|

Historical Information

"Big Marsh" is the direct

translation of the French "Grand Marais." While the name was

given by Voyageurs in the early seventeenth century, many subsequent

observers were puzzled, since no marshes have ever been known to exist

here. However, it is believed that the Voyageurs had their own unique

vocabulary, and it is likely that "Marais" referred to a cove,

or harbor of refuge. However, the historical importance trapping to the

area is indisputable, since both the Hudson's Bay Company and John Jacob

Astor's American Fur Company maintained a presence in the area over two

centuries. But it was not until Peter Barbeau established a trading post

on the bay in 1861 that a permanent settlement began to appear.

While the fur trade declined, lumber camps

began to spring up along Superior's south shore, and Grand Marais soon

found itself in the center of a lumbering boom, with stacks of lumber on

its docks awaiting the arrival of vessels to carry the forest's bounty

to the southern lakes.

With

the associated increase in

maritime traffic through the late 1870's, the absence of a safe haven

for mariners coasting the treacherous waters between Whitefish Bay and

Grand Island became a matter of grave concern to maritime interests.

Deducing that the natural harbor could be modified to serve as an

excellent harbor of refuge, the Army Corps of Engineers embarked on an

ambitious harbor improvement project at Grand Marais in 1881. Work

continued over the following ten years, with the construction of a

5,770-foot timber pile breakwater stretching across the bay from

Lonesome Point to a dredged channel at the western shore. Two protective

piers were constructed on each side of the channel, and the protected

harbor area dredged to a depth of 40 feet, allowing access to the

protection of the harbor by the largest vessels of the day. With

the associated increase in

maritime traffic through the late 1870's, the absence of a safe haven

for mariners coasting the treacherous waters between Whitefish Bay and

Grand Island became a matter of grave concern to maritime interests.

Deducing that the natural harbor could be modified to serve as an

excellent harbor of refuge, the Army Corps of Engineers embarked on an

ambitious harbor improvement project at Grand Marais in 1881. Work

continued over the following ten years, with the construction of a

5,770-foot timber pile breakwater stretching across the bay from

Lonesome Point to a dredged channel at the western shore. Two protective

piers were constructed on each side of the channel, and the protected

harbor area dredged to a depth of 40 feet, allowing access to the

protection of the harbor by the largest vessels of the day.

As the forests close to the shore were

lumbered-out, operations moved west where timber could still be

harvested easily, and the Grand Marais mill ceased operations in 1884.

With the closing of the mill, the town's population decreased

dramatically, and turned to fishing to support itself, with Grand Marais

eventually becoming one of Superior's leading bluefin fisheries.

With the Corps of Engineers work on the

harbor of refuge nearing completion in 1892, the Light-House Board

determined that inbound navigation would be improved significantly with

the erection of a light and fog bell on the west pierhead. To this end,

the Board's annual report to Congress of that year included a request

for an appropriation of $15,000 for such a light.

The Manistique Railroad was completed

to Grand Marais in 1893, and with the resultant conduit for transporting

lumber from the virgin forests of interior, the town experienced another

period of rapid growth. The old mill was reactivated, enlarged and

outfitted with the latest equipment, and the harbor was once again

filled with lumber hookers, their decks stacked perilously high to

transport the lumber to feed the insatiable appetite of the rapidly

growing industrialized cities to the south.

The wheels of the government machine

turned typically slowly, and the Congress was not forthcoming with the

requested appropriation for a pierhead light until March 2, 1895.

However, the Board reacted quickly to the appropriation, with plans and

specifications for a skeleton iron tower and elevated walk drawn-up, and

the awarding of contracts for fabrication of the tower's components. The

original estimate of cost included funds for the purchase of a new

fog-bell and striking

mechanism, however with the upgrading of the fog

signal at Point Iroquois from a bell to a steam-whistle being undertaken

that same year, the old Iroquois bell and mechanism was shipped to Grand Marais for

use in the new tower. The wheels of the government machine

turned typically slowly, and the Congress was not forthcoming with the

requested appropriation for a pierhead light until March 2, 1895.

However, the Board reacted quickly to the appropriation, with plans and

specifications for a skeleton iron tower and elevated walk drawn-up, and

the awarding of contracts for fabrication of the tower's components. The

original estimate of cost included funds for the purchase of a new

fog-bell and striking

mechanism, however with the upgrading of the fog

signal at Point Iroquois from a bell to a steam-whistle being undertaken

that same year, the old Iroquois bell and mechanism was shipped to Grand Marais for

use in the new tower.

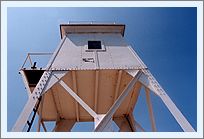

Construction on the pierhead began that

same summer with the bolting of the tower's framework to the pier, and

upon completion in November, the new white painted tower stood

thirty-four feet tall, its octagonal iron lantern housing a sixth-order

fixed white Fresnel lens. Samuel Rodgers was transferred-in as the

station's first keeper, and he exhibited the light for the first time on

the night of December 10. Since no dwelling had been constructed to

accompany the station, Rodgers found himself forced to construct a

temporary shanty on Corps of Engineers property at the inner end of the

west pier.

Perhaps as a result of the cost savings

resulting from the use of the old fog-bell machinery, or perhaps due to

the oversight of not building a keeper's dwelling, the project was

brought-in significantly under budget. Realizing that a second light to

form a rear range for the pierhead light would further improve

navigation into the harbor, the Lighthouse Board requested that the

unexpended portion of the appropriation be applied to the construction

of a rear range light to be located at the inner end of the west pier. Perhaps as a result of the cost savings

resulting from the use of the old fog-bell machinery, or perhaps due to

the oversight of not building a keeper's dwelling, the project was

brought-in significantly under budget. Realizing that a second light to

form a rear range for the pierhead light would further improve

navigation into the harbor, the Lighthouse Board requested that the

unexpended portion of the appropriation be applied to the construction

of a rear range light to be located at the inner end of the west pier.

Congress approved the redirection of

the balance on June 4, 1897, and District Engineer Major Milton B. Adams

awarded the contract for the fabrication of its components on September

27th. The contractor delivered the ironwork at the Detroit depot that

November, however with winter setting-in, work did not begin at site

until June of 1898 when the lighthouse tender Amaranth delivered a work

crew and materials on the pier at Grand Marais.

After the installation of strengthening

timbers at the inner end of the pier to support the additional weight,

the prefabricated tower was erected and painted white to match the

pierhead light. Standing 55 feet in height, its octagonal iron lantern

with a focal plane of fifty-four feet, and the Rodgers exhibited the

lights together for the first time on or about July 15, 1898.

With traffic exploding along the south

shore, the frequency of maritime accidents increased proportionally. To

help guard the safety of mariners, 1898 also saw the beginning of

construction of a life-saving station at the foot of the west pier. On

its completion the following year, the station was considered one of the

finest in all of the Great Lakes, boasting 2 surf boats, a 34-foot

self-righting life boat, and a full complement of beach apparatus.

Doubtless, keeper Rodgers must have felt some resentment, as he watched

this fine new building take shape a few feet from the shanty that had

been his home for the past five years. With traffic exploding along the south

shore, the frequency of maritime accidents increased proportionally. To

help guard the safety of mariners, 1898 also saw the beginning of

construction of a life-saving station at the foot of the west pier. On

its completion the following year, the station was considered one of the

finest in all of the Great Lakes, boasting 2 surf boats, a 34-foot

self-righting life boat, and a full complement of beach apparatus.

Doubtless, keeper Rodgers must have felt some resentment, as he watched

this fine new building take shape a few feet from the shanty that had

been his home for the past five years.

In 1902, the Lighthouse Board finally

acknowledged the dismal conditions under which Rodgers was living, and

requested an appropriation of $5,000 for the construction of a proper

dwelling. The request was repeated for the following two years, however

Congress continued to turn a deaf ear to the request.

The Corps of Engineers continued their

work on the harbor, and as part of the ongoing improvements, the west

pier's length was extended an additional 612 feet in 1904.

The combination of additional work

created by the second light, the dismal conditions under which he had

been living for the past nine years, and no indication that a dwelling

would be built at any time soon may have been more that Rodgers could

stand, since he resigned from lighthouse service on April 5th 1904.

George Barkley officially assumed responsibility for the station the

following day and was likely dismayed to find that he had to take up

residence in Rodgers' old shanty. The combination of additional work

created by the second light, the dismal conditions under which he had

been living for the past nine years, and no indication that a dwelling

would be built at any time soon may have been more that Rodgers could

stand, since he resigned from lighthouse service on April 5th 1904.

George Barkley officially assumed responsibility for the station the

following day and was likely dismayed to find that he had to take up

residence in Rodgers' old shanty.

The following year, the front range

light was unbolted from the pier and moved 550 feet towards the newly

extended pierhead, and additional elevated walkway was installed to

connect the two lights. In concert with this move, the characteristic of

the lights were changed from white to red in order to better distinguish

them from the lights of the town behind the range. Again the Board

requested $5,000 for a dwelling, and again Congress ignored the request. The following year, the front range

light was unbolted from the pier and moved 550 feet towards the newly

extended pierhead, and additional elevated walkway was installed to

connect the two lights. In concert with this move, the characteristic of

the lights were changed from white to red in order to better distinguish

them from the lights of the town behind the range. Again the Board

requested $5,000 for a dwelling, and again Congress ignored the request.

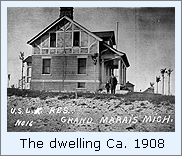

Finally in 1908, Congress responded

with an appropriation of $5,000 to build the keepers dwelling, and a

contract was quickly awarded for the dwelling's construction. Work on

the structure began on June 10th of that same year, and was completed on

September 5, and was a duplicate of the dwelling constructed for the

Munising range lights the previous month. Doubtless, Barkley was happy

to move into the new dwelling, and abandon Rodgers "temporary"

shanty which ended-up serving the Grand Marais keepers for thirteen

years.

Lumbering and commercial fishing waned

on the south shore over the next twenty years, and the number of

commercial vessels entering Grand Marais harbor steadily declined. The

construction of the MacArthur Lock at the Soo in 1943 allowed larger

vessels to enter Lake Superior, and able to stay at sea in foul weather

that would have sent the smaller vessels of the past scurrying for

shelter, Grand Marais harbor became of decreased commercial importance.

The Corps of Engineers stopped maintaining the breakwater during the

1940's, and without constant care the wooden structure quickly rotted

away. Thus unprotected, the harbor began to fill with sand making entry

possible only for smaller vessels. Lumbering and commercial fishing waned

on the south shore over the next twenty years, and the number of

commercial vessels entering Grand Marais harbor steadily declined. The

construction of the MacArthur Lock at the Soo in 1943 allowed larger

vessels to enter Lake Superior, and able to stay at sea in foul weather

that would have sent the smaller vessels of the past scurrying for

shelter, Grand Marais harbor became of decreased commercial importance.

The Corps of Engineers stopped maintaining the breakwater during the

1940's, and without constant care the wooden structure quickly rotted

away. Thus unprotected, the harbor began to fill with sand making entry

possible only for smaller vessels.

Today, the Grand Marais Harbor is

frequented by pleasure craft, and the town is undergoing a resurgence as

it gains popularity as a four-season resort area. Both ranges are still

in place, however the lantern has been removed from the front range, to

be replaced by a modern acrylic lens. The keepers dwelling now serves as

a museum operated by the Grand Marais Historical Society, and is open to

the public from June to September.

Keepers of

this Light

Click here

to see a complete listing of all Grand Marais Range Light keepers

compiled by Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Seeing this Light

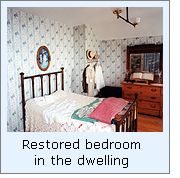

We returned for our third trip to Grand Marais during our July 2002

field trip to find the harbor full of sea kayaks, which were holding

some type of festival that weekend. It was a beautiful day, and we

walked the full length of the pier to obtain close ups of both lights.

Since our previous trips to see these lights had been in September, we

were happy to see the keeper's dwelling museum was open, and we took the

opportunity to tour the beautifully restored building.

Finding this

Light

From the junction of M77 and County Road 702 in downtown Grand Marais,

take CR702 northeast approximately 1/2 mile. The rear range light can be

seen on the right of the road before the road ends in the parking lot of

the old Grand Marais lifesaving station.

The Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore Nautical and Maritime Museum is

located in the lifesaving station, and is well worth a visit. The pier

is a pleasant walk, and both lights are easy to see during good weather.

Reference

Sources

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Board, 1892 - 1908 Annual reports of the Lighthouse Board, 1892 - 1908

Inventory of Historic Light Stations, National Parks Service,

1994

Personal observations and photography at Grand Marais, July 2002.

Photograph courtesy of Brian Malone.

Lake Superior's Shipwreck Coast, Frederick Stonehouse, 1986.

6/21/2001 email from Thomas Tag on the keepers of Grand Marais.

History of the Great Lakes, J.H. Beers Company, 1889

Great Lakes Pilot, First Station on Coast Guard Point, Fern

Erickson, 2000.

Email from Wayne Sapulski, 02/12/02

Lake Superior, Grace Lee Nute, 1944.

Historic postcard courtesy of Cathy Egerer.

Michigan State Archives lighthouse photograph collection.

Grand Marais, Website

Keeper listings for this light appear

courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|