|

Historical Information

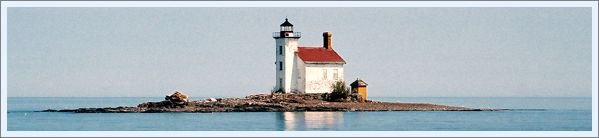

Bete Grise Bay is located on the

south shore of Keweenaw Point, and had long served as a natural harbor

of refuge for vessels seeking to escape the fury of Superior's late

season nor'-westers. Entry into the bay was open to up bound vessels,

however down bound captains were forced to navigate the hazardous two

and a half mile wide passage between the western tip of the point and

Manitou Island before making south into the safety of the bay.

While

the Manitou Light was one of the first tree Lights to be built on

Superior in 1849, its location on the northeast extremity of the island

was designed to serve the regular line of navigation, and did little to

serve vessels making the emergency passage into Bete Grise. To make

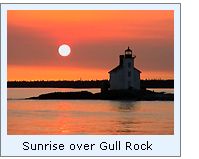

matters worse, a number of shoals and rocky outcroppings peppered the

passage, the most dangerous of which was Gull Rock, located a half mile

off the western shore of Manitou Island. Two hundred and fifty feet in

length and one hundred feet in width, the highest point of Gull Rock

stood less than twelve feet above the water under the calmest

conditions, becoming virtually invisible in the gray darkness of stormy

days when vessels were most likely to be threading their way through the

passage. While

the Manitou Light was one of the first tree Lights to be built on

Superior in 1849, its location on the northeast extremity of the island

was designed to serve the regular line of navigation, and did little to

serve vessels making the emergency passage into Bete Grise. To make

matters worse, a number of shoals and rocky outcroppings peppered the

passage, the most dangerous of which was Gull Rock, located a half mile

off the western shore of Manitou Island. Two hundred and fifty feet in

length and one hundred feet in width, the highest point of Gull Rock

stood less than twelve feet above the water under the calmest

conditions, becoming virtually invisible in the gray darkness of stormy

days when vessels were most likely to be threading their way through the

passage.

Michigan Sixth District Representative

John Fletcher Driggs presented a petition of Michigan citizens praying

for the construction of a lighthouse on Gull Rock before Congress on

January 17, 1865. After consideration and approval by the Lighthouse

Board and the Department of Commerce, Congress approved an appropriation

of $15,000 for the project on July 29 of the following year. Michigan Sixth District Representative

John Fletcher Driggs presented a petition of Michigan citizens praying

for the construction of a lighthouse on Gull Rock before Congress on

January 17, 1865. After consideration and approval by the Lighthouse

Board and the Department of Commerce, Congress approved an appropriation

of $15,000 for the project on July 29 of the following year.

Since Eleventh District construction

crews were already scheduled to be in the vicinity during the 1867

season of navigation for the construction of the identical Lights on Huron

Island and Granite Island,

the district engineer in Detroit determined that the cost of the new

light could be significantly reduced if the same structure design and

construction crew were employed on the Gull Rock construction project.

Work on Gull Rock began at the opening

of the 1867 navigation season, with planned completion by early fall.

However the unfortunate drowning death of construction foreman William

Tunbridge while working on the rock, caused a delay in construction

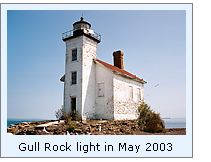

until a new foreman could be selected. Construction began with the

laying of a stone foundation upon which the 1 ½ story, 2,408 square

foot Cream

City brick keepers dwelling slowly took shape. The attached

brick tower contained a spiral iron staircase, which served both

dwelling floors as well as providing access to the lantern. The tower

was capped with a prefabricated octagonal cast iron lantern, with its

ventilator ball standing 46 feet above the building's foundation. The

lantern was equipped with a fixed red Fourth

Order Fresnel lens. With a focal plane of 50 feet, it was

calculated that the light would be visible for a distance of 13 ¼ miles

in clear weather. A brick privy, a boat landing and a series of

connecting concrete sidewalks completed the sparse station's complement

of structures. Thomas Jackson was appointed as Gull Rock's first keeper,

and after arriving at the station he exhibited the light for the first

time on the night of November 1, 1867. Work on Gull Rock began at the opening

of the 1867 navigation season, with planned completion by early fall.

However the unfortunate drowning death of construction foreman William

Tunbridge while working on the rock, caused a delay in construction

until a new foreman could be selected. Construction began with the

laying of a stone foundation upon which the 1 ½ story, 2,408 square

foot Cream

City brick keepers dwelling slowly took shape. The attached

brick tower contained a spiral iron staircase, which served both

dwelling floors as well as providing access to the lantern. The tower

was capped with a prefabricated octagonal cast iron lantern, with its

ventilator ball standing 46 feet above the building's foundation. The

lantern was equipped with a fixed red Fourth

Order Fresnel lens. With a focal plane of 50 feet, it was

calculated that the light would be visible for a distance of 13 ¼ miles

in clear weather. A brick privy, a boat landing and a series of

connecting concrete sidewalks completed the sparse station's complement

of structures. Thomas Jackson was appointed as Gull Rock's first keeper,

and after arriving at the station he exhibited the light for the first

time on the night of November 1, 1867.

With

the primitive living conditions and the limited space

afforded by life on the rock, Gull Island

was considered one of the most isolated and difficult stations on the

Great Lakes. With no fog signal to tend there was little to do beyond

the mandatory morning lens, lantern and lamp maintenance. While there

was barely sufficient work to keep one man busy, both a keeper and

assistant were assigned to the station, likely more to provide

companionship than to share the workload. Even so, the turnover rate for assistant

keepers was abnormally high. To ease the situation, the district

inspectors approved the appointment of a number of keepers wives to the

position of assistant over the years. In this manner, Keeper James

Corgan's wife Mary served as his assistant for all six years during

which Corgan was keeper at The Rock from 1877 through 1883. With

the primitive living conditions and the limited space

afforded by life on the rock, Gull Island

was considered one of the most isolated and difficult stations on the

Great Lakes. With no fog signal to tend there was little to do beyond

the mandatory morning lens, lantern and lamp maintenance. While there

was barely sufficient work to keep one man busy, both a keeper and

assistant were assigned to the station, likely more to provide

companionship than to share the workload. Even so, the turnover rate for assistant

keepers was abnormally high. To ease the situation, the district

inspectors approved the appointment of a number of keepers wives to the

position of assistant over the years. In this manner, Keeper James

Corgan's wife Mary served as his assistant for all six years during

which Corgan was keeper at The Rock from 1877 through 1883.

According to the logbook entries of

John Nolan who served as Keeper from April 1897 to May 1903, water

in the passage usually began to ice over around the first week in

December each year, and the Light was extinguished for the winter, and

Nolan gingerly made his way to winter quarters in Copper

Harbor. As the ice began to break toward the end of April, he

returned to take up residence in the station. Although the entire

building was cold and damp, and the illuminating apparatus dirty, Nolan

reported that he usually managed to have the light illuminated on the

same day as his return to the station.

By virtue of its exposed location, one

would assume that the Gull Rock Light would have required constant

maintenance. However, Lighthouse Board annual reports on work performed

at the station would indicate otherwise, with few major repairs reported

over the entire active life of the station. By virtue of its exposed location, one

would assume that the Gull Rock Light would have required constant

maintenance. However, Lighthouse Board annual reports on work performed

at the station would indicate otherwise, with few major repairs reported

over the entire active life of the station.

After successful installation of fog

signal plants at Marquette

Harbor, Skillagallee,

South Manitou,

Outer Island and Huron

Island, in 1873 the Lighthouse Board requested an

appropriation for the construction of such a plant at Gull Rock, however

the station was never so equipped. 1883 saw the replacement of the

station's concrete walkways, and a 29 foot long boat landing was

constructed on the south side of the rock in 1890, along with various

minor repairs.

Superior has always been famous for its

violent November storms, and 1892 was no exception, when on November 7th

the Canadian 3-masted schooner barge G M NEELON broke away from the tow

of the steamer S L TILLEY and struck the rock in heavy seas. While the

vessel was abandoned and considered to be a total loss, she was

recovered by the wrecker J H GILLETT a year later, and after repairs was

placed back into service. Superior has always been famous for its

violent November storms, and 1892 was no exception, when on November 7th

the Canadian 3-masted schooner barge G M NEELON broke away from the tow

of the steamer S L TILLEY and struck the rock in heavy seas. While the

vessel was abandoned and considered to be a total loss, she was

recovered by the wrecker J H GILLETT a year later, and after repairs was

placed back into service.

The lighthouse tender AMARANTH

delivered the materials and a work crow to construct an oil storage

building in 1896, and two years later a work crew arrived to reconstruct

the boat landing which had been damaged by ice. In his log for October

12th of 1898 keeper Nolan recorded that "the men could not work at

the boat ways today, as the sea was coming up to the boat house door and

spray was flying across the rock." That same year, eighteen

improved Fourth Order lamps were delivered at the Detroit depot, one of

which was installed at Gull Rock. The lighthouse tender AMARANTH

delivered the materials and a work crow to construct an oil storage

building in 1896, and two years later a work crew arrived to reconstruct

the boat landing which had been damaged by ice. In his log for October

12th of 1898 keeper Nolan recorded that "the men could not work at

the boat ways today, as the sea was coming up to the boat house door and

spray was flying across the rock." That same year, eighteen

improved Fourth Order lamps were delivered at the Detroit depot, one of

which was installed at Gull Rock.

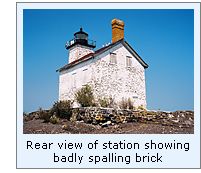

As a result of frequent pounding by the

waves, a 40 foot long retaining wall of

rubble masonry at the northeast corner of the dwelling in 1901, with a coping of

Portland cement added to ensure durability and effectiveness as a

barrier to water penetration. The boat landing was once again rebuilt,

and a sixty foot stone filled protecting crib constructed to help keep

ice away from the landing. As a result of frequent pounding by the

waves, a 40 foot long retaining wall of

rubble masonry at the northeast corner of the dwelling in 1901, with a coping of

Portland cement added to ensure durability and effectiveness as a

barrier to water penetration. The boat landing was once again rebuilt,

and a sixty foot stone filled protecting crib constructed to help keep

ice away from the landing.

September 16, 1912 saw the second wreck

on Gull Rock. In an attempt to escape a real gut-buster of a storm on

the big, the 312 foot steel bulk freighter Spokane drove straight onto

the rock and broke clean in two. As was the case with the Neelon ten

years previous, while the Spokane was declared a total loss, she was

subsequently recovered and rebuilt, and continued to ply the lakes for

23 years until she was scrapped in 1935.

1913 was a particularly eventful year

at Gull Rock. On June 25th an acetylene illumination system was

installed in the fourth order lens. Equipped with a sun valve, the lamp

was automatically turned on at dusk and extinguished after dawn. At this

time the characteristic of the light was also changed from fixed red to

flashing red every 3 seconds and the intensity increased from 130 to 180

candlepower. The installation of a large acetylene tank allowed the

light to operate untended for long periods of time. With a resident

keeper no longer necessary to tend the light, management of the Gull

Rock light was turned over to the keepers of the Manitou Light, and Gull

Rock was secured and largely abandoned. 1913 was a particularly eventful year

at Gull Rock. On June 25th an acetylene illumination system was

installed in the fourth order lens. Equipped with a sun valve, the lamp

was automatically turned on at dusk and extinguished after dawn. At this

time the characteristic of the light was also changed from fixed red to

flashing red every 3 seconds and the intensity increased from 130 to 180

candlepower. The installation of a large acetylene tank allowed the

light to operate untended for long periods of time. With a resident

keeper no longer necessary to tend the light, management of the Gull

Rock light was turned over to the keepers of the Manitou Light, and Gull

Rock was secured and largely abandoned.

On November 8th, the 450 foot steel

hulled bulk freighter L C WALDO, fully loaded with iron ore was driven

ashore by a huge gale, ending up on Gull Rock. The Copper Harbor

lifesavers struggled heroically for four days to successfully rescue all

of her crew members. While she too was quickly declared a total loss,

she was later removed and rebuilt, and was sold into Canadian ownership.

The vessel subsequently moved into international trade, and ended up

sinking near Portofino, Italy while being towed to a scrap yard in

LaSpezia. On November 8th, the 450 foot steel

hulled bulk freighter L C WALDO, fully loaded with iron ore was driven

ashore by a huge gale, ending up on Gull Rock. The Copper Harbor

lifesavers struggled heroically for four days to successfully rescue all

of her crew members. While she too was quickly declared a total loss,

she was later removed and rebuilt, and was sold into Canadian ownership.

The vessel subsequently moved into international trade, and ended up

sinking near Portofino, Italy while being towed to a scrap yard in

LaSpezia.

Today, the Gull Rock Light still

guides mariners through the passage, its illumination provided by a

solar powered 12 volt DC 250 mm acrylic

optic. At some time the Fourth

Order lens was removed from the lantern and while it is reportedly on

display at the Whitefish

Point Light Station, recent evidence indicates that the lens

displayed lens in the museum came from the old iron skeleton tower which

was located on Gull Island to the west of the Beaver archipelago in Lake

Michigan.

The lighthouse was excessed through the National

Lighthouse Preservation Act in 2002, and in 2004 an individual who owns

property in the area partnered with the Michigan Lighthouse Foundation

to form

Gull Rock

Lightkeepers to apply for ownership of the station. The group

received ownership of the station in in June 2005, and is undertaking

the arduous task of stabilizing and restoring the station to serve

as a retreat for writers and artists.

Keepers of

this Light

Click here

to see a complete listing of all Gull Rock Light keepers compiled by

Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Seeing this Light

Sand Point Charters out of La La Belle offers lighthouse cruises by

Mendota, Gull Rock and Manitou Island. For more information visit their website,

or telephone Sand Point Charters at (906) 370-2257.

Contact Information

Gull Rock Lightkeepers

Website:

www.gullrocklightkeepers.org

Email:

info@gullrocklightkeepers.org

Reference Sources

Congressional Record, 1865

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Board, various 1867 to 1903

Annual reports of the Lake Carriers Association, various 1903 to 1927

Lighthouse Digest, August 1999 & July 2000.

Gull Rock station log for 1883

The Great Lakes Shipwreck database, Dave Swayze.

August 2000 photograph courtesy of Alex Protzel

Keeper listings for this light appear

courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|