|

Historical Information

With the discovery of copper in the Keweenaw, immigrant Cornish and

Finnish miners began flocking to the area to seek their fortunes and in

the words of one pioneer "the shores of the Keweenaw became

whitened with tents." Copper Harbor's natural harbor quickly

assumed significance as a supply point for the miners, and with the

influx of mining traffic the Federal Government established a Mineral

Land Agency office in the harbor to better regulate the growing mining

industry.

While Copper Harbor was both expansive

and well protected, vessels entering the harbor were forced to find

their way through a relatively narrow rocky opening. While great caution

had to be exercised during optimum conditions, finding the natural

harbor opening at night or during thick weather was a virtual

impossibility. The maritime community began raising its voice to

complain of the situation at Copper Harbor, and under the recommendation

of Stephen Pleasonton who was responsible for the nation's lighthouses

at the time, and on March 3, 1847 Congress appropriated $5,000 for the

construction of a light at the harbor entrance. While Copper Harbor was both expansive

and well protected, vessels entering the harbor were forced to find

their way through a relatively narrow rocky opening. While great caution

had to be exercised during optimum conditions, finding the natural

harbor opening at night or during thick weather was a virtual

impossibility. The maritime community began raising its voice to

complain of the situation at Copper Harbor, and under the recommendation

of Stephen Pleasonton who was responsible for the nation's lighthouses

at the time, and on March 3, 1847 Congress appropriated $5,000 for the

construction of a light at the harbor entrance.

The new station was erected on the

rocky point to the east of the harbor opening by contractor Charles

Rude, and consisted of a 48-foot tall rubble stone tower, which tapered

from thirty feet in diameter at the base to 20 feet in diameter at the

uppermost level. Capped with an octagonal lantern with a domed copper

roof similar to that which can still be seen at Rock Harbor, a

chandelier supporting an array of 13 Argand lamps with reflectors was

erected within. By virtue of the tower's construction atop the elevated

central ridge of the rocky peninsula, the lights sat at a focal plane of

65 feet. However, as a result of their inefficiency of the Argand lamps,

the new Copper Harbor light was only visible for a distance of four

miles in clear weather conditions.

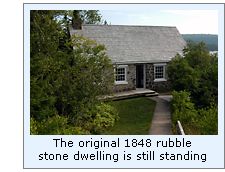

A 1½-story rubble stone dwelling was

located on the harbor side of the rocky point close to the water's edge.

The diminutive dwelling featured two rooms and a hallway on the first

floor, two bedrooms on the second floor, and a small kitchen in a

lean-to at the rear. While land access to the lighthouse was available

around the eastern end of the harbor, water access to the growing

village was faster, and a timber dock for the keepers boat was erected

at the water's edge near the dwelling. Construction of the station was

completed in 1848, however with the station's first keeper yet to be

appointed, Charles Rude was forced to leave a watchman to tend the

station until through the end of the navigation season. Henry Clow was

finally appointed to the position of keeper of the Copper Harbor Light,

and he arrived at the station on February 34, 1849, and took residence

in the new dwelling along with his wife and two children. A 1½-story rubble stone dwelling was

located on the harbor side of the rocky point close to the water's edge.

The diminutive dwelling featured two rooms and a hallway on the first

floor, two bedrooms on the second floor, and a small kitchen in a

lean-to at the rear. While land access to the lighthouse was available

around the eastern end of the harbor, water access to the growing

village was faster, and a timber dock for the keepers boat was erected

at the water's edge near the dwelling. Construction of the station was

completed in 1848, however with the station's first keeper yet to be

appointed, Charles Rude was forced to leave a watchman to tend the

station until through the end of the navigation season. Henry Clow was

finally appointed to the position of keeper of the Copper Harbor Light,

and he arrived at the station on February 34, 1849, and took residence

in the new dwelling along with his wife and two children.

By the early 1850's a cry arose in the

maritime community, voicing concern over Pleasonton's tight-fisted

administration of the nation's aids to navigation. A clerical

administrator, Pleasonton had no maritime experience, and it showed-up

in the sub standard workmanship and poorly chosen locations of many of

the lighthouses erected under his administration. A study commissioned

by Congress recommended the establishment of a nine-member Board to

oversee the administration of aids to navigation. Staffed with Navy

officers and Engineers from the Army Corps of Engineers, the Lighthouse

Board was established in 1852, relieving Pleasonton from any further

involvement. One of the Board's first orders of priority was the

upgrading of illumination systems from the dim and poorly performing

Argand lamps to the far more efficient and powerful Fresnel lenses

manufactured in Paris. However, with the Copper Harbor Light not being

of major importance in the greater scheme of things, it would be some

time before its lens would be upgraded, and thus the Argand lamps

continued to light the way into the harbor.

The lighthouse keeper's life was

evidently not to Clow's liking, as he resigned from his position on

August 5 1853, to be replaced by Henry C Shurter. Evidently Shurter was

not much better suited to the keeper's life, as he was removed from the

position and replaced by Napoleon Beedon on March 32, 1855. The lighthouse keeper's life was

evidently not to Clow's liking, as he resigned from his position on

August 5 1853, to be replaced by Henry C Shurter. Evidently Shurter was

not much better suited to the keeper's life, as he was removed from the

position and replaced by Napoleon Beedon on March 32, 1855.

In 1856, a work crew finally arrived in

at the station and removed the Argand lamps from the lantern, and

replaced them with a single fixed white Sixth Order Fresnel lens, thus

increasing the station's range of visibility to ten miles at sea. Three

years later, the Light was upgraded further through the replacement of

the Sixth Order lens with a more powerful fixed white lens of the Fourth

Order.

As was the case with virtually all of

the lighthouses built on the Great Lakes during the Pleasonton

administration, the true costs of inferior materials and shoddy

workmanship began to show. After his 1864 visit to the station, the

Eleventh District Inspector remarked that the Copper Harbor lighthouse

required "extensive repairs." On subsequent investigation, the

condition of the tower was determined to be beyond repair, and the

following year the decision was made to raze the old tower and erect a

completely new structure. With old Pleasonton-era stations needing

replacement at both Marquette and Ontonagon, and new stations planned

for Gull Rock, Huron and Granite Islands, the decision was made to build

all six lights to the same plan. Specifying a simple brick two-story

dwelling with a tower integrated into the center of one of the gable end

walls, this design would eventually become known as the

"schoolhouse" style, as a result of its similarity to the

design of rural nineteenth century one room schoolhouses.

The lighthouse tender HAZE returned to

Copper Harbor in early 1866 and deposited a working crew and materials

on lighthouse point to begin construction of the new main lighthouse.

Work began with the demolishing of the old rubble stone tower, and

excavating the foundation for the new structure. Under normal

circumstances one would assume that the old tower would have been left

standing until the new station was complete. However, an archeological

survey conducted by the Michigan Technological University in 1994 showed

that a large portion of the stone from the old tower was reused in

building the foundation of the new building. Thus it is evident that the

old tower must have been demolished first. What steps were put in place

to allow the continued display of a light at the station for the time

period between the demolishing of the old tower and the completion of

the new structure are unrecorded. However, it is almost certain that

some arrangement for the display of a temporary light would have been

made. The lighthouse tender HAZE returned to

Copper Harbor in early 1866 and deposited a working crew and materials

on lighthouse point to begin construction of the new main lighthouse.

Work began with the demolishing of the old rubble stone tower, and

excavating the foundation for the new structure. Under normal

circumstances one would assume that the old tower would have been left

standing until the new station was complete. However, an archeological

survey conducted by the Michigan Technological University in 1994 showed

that a large portion of the stone from the old tower was reused in

building the foundation of the new building. Thus it is evident that the

old tower must have been demolished first. What steps were put in place

to allow the continued display of a light at the station for the time

period between the demolishing of the old tower and the completion of

the new structure are unrecorded. However, it is almost certain that

some arrangement for the display of a temporary light would have been

made.

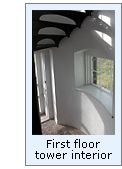

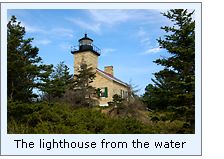

Atop the rubble stone foundation, a

team of masons erected a Cream City brick building, and its 42-foot tall

tower capped with a square gallery with iron safety railing. A spiral

cast iron stairway within the tower provided the only means of passing

between the first and second floors in addition to providing access to

the lantern. Centered atop the gallery, a decagonal prefabricated cast

iron lantern was installed, and the Fourth Order lens from the old tower

reassembled atop a cast iron pedestal at the center of the new lantern.

Two years later in 1868, the Eleventh

District Inspector reported that he found everything at the station to

be in "good condition," with the exception of the water

cistern, which was found to be leaking, which was repaired the following

year. However, 1869 is more memorable as the year in which Napoleon

Beedon resigned from lighthouse service after fourteen years as keeper

of the Copper Harbor Light. John Power was selected to replace Beedon,

arriving to take over the Light on September 1. As yet, we have been

unable to determine the reason behind Napoleon Beedon's resignation.

However, it is interesting to note that after fourteen years at Copper

Harbor, lighthouse keeping was evidently in Beedon blood, as he would

subsequently reenter lighthouse service and serve as keeper at Grand

Island Harbor and at Au Sable Point before resigning a second time in

1879. Two years later in 1868, the Eleventh

District Inspector reported that he found everything at the station to

be in "good condition," with the exception of the water

cistern, which was found to be leaking, which was repaired the following

year. However, 1869 is more memorable as the year in which Napoleon

Beedon resigned from lighthouse service after fourteen years as keeper

of the Copper Harbor Light. John Power was selected to replace Beedon,

arriving to take over the Light on September 1. As yet, we have been

unable to determine the reason behind Napoleon Beedon's resignation.

However, it is interesting to note that after fourteen years at Copper

Harbor, lighthouse keeping was evidently in Beedon blood, as he would

subsequently reenter lighthouse service and serve as keeper at Grand

Island Harbor and at Au Sable Point before resigning a second time in

1879.

By the 1880's, the mines in the eastern

tip of the Keweenaw had all but closed, and with opening of the Portage

Lake Ship Canal, many vessels were using the short cut it represented.

Thus, the volume of maritime traffic both entering and passing Copper

Harbor diminished. Ever watchful for an opportunity to reduce costs, the

Lighthouse Board determined that two lights in the harbor were overkill.

Since the range lights could be seen from outside the harbor, the Board

decided that they could perform double duty as both range and as a coast

lights, and decided to shut down the main light and eliminate the cost

of operating the light. Thus, in 1884 the main light was extinguished,

and the keeper of the Range Lights put in charge of the building and

grounds. By the 1880's, the mines in the eastern

tip of the Keweenaw had all but closed, and with opening of the Portage

Lake Ship Canal, many vessels were using the short cut it represented.

Thus, the volume of maritime traffic both entering and passing Copper

Harbor diminished. Ever watchful for an opportunity to reduce costs, the

Lighthouse Board determined that two lights in the harbor were overkill.

Since the range lights could be seen from outside the harbor, the Board

decided that they could perform double duty as both range and as a coast

lights, and decided to shut down the main light and eliminate the cost

of operating the light. Thus, in 1884 the main light was extinguished,

and the keeper of the Range Lights put in charge of the building and

grounds.

Maritime interests quickly raised their

voices to make the Board aware of the folly of the decision to close the

Copper Harbor Light. Located deep within Copper Harbor as they were, the

range lights were invisible until vessels were in front of the harbor

entrance. After passing the Manitou and Gull Rock Lights, up-bound

mariners now found themselves coasting blind along the treacherous

Keweenaw shoreline until they were able to pick up the Eagle Harbor

Light. After a number of protests were registered, the Lighthouse Board

realized the errors of the decision, and ordered the reactivation of the

Copper Harbor main light on February 17, 1888. A work crew arrived to

prepare the station for reactivation that May, and with the arrival of

Mr. Crump, the District Lampist, on May 22, work began on the

installation of a new Fourth Order lens in the empty lantern.

Henry Corgan, who had lived for some

time at the Copper Harbor Light while his father Charles was Keeper from

1873 through 1881, had followed in his father's footsteps, entering

lighthouse service in 1868 as First Assistant at Manitou. While later

serving as keeper at Point Peninsula, Corgan learned of the Board's

plans to reactivate the Copper Harbor Light, and evidently having fond

memories of the place, managed to convince District Inspector Commander

Horace Elmer to reassign him as keeper at his father's old station. Henry Corgan, who had lived for some

time at the Copper Harbor Light while his father Charles was Keeper from

1873 through 1881, had followed in his father's footsteps, entering

lighthouse service in 1868 as First Assistant at Manitou. While later

serving as keeper at Point Peninsula, Corgan learned of the Board's

plans to reactivate the Copper Harbor Light, and evidently having fond

memories of the place, managed to convince District Inspector Commander

Horace Elmer to reassign him as keeper at his father's old station.

With the renovation work close to

completion, the light was reactivated on the night of June 1, 1888, and

was tended by the work crew for five days until Henry Corgan arrived to

take over the station on June 6.

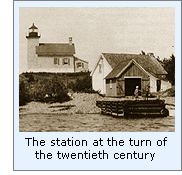

Things were relatively uneventful at

Copper Harbor over the next thirty years, with Corgan serving as the

single keeper throughout the entire period. Little mention of the

station is made in official government documents until 1893, when it was

mentioned that Corgan built a small boathouse and a work crew arrived to

lay 200 feet of sidewalk connecting the new boathouse to the lighthouse.

Two years later, a new boat landing was erected, and a barbed-wire fence

installed across the point to keep visitors off the property. 1907 saw

the arrival of a crew to upgrade Corgan's diminutive boathouse with a

more substantial structure and to erect a new stone-filled timber boat

landing.

After the abolishment of the Lighthouse

Board in 1909, and the transfer of responsibility for the nation's to

the newly formed Lighthouse Service under the direction of George

Putnam, major strides were taken to incorporate new technology

throughout the system. With recent advances in acetylene lighting

technology, and the reliable sun valve which could be used to

automatically illuminate and extinguish the light at dusk and dawn, a

move was on to automate a number of the nation's lighthouses, thereby

eliminating the cost of keepers at the stations. To this end, an

acetylene illumination system was installed within the Copper Harbor

Fourth Order Fresnel lens on June 23, 1919, and the light's

characteristic simultaneously changed to a white flash of 0.3-second

duration followed by a 2.7-second eclipse. Emitting 750 candlepower, the

new light was now visible from a distance of 15 miles at sea. No longer

needed to tend the light, the 66-year old Corgan accepted a transfer to

the St. Clair Flats South Ship Canal Light, leaving Copper Harbor for

good. After the abolishment of the Lighthouse

Board in 1909, and the transfer of responsibility for the nation's to

the newly formed Lighthouse Service under the direction of George

Putnam, major strides were taken to incorporate new technology

throughout the system. With recent advances in acetylene lighting

technology, and the reliable sun valve which could be used to

automatically illuminate and extinguish the light at dusk and dawn, a

move was on to automate a number of the nation's lighthouses, thereby

eliminating the cost of keepers at the stations. To this end, an

acetylene illumination system was installed within the Copper Harbor

Fourth Order Fresnel lens on June 23, 1919, and the light's

characteristic simultaneously changed to a white flash of 0.3-second

duration followed by a 2.7-second eclipse. Emitting 750 candlepower, the

new light was now visible from a distance of 15 miles at sea. No longer

needed to tend the light, the 66-year old Corgan accepted a transfer to

the St. Clair Flats South Ship Canal Light, leaving Copper Harbor for

good.

Only needing access to the tower to

service the lens and acetylene system, the Lighthouse Service began

leasing the lighthouse dwelling to private individuals as a summer

cottage in 1927. With the tower stairs serving double duty as the only

access to the second floor of the dwelling and to the lantern, it was

difficult to maintain privacy for the tenants when crews arrived at the

station to maintain the light. Thus, in 1933, the decision was made to

erect a 62-foot high steel skeleton tower close to the site of the

original 1848 tower. The Fresnel lens in the old lantern was a delicate

assembly, and not intended to be installed in a location where it would

be directly exposed to the elements. The Fourth Order lens was thus

disassembled and shipped to the Detroit depot for storage, and the new

steel tower capped with a 300-mm lens, which was plumbed into the

acetylene system, which had been relocated from the old tower. Only needing access to the tower to

service the lens and acetylene system, the Lighthouse Service began

leasing the lighthouse dwelling to private individuals as a summer

cottage in 1927. With the tower stairs serving double duty as the only

access to the second floor of the dwelling and to the lantern, it was

difficult to maintain privacy for the tenants when crews arrived at the

station to maintain the light. Thus, in 1933, the decision was made to

erect a 62-foot high steel skeleton tower close to the site of the

original 1848 tower. The Fresnel lens in the old lantern was a delicate

assembly, and not intended to be installed in a location where it would

be directly exposed to the elements. The Fourth Order lens was thus

disassembled and shipped to the Detroit depot for storage, and the new

steel tower capped with a 300-mm lens, which was plumbed into the

acetylene system, which had been relocated from the old tower.

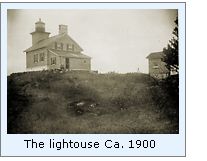

The Coast Guard, which had assumed

responsibility for the nation's aids to navigation in 1939, decided that

it no longer wished to serve as landlord at Copper Harbor, and placed

the building and reservation up for sale in 1957. The State of Michigan

purchased the buildings for $5,000, and incorporated them into the Fort

Wilkins State Park. Restoration efforts began in the early 1970's, and

the buildings were eventually opened-up as a museum in 1975. The main

lighthouse has been restored to reflect its appearance at the turn of

the twentieth century, and the original keepers dwelling has been

converted into a museum, with exhibits showing aspects of daily life at

the station.

Keepers of this

Light

Click here

to see a complete listing of all Copper Harbor Light keepers compiled by

Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Seeing this Light

Take US41 into Copper Harbor, and continue North through the village.

You will find Fort Wilkins State Park on the right, and a parking area

on the left. Park your vehicle in the parking area and walk to the

lakeshore. The lighthouse can be seen across the bay.

For the best view of

the light station, the Copper Harbor Lighthouse Ferry Service is the

only way to go. Their boat leaves the municipal dock three times a day

for an enjoyable 15-minute cruise across Copper Harbor, and ties up at

the same dock used by the keepers many years ago.

After arriving at the

dock, you join a Michigan Department of History staff member who

provides an informative and comprehensive tour of the entire light

station complex.

For more information on

tour schedules and fees, click here

to visit the Copper Harbor Lighthouse website, or telephone (906)

289-4966 for information.

Contact information

Fort Wilkins State Park

East US-41

Copper Harbor, MI 49918

(906) 289-4215

Reference Sources

Annual reports of the Fifth Auditor of the

Treasury 1848 & 1849

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Board. Various - 1856 through

1907

Annual report of the Lake Carriers Association, Various - 1919

through 1937

Great Lakes Light Lists – Various - 1849 through 2004

1858 & 1910 surveys of the Copper Harbor Lighthouse. USCG CD

database

History & Archaeology of the First Copper Harbor Lighthouse.

Barry James & Grant Day. 1995.

Copper Harbor Light Station, Mich. Plan showing location of

original drawings. NARA RHL 704-679

History of the Great Lakes. Volume I . J. B. Mansfield. 1889

Adventures in the wilds of the United States and British American

provinces." Charles Lanman. 1856.

The metallic wealth of the United States" Josiah Dwight Whitney. Pub.

1856.

Lake Superior. Grace Lee Nute. 1944

Copper Harbor lighthouse – Michigan Department of Arts, Histories

and Libraries website

Information contained on interpretive displays at the Copper Harbor

lighthouse itself.

Keeper listings for this light appear

courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|