senator Orasmus Cole took up

the cause of maritime interests on February 8, 1851, when he presented a

memorial before Congress on behalf of the Wisconsin Legislature praying

"for an appropriation to build a light-house at La Pointe, on the

southern shore of Lake Superior." Congress appropriated $5,000 for

the construction of the LaPointe light on March 3, 1853, and by the end

of that year plans for the station had been drawn up, a site was

selected, and steps were underway to obtain title for the reservation.

However, as a result of a series of government blunders, the light which

was built in 1857 to satisfy the appropriation was mistakenly built on

Michigan Island, and since no keepers were ever assigned to the station,

it appears likely that it was never truly placed into service. To

recover from the error, plans were quickly arranged to build a station

on the northwestern end of Long Island, as originally specified in the

appropriation.

In accordance with the original

specifications for the LaPointe Light, the station erroneously built on

Michigan Island by Milwaukee contractors Sweet, Ranson, and Shinn

consisted of a substantial stone dwelling and attached stone tower.

Since all of the $5,000 appropriation had been spent at Michigan Island,

there were no additional funds appropriated for the light now needed to

be built on Long Island. As a result, construction costs were kept to a

bare minimum through the erection of a simple wood frame combination

keepers dwelling and light tower. Under normal circumstances, such an

insubstantial structure would have been considered unsuitable for such

an exposed location, however the Eleventh District was "under the

gun" to deliver the station as authorized by Congress, and

accommodations were necessarily made to recover from the error. Whether

the costs of the new station were born by Sweet, Ranson and Shinn,

whether or they were hidden within other projects being undertaken in

the Eleventh District at the time, we have been unable to determine,

however the LaPointe Light was finally built in 1858 on a slight rise

approximately 400 yards from the northwesterly tip of the island.

The

clapboard-sided 1½-story structure was erected on a square timber

foundation, and incorporated a short tower integrated into one end of

the roof. With the top of the tower standing only 34 feet above the

foundation, the octagonal cast iron lantern was outfitted with a fixed

red Fourth Order Fresnel lens at a focal plane of 52 feet by virtue of the

building's location on slightly elevated ground, in turn affording the

light a visible range of 12 miles in clear weather. The combination of

the timber foundation and the sand on which it stood proved to be

problematic after only five years. High winds were found to be blowing

the sand away from beneath the foundation timbers, creating an unstable

condition through which it was feared that the building might soon be

completely undermined and collapse. In order to effect a solution, a

crew arrived on Long Island in 1864 and installed cast iron pipe

supports on stone piers beneath the building to provide support for the

foundation timbers. However, during his annual inspection of lights in

the district the following year, the Eleventh District Inspector

reported that the problem was not completely solved, and he recommended

that the sand around the foundation be covered with a layer of broken

stone to help minimize continued erosion.

A

contract was awarded for the procurement, transportation and

installation of the crushed stone in 1866, but it was not quarried on

Raspberry Island and delivered to Long Island until late in 1868, where

all 50 cords sat in piles until the following year, when they were

finally crushed and distributed around the building foundation. While

the project took considerably longer than expected, it appears to have

been successful, since in his report for 1869, the District Inspector

reported simply that the repair was "effectual." With maritime

traffic patterns changing to the north of Madeline Island, in that same

year the Lighthouse Board decided to activate a fixed white light in the

Michigan Island lighthouse, which had been sitting unused since its

construction in 1857, and at the same time the characteristic of the

LaPointe light was changed to fixed red, in order to better

differentiate the two stations. A

contract was awarded for the procurement, transportation and

installation of the crushed stone in 1866, but it was not quarried on

Raspberry Island and delivered to Long Island until late in 1868, where

all 50 cords sat in piles until the following year, when they were

finally crushed and distributed around the building foundation. While

the project took considerably longer than expected, it appears to have

been successful, since in his report for 1869, the District Inspector

reported simply that the repair was "effectual." With maritime

traffic patterns changing to the north of Madeline Island, in that same

year the Lighthouse Board decided to activate a fixed white light in the

Michigan Island lighthouse, which had been sitting unused since its

construction in 1857, and at the same time the characteristic of the

LaPointe light was changed to fixed red, in order to better

differentiate the two stations.

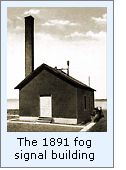

To help the station serve during

pea-soup fogs which frequently enveloped the area, $15,000 was requested

for a steam fog signal on the island in 1888, and while Congress granted

its approval for the project that same year, it failed to appropriate

the necessary funds for construction until March 2, 1889. A site for the

new facility was selected approximately three quarters of a mile east of

the Light, and contracts for a pair of ten-inch steam whistles and the

necessary building materials were awarded. While all materials arrived

at the Detroit depot early in 1890, clear title to the selected site was

not obtained until late that summer, and thus construction did not begin

until October, when the materials were loaded on the steamer RUBY and

transported to the LaPointe work site. Likely as a result of

unseasonably mild temperatures, work on the fog signal continued

throughout the winter, was completed in January of 1891, and placed into

active service with the arrival of an assistant keeper to the station in

March of that year. The signal was assigned a repeated thirty second

characteristic, consisting of a five-second blast followed by 25 seconds

of silence echoing across the lake during thick weather. That first

year, the signal was in operation some 189 hours, with the station's

hungry boilers consuming 12 tons of coal. To help the station serve during

pea-soup fogs which frequently enveloped the area, $15,000 was requested

for a steam fog signal on the island in 1888, and while Congress granted

its approval for the project that same year, it failed to appropriate

the necessary funds for construction until March 2, 1889. A site for the

new facility was selected approximately three quarters of a mile east of

the Light, and contracts for a pair of ten-inch steam whistles and the

necessary building materials were awarded. While all materials arrived

at the Detroit depot early in 1890, clear title to the selected site was

not obtained until late that summer, and thus construction did not begin

until October, when the materials were loaded on the steamer RUBY and

transported to the LaPointe work site. Likely as a result of

unseasonably mild temperatures, work on the fog signal continued

throughout the winter, was completed in January of 1891, and placed into

active service with the arrival of an assistant keeper to the station in

March of that year. The signal was assigned a repeated thirty second

characteristic, consisting of a five-second blast followed by 25 seconds

of silence echoing across the lake during thick weather. That first

year, the signal was in operation some 189 hours, with the station's

hungry boilers consuming 12 tons of coal.

By the last decade of the nineteenth

century, it became clear that the diminutive 34-foot tall tower of the

LaPointe light was no longer serving the needs of maritime traffic

passing between Madeline, Stockton and Michigan Islands. Located too far

to the west, it was obscured by the southern tip of Madeline Island

until vessels were almost on top of it. In 1890 the Lighthouse Board

proposed that $7,500 be appropriated to replace the old light with a new

70-foot tall iron tower to be located next to the fog signal building.

Since this new light would be located over a mile from the northwestern

tip of Long Island, it was simultaneously proposed that a small light

and fog bell be constructed on Chequamegon Point at the northwestern tip of the island to

mark the full extremity of the south shore of the passage. Estimating

that this second structure could be built for $2,500, the Board

requested a total appropriation of $10,000 for the full improvements at

Long Island. By the last decade of the nineteenth

century, it became clear that the diminutive 34-foot tall tower of the

LaPointe light was no longer serving the needs of maritime traffic

passing between Madeline, Stockton and Michigan Islands. Located too far

to the west, it was obscured by the southern tip of Madeline Island

until vessels were almost on top of it. In 1890 the Lighthouse Board

proposed that $7,500 be appropriated to replace the old light with a new

70-foot tall iron tower to be located next to the fog signal building.

Since this new light would be located over a mile from the northwestern

tip of Long Island, it was simultaneously proposed that a small light

and fog bell be constructed on Chequamegon Point at the northwestern tip of the island to

mark the full extremity of the south shore of the passage. Estimating

that this second structure could be built for $2,500, the Board

requested a total appropriation of $10,000 for the full improvements at

Long Island.

Since

the LaPointe keepers would soon be responsible for two lights and a fog

signal, it was also determined that a full-time assistant keeper would

need to be assigned to the station to keep up with the workload, and

thus additional living quarters would need to added. In an attempt to

keep costs within the appropriated amount, it was decided to convert the

existing LaPointe lighthouse into a duplex dwelling, since with the

construction of the two new lights the old structure would otherwise no

longer serve any purpose. To this end, the lighthouse tender AMARANTH

delivered a work party to Long Island in the summer of 1896, and the

entire LaPointe lighthouse was jacked-up, and a brick basement

constructed beneath and the interior of the structure reconfigured to

accommodate two keepers. Amazingly, the light atop the roof was kept in

operation throughout the entire reconstruction, and thus the expense of

building a temporary tower was also avoided.

The old lighthouse thus remodeled,

continued to serve as the only dwelling for the Keepers of the new

LaPointe light station until

the construction of a new dwelling close to the new light in 1938 as a Works Progress

Administration project. At this time

a work crew

arrived on the island and built a large modern three-family dwelling

close to the LaPointe Light and fog signal, permitting a more efficient

grouping of the structures which made up the station. The old lighthouse thus remodeled,

continued to serve as the only dwelling for the Keepers of the new

LaPointe light station until

the construction of a new dwelling close to the new light in 1938 as a Works Progress

Administration project. At this time

a work crew

arrived on the island and built a large modern three-family dwelling

close to the LaPointe Light and fog signal, permitting a more efficient

grouping of the structures which made up the station.

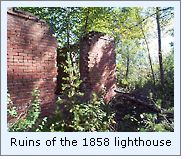

No longer serving

any purpose, the old structure was abandoned, and without continued

maintenance deteriorated quickly. Today, all that remains of the old

LaPointe Lighthouse are the crumbling walls shown in the accompanying

photographs.

Keepers of

this Light

Click here

to see a complete listing of all LaPointe Light keepers compiled by

Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Seeing this Light

For five

days in July, 2002, we were privileged to serve as NPS volunteers,

assisting Park Historian Bob Mackreth in documenting the condition of

all the Apostle Islands Lights, and visited Long Island in a Boston

Whaler on the afternoon of our first day in the Apostles after spending

the morning on Outer Island. Tying the boat to the concrete dock in

front of the station, we first photographed the new tower, dwelling and

oils storage house before setting off for the 3/4 mile trek to the ruins

of the old lighthouse.

It was 95 degrees that

day, and the walk out along the ridge was difficult going since all

remnants of the pathway were overgrown by stubby evergreens. We could

see no evidence remaining of the concrete walks which used to join the

dwelling to the new station, and could not identify whether they had

been removed or were just hidden beneath the island sand and vegetation.

After photographing the

old dwelling, we made our way back to the dock, and spent the next ten

minutes removing ticks from our legs before boarding the Whaler for the

trip back to Bayfield.

Finding this Light

At

this time, the LaPointe Light is the only lighthouse in the Apostles which

is not open to the public on a regular basis. However, the island itself

is open to the public, and with a private boat with which to land on the

island, good views of the exteriors of the new tower, Chequamegon Point

and the ruins of the remodeled dwelling can be obtained.

Contact information

While Apostle

Island Cruise Service offers daily trips around the islands,

passing close to the island for photography, it is only during the two

weeks of the annual Keeper of The Light festival in September that they

offer landings on Long Island. Apostle Island Cruise Services may be

contacted at the following address:

P.O. Box 691 - City

Dock

Bayfield, WI 54814

Telephone: (800) 323-7619

Email: info@apostleisland.com

For information on the Keeper

Of The Light Celebration, contact:

PO Box 990 19 Front St.

Bayfield, WI 54814

Telephone: (800) 779-4487

Historical

references

Annual reports of the lighthouse Board, various, 1853 - 1909 Annual reports of the lighthouse Board, various, 1853 - 1909

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Service, various, 1910 - 1953

Great Lakes Light Lists, various, 1861 - 1977

Annual reports of the Lake Carrier's Association, various, 1906 -

1940

Recent photograph courtesy of Ken & Barb Wardius, Dan Tomhave &

NPS.

Historic photographs courtesy of the NPS Apostle Islands historians offices.

Email correspondence with Bob Mackreth NPS, various, January &

February 2002

Personal observations while on Long Island in July, 2002.

Keeper listings for this light appear

courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|