Historical Information

As

the nineteenth century drew to a close, Chicago’s industries were

suffering congested freight conditions in the city streets, rail

connections and harbor. For those industries wishing to expand or

relocate within the city, skyrocketing land values served as an

insurmountable challenge to many. A group of investors operating under

the name of the Chicago Land Company saw the situation as advantageous

to their interests, and began buying up large tracts of land in the

area of East Chicago some seventeen miles east of the Windy City where

they planned on establishing a major industrial complex. Controlled by

Chicago real estate barons Aldis, Aldis & Northcote with the

backing of Henry Clay Frick of the Carnegie Steel Company and New York

banker J. Kennedy Tod, the group had dreams of creating a first class

harbor with connections to the rail lines which passed along the south

shore and of constructing a canal to connect the harbor to the Calumet

River and the Mississippi beyond.Realizing that

they needed an anchor industry to attract new development, the Land

Company came up with a gutsy proposal whereby they offered to provide

fifty acres of free land to any steel company which would erect a

facility with a minimum value of a million dollars in the new harbor.

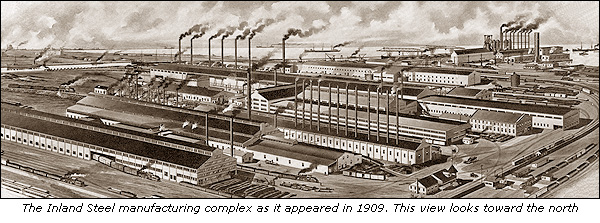

Formed in 1893 after purchasing the idle machinery of Chicago Steel

Works in Chicago Heights, Inland Steel Company had grown to a level of

$350,000 in sales in 1897, and by 1901 found itself outgrowing its

existing facilities and found itself in a financial position in which

the Chicago Land Company’s offer proved extremely attractive. Even

though, at that point, the new “harbor” consisted largely of unimproved

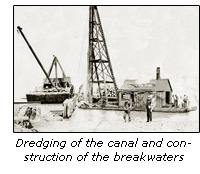

land among the sand dunes.  With Inland Steel

now on board to serve as their anchor industry and a conviction that

related industries would soon follow, in 1901 the Chicago Land Company

entered into a $200,000 contract with Chicago marine contractor Hausler

& Lutz to dredge and erect breakwaters for what would eventually

become known as Indiana Harbor. By the following year, Inland Steel had

completed construction of the first phase of its new plant, and was

operating in the harbor.In 1903, the Chicago

Land Company reorganized under the name of The East Chicago Company.

With this reorganization, the assets of the Standard Steel and Iron

Company, Lake Michigan Land Company and the Calumet Canal Improvement

Company were consolidated, provided direct control of over 7,000 acres

of land in Indiana Harbor, East Chicago and Hammond. After considerable

“speechifying” by such dignitaries as Senator Charles Warren Fairbanks,

Congressmen Charles B. Landis and Congressman Edgar D. Crumpacker,

Indiana Governor Winfield T. Durbin ceremonially pressed an electric

button on October 24, 1903 which sent two monster dredges into action

at the lake end of the new canal which would connect the harbor to the

Calumet River, some 3 miles to the south. With Inland Steel

now on board to serve as their anchor industry and a conviction that

related industries would soon follow, in 1901 the Chicago Land Company

entered into a $200,000 contract with Chicago marine contractor Hausler

& Lutz to dredge and erect breakwaters for what would eventually

become known as Indiana Harbor. By the following year, Inland Steel had

completed construction of the first phase of its new plant, and was

operating in the harbor.In 1903, the Chicago

Land Company reorganized under the name of The East Chicago Company.

With this reorganization, the assets of the Standard Steel and Iron

Company, Lake Michigan Land Company and the Calumet Canal Improvement

Company were consolidated, provided direct control of over 7,000 acres

of land in Indiana Harbor, East Chicago and Hammond. After considerable

“speechifying” by such dignitaries as Senator Charles Warren Fairbanks,

Congressmen Charles B. Landis and Congressman Edgar D. Crumpacker,

Indiana Governor Winfield T. Durbin ceremonially pressed an electric

button on October 24, 1903 which sent two monster dredges into action

at the lake end of the new canal which would connect the harbor to the

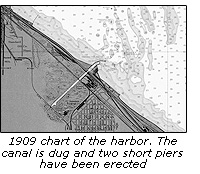

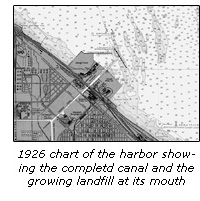

Calumet River, some 3 miles to the south.  Indiana

Harbor was becoming a reality, and a number of other industries began

construction of new facilities there, with American Steel Foundries and

the Buckeye Steel Castings Companies among the first and largest. In

order to add more industrial space around the harbor, at the request of

the East Chicago Company, the mills began dumping their slag into Lake

Michigan, and with the addition of fill brought out from the mainland,

a continuing process of northward expansion of the harbor was underway.With

construction of the canal ongoing, the East Chicago Company began

lobbying for federal maintenance and improvement of Indiana Harbor.

Heeding the call of his influential constituent industries, Indiana

Congressman Edgar D. Crumpacker of Valparaiso quickly introduced a

number of bills calling for the federal government to take over

improvement of the harbor. Among these, House Bill 10447 called for the

establishment of a federal lighthouse to guide vessels into the harbor.

The bill was referred to the Committee on Interstate and Foreign

Commerce, and then relegated to the Subcommittee on the Lighthouse

Establishment, where it was finally discussed on January 16, 1905. With

consideration concurrently under evaluation as to whether the Army

Corps of Engineers should assume responsibility for the harbor, it was

agreed that if and when the harbor were to become a federal

responsibility then lighting the piers and breakwaters would be vitally

necessary. However, until that time no federal action would be taken. Indiana

Harbor was becoming a reality, and a number of other industries began

construction of new facilities there, with American Steel Foundries and

the Buckeye Steel Castings Companies among the first and largest. In

order to add more industrial space around the harbor, at the request of

the East Chicago Company, the mills began dumping their slag into Lake

Michigan, and with the addition of fill brought out from the mainland,

a continuing process of northward expansion of the harbor was underway.With

construction of the canal ongoing, the East Chicago Company began

lobbying for federal maintenance and improvement of Indiana Harbor.

Heeding the call of his influential constituent industries, Indiana

Congressman Edgar D. Crumpacker of Valparaiso quickly introduced a

number of bills calling for the federal government to take over

improvement of the harbor. Among these, House Bill 10447 called for the

establishment of a federal lighthouse to guide vessels into the harbor.

The bill was referred to the Committee on Interstate and Foreign

Commerce, and then relegated to the Subcommittee on the Lighthouse

Establishment, where it was finally discussed on January 16, 1905. With

consideration concurrently under evaluation as to whether the Army

Corps of Engineers should assume responsibility for the harbor, it was

agreed that if and when the harbor were to become a federal

responsibility then lighting the piers and breakwaters would be vitally

necessary. However, until that time no federal action would be taken.

Finally

in 1910, Crumpackers’ continued efforts on behalf of the East Chicago

Company bore fruit. With the passage of the Rivers and Harbors Act of

June 25, 1910, the federal government assumed responsibility for the

long term maintenance and improvement of Indiana Harbor. With an

initial appropriation of $62,000, the Army Corps of Engineers entered

into a contract with the Great Lakes Sock and Dredge Company to enlarge

the harbor and increase the width of the canal to 300 feet and the

depth to 20 feet throughout. Work began in April of 1911, and by July

the dredging had progressed to the point that a number of large vessels

with drafts of 18 and 19 feet had gained entry through the new channel.

Thus, with federal involvement in the project a done deal, Commissioner

George R. Putnam of the fledgling Bureau of Lighthouses had no

alternative but to turn his attention to lighting the entry into the

harbor. However, since the Army Corps improvements at Indiana Harbor

were as yet unfinished, and it had as yet been determined exactly how

far the breakwaters would extend into the lake, the decision was made

to start small, and improve over time. Finally

in 1910, Crumpackers’ continued efforts on behalf of the East Chicago

Company bore fruit. With the passage of the Rivers and Harbors Act of

June 25, 1910, the federal government assumed responsibility for the

long term maintenance and improvement of Indiana Harbor. With an

initial appropriation of $62,000, the Army Corps of Engineers entered

into a contract with the Great Lakes Sock and Dredge Company to enlarge

the harbor and increase the width of the canal to 300 feet and the

depth to 20 feet throughout. Work began in April of 1911, and by July

the dredging had progressed to the point that a number of large vessels

with drafts of 18 and 19 feet had gained entry through the new channel.

Thus, with federal involvement in the project a done deal, Commissioner

George R. Putnam of the fledgling Bureau of Lighthouses had no

alternative but to turn his attention to lighting the entry into the

harbor. However, since the Army Corps improvements at Indiana Harbor

were as yet unfinished, and it had as yet been determined exactly how

far the breakwaters would extend into the lake, the decision was made

to start small, and improve over time.

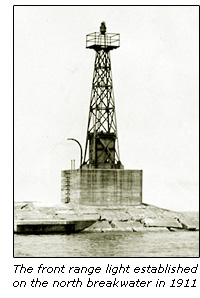

As such, the

first federal navigation aids erected at Indiana Harbor in 1911 took

the form of a pair of prefabricated black skeletal iron range lights

with a small enclosed shed within their bases. The Front Range light

was located at the outer end of the rubble mound north breakwater with

its light standing 17 feet above the concrete surface. The rear range

structure stood 615 feet to shoreward on the same breakwater, its light

standing 27 feet above the base. Both lights were illuminated by

acetylene gas which was stored in cylinders located in the small

enclosed shed at their bases, and outfitted with sun valves which

automatically turned the lights on each day at dusk and off at dawn.

Typical of such acetylene-powered structures, they incorporated a flash

mechanism which caused the lights to flash for a very short duration,

thereby reducing the consumption of the gas. Exhibited for the first

time on the night of September 15th, the Front Range light exhibited a

single flash of 0.3 seconds every second and the rear range a flash of

1 second duration followed by a 2 second eclipse. With

the Army Corps of Engineers construction of rubble mound breakwaters

ongoing, the Lighthouse Bureau determined that on completion of the

current phase of the project the harbor would be deserving of a

significantly larger aid to navigation, and requested an appropriation

of $100,000 to fund the project in 1916. As such, the

first federal navigation aids erected at Indiana Harbor in 1911 took

the form of a pair of prefabricated black skeletal iron range lights

with a small enclosed shed within their bases. The Front Range light

was located at the outer end of the rubble mound north breakwater with

its light standing 17 feet above the concrete surface. The rear range

structure stood 615 feet to shoreward on the same breakwater, its light

standing 27 feet above the base. Both lights were illuminated by

acetylene gas which was stored in cylinders located in the small

enclosed shed at their bases, and outfitted with sun valves which

automatically turned the lights on each day at dusk and off at dawn.

Typical of such acetylene-powered structures, they incorporated a flash

mechanism which caused the lights to flash for a very short duration,

thereby reducing the consumption of the gas. Exhibited for the first

time on the night of September 15th, the Front Range light exhibited a

single flash of 0.3 seconds every second and the rear range a flash of

1 second duration followed by a 2 second eclipse. With

the Army Corps of Engineers construction of rubble mound breakwaters

ongoing, the Lighthouse Bureau determined that on completion of the

current phase of the project the harbor would be deserving of a

significantly larger aid to navigation, and requested an appropriation

of $100,000 to fund the project in 1916.  The

United States declaration of war on Germany on April 6, 1917 had an

incredible impact on the development of Indiana Harbor. The sudden

surge in military production brought huge contracts to the industries

around the harbor, with all working at full capacity to satisfy demand.

With a seemingly endless parade of freighters loaded with iron ore from

the mines on Lake Superior and limestone from the quarries on Lakes

Huron and Michigan making their way into the harbor, the Corps of

Engineers realized that the rubble mound breakwaters were becoming

obsolete, and needed to be replaced with structures of a greater degree

of permanence. As such, plans for the new lighthouse were placed

on the back burner until the new permanent piers were erected. The

United States declaration of war on Germany on April 6, 1917 had an

incredible impact on the development of Indiana Harbor. The sudden

surge in military production brought huge contracts to the industries

around the harbor, with all working at full capacity to satisfy demand.

With a seemingly endless parade of freighters loaded with iron ore from

the mines on Lake Superior and limestone from the quarries on Lakes

Huron and Michigan making their way into the harbor, the Corps of

Engineers realized that the rubble mound breakwaters were becoming

obsolete, and needed to be replaced with structures of a greater degree

of permanence. As such, plans for the new lighthouse were placed

on the back burner until the new permanent piers were erected. With

an appropriation of $200,000 in hand, the Army Corps of Engineers

advertised for bids in July 1919 to rebuild the east breakwater in

concrete and to erect a foundation for the new lighthouse atop a timber

crib in accordance with plans developed by the Bureau of Lighthouses.

On August 21, 1919, the contract for the work was awarded to the Great

Lakes Dredge and Dock Company, with the company’s equipment working in

the harbor soon thereafter. The work moved ahead quickly, as

prefabricated concrete caissons cast at an Army Corps facility on the

waterfront in Milwaukee were used in building the breakwater,

eliminating the need for casting them locally or in place on the

breakwater. By July 1920, 810 feet of the planned 3,024 feet of East

Breakwater was complete, and the lighthouse crib was virtually finished

with the exception of steel ice sheathing. With

an appropriation of $200,000 in hand, the Army Corps of Engineers

advertised for bids in July 1919 to rebuild the east breakwater in

concrete and to erect a foundation for the new lighthouse atop a timber

crib in accordance with plans developed by the Bureau of Lighthouses.

On August 21, 1919, the contract for the work was awarded to the Great

Lakes Dredge and Dock Company, with the company’s equipment working in

the harbor soon thereafter. The work moved ahead quickly, as

prefabricated concrete caissons cast at an Army Corps facility on the

waterfront in Milwaukee were used in building the breakwater,

eliminating the need for casting them locally or in place on the

breakwater. By July 1920, 810 feet of the planned 3,024 feet of East

Breakwater was complete, and the lighthouse crib was virtually finished

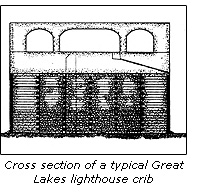

with the exception of steel ice sheathing.  All

told, construction of the timber lighthouse crib required the removal

of 785 cubic yards of lake bed to create a solid base on which to sink

the timber crib. Construction of the crib itself took 196,719 board

feet of lumber shipped in by train from the west coast, 32,633 pounds

of iron and steel, and 2,691 tons of stone to fill the pockets in the

crib. Located 25 feet from the breakwater, the crib was connected to

the breakwater by an iron and steel overhead walkway. Large rooms cast

within the concrete foundation on the crib would serve to house the

station’s full compliment of compressors, generators and heating plant.

Other areas within this structure would serve as storage space for the

supplies required to operate the mechanical systems, such as diesel

fuel and gasoline.Even though the lighthouse

structure itself remained to be built, the Bureau considered activating

the station to be of a sufficiently high priority that the complete fog

signal plant was installed and placed into operation and a temporary

light displayed from an “unpainted post” on the crib standing at a

height of 58 feet above the water – the identical focal plane of the

planned permanent structure. Thus, the new Indiana Harbor East

Breakwater light was exhibited for the first time late in 1920. All

told, construction of the timber lighthouse crib required the removal

of 785 cubic yards of lake bed to create a solid base on which to sink

the timber crib. Construction of the crib itself took 196,719 board

feet of lumber shipped in by train from the west coast, 32,633 pounds

of iron and steel, and 2,691 tons of stone to fill the pockets in the

crib. Located 25 feet from the breakwater, the crib was connected to

the breakwater by an iron and steel overhead walkway. Large rooms cast

within the concrete foundation on the crib would serve to house the

station’s full compliment of compressors, generators and heating plant.

Other areas within this structure would serve as storage space for the

supplies required to operate the mechanical systems, such as diesel

fuel and gasoline.Even though the lighthouse

structure itself remained to be built, the Bureau considered activating

the station to be of a sufficiently high priority that the complete fog

signal plant was installed and placed into operation and a temporary

light displayed from an “unpainted post” on the crib standing at a

height of 58 feet above the water – the identical focal plane of the

planned permanent structure. Thus, the new Indiana Harbor East

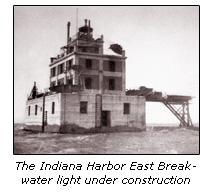

Breakwater light was exhibited for the first time late in 1920. With

funding for completion of the lighthouse finally available in late

1922, work began on the superstructure of the station proper. The new

rectangular building which was erected on the crib served both as a

means for elevating the light and as a dwelling for the station’s

planned compliment of three keepers. Designed in a manner similar to

skyscrapers of the day, an inner framework of steel beams supported

concrete walls and floors and steel stairways. Brick accent areas

surrounding the relatively large steel-framed windows gave the

otherwise austere exterior appearance of the structure a touch of

visual warmth. Centered atop this main structure, a square combination

watchroom and service room supported a circular steel and iron lantern

with helical astragals. As was common with the majority of Great Lakes

lighthouses, the lantern was sized to accommodate a Fourth Order

Fresnel lens, and in order to cause the light to stand out effectively

among the numerous lights of the steel mills along shore, the lens was

equipped with bull’s eyes. Rotation of the lens caused the light to

exhibit a flash as the bulls eyes passed between the light source of

the observer, and created the station’s identifiable characteristic of

a fixed white light with two bright white flashes every 20 seconds.

With construction complete, and all systems in place, James C

Peiterson, the station’s first keeper, made his way up to the lantern

to exhibit the light of the completed Indiana Harbor East Breakwater

Light for the first time on the night of July 14, 1924.Evidently

life at the lighthouse for Peiterson and his two assistants Arthur S.

Almquist and Henry S. Means, must have been relatively uneventful, as

little has been recorded about their lives at the station, either in

government records or in the local newspapers at either Hammond of

Gary. With

funding for completion of the lighthouse finally available in late

1922, work began on the superstructure of the station proper. The new

rectangular building which was erected on the crib served both as a

means for elevating the light and as a dwelling for the station’s

planned compliment of three keepers. Designed in a manner similar to

skyscrapers of the day, an inner framework of steel beams supported

concrete walls and floors and steel stairways. Brick accent areas

surrounding the relatively large steel-framed windows gave the

otherwise austere exterior appearance of the structure a touch of

visual warmth. Centered atop this main structure, a square combination

watchroom and service room supported a circular steel and iron lantern

with helical astragals. As was common with the majority of Great Lakes

lighthouses, the lantern was sized to accommodate a Fourth Order

Fresnel lens, and in order to cause the light to stand out effectively

among the numerous lights of the steel mills along shore, the lens was

equipped with bull’s eyes. Rotation of the lens caused the light to

exhibit a flash as the bulls eyes passed between the light source of

the observer, and created the station’s identifiable characteristic of

a fixed white light with two bright white flashes every 20 seconds.

With construction complete, and all systems in place, James C

Peiterson, the station’s first keeper, made his way up to the lantern

to exhibit the light of the completed Indiana Harbor East Breakwater

Light for the first time on the night of July 14, 1924.Evidently

life at the lighthouse for Peiterson and his two assistants Arthur S.

Almquist and Henry S. Means, must have been relatively uneventful, as

little has been recorded about their lives at the station, either in

government records or in the local newspapers at either Hammond of

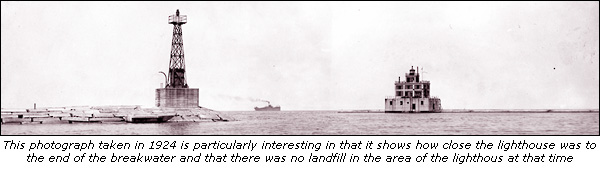

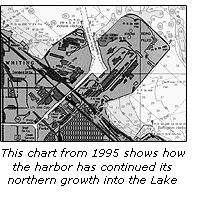

Gary.  America’s steel manufacturers were

now supplying the world. The complex of steel mills and ancillary

industries located around Indiana Harbor continued their northward

expansion into the lake, and as the land mass around the harbor grew,

the entrance to the harbor moved northward and westward with it. While

the Army Corps of Engineers continued extending the east breakwater

northward so that it continued to adequately serve the harbor entry,

the massive lighthouse and its crib now found themselves situated far

from the outer end of the elongated breakwater. With land now pushing

ever closer toward the side of the breakwater inland of the lighthouse,

virtually all of the breakwater landward of the lighthouse was removed,

allowing easier access to the industrial facilities to the north. As

such, the lighthouse now served to mark the inner end of the

breakwater, with the outer end unlighted. America’s steel manufacturers were

now supplying the world. The complex of steel mills and ancillary

industries located around Indiana Harbor continued their northward

expansion into the lake, and as the land mass around the harbor grew,

the entrance to the harbor moved northward and westward with it. While

the Army Corps of Engineers continued extending the east breakwater

northward so that it continued to adequately serve the harbor entry,

the massive lighthouse and its crib now found themselves situated far

from the outer end of the elongated breakwater. With land now pushing

ever closer toward the side of the breakwater inland of the lighthouse,

virtually all of the breakwater landward of the lighthouse was removed,

allowing easier access to the industrial facilities to the north. As

such, the lighthouse now served to mark the inner end of the

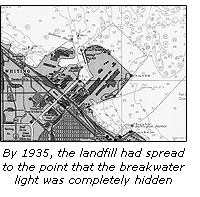

breakwater, with the outer end unlighted. This

problem was further exacerbated by the fact that with the man-made land

growing by leaps and bounds to the north, the light became virtually

hidden by the land and increasingly difficult for mariners to see from

the lake. In order to make the structure noticeable, floodlights were

installed on all four sides of the structure in 1931, but the effort

was futile. The Bureau of Lighthouses was forced to face the

realization that due to its construction and massive size, there was no

way the lighthouse could be relocated to the end of the breakwater. The

only option was to replace the expensive structure a scant decade after

it had been established.By the early 1930’s,

advances in the reliability of both illumination and diaphone fog

signal systems had reached the point that virtually unattended

lighthouses were becoming a reality. Thus the possibility of reducing

the manpower required through the establishment of an automated system

on the extended breakwater was particularly attractive. Also at this

time, Lighthouse Bureau engineers F. P. Dillon and W. G. Will had been

working on a modular design for breakwater and pierhead beacons for use

on the Great Lakes. This

problem was further exacerbated by the fact that with the man-made land

growing by leaps and bounds to the north, the light became virtually

hidden by the land and increasingly difficult for mariners to see from

the lake. In order to make the structure noticeable, floodlights were

installed on all four sides of the structure in 1931, but the effort

was futile. The Bureau of Lighthouses was forced to face the

realization that due to its construction and massive size, there was no

way the lighthouse could be relocated to the end of the breakwater. The

only option was to replace the expensive structure a scant decade after

it had been established.By the early 1930’s,

advances in the reliability of both illumination and diaphone fog

signal systems had reached the point that virtually unattended

lighthouses were becoming a reality. Thus the possibility of reducing

the manpower required through the establishment of an automated system

on the extended breakwater was particularly attractive. Also at this

time, Lighthouse Bureau engineers F. P. Dillon and W. G. Will had been

working on a modular design for breakwater and pierhead beacons for use

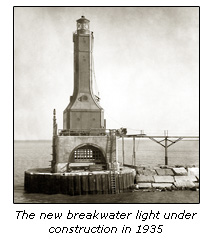

on the Great Lakes. Incorporating

prefabricated cast iron and steel components, these inexpensive $35,000

structures stood approximately 40 feet tall from base to lantern, and

were designed to be relatively easy to erect and disassemble if

required. With plans already in place to install three of these new

structures at Conneaut and Huron Harbors on Lake Erie, and on the new

concrete breakwater at Port Washington, the decision was made to order

an additional set of components for use at the outer end of the

breakwater at Indiana Harbor. As was the case

at Port Washington, the structure at Indiana Harbor was erected atop a

large elevated concrete pier with arched openings in order to increase

its focal plane to 78 feet. This new East Breakwater light was erected

and exhibited for the first time in 1935. In order to provide safe

access to keepers along the breakwater when making their way from the

old lighthouse to the new one when storm-driven waves were crashing

across its surface, an iron and steel elevated walkway was erected on

the breakwater, and the new light was built and exhibited in 1935. Incorporating

prefabricated cast iron and steel components, these inexpensive $35,000

structures stood approximately 40 feet tall from base to lantern, and

were designed to be relatively easy to erect and disassemble if

required. With plans already in place to install three of these new

structures at Conneaut and Huron Harbors on Lake Erie, and on the new

concrete breakwater at Port Washington, the decision was made to order

an additional set of components for use at the outer end of the

breakwater at Indiana Harbor. As was the case

at Port Washington, the structure at Indiana Harbor was erected atop a

large elevated concrete pier with arched openings in order to increase

its focal plane to 78 feet. This new East Breakwater light was erected

and exhibited for the first time in 1935. In order to provide safe

access to keepers along the breakwater when making their way from the

old lighthouse to the new one when storm-driven waves were crashing

across its surface, an iron and steel elevated walkway was erected on

the breakwater, and the new light was built and exhibited in 1935.  The

light in the old structure was electrified and downgraded to a 2,600

candlepower green 300 mm optic and renamed the “Indiana Harbor East

Breakwater Inner light.” In this guise it continued to serve as the

dwelling for the keepers of the harbor lights through the end of the

days of the Bureau of Lighthouses and after the Coast Guard assumed

responsibility for the nation’s aids to navigation in 1939. The Coast

Guard continued to use the structure until 1970 when the building was

largely abandoned. At this time the station’s light was further

downgraded to 1,100 candlepower and renamed the “Indiana Harbor Light

5,” reflecting its new status as a minor aid to navigation within the

harbor.Likely costing too much to maintain, and

perhaps serving as an attractive nuisance, the superstructure of the

lighthouse was demolished at some time in the mid 1980’s, leaving only

the concrete crib and walkway which connected the structure to the

breakwater. In order to allow it to continue to serve as a harbor aid,

a white cylindrical “D9” tower with horizontal green band was erected

on the crib, and today emits a green flash every 2.5 seconds. The

light in the old structure was electrified and downgraded to a 2,600

candlepower green 300 mm optic and renamed the “Indiana Harbor East

Breakwater Inner light.” In this guise it continued to serve as the

dwelling for the keepers of the harbor lights through the end of the

days of the Bureau of Lighthouses and after the Coast Guard assumed

responsibility for the nation’s aids to navigation in 1939. The Coast

Guard continued to use the structure until 1970 when the building was

largely abandoned. At this time the station’s light was further

downgraded to 1,100 candlepower and renamed the “Indiana Harbor Light

5,” reflecting its new status as a minor aid to navigation within the

harbor.Likely costing too much to maintain, and

perhaps serving as an attractive nuisance, the superstructure of the

lighthouse was demolished at some time in the mid 1980’s, leaving only

the concrete crib and walkway which connected the structure to the

breakwater. In order to allow it to continue to serve as a harbor aid,

a white cylindrical “D9” tower with horizontal green band was erected

on the crib, and today emits a green flash every 2.5 seconds.

One

can only wonder how many of the mariners who pass this light today have

the slightest inkling of the original purpose of that huge concrete

crib on which it sits.

Seeing this Light

Because

the lighthouse and old crib are located on a

private breakwater, and there are numerous large

buildings between any public access areas and the

lighthouse, the lights are virtually impossible to

see from the

land. Either a private boat or a vessel chartered from a local

fisherman

represent the only opportunitis to obtain a good view of this light.

Both the Great Lakes Lighthouse Keepers Association and the United

States Lighthouse Society offer infrequent tours of the suth end of

Lake Michigan, both of which have always provided great close-up views

of this and the other lighthouses of the area. GPS Coordinates

Original 1924 lighthouse crib: 41°40'27.41"N x 87°26'19.64"W

1935 Lighthouse: 41°40'50.88"N x 87°26'27.99"W

Reference sourcesNew York Times newspaper articles, various

The Railway Age, Vol 31, 1901

Chicago Securities, The Chicago Directory Company, 1905.

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Board, various

Annual reports of the Lake Carriers Association, various

Astandard History of Lake County, Lewis Publishing Company, 1915

Annual Reports of the Department of COmmerce, various

Hammond Times newspaper articles, various

A Guide to the Hoosier State, Teachers College, 1941

|