|

|

Historical

Information

Lying two miles offshore from Gros Cap and

ten miles west of Mackinac Island, St. Helena Island featured a natural

harbor on the its north shore that had long provided shelter for both

Native Americans and Voyageurs seeking shelter from the lake's notorious

southwesterly storms. Upon setting foot on St. Helena in 1850, two

brothers Archie and Wilson Newton quickly realized the commercial

potential the area represented, and after purchasing the 266-acre island

from William Belote in 1853, the Newtons established successful fishing,

trading, lumbering and cooperage operations on the shore of the natural

harbor. It did not take long for others to join them, and a thriving

community of over two hundred people quickly grew to support the

economic base the Newton's had established.

With

the growth in maritime traffic through the late 1850's and 1960's, an

ever increasing number of vessels began to use the harbor, and it not

unusual to find over fifty vessels anchored on the island's lee seeking

respite from the pounding waves. While the anchorage in the area of the

natural harbor was deep and clear, dangerous shoals protruded from both

the eastern and western ends of the island, making passage around the

island extremely dangerous for Captains without close familiarity with

the area. St. Helena Shoal, the worst of these hull rippers, lurked just

below the surface for a distance of almost 1 ¾ miles to the island's

northwest, making the western way unsafe to all but vessels of the

shallowest draft. To both mark the shoals and provide guidance to

coasting mariners, the Lighthouse Board recommended that $14,000 be

appropriated for the construction of a Light at the island's Southeast

point in its 1867 annual report. Congress, however, chose to turn a deaf

ear to the request and the Board's subsequent reiterations until June

10, 1872 when the requested funds were finally appropriated. With

the growth in maritime traffic through the late 1850's and 1960's, an

ever increasing number of vessels began to use the harbor, and it not

unusual to find over fifty vessels anchored on the island's lee seeking

respite from the pounding waves. While the anchorage in the area of the

natural harbor was deep and clear, dangerous shoals protruded from both

the eastern and western ends of the island, making passage around the

island extremely dangerous for Captains without close familiarity with

the area. St. Helena Shoal, the worst of these hull rippers, lurked just

below the surface for a distance of almost 1 ¾ miles to the island's

northwest, making the western way unsafe to all but vessels of the

shallowest draft. To both mark the shoals and provide guidance to

coasting mariners, the Lighthouse Board recommended that $14,000 be

appropriated for the construction of a Light at the island's Southeast

point in its 1867 annual report. Congress, however, chose to turn a deaf

ear to the request and the Board's subsequent reiterations until June

10, 1872 when the requested funds were finally appropriated.

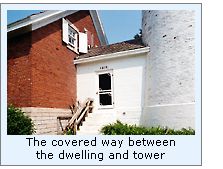

Eleventh District Engineer Orlando

M. Poe reacted quickly, selecting a three acre reservation on

the island and advertising contracts for the necessary materials and

construction labor. Construction began on the island in September of

1872 and continued until November 9, when conditions became to cold for

the mortar to set properly. At the close of the 1872 season, all

foundation work was complete to the first floor level, including the

limestone base of the tower and covered way, and the basement on which

the keeper's dwelling would be erected. The work party returned to the

island on May 9 of the following year and resumed construction. Over the

following month, the double-walled brick tower slowly rose as the masons

carefully laid course on course of red brick. At its completion, the

tower was capped with a prefabricated octagonal cast iron lantern, with

the impressive structure standing sixty-five feet from the foundation to

the center of the lens location. A cast ion spiral staircase wound

around the inner tower wall, terminating at its' uppermost at a small

hinged iron trap door in the floor to provide access to the lantern. The

tower was attached to the brick keeper's dwelling by means of a covered

way, also constructed of red brick. The arched opening at the tower end

of the covered way was outfitted with a tightly fitting iron door,

designed to stop the spread of fire between the two structures. Eleventh District Engineer Orlando

M. Poe reacted quickly, selecting a three acre reservation on

the island and advertising contracts for the necessary materials and

construction labor. Construction began on the island in September of

1872 and continued until November 9, when conditions became to cold for

the mortar to set properly. At the close of the 1872 season, all

foundation work was complete to the first floor level, including the

limestone base of the tower and covered way, and the basement on which

the keeper's dwelling would be erected. The work party returned to the

island on May 9 of the following year and resumed construction. Over the

following month, the double-walled brick tower slowly rose as the masons

carefully laid course on course of red brick. At its completion, the

tower was capped with a prefabricated octagonal cast iron lantern, with

the impressive structure standing sixty-five feet from the foundation to

the center of the lens location. A cast ion spiral staircase wound

around the inner tower wall, terminating at its' uppermost at a small

hinged iron trap door in the floor to provide access to the lantern. The

tower was attached to the brick keeper's dwelling by means of a covered

way, also constructed of red brick. The arched opening at the tower end

of the covered way was outfitted with a tightly fitting iron door,

designed to stop the spread of fire between the two structures.

The dwelling featured expansive

accommodations for a single keeper, featuring a dining room, parlor,

kitchen and office on the first floor, and four bedrooms on the second

floor. A summer kitchen attached to the rear of the dwelling at grade

level and a privy located approximately 30 feet behind the summer

kitchen completed the station's complement of structures. By June 30,

the entire station was complete with the exception of some minor finish

work and the delivery of the Fresnel lens from Paris. Thus, the body of

work party left the island to move onto other projects, leaving a small

crew of four men to finish up. Thomas P Dunn was appointed as the

station's first keeper, and reported for duty at the station on July 29,

to set about moving-in his household goods and assisting the four

workmen in putting the finishing details to his new station. District

Lampist Mr. Crump finally arrived on the island with the new fixed red Third

and a Half Order Fresnel lens in August, and set about

installing the cast iron base and assembling the lens components. With

all work at the station completed, Keeper Dunn officially exhibited the

new station's light for the first time on the evening of September 20,

1873. The dwelling featured expansive

accommodations for a single keeper, featuring a dining room, parlor,

kitchen and office on the first floor, and four bedrooms on the second

floor. A summer kitchen attached to the rear of the dwelling at grade

level and a privy located approximately 30 feet behind the summer

kitchen completed the station's complement of structures. By June 30,

the entire station was complete with the exception of some minor finish

work and the delivery of the Fresnel lens from Paris. Thus, the body of

work party left the island to move onto other projects, leaving a small

crew of four men to finish up. Thomas P Dunn was appointed as the

station's first keeper, and reported for duty at the station on July 29,

to set about moving-in his household goods and assisting the four

workmen in putting the finishing details to his new station. District

Lampist Mr. Crump finally arrived on the island with the new fixed red Third

and a Half Order Fresnel lens in August, and set about

installing the cast iron base and assembling the lens components. With

all work at the station completed, Keeper Dunn officially exhibited the

new station's light for the first time on the evening of September 20,

1873.

Thomas P Dunn continued to serve as the

station's keeper until 1875, when he swapped assignments with Charles

Lousigneau, the keeper at McGulpin's

Point. While not common, there were a number of such instances

of "station swapping," with the Detroit office apparently

willing to facilitate such win-win assignment changes. Few physical

changes were made at the station, and Lousigneau continued to serve as

the station's keeper until May 30, 1888 when he resigned from lighthouse

service. Evidently, Lousigneau's resignation was a surprise to the

Detroit office, since no Keeper is listed at the station until July 7th,

when Charles Marshall, the First Assistant at Waugoshance Light, was

transferred to St. Helena as Acting Keeper. After four years living in

the confines of Waugoshance, the Island must have seemed huge to

Marshall, and he evidently did an admirable job at the station since he

was permanently appointed to the position of Keeper on July 6, 1892. Thomas P Dunn continued to serve as the

station's keeper until 1875, when he swapped assignments with Charles

Lousigneau, the keeper at McGulpin's

Point. While not common, there were a number of such instances

of "station swapping," with the Detroit office apparently

willing to facilitate such win-win assignment changes. Few physical

changes were made at the station, and Lousigneau continued to serve as

the station's keeper until May 30, 1888 when he resigned from lighthouse

service. Evidently, Lousigneau's resignation was a surprise to the

Detroit office, since no Keeper is listed at the station until July 7th,

when Charles Marshall, the First Assistant at Waugoshance Light, was

transferred to St. Helena as Acting Keeper. After four years living in

the confines of Waugoshance, the Island must have seemed huge to

Marshall, and he evidently did an admirable job at the station since he

was permanently appointed to the position of Keeper on July 6, 1892.

On May of 1895 the lighthouse tender AMARANTH

anchored off St. Helena and unloaded a work crew and building materials

for a number of improvements at the station. Through May and June the

crew constructed a new boat house and landing crib with 140 foot long

boat ways, and installed 200 feet of concrete sidewalk. AMARANTH

returned the following month, and unloaded bricks and iron work for the

construction of a 360 gallon capacity brick oil storage shed. In the

early days, lighthouses had been fueled with either sperm or lard oil,

which was delivered by the tenders in rectangular metal containers known

as butts. Since both sperm and lard oil were minimally volatile, the

butts were stored in a dedicated area in the cellar. However, with the

conversion to the infinitely more flammable kerosene as the principal

illuminant, the danger of fire increased dramatically, and the

Lighthouse Board undertook a ten year system-wide program of erecting

separate oil storage of which the construction of the St. Helena oil

house was part.

On May 4, 1896, the lighthouse tender

WARRINGTON arrived at St. Helena with a work party to rebuild the wharf

at St. Helena Harbor and establish a stone crushing plant on shore to

prepare stone for a major repair project being undertaken at Waugoshance

Shoal Light. As part of this project, a huge 100 foot by 90 foot timber

crib was built on the island and towed out to Waugoshance

Light, where it was sunk in place and filled with crushed

limestone from the island. The harbor at St. Helena continued to serve

as the land base for the project through its' completion in October,

whereupon the equipment was reloaded on the WARRINGTON, and returned to

the Detroit lighthouse depot. On May 4, 1896, the lighthouse tender

WARRINGTON arrived at St. Helena with a work party to rebuild the wharf

at St. Helena Harbor and establish a stone crushing plant on shore to

prepare stone for a major repair project being undertaken at Waugoshance

Shoal Light. As part of this project, a huge 100 foot by 90 foot timber

crib was built on the island and towed out to Waugoshance

Light, where it was sunk in place and filled with crushed

limestone from the island. The harbor at St. Helena continued to serve

as the land base for the project through its' completion in October,

whereupon the equipment was reloaded on the WARRINGTON, and returned to

the Detroit lighthouse depot.

In yet another assignment swap, after

twelve years as Keeper of the St. Helena Light, Charles Marshall

transferred to Old Mackinac Point Light Station on November 23, 1900

where he took the lesser position of First Assistant. At the same time

George Legatt, who had served as First Assistant at Old

Mackinac Point Light Station for the past year took over as

Keeper of the St. Helena Light. Unfortunately, Legatt did not last long

on St. Helena, as he drowned the following June, once again leaving the

island without a Keeper. Captain Joseph Fountain, who had eighteen years

of service under his belt at a number of island lights in Lake Michigan

including South Fox and Skillagallee

transferred-in as the fifth St. Helena Island keeper on July 1, 1901.

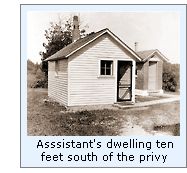

While stations without fog signals were

historically manned by a single keeper, the decision was made to add an

Assistant at St. Helena in 1909. Thus during that summer, a small

one-room cottage was constructed approximately ten feet south of the

privy, and on October 21, Louis J Beloungea was transferred from Squaw

Island where he had been serving for two years as 2nd Assistant

at that station. The Assistant's cottage basically served only as

sleeping quarters for Beloungea, since he ate his meals in the main

dwelling with Keeper Fountain and his family. As can be well imagined,

the location of the Assistant's dwelling a scant ten feet from the privy

created a less than desirable situation, with the associated odors

permeating the small structure, and perhaps contributes to the fact four

Assistants transferred out of the position in as many years. Finally,

the situation was rectified when the dwelling was relocated to an area

approximately one hundred feet to the north of the oil house. While stations without fog signals were

historically manned by a single keeper, the decision was made to add an

Assistant at St. Helena in 1909. Thus during that summer, a small

one-room cottage was constructed approximately ten feet south of the

privy, and on October 21, Louis J Beloungea was transferred from Squaw

Island where he had been serving for two years as 2nd Assistant

at that station. The Assistant's cottage basically served only as

sleeping quarters for Beloungea, since he ate his meals in the main

dwelling with Keeper Fountain and his family. As can be well imagined,

the location of the Assistant's dwelling a scant ten feet from the privy

created a less than desirable situation, with the associated odors

permeating the small structure, and perhaps contributes to the fact four

Assistants transferred out of the position in as many years. Finally,

the situation was rectified when the dwelling was relocated to an area

approximately one hundred feet to the north of the oil house.

Being located relatively close to the

growing town of St. Ignace, the island became a popular place for city

folk to visit. Such visits were not restricted to the summer months,

since being a short three-hour sleigh ride, many people traversed the

ice to the island during the frozen winter months. The Lighthouse

Service annual report for 1913 lauded Keeper Fountain for his rescue of

two men who had almost frozen to death when they lost their way on the

ice while attempting the trip.

The light was automated through the

installation of an acetylene powered lamp in 1922. Equipped with a sun

valve, the lamp was set up to automatically turn on in the cool of

evening, and extinguish itself with the warmth of day. Thus, with the

constant attendance of a keeper no longer necessary, Keeper Wallace Hall

accepted a transfer as Keeper of the Little

Point Sable Light on June 30, 1922. The station was boarded up,

and responsibility for maintenance of the light transferred to the Old

Mackinac Point light keepers, who took their boat to the island whenever

trouble with the light was reported by passing vessels. The light was automated through the

installation of an acetylene powered lamp in 1922. Equipped with a sun

valve, the lamp was set up to automatically turn on in the cool of

evening, and extinguish itself with the warmth of day. Thus, with the

constant attendance of a keeper no longer necessary, Keeper Wallace Hall

accepted a transfer as Keeper of the Little

Point Sable Light on June 30, 1922. The station was boarded up,

and responsibility for maintenance of the light transferred to the Old

Mackinac Point light keepers, who took their boat to the island whenever

trouble with the light was reported by passing vessels.

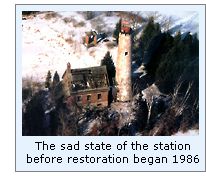

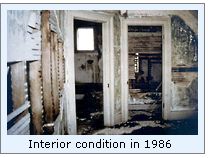

Without the constant attention and care

of a full-time keeper, the station buildings deteriorated, with

proximity to St. Ignace and Mackinaw City leaving the station open to

vandalism. By the 1980's the station was in extremely poor condition.

Everything of any value had been stripped from the structures, all the

windows, doors, banisters and much of the floor had been broken up, with

vandals going so far as to start a fire on the second floor which burned

through the tin kitchen ceiling below and onto the floor. Vandalism of

the boat house and Assistant Keeper's dwelling were so advanced, that

fearing the structures might collapse on someone, the Coast Guard

demolished them to reduce their liability. At some time thereafter,

someone broke down the south wall of the oil house, removing over 1,000

bricks and the iron door, leaving two gaping holes in the side of the

structure. As a final insult, rabbit hunters used the oil house

ventilator for target practice. The condition of the station was so bad,

that the Coast Guard was considering demolishing everything which

remained standing with the exception of the tower and its 300

mm acrylic optic, when a miracle occurred in the Straits. Without the constant attention and care

of a full-time keeper, the station buildings deteriorated, with

proximity to St. Ignace and Mackinaw City leaving the station open to

vandalism. By the 1980's the station was in extremely poor condition.

Everything of any value had been stripped from the structures, all the

windows, doors, banisters and much of the floor had been broken up, with

vandals going so far as to start a fire on the second floor which burned

through the tin kitchen ceiling below and onto the floor. Vandalism of

the boat house and Assistant Keeper's dwelling were so advanced, that

fearing the structures might collapse on someone, the Coast Guard

demolished them to reduce their liability. At some time thereafter,

someone broke down the south wall of the oil house, removing over 1,000

bricks and the iron door, leaving two gaping holes in the side of the

structure. As a final insult, rabbit hunters used the oil house

ventilator for target practice. The condition of the station was so bad,

that the Coast Guard was considering demolishing everything which

remained standing with the exception of the tower and its 300

mm acrylic optic, when a miracle occurred in the Straits.

On behalf of the Great Lakes Lighthouse

Keeper's Association (GLLKA,) the Association's President Dick Moehl was

searching for a restoration project for the Association, and seeing the

potential in the station that was invisible to most, he set about

gathering a small band of people interested in saving the station. In

1986, the GLLKA obtained a thirty-year license to the three acre

reservation and the station structures, and began planning for the

daunting task of restoring the light station. Two years later, the

station was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Realizing that restoration would take an immense amount of manpower,

Dick contacted the Boy Scouts of America, and arranged to receive

assistance of two troops from Ann Arbor and Calumet. On behalf of the Great Lakes Lighthouse

Keeper's Association (GLLKA,) the Association's President Dick Moehl was

searching for a restoration project for the Association, and seeing the

potential in the station that was invisible to most, he set about

gathering a small band of people interested in saving the station. In

1986, the GLLKA obtained a thirty-year license to the three acre

reservation and the station structures, and began planning for the

daunting task of restoring the light station. Two years later, the

station was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Realizing that restoration would take an immense amount of manpower,

Dick contacted the Boy Scouts of America, and arranged to receive

assistance of two troops from Ann Arbor and Calumet.

Every summer since 1989, the Boy Scouts

and GLLKA volunteers have arrived on the island to continue the

restoration. As a result of such broad-based community involvement, the

effort has been rewarded with numerous national and state grants and

awards to assist with the restoration. After ten years of hard work on

the island, GLLKA was close to being eliminated as a potential owner of

the station, when in 1996, Representative Bart Stupak stepped in and

sponsored a Bill through which the station buildings and reservation

were transferred to the GLLKA as part of the Coast Guard Authorization

Bill. In September 2001, after almost ten years of negotiations, the Little

Traverse Conservancy purchased the entire island as a nature

preserve, ensuring that the island will remain open to the public but

will never be developed, thereby helping to ensure the long term

survival of the light station. Every summer since 1989, the Boy Scouts

and GLLKA volunteers have arrived on the island to continue the

restoration. As a result of such broad-based community involvement, the

effort has been rewarded with numerous national and state grants and

awards to assist with the restoration. After ten years of hard work on

the island, GLLKA was close to being eliminated as a potential owner of

the station, when in 1996, Representative Bart Stupak stepped in and

sponsored a Bill through which the station buildings and reservation

were transferred to the GLLKA as part of the Coast Guard Authorization

Bill. In September 2001, after almost ten years of negotiations, the Little

Traverse Conservancy purchased the entire island as a nature

preserve, ensuring that the island will remain open to the public but

will never be developed, thereby helping to ensure the long term

survival of the light station.

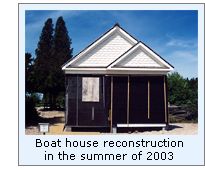

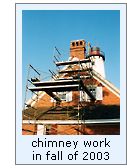

Restoration of the Keepers dwelling is

now nearly complete. The privy and oil house have been restored, the

assistant keepers dwelling has been rebuilt by the Boy Scouts, and work

is well underway on the restoration of the boathouse. Thus, all the

structures comprising the original light station will have been

restored, and the station is again close to its turn of the twentieth

century appearance. Numerous educational programs are held on the island

each year, with the goal of creating a new generation of lighthouse

preservationists, hoping that the work of restoring and maintaining this

beautiful and special place will continue for generations to come. Restoration of the Keepers dwelling is

now nearly complete. The privy and oil house have been restored, the

assistant keepers dwelling has been rebuilt by the Boy Scouts, and work

is well underway on the restoration of the boathouse. Thus, all the

structures comprising the original light station will have been

restored, and the station is again close to its turn of the twentieth

century appearance. Numerous educational programs are held on the island

each year, with the goal of creating a new generation of lighthouse

preservationists, hoping that the work of restoring and maintaining this

beautiful and special place will continue for generations to come.

The work at St. Helena, however, will

never be complete. Exposed as it is to the ravages of the lake,

deterioration is inevitable, and constant repair, repainting and

replacement will be an ongoing necessity. A number of three-day work

sessions and one day walkabouts of the island are held each year, and

anyone interested in helping in the effort with donations of money,

supplies or labor is urged to contact the Association for information.

Keepers of this Light

Click Here to see a complete listing of

all St. Helena Island Light keepers compiled by Phyllis L. Tag of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Seeing this

Light

Sheplers

Ferry Service out of Mackinaw City offers a number of lighthouse cruises

during the summer season. Their "Westward Tour" includes

passes by White Shoal, Grays Reef, Waugoshance and St. Helena Island.

For schedules and rates for this tour, visit their website at: www.sheplerswww.com

or contact them at:

PO Box 250

Mackinaw City, MI 49701

Phone (800) 828-6157

For information on Association membership, St. Helena working weekends, walkabouts and other

activities of GLLKA visit their website at www.gllka.com

or contact the Association at:

Great Lakes Lighthouse Keepers Association

PO Box 219

Mackinaw City, MI 49701

(231) 436-5580

Reference Sources

Annual Reports of the Lighthouse Board, 1853 - 1909

Annual Reports of the Lighthouse Service, 1910 - 1938

Great Lakes Light List, 1876, US Lighthouse Board.

Great Lakes Coast Pilot, 1958. US Army Corps of Engineers.

Historic photographs courtesy of US Cost Guard and GLLKA

Great Lakes Lighthouse Keepers Association archives.

Michigan Historical marker beside Hwy 2 in Gros Cap.

The Office of US. Congressman Bart Stupak.

Keeper listings for this light appear courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|