|

Historical Information

With the planned opening of the new lock at the Soo in 1855, large

vessels would Finally be able to sail directly from Lake Superior to the

lower lakes, and it was evident that the increase in maritime commerce

would be both dramatic and immediate. While the Light at Whitefish Point

served well to guide vessels around the Point after which it was named,

the location of the entrance to the St. Mary's River remained unmarked,

and it was evident that a light was needed to help funnel vessels into

the river mouth at the southeast end of Whitefish Bay. Congress

appropriated $5,000 for the project on March 3, 1853, and a site was

selected for he station that same year at the northern tip of Iroquois

Point. Iroquois Point had received its name in 1662 after the local Ojibwa

encountered a band of intruding Iroquois encamped on the Point. The

following morning both groups were in a full-pitched battle, and by the

end of the day, the entire band of Iroquois had been wiped-out and the

Point named for eternity.

Plans for the station were drawn-up and

arrangements commenced for the purchase of the selected reservation.

Construction began in 1855, and was completed the following year.

Consisting of a 45 foot tall rubble stone tower with a wooden lantern

deck, the tower was outfitted with a flashing white Fourth Order Fresnel

lens. As a result of its location on the highest ground on the Point,

the Light had a 63-foot focal plane, and a range of visibility of 10

nautical miles in clear weather. Little is known about the dwelling at

this station, however it is likely that it too was of rubble stone

construction, and was detached from the tower, as was frequently the

case with such stations built at this time. Charles Caldwell, who had

served for a year as the assistant keeper at Whitefish Point, was

transferred-in as the station's first keeper, and exhibited the light

for the first time on the night of June 8, 1856. Plans for the station were drawn-up and

arrangements commenced for the purchase of the selected reservation.

Construction began in 1855, and was completed the following year.

Consisting of a 45 foot tall rubble stone tower with a wooden lantern

deck, the tower was outfitted with a flashing white Fourth Order Fresnel

lens. As a result of its location on the highest ground on the Point,

the Light had a 63-foot focal plane, and a range of visibility of 10

nautical miles in clear weather. Little is known about the dwelling at

this station, however it is likely that it too was of rubble stone

construction, and was detached from the tower, as was frequently the

case with such stations built at this time. Charles Caldwell, who had

served for a year as the assistant keeper at Whitefish Point, was

transferred-in as the station's first keeper, and exhibited the light

for the first time on the night of June 8, 1856.

It would appear that the materials and

workmanship employed during construction were less than desirable, and

after only twelve years the District Inspector reported that he found

both the tower and dwelling to be in poor condition in 1867, making

special note that the wooden lantern deck on the tower was in danger of

collapse, and needed to be replaced with a more substantial and durable

iron gallery. In his report for the following year, he found the

situation had deteriorated even further, and while he ordered some

necessary repairs, he went on to state that it was his belief that the

only viable remedy for the situation was the complete replacement of

both structures. However, feeling unqualified to make such an expensive

engineering judgment, he recommended that no decision be made until

"the structures are examined by competent persons." It would appear that the materials and

workmanship employed during construction were less than desirable, and

after only twelve years the District Inspector reported that he found

both the tower and dwelling to be in poor condition in 1867, making

special note that the wooden lantern deck on the tower was in danger of

collapse, and needed to be replaced with a more substantial and durable

iron gallery. In his report for the following year, he found the

situation had deteriorated even further, and while he ordered some

necessary repairs, he went on to state that it was his belief that the

only viable remedy for the situation was the complete replacement of

both structures. However, feeling unqualified to make such an expensive

engineering judgment, he recommended that no decision be made until

"the structures are examined by competent persons."

After a visit to the site in 1869, the

Eleventh District Engineer concurred with the Inspectors previous

observations. Finding that the deterioration of both the tower and

dwelling were so advanced that he recommended that no repairs be made

beyond those required to make the buildings habitable until both

buildings could be replaced, since replacement would be more cost

effective than repair in the long run. Estimating that the two new

structures could be built for $18,000, the Lighthouse Board recommended

that Congress make the necessary appropriation in its annual report for

that same year. Congress evidently concurred, since a work party arrived

at Point Iroquois with the necessary materials the following spring, and

worked throughout the season of navigation building the new tower and

dwelling.

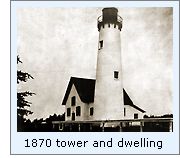

With construction drawing to completion

in the fall of 1870, the new brick tower stood seventeen feet in

diameter at the base, and 50 feet in height from the limestone

foundation to the bottom of the iron gallery. A prefabricated cast iron

spiral stairway with 72 steps wound within the tower, supported by a

hollow central iron column. Capped with a decagonal cast iron lantern

housing the Fourth Order Fresnel from the original tower, exhibiting the

station's characteristic white flash every 30 seconds. The tower's

location atop high ground on the Point provided the lens with a focal

plane of 72 feet, and a resulting 15 mile visible range during clear

weather. The two-story single family brick keepers dwelling was built over a full

basement, and attached to the tower by way of a narrow covered brick

walkway to provide the keeper with welcome shelter as he tended the

light during foul weather. A wood frame barn and brick outhouse

completed the station's complement of buildings. With construction drawing to completion

in the fall of 1870, the new brick tower stood seventeen feet in

diameter at the base, and 50 feet in height from the limestone

foundation to the bottom of the iron gallery. A prefabricated cast iron

spiral stairway with 72 steps wound within the tower, supported by a

hollow central iron column. Capped with a decagonal cast iron lantern

housing the Fourth Order Fresnel from the original tower, exhibiting the

station's characteristic white flash every 30 seconds. The tower's

location atop high ground on the Point provided the lens with a focal

plane of 72 feet, and a resulting 15 mile visible range during clear

weather. The two-story single family brick keepers dwelling was built over a full

basement, and attached to the tower by way of a narrow covered brick

walkway to provide the keeper with welcome shelter as he tended the

light during foul weather. A wood frame barn and brick outhouse

completed the station's complement of buildings.

In order to allow the station to serve

during periods of thick weather, a stand-alone bell tower was erected at

the station in 1885, with the bell struck by a Stevens automatic bell

striking apparatus. However, the bell was not destined to serve long at

Iroquois Point, since plans were drawn up to replace it with a pair of

10-inch steam whistles in early 1890. Contracts for the materials for

the new fog signal building and machinery were awarded, and the

materials delivered to the Detroit lighthouse depot by the supplying

contractors. The materials were then loaded onto the lighthouse tender

AMARANTH along with a work party and transported up Lake Huron and

through the Soo lock to Point Iroquois. Construction of the new fog

signal building, and the installation of the steam power plants and

whistles was completed that fall. The whistle controls were adjusted to

ensure that the whistles conformed to the station's prescribed repeated

characteristic of a five-second blast followed my twenty-five seconds of

silence, and the new signal was officially placed into service on

October 31, 1890. With a significant increase in the workload

represented by the new fog signal, James Lasley Jr. was appointed to the

position of acting assistant keeper on November 20, moving into the

cramped dwelling with head keeper Edward Chambers and his family. In order to allow the station to serve

during periods of thick weather, a stand-alone bell tower was erected at

the station in 1885, with the bell struck by a Stevens automatic bell

striking apparatus. However, the bell was not destined to serve long at

Iroquois Point, since plans were drawn up to replace it with a pair of

10-inch steam whistles in early 1890. Contracts for the materials for

the new fog signal building and machinery were awarded, and the

materials delivered to the Detroit lighthouse depot by the supplying

contractors. The materials were then loaded onto the lighthouse tender

AMARANTH along with a work party and transported up Lake Huron and

through the Soo lock to Point Iroquois. Construction of the new fog

signal building, and the installation of the steam power plants and

whistles was completed that fall. The whistle controls were adjusted to

ensure that the whistles conformed to the station's prescribed repeated

characteristic of a five-second blast followed my twenty-five seconds of

silence, and the new signal was officially placed into service on

October 31, 1890. With a significant increase in the workload

represented by the new fog signal, James Lasley Jr. was appointed to the

position of acting assistant keeper on November 20, moving into the

cramped dwelling with head keeper Edward Chambers and his family.

Since the construction of the new

station, lamp oil had been stored in a room designated for the purpose

in the basement. This had been a wholly acceptable practice when whale

oil was used as the primary illuminant, since it was not particularly

volatile. However, with the conversion to the more flammable kerosene, a

number of fires were experienced in dwellings around the country, and

the Lighthouse Board embarked on a project to install stand-alone

fireproof oil storage buildings at all stations throughout the system.

To this end, a circular prefabricated iron oil storage building was

shipped to the station, and erected a safe distance from the dwelling in

1893. No longer serving any purpose, the bell tower was disassembled in

1896, loaded on the lighthouse tender AMARANTH and shipped to Grand

Marais, where it's mechanism was in the Front Range Light currently

under construction. The following year, 448 feet of new concrete

walkways were poured to link the various station buildings, and the

landing dock was rebuilt. Since the construction of the new

station, lamp oil had been stored in a room designated for the purpose

in the basement. This had been a wholly acceptable practice when whale

oil was used as the primary illuminant, since it was not particularly

volatile. However, with the conversion to the more flammable kerosene, a

number of fires were experienced in dwellings around the country, and

the Lighthouse Board embarked on a project to install stand-alone

fireproof oil storage buildings at all stations throughout the system.

To this end, a circular prefabricated iron oil storage building was

shipped to the station, and erected a safe distance from the dwelling in

1893. No longer serving any purpose, the bell tower was disassembled in

1896, loaded on the lighthouse tender AMARANTH and shipped to Grand

Marais, where it's mechanism was in the Front Range Light currently

under construction. The following year, 448 feet of new concrete

walkways were poured to link the various station buildings, and the

landing dock was rebuilt.

1900 saw the replacement of the iron

smoke stacks on the fog signal with brick chimneys, both boilers were

re-tubed and the barn was replaced. The crew returned the following

year, painted the barn, sunk a new well and installed 550 feet of wire

fencing. No doubt 1901 was also a memorable year for keeper Joseph

Bishop and his assistant Otto Bufe, since they were kept busy feeding 28

tons of coal into the hungry fog signal boilers in order to keep the

whistles screaming for a total of 534 hours, an all-time record for the

station.

In 1902, Eleventh District Inspector

Commander Edward H. Gheen finally took up the interests of the Point

Iroquois keepers and their families, who had been shoe-horned into the

single family dwelling since the first assistant was assigned to the

station after the fog signal was added in 1890. Estimating that a second

dwelling could be erected for a cost of $5,000, the Lighthouse Board

requested that the necessary appropriation be made in its annual report

for that year. Congress turned a deaf ear to the Board's repeated

requests for three years until 1905, when the funds were finally

approved, and work could proceed. However, rather than building a

separate structure as was originally planned, the decision was made to

expand the existing structure through the addition of a new wing on the

east side of the existing dwelling. A new boathouse was also built and

600 feet of new concrete walks were laid, with the work reaching

completion on November 11, 1905. In 1902, Eleventh District Inspector

Commander Edward H. Gheen finally took up the interests of the Point

Iroquois keepers and their families, who had been shoe-horned into the

single family dwelling since the first assistant was assigned to the

station after the fog signal was added in 1890. Estimating that a second

dwelling could be erected for a cost of $5,000, the Lighthouse Board

requested that the necessary appropriation be made in its annual report

for that year. Congress turned a deaf ear to the Board's repeated

requests for three years until 1905, when the funds were finally

approved, and work could proceed. However, rather than building a

separate structure as was originally planned, the decision was made to

expand the existing structure through the addition of a new wing on the

east side of the existing dwelling. A new boathouse was also built and

600 feet of new concrete walks were laid, with the work reaching

completion on November 11, 1905.

The station's illuminating apparatus

was upgraded from oil wick to incandescent oil vapor on May 3, 1913,

with a resulting increase in intensity from 5,600 candlepower to 42,000

candlepower. At the same time, the characteristic of the light was

changed by decreasing the duration of the light's flash to 6.7 seconds

with a corresponding increase in the duration of the eclipse. Not

content with this change, the characteristic was again modified on June

13, 1922 by a further reduction of the light's cycle to only 4 seconds,

with a flash of only 0.8 seconds duration. The station's illuminating apparatus

was upgraded from oil wick to incandescent oil vapor on May 3, 1913,

with a resulting increase in intensity from 5,600 candlepower to 42,000

candlepower. At the same time, the characteristic of the light was

changed by decreasing the duration of the light's flash to 6.7 seconds

with a corresponding increase in the duration of the eclipse. Not

content with this change, the characteristic was again modified on June

13, 1922 by a further reduction of the light's cycle to only 4 seconds,

with a flash of only 0.8 seconds duration.

The 10-inch steam whistles were removed

from the fog signal building in 1926, and replaced with a pair of air

compressed air operated Type F diaphone

fog signals. Twin diesel-powered

electrical generators were installed in the fog signal building to

provide power for the compressors, and the fog signal characteristic was

changed to a repeated cycle consisting of a 2-second blast followed by

28 seconds of silence. The diaphones represented a considerable

improvement over the steam whistles, since they were not only louder and

easier to maintain, but could be quickly sounded when needed, without

having to wait for boilers to build up a head of steam. With the

installation of the electrical generators, power was run to the dwelling

and the lamp itself, which was replaced with an incandescent electric

bulb which boosted the intensity of the light to an impressive 82,000

candlepower. The 10-inch steam whistles were removed

from the fog signal building in 1926, and replaced with a pair of air

compressed air operated Type F diaphone

fog signals. Twin diesel-powered

electrical generators were installed in the fog signal building to

provide power for the compressors, and the fog signal characteristic was

changed to a repeated cycle consisting of a 2-second blast followed by

28 seconds of silence. The diaphones represented a considerable

improvement over the steam whistles, since they were not only louder and

easier to maintain, but could be quickly sounded when needed, without

having to wait for boilers to build up a head of steam. With the

installation of the electrical generators, power was run to the dwelling

and the lamp itself, which was replaced with an incandescent electric

bulb which boosted the intensity of the light to an impressive 82,000

candlepower.

With improvements in RADAR, radio

navigation and LORAN-C in the late 1950's many of the nation's lights

quickly became obsolete. After Point Iroquois Lighted Buoy 44 was

installed offshore in 1962, the Point Iroquois Light was discontinued.

In an event to reduce operating costs, the Coast Guard transferred

ownership of the station to the U. S. Park Service in 1965, with the

property incorporated into the Hiawatha National Forest. No longer

serving any purpose, the station's Fourth Order Fresnel was removed from

the lantern later that year after more than a century of faithful

service to lake Superior mariners. The lens was carefully disassembled

and crated-up, and shipped to Washington DC, where it was placed on

display at the Smithsonian Institution. With improvements in RADAR, radio

navigation and LORAN-C in the late 1950's many of the nation's lights

quickly became obsolete. After Point Iroquois Lighted Buoy 44 was

installed offshore in 1962, the Point Iroquois Light was discontinued.

In an event to reduce operating costs, the Coast Guard transferred

ownership of the station to the U. S. Park Service in 1965, with the

property incorporated into the Hiawatha National Forest. No longer

serving any purpose, the station's Fourth Order Fresnel was removed from

the lantern later that year after more than a century of faithful

service to lake Superior mariners. The lens was carefully disassembled

and crated-up, and shipped to Washington DC, where it was placed on

display at the Smithsonian Institution.

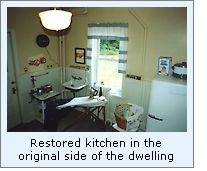

The station buildings were thereafter

leased to the Bay Mills-Brimley Historical Research Society, which

completed a total restoration of the building in 1983. Much of the

station has been converted into an excellent maritime museum, and is

open to visitors from Memorial Day through October 15, and is well worth

visiting.

Keepers of this

Light

Click here

to see a complete listing of all Point Iroquois Light keepers compiled

by Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Seeing this Light

We arrived at Point Iroquois at 4.00pm,

just before the main building, of which approximately 50% has been

carefully restored, was closing for the day.

There is an excellent display of contemporary photographs of the

families that called the station home through the years. The display is

one of the most interesting that we have encountered, and serves well to

bring the former inhabitants to life. if only for the moment.

At the time of our visit, the entire exterior was being painted, and as

a result the tower was not open to the public. It

took some doing to find vantage points in which scaffolding did not ruin

the view!

Finding this Light

Take M221 into Brimley and turn left onto 6 Mile Rd. Continue on 6 Mile

Rd. to the lighthouse grounds. Since the lighthouse is part of the

Hiawatha National Forest, there is plenty of parking available. Take M221 into Brimley and turn left onto 6 Mile Rd. Continue on 6 Mile

Rd. to the lighthouse grounds. Since the lighthouse is part of the

Hiawatha National Forest, there is plenty of parking available.

The museum and tower are open to the public every day from Memorial Day

through October 15. Hours are 10.00am to 5.00pm, seven days a week. On

Friday, Saturday and Sunday, they reopen from 7.00pm to 9.00pm.

Contact

information

Point Iroquois Lighthouse & Maritime Museum

Sault Ste. Marie Ranger Office

4000 I-75 Business Spur

Sault Ste. Marie, MI 49783

(906) 635-5311 or (906) 437-5272

Reference Sources

Inventory of Historic Light Stations,

National Parks Service,

1994.

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Board, various, 1853-1909

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Service, various, 1910-1939

Annual reports of the Lake Carrier's Association, various,

1906-1940

Rites of Conquest, Charles E. Cleland, 1992

Email from Russ Rowlett, 06/01/2000

Personal

visits to Point Iroquois on 09/09/1998 & 07/21/2002

Historical photographs courtesy of the Point Iroquois Lighthouse &

Maritime Museum

Aerial photograph courtesy of Marge Beaver of Photography

Plus

Photographs from author's personal collection.

Keeper listings for this light appear courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|