|

Historical Information

Edward Taylor was the first to realize the

commercial potential of Eagle Harbor, building a short timber pier in

the bay in 1844 from which to supply the growing number of miners in the

area. A rocky ledge with only eight feet of water above it spread across

the harbor entry, and represented a barrier to vessels of deep draft.

However, the copper boom saw an increasing number of vessels visiting

the dock, and Taylor began to lobby for federal funding for improving

the entry into the harbor.

At the time, responsibility for the nation’s navigational aids at

the time fell under Stephen Pleasonton, the Fifth Auditor of the

Treasury. Pleasonton’s experience was purely in the area of fiscal

administration, and having no background in maritime matters, his

administration was characterized by slow reaction to maritime need and

the choice of "least cost" alternatives. However, convinced of

the need to establish a Light at Eagle Harbor, Pleasonton convinced

Congress to pass an appropriation of $4,000 for the construction of a

Light to guide mariners into Eagle Harbor on March 3, 1849. At the time, responsibility for the nation’s navigational aids at

the time fell under Stephen Pleasonton, the Fifth Auditor of the

Treasury. Pleasonton’s experience was purely in the area of fiscal

administration, and having no background in maritime matters, his

administration was characterized by slow reaction to maritime need and

the choice of "least cost" alternatives. However, convinced of

the need to establish a Light at Eagle Harbor, Pleasonton convinced

Congress to pass an appropriation of $4,000 for the construction of a

Light to guide mariners into Eagle Harbor on March 3, 1849.

Construction began on the western point of Eagle Harbor in 1850, and

while we have yet to find exact specifications for the structure, we do

know that the structure took the form of a rubble stone keeper’s

dwelling with a square white-painted wooden tower integrated into one

end of the roof. The tower was capped with an octagonal wooden lantern

with multiple glass panes, and outfitted with an array of Lewis lamps

with reflectors. With the lamps standing 21 feet above the dwelling’s

foundation, the building’s location on high ground placed the lamps at

a focal plane of 47 feet above lake level. John Griswold was appointed

as the station’s first Keeper, and while he first appears in payroll

records for the station on October 25, 1850, subsequent reports indicate

that the new station was not exhibited until 1851. Thus, it is likely

that construction was not completed before winter’s grip spread across

Superior, and exhibition of the light was thus delayed until the opening

of the 1851 navigation season.

Through the early 1850's a cry arose in the maritime community,

voicing concern over Pleasonton's tight-fisted administration. A study

commissioned by Congress concurred with the concern, and recommended the

establishment of a nine-member Board to oversee the administration of

aids to navigation. Staffed with Scientists, Navy officers and Engineers

from the Army Corps of Engineers, the Lighthouse Board was established

in 1852, and Pleasonton relieved from any further involvement with aids

to navigation. One of the Board's first orders of priority was the

upgrading of illumination systems from the dim and poorly performing

Lewis Lamps to the far more efficient and powerful French Fresnel

lenses. To this end, the Lewis lamps were removed from the lantern at

Eagle Harbor in 1857, and replaced with a Fourth Order Fresnel lens,

exhibiting a characteristic fixed white light varied by a white flash

every two minutes. Through the early 1850's a cry arose in the maritime community,

voicing concern over Pleasonton's tight-fisted administration. A study

commissioned by Congress concurred with the concern, and recommended the

establishment of a nine-member Board to oversee the administration of

aids to navigation. Staffed with Scientists, Navy officers and Engineers

from the Army Corps of Engineers, the Lighthouse Board was established

in 1852, and Pleasonton relieved from any further involvement with aids

to navigation. One of the Board's first orders of priority was the

upgrading of illumination systems from the dim and poorly performing

Lewis Lamps to the far more efficient and powerful French Fresnel

lenses. To this end, the Lewis lamps were removed from the lantern at

Eagle Harbor in 1857, and replaced with a Fourth Order Fresnel lens,

exhibiting a characteristic fixed white light varied by a white flash

every two minutes.

With the establishment of a new light station at Eagle River in 1859,

John Griswold accepted a transfer to the new station, and with his

departure John Alexander took over the station on February 1, 1859. By

1865, a total of four new Keepers had worked at the station, with two of

them removed from office, one resigning, and one passing away after only

seven months at the station. Civil War veteran Peter C Bird was

appointed as Keeper on August 12, 1865. Bird had suffered a severe leg

injury at the battle of Gettysburg, and appears to have been a

relatively common practice for partially disabled veterans to be

rewarded for their service with appointment to keeper positions.

A short seventeen years after its construction, an 1868 inspection of

the station found the building to be in critically deteriorating

condition. Finding the rubble stone to be "laid together in the

rudest manner" and its lantern "of the oldest pattern having

small panes of glass, and heavy sash bars which obstruct the light," the Lighthouse Board recommended an appropriation of

$14,000 to allow a complete rebuilding of the station. Congress

responding with the requested appropriation on July 15, 1870, and later

that year contracts were awarded for supplying the building materials

and iron work needed for the construction of the new station. With the

delivery of a work crew and materials at Eagle Harbor on the opening of

the 1871 navigation season, construction of the new station began in

earnest.

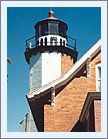

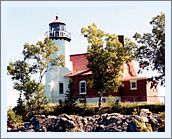

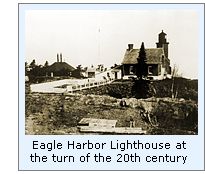

Rather than creating a unique set of plans for the new station,

Eleventh District Engineer Brevet Brigadier General Orlando M. Poe

resurrected a plan which had been previously used on Chambers Island in

1867 and at Eagle Bluff in 1868. After blasting out a hole for the

cellar, the masons crafted a two-story dwelling red brick dwelling,

29-foot by 25-foot in plan, with an integrated 44-foot tall tower

oriented diagonally into its northeastern corner. The exterior of the

first and second stories of the tower were approximately ten feet square

with buttressed corners, while the tower's upper portion consisted of a

ten-foot octagon. The tower was double-walled, with a circular inner

wall approximately four inches thick and eight feet in diameter. This

cylindrical inner wall supported a cast iron spiral staircase which

wound from the oil storage room in the cellar to a hatch in the lantern

floor. Since these spiral stairs also served as the only means of moving

between floors in the dwelling, steel doors provided access to landings

on both the first and second floors to prevent the spread of any fire in

either the dwelling or tower. The first floor of the dwelling contained

a parlor, kitchen and two bedrooms, and the second floor two bedrooms

and a closet. A 12-foot by 20-foot brick addition on the rear of the

building served as a wood storage shed. Rather than creating a unique set of plans for the new station,

Eleventh District Engineer Brevet Brigadier General Orlando M. Poe

resurrected a plan which had been previously used on Chambers Island in

1867 and at Eagle Bluff in 1868. After blasting out a hole for the

cellar, the masons crafted a two-story dwelling red brick dwelling,

29-foot by 25-foot in plan, with an integrated 44-foot tall tower

oriented diagonally into its northeastern corner. The exterior of the

first and second stories of the tower were approximately ten feet square

with buttressed corners, while the tower's upper portion consisted of a

ten-foot octagon. The tower was double-walled, with a circular inner

wall approximately four inches thick and eight feet in diameter. This

cylindrical inner wall supported a cast iron spiral staircase which

wound from the oil storage room in the cellar to a hatch in the lantern

floor. Since these spiral stairs also served as the only means of moving

between floors in the dwelling, steel doors provided access to landings

on both the first and second floors to prevent the spread of any fire in

either the dwelling or tower. The first floor of the dwelling contained

a parlor, kitchen and two bedrooms, and the second floor two bedrooms

and a closet. A 12-foot by 20-foot brick addition on the rear of the

building served as a wood storage shed.

Atop the tower, the gallery floor was sheathed with copper, and

surrounded by an iron hand-railing to provide security to keepers when

cleaning the plate glass panes in the decagonal lantern. As construction

neared completion, the District Lampist arrived, moved the Fourth Order

Fresnel lens from the old tower into the new lantern, and carefully

readjusted the clockwork mechanism to ensure that the light’s

characteristic was maintained. After Peter Bird moved his belongings

into the new station, the old structure was demolished to eliminate

confusion to mariners on the lake.

Since the opening of the new lock at Sault Ste Marie in 1855, there

had been a dramatic increase in both the number and size of vessels

plying Superior’s waters. With the rocky ledge at the harbor entry

precluding entry to all vessels but those of the shallowest draft,

Federal funding had been approved for opening a channel through the

ledge in 1866. Under the direction of an Army Corps of Engineers

officer, locally hired workers blasted a channel 130 feet long and 14

feet deep through the rock ledge, and a pair of timber cribs floated

onto the ice, where they were sunk to mark each side of the cut. While

the new Eagle Harbor Light served as both an excellent coast light and

guide to the harbor entrance, it did nothing to guide vessels through

the barrow channel through the ledge. With the work well underway in

1873, the Engineer in charge of the project recommended the erection of

a pair of range lights to lead mariners through the narrow channel, and

heeding the Engineer’s recommendation, the Lighthouse Board

recommended an appropriation of $8,000 for the construction of range

lights at Eagle Harbor in its 1873 annual report. Since the opening of the new lock at Sault Ste Marie in 1855, there

had been a dramatic increase in both the number and size of vessels

plying Superior’s waters. With the rocky ledge at the harbor entry

precluding entry to all vessels but those of the shallowest draft,

Federal funding had been approved for opening a channel through the

ledge in 1866. Under the direction of an Army Corps of Engineers

officer, locally hired workers blasted a channel 130 feet long and 14

feet deep through the rock ledge, and a pair of timber cribs floated

onto the ice, where they were sunk to mark each side of the cut. While

the new Eagle Harbor Light served as both an excellent coast light and

guide to the harbor entrance, it did nothing to guide vessels through

the barrow channel through the ledge. With the work well underway in

1873, the Engineer in charge of the project recommended the erection of

a pair of range lights to lead mariners through the narrow channel, and

heeding the Engineer’s recommendation, the Lighthouse Board

recommended an appropriation of $8,000 for the construction of range

lights at Eagle Harbor in its 1873 annual report.

Peter Bird’s war injury appears to have worsened over his nine

years as Keeper, as he was removed from office on November 17, 1874, and

superceded by his brother George, who was appointed as Acting Keeper

until he could prove himself. Congress provided funding for establishing

the range lights on March 3, 1875. After a year of service, George Bird

was promoted to full Keeper status on November 17, 1876, but resigned

the position the following July. Stephen Cocking, an Cornishman who had

come to work the Copper mines and ended up serving eleven years as

Keeper of the Gull Rock Light was appointed as Acting Keeper to replace

Bird, and promoted to full keeper status two months later on September

21. Unfortunately, Cocking passed away at the age of 54 on November 21,

1889, and was replaced by Henry Pierce who was newly appointed to the

position.

With visibility in the area of Eagle Harbor frequently reduced by

storms and snow late in the navigation season, the Lighthouse Board

recommended that an appropriation of $5,000 be made for the

establishment of a fog signal station and Eagle Harbor in its 1889

report. While Congress passed a Bill approving the establishment of the

fog signal on February 15, 1893, it continually ignored the Board’s

repeated pleas for funding for six years, until the requested funds were

finally approved on March 2, 1895. With the funding finally available,

Eleventh District Engineer Major Milton B. Adams acted quickly,

approving plans and specifications for the station and awarding

contracts for furnishing both construction materials and the fog signals

equipment within a few weeks of the appropriation. Since a light station

with a steam fog signal was considered to be more than a single keeper

could handle, Lighthouse Board policy called for such stations to be

manned by at least two keepers. Thus, with the impending completion of

the new fog signal, a search was initiated for a First Assistant Keeper

for the station.

Construction on the fog signal began that September with the pouring

of concrete footings 100 feet to the west of the lighthouse. Atop these

footings, timber frame walls were erected and sheathed with planking on

the exterior and smooth iron sheets on the interior. The cavity between

the inner and outer walls was then filled with mixed sawdust and lime to

serve as an insulating and fireproofing layer. The entire exterior of

the structure was then covered with a layer of corrugate iron sheeting,

and given a coat of dark brown paint. After pouring of a concrete floor,

twin steam engines and water supply tanks were installed, and the

boilers vented through a pair of iron stacks protruding from each side

of the roof. A pair of Crosby 10-inch automatic fog whistles were

installed at the opposite end of the roof and plumbed to the boilers.

The entire system was then fired-up and tested at 80-pounds pressure,

and the whistles adjusted to emit a repeated 44-second cycle of a

2-second blast, 12 seconds of silence, a second blast of 6-seconds and a

second period of 24 seconds of silence. William Rohrig was appointed to

the position of Assistant, and reported for duty at Eagle Harbor on

November 11. With the dwelling only sized for a single keeper and his

family, Rohrig was forced to find accommodations in the village, and

moved into his new quarters in time for the fog signal’s official

activation on November 30, 1895. Construction on the fog signal began that September with the pouring

of concrete footings 100 feet to the west of the lighthouse. Atop these

footings, timber frame walls were erected and sheathed with planking on

the exterior and smooth iron sheets on the interior. The cavity between

the inner and outer walls was then filled with mixed sawdust and lime to

serve as an insulating and fireproofing layer. The entire exterior of

the structure was then covered with a layer of corrugate iron sheeting,

and given a coat of dark brown paint. After pouring of a concrete floor,

twin steam engines and water supply tanks were installed, and the

boilers vented through a pair of iron stacks protruding from each side

of the roof. A pair of Crosby 10-inch automatic fog whistles were

installed at the opposite end of the roof and plumbed to the boilers.

The entire system was then fired-up and tested at 80-pounds pressure,

and the whistles adjusted to emit a repeated 44-second cycle of a

2-second blast, 12 seconds of silence, a second blast of 6-seconds and a

second period of 24 seconds of silence. William Rohrig was appointed to

the position of Assistant, and reported for duty at Eagle Harbor on

November 11. With the dwelling only sized for a single keeper and his

family, Rohrig was forced to find accommodations in the village, and

moved into his new quarters in time for the fog signal’s official

activation on November 30, 1895.

As the nineteenth century drew to a close, traffic channels in the

Lake changed as the twin Ports of Duluth and Superior became the

preeminent ports for the shipment of iron and grain to the bustling

industrial centers on the lower lakes. As a result, the Eagle Harbor

Light increased in importance as coast light to serve as a guide to east

and west-bound traffic, and in 1897 the Lighthouse Board considered the

installation of a Second Order Fresnel lens at the station in order to

increase the station’s visible range, however this change was never

undertaken.

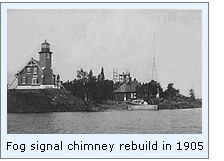

Showing signs of deterioration, the twin iron smokestacks on the fog

signal building were replaced in 1905 by a single brick chimney standing

3 feet square at the base and 40 feet in height, with both boiler

exhausts plumbed into the single chimney. Three years later, a crew

arrived at the station to undertake a number of welcome improvements to

the dwelling. A frame woodshed was erected, and the original brink

woodshed at the rear of the dwelling converted into a kitchen, adding

considerably to the living space within. Central steam heating was also

added through the installation of a boiler in the station’s cellar.

1907 was also likely a memorable year for Keeper John Nolen and First

Assistant Claude Burrows, as they toiled to shoveled 43 tons of coal

into the fog signal boilers in order to keep the whistles screaming

their warning across the lake a station record 544 hours. Showing signs of deterioration, the twin iron smokestacks on the fog

signal building were replaced in 1905 by a single brick chimney standing

3 feet square at the base and 40 feet in height, with both boiler

exhausts plumbed into the single chimney. Three years later, a crew

arrived at the station to undertake a number of welcome improvements to

the dwelling. A frame woodshed was erected, and the original brink

woodshed at the rear of the dwelling converted into a kitchen, adding

considerably to the living space within. Central steam heating was also

added through the installation of a boiler in the station’s cellar.

1907 was also likely a memorable year for Keeper John Nolen and First

Assistant Claude Burrows, as they toiled to shoveled 43 tons of coal

into the fog signal boilers in order to keep the whistles screaming

their warning across the lake a station record 544 hours.

With continuing improvements in illuminating technology, the lamp

within the Fourth Order lens was replaced with an incandescent oil vapor

lamp on June 20, 1913. As a result of this modification the output of

the fixed light was increased from 520 to 1,600 candlepower, and that of

the white flash increased from 5,600 to 42,000 candlepower. Eagle Harbor

was also one of the earliest locations on the Great Lakes to have a US

Navy radio compass transmitter established adjacent to the Life Saving

station in 1918. Two buildings were erected by the Navy to house the

equipment and operating crew assigned to the station.

With the automation of the

Copper Harbor Light in 1919, that light

exhibited an occulting white light. Being located only sixteen miles to

the east of Eagle Harbor, a number of mariners complained that the

characteristics of the two lights were too similar, and requested that

one of the lights be modified to eliminate any confusion. To this end,

the characteristic of the Eagle Harbor light was again modified on May

15, 1924 through the installation of a red segment on the bull’s eyes,

causing the light to show fixed white varied by a bright red flash every

two minutes. That year the decision was also made to add a Second

Assistant at the lighthouse, with William J Miller appointed to the

position that April. With no changes having been made in the

accommodations on the station property, both Miller and First Assistant

Hans Christensen were still forced to make their own living arrangements

in the village. With the automation of the

Copper Harbor Light in 1919, that light

exhibited an occulting white light. Being located only sixteen miles to

the east of Eagle Harbor, a number of mariners complained that the

characteristics of the two lights were too similar, and requested that

one of the lights be modified to eliminate any confusion. To this end,

the characteristic of the Eagle Harbor light was again modified on May

15, 1924 through the installation of a red segment on the bull’s eyes,

causing the light to show fixed white varied by a bright red flash every

two minutes. That year the decision was also made to add a Second

Assistant at the lighthouse, with William J Miller appointed to the

position that April. With no changes having been made in the

accommodations on the station property, both Miller and First Assistant

Hans Christensen were still forced to make their own living arrangements

in the village.

Mariners began complaining that the faded red brick of the Eagle

Harbor tower was difficult to see against gray skies during daylight

hours, and to help the tower serve as a more effective day mark, the

tower sides facing the lake were given a coat of bright white paint on

April 13, 1925.

A work crew arrived at the station in 1828 and removed the

thirty-year old boilers and steam whistles and replaced them with a pair

of Type F diaphone fog signals operated by a diesel powered compressor.

The following year a radiobeacon transmitter was set up in the fog

signal building and wired to an antenna to the west of the building.

Just as each station had its own characteristic light and fog signal

patterns, so each radiobeacon emitted a repeated Morse code signal

unique to that station. The Eagle Harbor radiobeacon characteristic

consisted of repeated groups of one dot and 3 dashes. By receiving the

signals from two such transmitters simultaneously, and knowing the exact

location of each signal, captains out on the lake could accurately

triangulate their position. With the establishment of this radiobeacon,

the Navy compass station across the bay was rendered obsolete, and the

station was thus closed down. A work crew arrived at the station in 1828 and removed the

thirty-year old boilers and steam whistles and replaced them with a pair

of Type F diaphone fog signals operated by a diesel powered compressor.

The following year a radiobeacon transmitter was set up in the fog

signal building and wired to an antenna to the west of the building.

Just as each station had its own characteristic light and fog signal

patterns, so each radiobeacon emitted a repeated Morse code signal

unique to that station. The Eagle Harbor radiobeacon characteristic

consisted of repeated groups of one dot and 3 dashes. By receiving the

signals from two such transmitters simultaneously, and knowing the exact

location of each signal, captains out on the lake could accurately

triangulate their position. With the establishment of this radiobeacon,

the Navy compass station across the bay was rendered obsolete, and the

station was thus closed down.

With the two buildings at the abandoned radio compass station no

longer serving any purpose, the decision was made to move one of the

buildings across the bay to the light station where it could be used as

dwellings for the First and Second Assistant Keepers. To this end, the

lighthouse tender ASPEN arrived in the Harbor with a work crew and a

barge in 1932. While part of the work crew prepared a new foundation for

the structure on at the light station, the remainder of the crew lifted

the structure onto the barge to be towed across the bay. On arrival at

the light station, the dwelling was carefully lifted ashore and hoisted

into position on the awaiting foundation.

In an attempt to reduce operating costs, the Coast Guard removed the

Fresnel lens from the lantern in 1962, and installed a pair of DCB-224

aero beacons in its place. With one of the beacons displaying a

white light and the other red, the characteristic was again changed from

fixed white with red flashes to alternating periods of red and white

light. Equipped with automated bulb changers, the way was now paved for

the station’s automation, which finally came to the station in 1982,

when seaman Jerry McKinney left the station on January 8, the last in a

series of 36 men who served at the station ensuring the way was marked

for mariners making their way across the lake. With automation,

responsibility for maintenance at the station fell to the crew of the

Portage Entry Coast Guard station, who made regular but infrequent

visits to the station to ensure that the light was operating properly. In an attempt to reduce operating costs, the Coast Guard removed the

Fresnel lens from the lantern in 1962, and installed a pair of DCB-224

aero beacons in its place. With one of the beacons displaying a

white light and the other red, the characteristic was again changed from

fixed white with red flashes to alternating periods of red and white

light. Equipped with automated bulb changers, the way was now paved for

the station’s automation, which finally came to the station in 1982,

when seaman Jerry McKinney left the station on January 8, the last in a

series of 36 men who served at the station ensuring the way was marked

for mariners making their way across the lake. With automation,

responsibility for maintenance at the station fell to the crew of the

Portage Entry Coast Guard station, who made regular but infrequent

visits to the station to ensure that the light was operating properly.

In 1982, the Keweenaw County Historical Society obtained temporary

stewardship of the station buildings, and the Society set about

restoring the dwelling and furnishing as it would have appeared at the

dawn of the twentieth century. In 1999 Congress transferred permanent

ownership of the station to the Society, and thus survival of this

historic structure is assured for future generations to enjoy.

Keepers of

this Light

Click here

to see a complete listing of all Eagle Harbor Light keepers compiled by

Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Seeing this Light

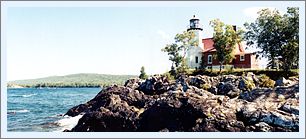

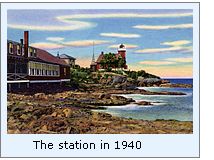

The

Eagle Harbor Light sits on a rocky outcropping

from the Keweenaw, and is seen from across the bay, sitting amongst the

rocks which the station was designed to guard. The buildings now

function as a museum operated by the Keweenaw County Historical Society.

The lighthouse itself is completely refurbished and furnished, and

features mannequins set-up as if they are living in the building. The

fog signal building has been converted into a maritime history museum,

and has some excellent historical information about the numerous ships

that have run-aground in the area, and information about the United

States Lighthouse Service, including keeper’s uniform, logs and USLHS china used by the keepers.

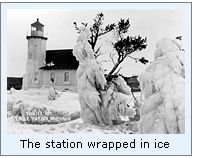

There are also many interesting period photographs showing the

difficulty of conditions at the station during the winter months.

Finding this Lighthouse

Take M26 into the village of Eagle Harbor. As you enter town, turn left

up the gravel road into the lighthouse property at the point where M26

takes a sharp turn to the right. If approaching from the North on M26,

the view at the left above can be seen across the bay just North of the

village.

Contact information

Eagle Harbor Light Station Museum Complex

Star Route 1

Eagle Harbor, MI 49951

(906) 337-1263

Reference Sources

Journals of the US Senate,

Various, 1850 – 1877

Journal of the House of Representatives, Various, 1850 – 1877

Annual report of the Lighthouse Board, various, 1855 – 1909

Annual report of the Lighthouse Service, various, 1910 – 1939

Annual report of the Lake Carriers Association, various, 1905 –

1940

Great Lakes Light List, various, 1861 – 1997

History of Eagle Harbor, Michigan, Clarence J Monette, 1977

History of the Great Lakes, JH Beers Co., 1899

Personal visit to Eagle Harbor on

09/08/1999

Emails with George Hite and Jerry Lenz of Keweenaw County Historical

Society, April 2003

Keeper listings for this light appear

courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|