|

Historical information

The north shore of Superior has always been a hazardous area to

mariners. Sluggish compass reaction combined with huge deposits of iron

in the rocks along the shore play havoc with navigation. Nowhere is this

variation greater than along the shoreline between Two Harbors and

Beaver Bay where mariners are warned in the Great Lakes Coast Pilot to

expect total compass deviations of 2.2 degrees, with many a mariner

ending up on the rocks while making his way along the north shore at

night. Combine this magnetic aberration with a major storm, and you have

a natural recipe for disaster. Such was the case in 1905, when a series

of back to back storms between November 27th and 29th

whipped the big lake into a froth, causing the loss or damage of 29

vessels and over 200 associated deaths.

The cry for a light in the area from the maritime community was

immediate, and with the addition of pressure applied by the Lake Carrierís

Association, Congress passed a resolution approving the establishment of

the new station on February 26, 1907, and quickly followed up with a

$75,000 appropriation for construction on March 4 of that same year

A survey party was dispatched to the area, and selected a 7.63

acre-parcel of land between Two Harbors and Beaver Bay at the upper edge

of a 127-foot tall cliff known locally as Stony Point. While the site

selected for the station was atop Stony Point, for some reason the

Lighthouse Board named the station after Split Rock River, three miles

to the southwest.

Negotiations for purchase of the site began immediately, however

after a year of negotiations, no arrangements were forthcoming.

Evidently the owner had a change of heart after District Engineer Major

Charles Keller instituted condemnation proceedings on the property, and

with clear title in hand late in 1908, Lighthouse Engineer Ralph Russell

Tinkham drew up plans and specifications for the new station. Material

contracts were awarded to a number of suppliers, and the contract for

supplying the 30 to 50 men required to do the actual construction

awarded to L. D. Campbell & Son of Duluth. With the planning phase

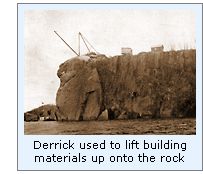

complete, work began at the site in June 1909. With no roads servicing

the area the construction crew was forced to transport all materials to

the site by water. Fortunately, the water depth at the bottom of the

cliff was sufficient to allow vessels to pull close to the cliff face,

and a timber derrick was erected atop the cliff. Outfitted with a

hoisting engine, the derrick was swung out over the cliff face, and all

materials required for construction were hauled to the top. Negotiations for purchase of the site began immediately, however

after a year of negotiations, no arrangements were forthcoming.

Evidently the owner had a change of heart after District Engineer Major

Charles Keller instituted condemnation proceedings on the property, and

with clear title in hand late in 1908, Lighthouse Engineer Ralph Russell

Tinkham drew up plans and specifications for the new station. Material

contracts were awarded to a number of suppliers, and the contract for

supplying the 30 to 50 men required to do the actual construction

awarded to L. D. Campbell & Son of Duluth. With the planning phase

complete, work began at the site in June 1909. With no roads servicing

the area the construction crew was forced to transport all materials to

the site by water. Fortunately, the water depth at the bottom of the

cliff was sufficient to allow vessels to pull close to the cliff face,

and a timber derrick was erected atop the cliff. Outfitted with a

hoisting engine, the derrick was swung out over the cliff face, and all

materials required for construction were hauled to the top.

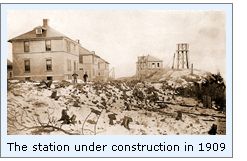

After establishing a working camp atop the cliff, the crew began

blasting foundations for the station buildings. Plans called for the

lighthouse and fog signal building to be erected on a single large

concrete foundation, and the three dwellings to be located in a row to

the north. By July, all of the required construction materials had been

received, and either transported to the site, or in storage at the

Detroit lighthouse depot in readiness for shipment. With winterís icy

grip falling over the north Superior coast, work at the site ended on

November 21, 1909, and the work crews left for home.

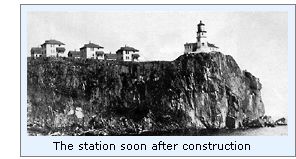

The contractors returned to Spilt Rock on May 1, 1910, and were

elated to find that their work of the previous year had withstood the

rigors of the Lake Superior winter. The new Second Order Fresnel lens

was received at the Detroit lighthouse depot on May 20, and soon

thereafter the lens and the mechanical equipment for the fog signal

building were loaded on the lighthouse tender AMARANTH, and delivered at

the station. The construction crews evidently worked at a feverish pace

over the spring and summer, since by the end of June the fog signal

building was complete, the steel support framework for the tower had

been erected, and work was almost complete on the erection of the three

keepers dwellings. Work was finally brought to completion, and the new

light exhibited for the first time on the night of August 1, 1910. The contractors returned to Spilt Rock on May 1, 1910, and were

elated to find that their work of the previous year had withstood the

rigors of the Lake Superior winter. The new Second Order Fresnel lens

was received at the Detroit lighthouse depot on May 20, and soon

thereafter the lens and the mechanical equipment for the fog signal

building were loaded on the lighthouse tender AMARANTH, and delivered at

the station. The construction crews evidently worked at a feverish pace

over the spring and summer, since by the end of June the fog signal

building was complete, the steel support framework for the tower had

been erected, and work was almost complete on the erection of the three

keepers dwellings. Work was finally brought to completion, and the new

light exhibited for the first time on the night of August 1, 1910.

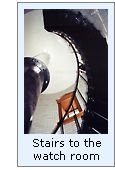

On completion, the lighthouse itself consisted of a pyramidal

octagonal Cream City brick tower with concrete trim atop a concrete

foundation which extended 2 feet six inches into the rock. The tower was

surmounted by a brick watch room and a cast iron lantern with vertical

astragals. Within the tower, a cylindrical glazed white brick lining

housed a set of spiral cast iron steps which provided access to the

watch room and thence to the lantern above. A structural steel framework

sandwiched between the inner and outer walls provided the structure with

the immense strength needed to withstand the heavy wind loads predicted

on the stations lofty perch. A combination cleaning room and office was

attached to north side of the tower by a short passageway.

Seated majestically in the lantern, the Parisian-manufactured

Second

Order Fresnel lens was of "bi-valve" design, so called due to

its resemblance to a mollusk shell. Consisting of two large panels made

up of 7 refracting prisms and 13 reflecting prisms each, the entire

assembly floated on a bed of liquid mercury to minimize rotational

friction. A clockwork mechanism once every 20 seconds, providing the

stationís planned characteristic of a single white flash every 10

seconds. The lens was illuminated by a 55-millimeter double tank

incandescent oil vapor lamp, providing a remarkably bright light of

1,200,000 candlepower. By virtue of the towerís location atop the

cliff, the lens boasted an impressive 168-foot focal plane, and was

visible for a distance of 22 miles in clear weather condition. Seated majestically in the lantern, the Parisian-manufactured

Second

Order Fresnel lens was of "bi-valve" design, so called due to

its resemblance to a mollusk shell. Consisting of two large panels made

up of 7 refracting prisms and 13 reflecting prisms each, the entire

assembly floated on a bed of liquid mercury to minimize rotational

friction. A clockwork mechanism once every 20 seconds, providing the

stationís planned characteristic of a single white flash every 10

seconds. The lens was illuminated by a 55-millimeter double tank

incandescent oil vapor lamp, providing a remarkably bright light of

1,200,000 candlepower. By virtue of the towerís location atop the

cliff, the lens boasted an impressive 168-foot focal plane, and was

visible for a distance of 22 miles in clear weather condition.

Approximately forty feet to the east of the tower, the fog signal was

constructed of the same Cream City brick as the tower. Located on a

single bed within the building, a pair of 22-horsepower gasoline engines

drove two large compressors which supplied compressed air to the

duplicate Type 2-T diaphone fog signals with their large trumpet-shaped

resonators protruding from the lakeward side of the building in order to

project their sound five miles across the lake. The "2-T"

designation for the diaphones indicated that they were of

"two-tone" design, providing the quintessential melancholy

"Bee-Oh" sound every 20 seconds. The fog signal was so loud

that it reportedly made horses skittish five miles away in Beaver Bay,

and caused guests at Slater's Hotel to ask what wild animal were making

such a racket. Approximately forty feet to the east of the tower, the fog signal was

constructed of the same Cream City brick as the tower. Located on a

single bed within the building, a pair of 22-horsepower gasoline engines

drove two large compressors which supplied compressed air to the

duplicate Type 2-T diaphone fog signals with their large trumpet-shaped

resonators protruding from the lakeward side of the building in order to

project their sound five miles across the lake. The "2-T"

designation for the diaphones indicated that they were of

"two-tone" design, providing the quintessential melancholy

"Bee-Oh" sound every 20 seconds. The fog signal was so loud

that it reportedly made horses skittish five miles away in Beaver Bay,

and caused guests at Slater's Hotel to ask what wild animal were making

such a racket.

The three identical brick keepers dwellings sat in a row to the north

of the lighthouse. Each on its own cellar containing a water cistern and

cold storage, their first floors provided a hall, living room, dining

room and kitchen, and their second floors three bedrooms and a bath. A

main concrete walkway lead from the lighthouse in front of the

dwellings, each with its own walkway branching off the main walk at a

crisp 90į angle. Each dwelling was provided

with its own barn across the main walkway for the keeperís horses and

feed.

A log crib pier was erected on a rocky beach area approximately 1,000

feet to the west of the station, with access gained by a long timber

stairway which hugged the rock face at an area where the slope was a

little less severe. A wood framed boat house situated beside the pier

provided storage for the keeperís boats, which the used for

transporting small supplies to the station, and for fishing trips along

the fertile lakeshore. Under a special separate appropriation, a

concrete oil storage building was erected at the station late in 1910,

to allow the storage of kerosene a safe distance from the main station

buildings.

All told, the station was completed for a total cost of $72,541.00,

which was $2,459.00 below the appropriation made three years earlier,

and amazing feat when one considers the logistical problems associated

with construction at such a difficult and remote location. All told, the station was completed for a total cost of $72,541.00,

which was $2,459.00 below the appropriation made three years earlier,

and amazing feat when one considers the logistical problems associated

with construction at such a difficult and remote location.

A seasoned Head Keeper was needed to take charge of the new station,

and Orrin "Pete" Young fit the bill perfectly. Fifty-two years

of age, Young had entered lighthouse service as Second Assistant at

Huron Island in 1901. Promoted to First Assistant in early 1903, he

accepted a transfer to Grand Island East in 1908, in which capacity he

had been serving for the past two years. The offer of a promotion as

Head Keeper of a new first-class coast light station would have been an

enviable offer, and it is no surprise that Young accepted the promotion,

arriving at the new station to take command on July 20, 1910.

First Assistant Keeper Edward F. Sexton had hired in at Devils Island

as Second Assistant in April 1910, and arrived at Split Rock on August

31. With the arrival of Second Assistant Roy C. Gill, the station roster

was complete. Gill had served as Second Assistant at Huron

Island, and

he and Young likely had the opportunity to swap a few stories about

their time the island. In the early days, the station was considered so

remote that it may as well have been located on an island. While the

area around the lighthouse had been clear-cut to ensure a full arc of

visibility of the light, thick virgin forest spread beyond the

lighthouse grounds in all directions. With Lake Superior as the only way

on or off the rock, the stationís mail was delivered to a lumber camp

at the mouth of the Split Rock River, which was considered by Duluthians

to be the eastern extent of civilization on the north shore.

On Sunday October 2, 1910, Assistants Sexton and Gill left the

station at 12.30 p.m. in the stationís small rowboat on such a mail

run. While Keeper Young was understandably concerned when his Assistants

had not returned by nightfall, he was unable to leave the light

unattended until the following morning, when he set out at 8.00 a.m. on

another boat to search for them. He quickly discovered the empty boat

floating bottom-up two miles to the east of the station. Faced with the

realization that that both of his Assistants had likely drowned, Young

searched the area for their bodies to no avail. Needing to return to the

station before dusk to exhibit the light, Young was forced to abandon

the search, and towed the Assistantís boat back to the station. On

returning to the station, Young found the boatís boom had been lashed

to the seat. A consummate sailor, Young knew better than to lash the

boom, since without a keel the rowboat could easily be blown over in a

stiff wind were the boom not allowed to swing free. While Young reported

in the station log book that he searched for the bodies every day for

the following two weeks, they were never found. On Sunday October 2, 1910, Assistants Sexton and Gill left the

station at 12.30 p.m. in the stationís small rowboat on such a mail

run. While Keeper Young was understandably concerned when his Assistants

had not returned by nightfall, he was unable to leave the light

unattended until the following morning, when he set out at 8.00 a.m. on

another boat to search for them. He quickly discovered the empty boat

floating bottom-up two miles to the east of the station. Faced with the

realization that that both of his Assistants had likely drowned, Young

searched the area for their bodies to no avail. Needing to return to the

station before dusk to exhibit the light, Young was forced to abandon

the search, and towed the Assistantís boat back to the station. On

returning to the station, Young found the boatís boom had been lashed

to the seat. A consummate sailor, Young knew better than to lash the

boom, since without a keel the rowboat could easily be blown over in a

stiff wind were the boom not allowed to swing free. While Young reported

in the station log book that he searched for the bodies every day for

the following two weeks, they were never found.

Young sent word to the Detroit office of the death of both of his

Assistants, requesting the appointment of replacements as soon as

possible. Sadly the late First Assistant Sextonís pregnant wife and

young child left the station on October 6 on a motor launch dispatched

to pick them up from Two

Harbors.

Lee Benton was selected as Youngís new First Assistant. A

thirty-two year old with five years experience as Assistant at Devils

Island, Benton reported for duty at Split Rock on October 15. Second

Assistant James W. Taylor, a freshman with only two years of lighthouse

service under his belt at Point Iroquois and Duluth arrived from Duluth

three days behind Benton on the October 18.

After a few years, the derrick used for lifting supplies to the

station proved to be hazardous and cantankerous, and the lighthouse

tender AMARANTH arrived at the station in the fall of 1915 to deliver a

Lighthouse Service engineer and German carpenter and materials to erect

an elevated tramway alongside the stairway leading down to the pier. The

tramway was completely constructed of steel reinforced concrete, poured

into wooden forms erected on site. Supported by concrete trestles, a

pair of iron tracks lead from the water edge to a the top of the bluff.

A small car with flanged wheels and a horizontal upper surface was

pulled up and down the rails by way of a gasoline engine located within

a small hoist house at the top of the bluff. An iron turntable on flat

ground in front of the hoist house allowed the car to be disconnected

from the cable, rotated and switched onto a second set of rails which

lead to the dwellings and oil storage building. The work was completed

in 1916, and the old derrick removed from the cliff top. After a few years, the derrick used for lifting supplies to the

station proved to be hazardous and cantankerous, and the lighthouse

tender AMARANTH arrived at the station in the fall of 1915 to deliver a

Lighthouse Service engineer and German carpenter and materials to erect

an elevated tramway alongside the stairway leading down to the pier. The

tramway was completely constructed of steel reinforced concrete, poured

into wooden forms erected on site. Supported by concrete trestles, a

pair of iron tracks lead from the water edge to a the top of the bluff.

A small car with flanged wheels and a horizontal upper surface was

pulled up and down the rails by way of a gasoline engine located within

a small hoist house at the top of the bluff. An iron turntable on flat

ground in front of the hoist house allowed the car to be disconnected

from the cable, rotated and switched onto a second set of rails which

lead to the dwellings and oil storage building. The work was completed

in 1916, and the old derrick removed from the cliff top.

With the construction of North Shore Highway past the station in

1924, the stationís isolation vanished immediately, as growing numbers

of tourists took the drive from Duluth to visit the station. Light

keepers were mandated to "be courteous and polite to all visitors

and show them everything of interest about the station at such times as

will not interfere with light-house duties." However, it is likely

that in this respect the Split Rock Keepers were challenged highly. In

1936 alone, 30,000 visitors signed the stationís visitor log, and it

is hard to imagine how they were able to keep up with such an influx of

visitors.

With the installation of commercial electric power along the North

Shore Highway in 1941, the station was electrified in 1941. With

electrification, the incandescent oil vapor lamp illuminating the

Fresnel lens was removed, and replaced by an incandescent electric bulb,

with a decrease in intensity of the light to 450,000 candlepower.

Advances in RADAR and LORAN-C rendered the lighthouse obsolete, and

thus the station was closed and the light permanently extinguished in

1969. The Minnesota Historical Society obtained ownership of the

property in 1971, and operates the station as a living museum, with the

structures restored to their pre 1924 appearance. Lee Radzak today

serves as full-time keeper, who along with a number of live-in docents

give tours of the station and presentations on the history of the

station throughout the Great Lakes. Advances in RADAR and LORAN-C rendered the lighthouse obsolete, and

thus the station was closed and the light permanently extinguished in

1969. The Minnesota Historical Society obtained ownership of the

property in 1971, and operates the station as a living museum, with the

structures restored to their pre 1924 appearance. Lee Radzak today

serves as full-time keeper, who along with a number of live-in docents

give tours of the station and presentations on the history of the

station throughout the Great Lakes.

Each year the Lighthouse marks the anniversary of the loss of the

Edmund Fitzgerald with a public program that includes a reading of the

names of the 29 men who lost their lives on the Fitzgerald on November

10th, 1975. The lighthouse, normally closed during the winter, is

reopened for this one day event and the beacon is lighted at dusk.

Hundreds of visitors have attended this event each year since the

ceremony was started in 1985 on the tenth anniversary of the sinking of

"the Big Fitz."

This program provides a once a year opportunity for visitors to be

inside the lighthouse after dark with the beacon again sending its

warning across the dark depths of Lake Superior.

Keepers of

this Light

Click here

to see a complete listing of all Split Rock Light keepers compiled by

Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Seeing this Light

We had been longing to get to see Split Rock since we saw our first

picture a number of years ago, and thus it became the main destination

of our 1999 lighthouse hunting expedition.

It turned-out to be everything we had hoped it would be. We almost

missed our first glimpse of the lighthouse through the trees, about a

mile east of the rock. We made a quick turn around, and pulled off the

road to eat the lunch we bought in Two Harbors with the view as seen in

the photograph to the left.

Driving on, we entered Split Rock Park, and wandered the grounds. The

entire interior of the tower and the attached building is finished in a

shiny white ceramic-coated brick and natural oak woodwork. The entire

complex has been meticulously restored, and costumed docents make

themselves available to answer questions.

One can get down to the water by way of 174 steps, which are located

alongside the old tramway, which was used for pulling supplies to the

light station from a dock on the shore. The view from the Lake is

breathtaking.

The trees on the grounds were laden with berries. and the air was thick

with cedar waxwings which were making a feast of the bright red fruit.

Finding this

Light

Take Hwy 61 Northeast along the shore of Lake Superior through Two

Harbors and on to Split Rock Lighthouse State Park. Keep an eye out for

the view of the lighthouse approximately 1/2 mile West of the park

entrance. The park entrance is on the right, and all roads in the park

are paved. There is plenty of parking, but the lot gets filled quickly

around Holiday weekends. Entrance to the lighthouse and grounds is

gained through the Visitors Center at the rear of the parking area.

Contact

information

Minnesota Historical Society - Split Rock

3713 Split Rock Lighthouse Rd.

Two Harbors, MN 55616

(218) 226-6372

Reference

Sources

Annual reports of the Lighthouse

Board, 1906 - 1909

Annual reports of the Lake Carrier's Association, various, 1908 -

1940

Great Lakes Light List, 1917

Personal visit to Split Rock on 09/05/1999

Keeper listings for this light appear courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|