|

Historical

Information

At the dawn of the

1880’s, the volume of maritime traffic passing between harbors on the

western shore of Lake Michigan and Green Bay and the Straits of Mackinac

exploded. While the St. Helena Island light station lighted the eastern

entry into the Straits, mariners were forced to navigate blind along 100

miles of unlighted upper peninsula coastline before the

Poverty Island

light came into view at the western end of the passage. With treacherous

storms frequent at both ends of the navigation season, mariners

frequently chose to ride out such storms in the lee of points protruding

into the lake along this 100-mile stretch of unlighted shoreline.

Seeking to both make identification of such a refuge easier, and to

mark the shore at an interim point between the two existing lights, the

Lighthouse Board recommended that establishment of a light station on

the end of Point Patterson, approximately midway between St. Helena

Island and Manistique. Unable to determine the need for such a light,

Congress referred the matter to the Commerce Committee for evaluation,

with the Committee returning a favorable report on February 15, 1882. A

bill appropriating $15,000 for the station’s construction passed through

the Senate on May 4, 1882, however the bill failed to pass on a vote in

the House, and the matter was dropped. In reconsideration its

recommendation, the Lighthouse Board determined that Seul Choix Pointe,

approximately 20 miles to the west of Point Patterson actually

represented a better location for the light, and submitted a request for

funding of a light in the revised location in its 1885 annual report.

Evidently this time Congress concurred with the need for the station, as

a $15,000 appropriation for establishing the new station passed both

houses on August 4, 1886.

A survey of Seul Choix Pointe was conducted late that year, and a

6.1-acre site at the southernmost end of the Point selected for the

station, and negotiations for its purchase undertaken with Archibald

Newton, the owner of the property. Newton and his two brothers had early

attained financial success as fishermen in northern Lake Michigan,

establishing a booming town around the natural bay on the eastern shore

of St. Helena Island. Archibald had attained local fame in 1856, when

under his leadership a fleet of vessels sailed from St. Helena to Beaver

Island to drive out the followers of renegade Mormon "King" James Jesse

Strang after his assassination by a couple of his disgruntled flock.

Over the ensuing years, the Newtons spread their fishing operations

westward along the north shore all the way to Seul Choix, and operated a

fleet of schooners out of St. Helena which trading goods for fish with

fishermen throughout the northern end of the lake. While Newton was

universally recognized as the landowner of virtually all of Seul Choix

Pointe, proving clear title to the surveyed property was less than a

simple task, with previous inconsistencies in title documents preventing

transfer of title to the Federal government until June 17, 1889.

In the meantime, plans and specifications for construction of the

station buildings and mechanical systems had been completed and

approved, and with clear title in hand, bids for construction could be

advertised. However, with the closest bid coming in at more than $3,000

beyond the limits of the appropriation, a second round of bids were

sought in the hope that some contractor would be willing to do the work

for less. When this second group of bids came in similarly beyond the

appropriated amount, the Board had no alternative but to request an

additional $3,500 appropriation for the work in its 1890 annual report.

Realizing the important role this light would play to mariners, the

decision was also made to seek funding for the establishment of a

first-class fog signal at the station, and a request for a separate

appropriation of $5,500 for its construction asked in that same report. In the meantime, plans and specifications for construction of the

station buildings and mechanical systems had been completed and

approved, and with clear title in hand, bids for construction could be

advertised. However, with the closest bid coming in at more than $3,000

beyond the limits of the appropriation, a second round of bids were

sought in the hope that some contractor would be willing to do the work

for less. When this second group of bids came in similarly beyond the

appropriated amount, the Board had no alternative but to request an

additional $3,500 appropriation for the work in its 1890 annual report.

Realizing the important role this light would play to mariners, the

decision was also made to seek funding for the establishment of a

first-class fog signal at the station, and a request for a separate

appropriation of $5,500 for its construction asked in that same report.

On August 29, 1891, the lighthouse tender

WARRINGTON departed from

the Detroit Depot bound for Seul Choix Pointe loaded with building

materials and a construction crew under the direction of Ninth District

construction superintendent Todd. Expectations were high that the work

would be carried far enough by the end of the year that the light would

be exhibited at the opening of the 1892 navigation season. However, on

arrival at the site it quickly became evident that the plan to use

rubble stone from the area in building the dwelling cellar was

impossible, as the local stone was found to be altogether too soft and

flaky for the intended purpose. As a result, construction was virtually

halted while the crew waited for a shipment of cement and aggregate from

which to construct the cellar walls. To exacerbate the problem, the fall

of 1891 was particularly stormy, again bringing construction to a halt

on numerous occasions. With the dwelling barely complete, and the

masonry of the tower laid only to a height of 20 feet, it became clear

that there was no way the work would be brought anywhere close to

completion that year.

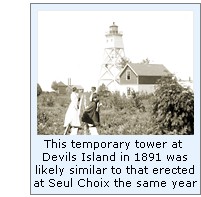

In order to ensure that a light would be exhibited on the opening of

the 1892 navigation season in accordance with the terms of the

appropriation, Ninth District Engineer Major William Ludlow authorized

the erection of a temporary beacon on the point at a cost of $850.

Consisting of an open frame timber structure with diagonal bracing, the

upper part was enclosed to create a service room, and a place to work on

the light during inclement weather. Within the cast iron lantern atop

the service room, a fixed white

Fourth Order Fresnel lens was installed

47 feet above the ground, and at a focal plane of 56 feet above lake

level, making the light visible for a distance of 15 miles in clear

weather. Work on the beacon was completed just in time as the onset of a

particularly bitter winter put an end to construction on the point on

November 16, and the work crew left for the season. Captain Joseph

Fountain, who was serving as keeper of the Beaver Island Harbor Light

was selected as the keeper of the new Seul Choix Pointe light on January

23, and he exhibited the light for the temporary tower on the opening of

the 1892 navigation season.

Colonel

Orlando M. Poe took over for Ludlow as Chief Engineer of the

Ninth Lighthouse District on June 22, 1892 to discover that he had

inherited a veritable rat’s nest at Seul Choix. A combination of poor

planning and shoddy accounting practices were pushing costs far beyond

the amount of the original appropriation. As if the additional costs of

purchasing and shipping concrete, erecting the temporary beacon, and

lost labor awaiting materials and sitting out bad weather weren’t

enough, it was discovered that a serious accounting error had been made.

The costs of the camp outfit, tools and other equipment used in

construction had been charged directly to the Seul Choix appropriation,

when they should have been charged to the general fund, as they would

remain usable in other projects after the construction at Seul Choix was

complete. As a result, Poe called a halt to construction, and

recommended an additional appropriation of $5,500 to cover the shortfall

in the Lighthouse Board’s 1892 annual report, along with a repeated

request for the $5,500 appropriation for establishing the fog signal at

the point. Colonel

Orlando M. Poe took over for Ludlow as Chief Engineer of the

Ninth Lighthouse District on June 22, 1892 to discover that he had

inherited a veritable rat’s nest at Seul Choix. A combination of poor

planning and shoddy accounting practices were pushing costs far beyond

the amount of the original appropriation. As if the additional costs of

purchasing and shipping concrete, erecting the temporary beacon, and

lost labor awaiting materials and sitting out bad weather weren’t

enough, it was discovered that a serious accounting error had been made.

The costs of the camp outfit, tools and other equipment used in

construction had been charged directly to the Seul Choix appropriation,

when they should have been charged to the general fund, as they would

remain usable in other projects after the construction at Seul Choix was

complete. As a result, Poe called a halt to construction, and

recommended an additional appropriation of $5,500 to cover the shortfall

in the Lighthouse Board’s 1892 annual report, along with a repeated

request for the $5,500 appropriation for establishing the fog signal at

the point.

With funding still unforthcoming in the summer of 1893, an inspection

of the construction site indicated that there had been significant

deterioration of the partially erected structures since construction was

halted the prior year. Much of work already done was significantly

damaged that it needed to be torn down and started over, significantly

adding to the costs Poe allowed for in his 1892 request for additional

funding. Moreover, the passage of the 8-hour labor law early in 1893

made it inevitable that labor costs would increase dramatically on the

resumption of construction, as lighthouse crews had historically toiled

from dawn to dusk, a practice which the act eliminated.

Unfortunately, Poe was faced with requesting more funds at the most

inopportune period in decades. Earlier that year, the Reading Railroad

went into receivership, with a number of other smaller railroads falling

in its wake. The situation was quickly exacerbated by the failures of

hundreds of banks and businesses that depended upon the railroads. The

stock market reacted with a dramatic plunge, European investors pulled

their funds out of US markets, and the US economy spiraled into a four

year Depression. With plummeting tax revenues, Congress was hard pressed

to make ends meet, and the problems associated with building a

lighthouse on an far off point in Lake Michigan with a French name that

nobody could pronounce was inevitably pushed to the bottom of the pile.

With funding thus unlikely, Poe conducted an analysis of all funded

projects in the district to identify if there were any unexpended

appropriations which could be reassigned to allow the completion of work

at Seul Choix Pointe, which had now been sitting in a decaying state for

two years. A likely candidate was identified in the St. Mary’s River,

where a $5,000 appropriation for relocating the Upper Range lights had

been made on August 5, 1892, but the work had yet to be started.

Determining the completion of the station at Seul Choix to be more

critical to maritime commerce relocating the range, Poe suggested to the

Board that permission be obtained to redirect the $5,000 appropriation

to Seul Choix, and concurring with the determination the Lighthouse

Board recommended that action to Congress in its annual report for 1894.

Since the solution required no additional funding, Congress approved the

funding reallocation in the Sundry Civil Appropriation Act of August 18,

1894, and also included an appropriation of $2,200 for beginning

construction of the fog signal building. With funding thus unlikely, Poe conducted an analysis of all funded

projects in the district to identify if there were any unexpended

appropriations which could be reassigned to allow the completion of work

at Seul Choix Pointe, which had now been sitting in a decaying state for

two years. A likely candidate was identified in the St. Mary’s River,

where a $5,000 appropriation for relocating the Upper Range lights had

been made on August 5, 1892, but the work had yet to be started.

Determining the completion of the station at Seul Choix to be more

critical to maritime commerce relocating the range, Poe suggested to the

Board that permission be obtained to redirect the $5,000 appropriation

to Seul Choix, and concurring with the determination the Lighthouse

Board recommended that action to Congress in its annual report for 1894.

Since the solution required no additional funding, Congress approved the

funding reallocation in the Sundry Civil Appropriation Act of August 18,

1894, and also included an appropriation of $2,200 for beginning

construction of the fog signal building.

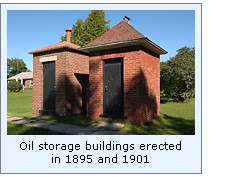

Revised estimates for completing the tower and dwelling were

formulated over the winter of 1894, and bids for the materials needed

for the completion of the work were advertised on March 9, 1895. The

materials and working party were loaded aboard the Lighthouse tender

AMARANTH, and delivered to Seul Choix on the opening of the 1895

navigation season. Work at the point was renewed at a feverish pace, and

by the end of June significant progress had been made. The dwelling had

been completely re-plastered, an oil house was completed, the tower had

been raised to a height of 56’ 4", construction of the boathouse was

nearly complete, masons were cutting limestone arches for the upper

tower windows, and the cast iron stairs had been installed in the tower

to the third platform level. Additionally, the brick fog signal building

had been completed, and the brick foundations for the duplicate steam

boilers completed and awaiting delivery of the boilers and associated

piping. With construction nearing completion at the end of July, the

magnificence of the station’s design was evident. Revised estimates for completing the tower and dwelling were

formulated over the winter of 1894, and bids for the materials needed

for the completion of the work were advertised on March 9, 1895. The

materials and working party were loaded aboard the Lighthouse tender

AMARANTH, and delivered to Seul Choix on the opening of the 1895

navigation season. Work at the point was renewed at a feverish pace, and

by the end of June significant progress had been made. The dwelling had

been completely re-plastered, an oil house was completed, the tower had

been raised to a height of 56’ 4", construction of the boathouse was

nearly complete, masons were cutting limestone arches for the upper

tower windows, and the cast iron stairs had been installed in the tower

to the third platform level. Additionally, the brick fog signal building

had been completed, and the brick foundations for the duplicate steam

boilers completed and awaiting delivery of the boilers and associated

piping. With construction nearing completion at the end of July, the

magnificence of the station’s design was evident.

The duplex dwelling consisted of a red brick structure on a stone

foundation with ashlar limestone above grade to reduce deterioration of

the brick. All trim work was painted in a buff color, and the roof

capped with red metal shingles. The interior of the building was laid

out with four rooms in each apartment, 5 closets a pantry, drawing room

and a vestibule at each entry.

Attached to the dwelling by a covered way, the white painted brick

tower stood 18’ in diameter immediately above the foundation, and

gracefully tapered to a diameter of 12’ 4" in diameter beneath the

gallery. Of double-walled design, the outer wall stood 20"in thickness

at the base and tapered to 17" in thickness at the gallery. The 8’

diameter inner wall stood 9" in thickness, with the two walls separated

by an air space tapering from 29" at the base to 9" at the gallery, with

radial buttresses between the two walls to anchor them together. 86 cast

iron spiral stairs wound their way vertically within the inner cylinder,

passing through 2 landings and leading to a hinged scuttle in the iron

watch room floor. Four arched windows with carved limestone lintels were

located on the compass points in the watch room, and provided an

excellent view of the lake. Attached to the dwelling by a covered way, the white painted brick

tower stood 18’ in diameter immediately above the foundation, and

gracefully tapered to a diameter of 12’ 4" in diameter beneath the

gallery. Of double-walled design, the outer wall stood 20"in thickness

at the base and tapered to 17" in thickness at the gallery. The 8’

diameter inner wall stood 9" in thickness, with the two walls separated

by an air space tapering from 29" at the base to 9" at the gallery, with

radial buttresses between the two walls to anchor them together. 86 cast

iron spiral stairs wound their way vertically within the inner cylinder,

passing through 2 landings and leading to a hinged scuttle in the iron

watch room floor. Four arched windows with carved limestone lintels were

located on the compass points in the watch room, and provided an

excellent view of the lake.

Above the watch room, the gallery was supported by sixteen carved

limestone corbels, and surrounded by a delicate but sturdy iron railing.

Atop the service room, the decagonal third order lantern stood 8 feet in

diameter, and featured nine ¼" thick glass plates, each 31 ¼" wide by 69

¾" in height, and was surmounted by a copper roof with a zinc inner

lining. The fixed white

Third Order Fresnel lens was installed atop a

sturdy cast iron pedestal, which rose from the floor of the service room

into the lantern, placing the lens at a focal plane of 79 feet above

mean lake level. Manufactured by Henry-Lepaute of Paris, the lens

incorporated a lower catadioptric belt of 4 prisms, a dioptric center

drum of 13 elements, and an upper catadioptric belt of 11 prisms.

Illuminated with a state of the art kerosene fueled 3-wick Funck Heap

lamp with lamp plunger and float chamber, the lens was designed to be

visible from a distance of seventeen miles at sea in clear weather

conditions. Above the watch room, the gallery was supported by sixteen carved

limestone corbels, and surrounded by a delicate but sturdy iron railing.

Atop the service room, the decagonal third order lantern stood 8 feet in

diameter, and featured nine ¼" thick glass plates, each 31 ¼" wide by 69

¾" in height, and was surmounted by a copper roof with a zinc inner

lining. The fixed white

Third Order Fresnel lens was installed atop a

sturdy cast iron pedestal, which rose from the floor of the service room

into the lantern, placing the lens at a focal plane of 79 feet above

mean lake level. Manufactured by Henry-Lepaute of Paris, the lens

incorporated a lower catadioptric belt of 4 prisms, a dioptric center

drum of 13 elements, and an upper catadioptric belt of 11 prisms.

Illuminated with a state of the art kerosene fueled 3-wick Funck Heap

lamp with lamp plunger and float chamber, the lens was designed to be

visible from a distance of seventeen miles at sea in clear weather

conditions.

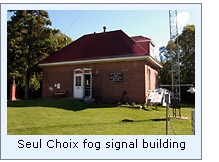

A series of plank walkways connected the dwelling to a brick oil

house, a brick privy, a wood frame boathouse and the 34’ by 20’ brick

fog signal building standing 108 feet southeast of the tower. To provide

steam for the single tone 10" steam whistle mounted above the roof, a

pair of locomotive-style boilers manufactured by the Miami Valley Boiler

Company of Dayton, Ohio sat on brick foundations within the building.

Operating at a pressure of 80 pounds per square inch, the whistles were

sequenced to emit the station characteristic single blast of four second

followed by 26 seconds of silence by a Crosby automatic timing device,

tripped by 3 cams on each cylinder.

Work on the station was complete in August, and the fog signal placed

into operation on September 10, 1895. With the exhibition of the Third

Order lens for the first time on the night of August 15, the temporary

timber skeleton tower was disassembled and the components shipped to the

depot for storage. The fog signal was evidently a useful addition to

navigation as keeper Fountain and Assistant Patrick McCauley fed 51 tons

of coal and 3 cords of wood into the hungry boilers in order to keep the

whistle screaming a station high 573 hours during the 1896 navigation

season. Realizing that managing a first-class light station and such a

busy fog signal was more than a two-man crew could handle efficiently,

the decision was made to add a Second Assistant to the station’s roster.

Without quarters for the additional keeper, the Second Assistant likely

moved in with the First Assistant, which likely made for less than

desirable living conditions for both. Work on the station was complete in August, and the fog signal placed

into operation on September 10, 1895. With the exhibition of the Third

Order lens for the first time on the night of August 15, the temporary

timber skeleton tower was disassembled and the components shipped to the

depot for storage. The fog signal was evidently a useful addition to

navigation as keeper Fountain and Assistant Patrick McCauley fed 51 tons

of coal and 3 cords of wood into the hungry boilers in order to keep the

whistle screaming a station high 573 hours during the 1896 navigation

season. Realizing that managing a first-class light station and such a

busy fog signal was more than a two-man crew could handle efficiently,

the decision was made to add a Second Assistant to the station’s roster.

Without quarters for the additional keeper, the Second Assistant likely

moved in with the First Assistant, which likely made for less than

desirable living conditions for both.

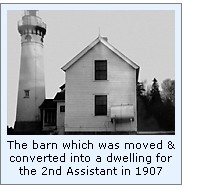

Life at Seul Choix settled into a basic routine until 1901, when a

work crew arrived at the station to install a second iron floor in the

upper portion of the tower to form a watch room and a second oil storage

building was erected. The following year, the twin iron chimneys on the

fog signal building were demolished and replaced by a single brick

chimney into which both boilers were plumbed. Responding to the cramped

living conditions for the assistants, the station barn was relocated

next to the main dwelling and converted into a dwelling for the 2nd

Assistant in 1907.

With the arrival of electricity at the station in1925, the dwelling,

outbuildings and the light itself were electrified and the steam boilers

and whistles removed from the fog signal building and replaced by a

two-tone diaphone. Also this year, the dwelling was modified through the

addition of a wing which provided more suitable accommodations for the

Second Assistant. No longer serving any purpose as a dwelling, the old

converted barn was sold into private ownership, and its new owners moved

it to the shore of one of the nearby lakes where it served as a summer

cottage.

With the assumption of responsibility for the aids of navigation

transferred to the Coast Guard in 1939, three-man crews of seamen began

tending the station. In 1972, the station was finally automated through

the installation of a single

DCB-224 aero beacon with a characteristic

white flash every six seconds, which like the fixed Third Order lens it

replaced, was visible for a distance of 17 miles in clear weather

conditions. The following year, the Coast Guard closed up the station,

leaving the light to operate on an unmanned basis.

No longer serving any government purpose, the station buildings were

sold to the Michigan Department of Natural Resources to serve as a park

on June 20, 1977. After sitting untended for ten years, with the

exception of infrequent visits by Coast Guard AtoN crews to undertake

scheduled maintenance on the aero beacon, the buildings started to

deteriorate rapidly. Realizing the historical significance the station

represented, a group of concerned local citizens banded together to form

the Gulliver Historical Society on October 8, 1987, with their primary

charter being the restoration and preservation of the station and its

history. As part of this process, the Historical Society was successful

in having the station listed on the National Historic Register on August

8. 1988. After obtaining a Michigan Equity Grant the following year, the

Historical Society proudly opened the station to the public at a grand

opening celebration on August 6, 1989. No longer serving any government purpose, the station buildings were

sold to the Michigan Department of Natural Resources to serve as a park

on June 20, 1977. After sitting untended for ten years, with the

exception of infrequent visits by Coast Guard AtoN crews to undertake

scheduled maintenance on the aero beacon, the buildings started to

deteriorate rapidly. Realizing the historical significance the station

represented, a group of concerned local citizens banded together to form

the Gulliver Historical Society on October 8, 1987, with their primary

charter being the restoration and preservation of the station and its

history. As part of this process, the Historical Society was successful

in having the station listed on the National Historic Register on August

8. 1988. After obtaining a Michigan Equity Grant the following year, the

Historical Society proudly opened the station to the public at a grand

opening celebration on August 6, 1989.

Over the ensuing years, as a result of numerous private donations and

successful grant writing campaigns, the dwelling was restored and

re-furnished in time for the station’s centennial in 1995.

Keepers of

this Light

Click here

to see a complete listing of all Seul Choix

Pointe keepers compiled by Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Seeing this Light

From the junction of US-2 and County Rd. 432 in Gulliver,

about 11 miles east of Manistique, go south on CR-432 (Port Inland Rd )

about 4 miles to County Rd. 431. Turn West onto CR-431, a gravel road

which will take you the four miles to the lighthouse. The museum opens

from 10am to 6pm daily from Memorial Day through mid September.

Contact information

For more information on visiting this

Light Station, call: 906-283-3183

Reference Sources

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Board,

various, 1885 – 1909

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Service, various, 1910 – 1929

Form 40 survey of the station, Francis Otter, District Draftsman,

1909

Notice to Mariners, August 8, 1895

Great Lakes Light Lists, various, 1892 – 1995

Detroit Free Press, May 13 & August 29, 1891

Lake Carriers Association annual reports, 1915 & 1925

Keeper listings for this light appear courtesy of Great Lakes Lighthouse

Research |