|

Historical Information

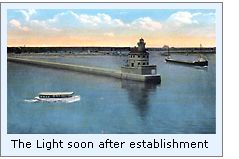

Just offshore, a narrow ten-mile long sand bar stretches between the

twin ports of Duluth and Superior. Reputedly the longest freshwater sand

bar in the world, the bar is split by a natural opening in its'

approximate center. Appropriately, the bar on the Minnesota side of the

opening is known as Minnesota Point, and the bar on the Wisconsin side

is known as Wisconsin Point.

As the twin ports of Duluth and Superior began to grow in their

importance as ports, the quantity of vessel traffic making its way

through this opening began to increase. In order to make passage safer,

in 1856 the Lighthouse Board constructed a stone tower and keepers

dwelling at the end of Minnesota Point for a total cost of $13,700.

After the channel was cut through Minnesota Point at the Duluth

end in 1872 and the Duluth

South Breakwater Light was established to mark the the new entry,

maritime traffic bound for Duluth no longer needed to enter the harbor

through the circuitous gap, and thus the opening began to be used solely

for Superior traffic.

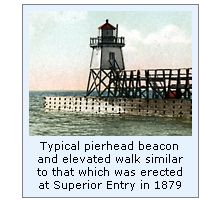

With the construction of protective timber piers at each side of the

entry, a wood-framed pierhead beacon was erected on the end of the north

pier in 1879, and exhibited for the first time on the night of September

1 of that year. With the Army Corps of Engineers continuing to dredge

and enlarge the opening, the pierhead light was temporarily discontinued

in 1880, and the old Minnesota Point light reactivated until work on the

improved piers had progressed to a point that the pierhead beacon could

be reestablished. This work was completed in 1885, and the pierhead

beacon reestablished on the North Pierhead. With the establishment of

this beacon, the old Minnesota Point Light was deactivated, and the

dwelling refurbished to serve as quarters for the Keeper of the new

light. With the construction of protective timber piers at each side of the

entry, a wood-framed pierhead beacon was erected on the end of the north

pier in 1879, and exhibited for the first time on the night of September

1 of that year. With the Army Corps of Engineers continuing to dredge

and enlarge the opening, the pierhead light was temporarily discontinued

in 1880, and the old Minnesota Point light reactivated until work on the

improved piers had progressed to a point that the pierhead beacon could

be reestablished. This work was completed in 1885, and the pierhead

beacon reestablished on the North Pierhead. With the establishment of

this beacon, the old Minnesota Point Light was deactivated, and the

dwelling refurbished to serve as quarters for the Keeper of the new

light.

With the Army Engineer’s continuing to work on the piers, the

decision was made to relocate the beacon across the channel to the

longer south pier in 1892. After the beacon was transported across the

channel and bolted in its new home, an elevated walk was erected from

the beacon leading toward the shore to provide the Keeper with safe

access to the light during stormy weather when waves washed across the

surface of the pier. With the old Minnesota Point dwelling now

inconveniently located on the opposite side of the channel, cost

estimates and plans were also drawn up for the erection of a duplex

keepers dwelling on the Wisconsin side of the entry. Also this year, the

Lighthouse Board recommended the establishment of a fog signal on the

south pier to serve as a guide to vessels making the entry at night and

during thick weather, and requested an appropriation of $5,500 for its

establishment.

1883 saw major changes at Superior entry with the arrival of a work

crew at the site at the opening of the navigation season. Over the

summer, the duplex dwelling with a six-room apartment on each side was

built, and after erection of a boathouse, barn and 360-gallon capacity

brick oil storage building, the buildings were connected with walkways

and the station enclosed by a 200-foot by 200-foot picket fence.

That summer, work began on construction of a 20-foot by 40-foot steam

fog signal building behind the beacon at the end of the south pier. A

timber frame structure, its exterior walls were covered with corrugated

iron sheets, and the inner walls with smooth iron sheeting. Within the

building, a pair of locomotive-style steam boilers were installed and

plumbed into a pair of 6-inch Scotch whistles, which were mounted on the

iron roof of the structure. After the elevated walkway was connected to

the fog signal building and extended an additional 100 feet toward the

shore, work on the fog signal was completed and the signal placed in

operation on August 27, 1893. It would appear that the new fog signal

was indeed a valuable enhancement to navigation, as two years after its

establishment, the keepers toiled to feed 44 tons of coal into the

hungry boilers to keep the whistles screaming their warning across

Superior for a station record 895 hours.

In 1898, the decision was made to add a second light on the south

pier to serve as a rear range to the pierhead beacon to help mariners

locate the course into the channel. With work underway at the Devils

Island light station to replace the temporary timber-framed beacon on

the island with a permanent iron structure, plans were put in place to

move the old beacon to Superior Entry to serve as the new rear beacon.

However, with the lens for the new Devils Island tower unavailable, and

delaying the availability of that structure, a temporary post was

erected on the south pier 1,650 feet behind the pierhead light, and

exhibited for the first time on the night of November 30, 1897.

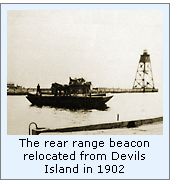

With the installation of the lens in the iron tower on Devils Island

late in the summer of 1901, the old timber beacon was removed from the

island and shipped to Superior. On erection on the south pier, the

lantern was outfitted with a fixed white Fourth Order Fresnel

lens. With

the work completed close to the end of the navigation season, the new

rear range light was not exhibited from the relocated structure until

the opening of the 1902 navigation season on April 1, 1902. With the installation of the lens in the iron tower on Devils Island

late in the summer of 1901, the old timber beacon was removed from the

island and shipped to Superior. On erection on the south pier, the

lantern was outfitted with a fixed white Fourth Order Fresnel

lens. With

the work completed close to the end of the navigation season, the new

rear range light was not exhibited from the relocated structure until

the opening of the 1902 navigation season on April 1, 1902.

The Army Corps of Engineers were back at work at Superior Entry in

1905, erecting new concrete piers to the outside of the old timber

structures. With plans to remove the old piers on their completion, it

was clear that the existing front range on the pierhead, fog signal and

rear range would need to be relocated to the new concrete piers on their

completion. Estimating the cost of erecting new structures on the

concrete piers to be $20,000, the Lighthouse Board requested an

appropriation of that amount in its annual report for 1905, and began

working on plans and specifications for the new structures. As is all

too frequently the case, the greatest of man’s plans stood like twigs

in the face of Mother Nature’s fury when a violent storm swept across

Lake Superior on November 27. By the time the storm had abated the

following day, the Superior Entry Keepers were faced with an incredible

scene of devastation. Waves smashing across the pier had snapped the

12-inch timbers of the front beacon like matchsticks, completely

carrying the structure away, along with 250 feet of the elevated walk.

The roof and upper two thirds of the fog signal building were completely

gone, along with 40 tons of coal which had been swept from the hopper.

Repair work began immediately with the temporary rebuilding of the fog

signal building, and the erection of a temporary frame lantern installed

atop the structure’s roof. However, with winter putting an end to the

work, the fog signal and light were not reactivated until April 15 of

the following year. The Army Corps of Engineers were back at work at Superior Entry in

1905, erecting new concrete piers to the outside of the old timber

structures. With plans to remove the old piers on their completion, it

was clear that the existing front range on the pierhead, fog signal and

rear range would need to be relocated to the new concrete piers on their

completion. Estimating the cost of erecting new structures on the

concrete piers to be $20,000, the Lighthouse Board requested an

appropriation of that amount in its annual report for 1905, and began

working on plans and specifications for the new structures. As is all

too frequently the case, the greatest of man’s plans stood like twigs

in the face of Mother Nature’s fury when a violent storm swept across

Lake Superior on November 27. By the time the storm had abated the

following day, the Superior Entry Keepers were faced with an incredible

scene of devastation. Waves smashing across the pier had snapped the

12-inch timbers of the front beacon like matchsticks, completely

carrying the structure away, along with 250 feet of the elevated walk.

The roof and upper two thirds of the fog signal building were completely

gone, along with 40 tons of coal which had been swept from the hopper.

Repair work began immediately with the temporary rebuilding of the fog

signal building, and the erection of a temporary frame lantern installed

atop the structure’s roof. However, with winter putting an end to the

work, the fog signal and light were not reactivated until April 15 of

the following year.

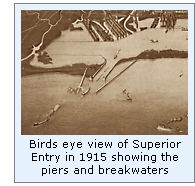

Congress responded to the previous year’s request with an

appropriation of $20,000 on June 30, 1906, however with the Army Corps

of Engineers still working on the new concrete piers, the construction

was postponed pending the completion of the new structures. By 1910, the

Corps of Engineers had revised their plans for Superior Entry, deciding

to construct two long concrete arrowhead breakwaters outside of the

piers in order to create a large stilling basin. With these

enhancements, the newly formed Lighthouse Establishment was forced to

rethink its plan for lighting the harbor entry. Determining that it

would be best to erect the fog signal and main entry light at the end of

the South Breakwater and to establish unmanned acetylene beacons on the

piers, it estimated that the total cost of construction would now reach

$45,000, which was $25,000 beyond the Congressional appropriation of

1906, and requested a second appropriation of $25,000. Congress

responded with the requested secondary appropriation on March 4, 1911,

and preliminary plans for the structures were drawn up and approved soon

thereafter, and by July, the Army Corps of Engineers had completed work

on the 11 ½ foot high concrete base for the new South Breakwater

Pierhead light. Contracts for construction were awarded on June 30,

1912, and construction began almost immediately. Congress responded to the previous year’s request with an

appropriation of $20,000 on June 30, 1906, however with the Army Corps

of Engineers still working on the new concrete piers, the construction

was postponed pending the completion of the new structures. By 1910, the

Corps of Engineers had revised their plans for Superior Entry, deciding

to construct two long concrete arrowhead breakwaters outside of the

piers in order to create a large stilling basin. With these

enhancements, the newly formed Lighthouse Establishment was forced to

rethink its plan for lighting the harbor entry. Determining that it

would be best to erect the fog signal and main entry light at the end of

the South Breakwater and to establish unmanned acetylene beacons on the

piers, it estimated that the total cost of construction would now reach

$45,000, which was $25,000 beyond the Congressional appropriation of

1906, and requested a second appropriation of $25,000. Congress

responded with the requested secondary appropriation on March 4, 1911,

and preliminary plans for the structures were drawn up and approved soon

thereafter, and by July, the Army Corps of Engineers had completed work

on the 11 ½ foot high concrete base for the new South Breakwater

Pierhead light. Contracts for construction were awarded on June 30,

1912, and construction began almost immediately.

The concrete foundation for the Main Light and fog signal contained

vaulted cellar rooms for the storage of oil and paint, along with a

large tank for drinking water. Atop this foundation, the main structure

took the shape of an oblong two-story reinforced concrete building with

rounded ends. Structural steel framing within the building carried

concrete floors, and all interior walls were lined with plaster-finished

terra cotta tile. Inner partition walls were of expanded metal with a

smooth coating of plaster, and the stairs between the decks of cast

iron. The first deck served as a mechanical room, housing a pair of

compressors powered by 22-horsepower inline gasoline engines to supply

air to the fog signal, a steam heating plant, toilet and cold storage

areas. The second floor made up the living quarters, with a kitchen,

living room, three bedrooms and a bathroom. The circular tower rose

through the sheet metal roof at the offshore end of the building, with a

spiral stairway leading from The concrete foundation for the Main Light and fog signal contained

vaulted cellar rooms for the storage of oil and paint, along with a

large tank for drinking water. Atop this foundation, the main structure

took the shape of an oblong two-story reinforced concrete building with

rounded ends. Structural steel framing within the building carried

concrete floors, and all interior walls were lined with plaster-finished

terra cotta tile. Inner partition walls were of expanded metal with a

smooth coating of plaster, and the stairs between the decks of cast

iron. The first deck served as a mechanical room, housing a pair of

compressors powered by 22-horsepower inline gasoline engines to supply

air to the fog signal, a steam heating plant, toilet and cold storage

areas. The second floor made up the living quarters, with a kitchen,

living room, three bedrooms and a bathroom. The circular tower rose

through the sheet metal roof at the offshore end of the building, with a

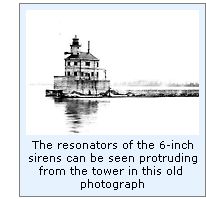

spiral stairway leading from  the second floor. The circular tower

protruded from the offshore end of the building, and featured two

floors, the lowest of which housed a pair of six-inch air sirens with

their resonators protruding out the wall, and the second serving as a

service room. Atop the service room, a copper-roofed circular lantern

room with helical astragals, housed a fixed Fourth Order Fresnel with a

rotating screen within the lens. Mounted on ball bearings and driven by

a clockwork motor, the screen rotated around the lamp imparting a

repeated isophase occulting characteristic of 5 seconds of light

followed by 5 seconds of darkness. Sitting 70 feet above lake level, the

2,900 candlepower lamp was thus visible for a distance of 16 miles in

clear weather.

the second floor. The circular tower

protruded from the offshore end of the building, and featured two

floors, the lowest of which housed a pair of six-inch air sirens with

their resonators protruding out the wall, and the second serving as a

service room. Atop the service room, a copper-roofed circular lantern

room with helical astragals, housed a fixed Fourth Order Fresnel with a

rotating screen within the lens. Mounted on ball bearings and driven by

a clockwork motor, the screen rotated around the lamp imparting a

repeated isophase occulting characteristic of 5 seconds of light

followed by 5 seconds of darkness. Sitting 70 feet above lake level, the

2,900 candlepower lamp was thus visible for a distance of 16 miles in

clear weather.

On establishment of the new lights, the old South Pierhead range and

fog signal were discontinued, and the structures demolished.

The air siren equipment was removed from the tower in 1937, and a

Type F diaphone fog signal installed, and the following year a radiobeacon was

installed at the station.

The station was automated in 1970 with the installation of a rotating

DCB-224 aero beacon which today still sends its green light 22 miles

across the lake every 5 seconds.

Keepers of

this Light

Click here

to see a complete listing of all Wisconsin Point Light keepers compiled

by Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Seeing this Light

The first stop on our 1999 Fall tour, Wisconsin Point Light sits at the

entrance to Superior Harbor on a pier jutting from the end of a three

mile spit of land, which protects the ore docks and the harbor.

It was a blustery day, so we bundled-up for the walk along the pier. The

walk was somewhat difficult, since most of the pier was comprised of

large chunks of concrete, placed in a seemingly random arrangement, with

only the last 100 feet being cast concrete. As we neared the flat concrete section, increasing numbers of gulls that

had been resting on the pier took wing. With the brisk westerly wind,

they appeared to hover above the pier.

It was a blustery day, so we bundled-up for the walk along the pier. The

walk was somewhat difficult, since most of the pier was comprised of

large chunks of concrete, placed in a seemingly random arrangement, with

only the last 100 feet being cast concrete. As we neared the flat concrete section, increasing numbers of gulls that

had been resting on the pier took wing. With the brisk westerly wind,

they appeared to hover above the pier.

The lighthouse itself is quite attractive, since its' concrete sides and

steel roof are gracefully rounded unlike any others we have seen. Having been

relatively recently painted, the white, red and black color scheme

contrasted beautifully with the grayish-blues of the cool Fall day.

Finding this Light

Taking 53 North toward Superior close to the point at which the divided

highway ends, look for Moccasin Mike Rd. on the right. Turn onto Moccasin

Mike Rd. and follow it around the end of the bay. Wisconsin Point Rd.

will be seen to the left. Turn left on Wisconsin Point Rd. and continue

to the end of the point, approximately 2 miles. From the Northernmost

tip of Wisconsin Point, the view in the photo above left can be seen.

Backtrack approximately 1/3 of a mile, and take the road to the left to

gain access to the pier and the lighthouse itself.

Reference Sources

Inventory of Historic Light Stations,

National Parks Service,

1994.

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Board, various, 1879 – 1909

Annual reports of the Commissioner of Lighthouses, various, 1910

– 1939

Annual reports of the Lake Carrier’s Association, 1903 – 1940

Great Lakes Light Lists, various, 1876 - 1979

Personal visit to Wisconsin Point on

09/05/1999

Photographs from author's personal

collection.

Keeper listings for this light appear courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|