|

Historical Information

Isle Royale lies out in Lake Superior some sixty miles to the north of

the Keweenaw peninsula, and a scant 14 miles south of the Canadian north

shore. It would be natural to assume that an island located so close to

the Canadian shore would be Canadian territory. However, during border

negotiations between the British and the nascent United States at the

Treaty of Paris in 1783, misunderstandings resulting from a lack of

accurate maps of the area caused the island to be included as part of

United States territory. While a number of Scandinavian fishermen would

set up operations on the island in the early 1800's, and John Jacob

Astor's American Fur Company would establish a trading post here in

1837, it would not be until the late 1840's that the United States

government would realize the windfall that resulted from the 1783

cartographic misunderstanding.

With the discovery of copper on the

island in 1843, two separate mining camps were established, one in

Siskiwit Bay on the southeastern end of the island and the other at Rock

Harbor to the north. To serve vessels seeking to load copper at the

latter, the Rock Harbor Light was established at the entrance to the

harbor in 1855. Unfortunately, simultaneous to the establishment of the

light, the copper boom on the island ended, and the Light was

extinguished and the station discontinued and abandoned in 1859 With the discovery of copper on the

island in 1843, two separate mining camps were established, one in

Siskiwit Bay on the southeastern end of the island and the other at Rock

Harbor to the north. To serve vessels seeking to load copper at the

latter, the Rock Harbor Light was established at the entrance to the

harbor in 1855. Unfortunately, simultaneous to the establishment of the

light, the copper boom on the island ended, and the Light was

extinguished and the station discontinued and abandoned in 1859

With the outbreak of the Civil War, and

a resulting increase in metals consumption, miners once again set their

sights on Isle Royale, and new and more efficient mines were established

at Siskiwit Bay on the southeast shore and McCargo Cove on the

northwest. Thriving communities grew up around these mines to support

the mining and shipment of copper, and with a resurgence in maritime

traffic making for the island to transport copper south through the

Sault Locks, the old Rock Harbor Light was reactivated in August, 1874.

Realizing that Rock Harbor Light served

only traffic passing close to the harbor for which it was named, the

Lighthouse Board recommended that $20,000 be appropriated to construct

an additional lighthouse in the area in its 1872 annual report. While

Congress responded with the appropriation on March 3, 1873, the Board

was undecided as to the best location for the new station in order to

provide the greatest benefit. After considering a number of

alternatives, the decision was finally made in 1874 to locate the new

station on Menagerie Island, the most easterly of the group of small

islands at the opening of Siskiwit Bay. However, with winter beginning

to seize Superior in its icy grip, work on the island was not scheduled

to commence until the opening of the 1875 navigation season. Eleventh

District Engineer Major Godfrey Weitzel's plans for the station called

for both the tower and dwelling to be built of stone, and thus an order

was placed with the Jacobsville sandstone quarry, approximately 80 miles

south of Menagerie on the Keweenaw Peninsula, to reduce the cost of

transporting such heavy materials all the way from the Detroit depot. Realizing that Rock Harbor Light served

only traffic passing close to the harbor for which it was named, the

Lighthouse Board recommended that $20,000 be appropriated to construct

an additional lighthouse in the area in its 1872 annual report. While

Congress responded with the appropriation on March 3, 1873, the Board

was undecided as to the best location for the new station in order to

provide the greatest benefit. After considering a number of

alternatives, the decision was finally made in 1874 to locate the new

station on Menagerie Island, the most easterly of the group of small

islands at the opening of Siskiwit Bay. However, with winter beginning

to seize Superior in its icy grip, work on the island was not scheduled

to commence until the opening of the 1875 navigation season. Eleventh

District Engineer Major Godfrey Weitzel's plans for the station called

for both the tower and dwelling to be built of stone, and thus an order

was placed with the Jacobsville sandstone quarry, approximately 80 miles

south of Menagerie on the Keweenaw Peninsula, to reduce the cost of

transporting such heavy materials all the way from the Detroit depot.

The Lighthouse tender DAHLIA anchored

off Menagerie Island in the spring of 1875 and unloaded a working party

and all of the materials for construction with the exception of the

stone. While the working party busied itself building temporary living

quarters, a dock, and in blasting foundations for the tower and

dwelling, DAHLIA set sail for Jacobsville to load the stone quarried

over the winter. After returning to Menagerie Island and unloading the

stone, the tender departed, leaving the working party to continue

construction.

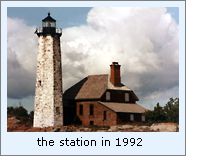

Over that summer the four buildings

which comprise the station took shape. The 61' tall sandstone tower was

constructed with double walls to provide stability, provide an air space

within the wall to reduce interior moisture, and to provide a

cylindrical inner support for the cast iron spiral staircase. Standing

16' in diameter at the base, the tower's exterior walls tapered gently

to diameter of 10' beneath the gallery. Supported by twin corbels on

each of its eight sides, the cast iron gallery assembled atop the tower

and outfitted with a tubular iron safety railing. At the gallery's

center, the prefabricated cast iron octagonal lantern was erected, and

the fixed white Fourth Order

Fresnel lens placed atop a cast iron pedestal. By virtue of the

tower's location on a high point on the island, the lens was situated at

a focal plane of 74 feet and was visible for a distance of 15 ½ miles.

On completion, the tower was whitewashed and the lantern and gallery

painted black to help the structure to serve as a more effective

daymark. The 1 ½-story dwelling was constructed of unpainted sandstone

and featured a gabled roof with partial hips at each gable end. The

dwelling was connected to the tower by way of an 8 foot long covered passageway

to provide protection for the keepers making their frequent trips to the

tower in inclement weather. With completion of a wooden storage shed and

a brick privy, work on the island was completed on September 20, 1875.

William Stevens was appointed as Acting Keeper for the station, and with

his wife appointed as Acting First Assistant, the couple arrived on the

island and moved their worldly belongings into the new dwelling in time

to exhibit the new light for the first time on the evening of October

19, 1875. Over that summer the four buildings

which comprise the station took shape. The 61' tall sandstone tower was

constructed with double walls to provide stability, provide an air space

within the wall to reduce interior moisture, and to provide a

cylindrical inner support for the cast iron spiral staircase. Standing

16' in diameter at the base, the tower's exterior walls tapered gently

to diameter of 10' beneath the gallery. Supported by twin corbels on

each of its eight sides, the cast iron gallery assembled atop the tower

and outfitted with a tubular iron safety railing. At the gallery's

center, the prefabricated cast iron octagonal lantern was erected, and

the fixed white Fourth Order

Fresnel lens placed atop a cast iron pedestal. By virtue of the

tower's location on a high point on the island, the lens was situated at

a focal plane of 74 feet and was visible for a distance of 15 ½ miles.

On completion, the tower was whitewashed and the lantern and gallery

painted black to help the structure to serve as a more effective

daymark. The 1 ½-story dwelling was constructed of unpainted sandstone

and featured a gabled roof with partial hips at each gable end. The

dwelling was connected to the tower by way of an 8 foot long covered passageway

to provide protection for the keepers making their frequent trips to the

tower in inclement weather. With completion of a wooden storage shed and

a brick privy, work on the island was completed on September 20, 1875.

William Stevens was appointed as Acting Keeper for the station, and with

his wife appointed as Acting First Assistant, the couple arrived on the

island and moved their worldly belongings into the new dwelling in time

to exhibit the new light for the first time on the evening of October

19, 1875.

The difficult conditions on the island

can be clearly felt from William's entry in the station log book on Oct.

26 1875, when he wrote "Damp and cloudy. The East northeast gale

increased almost to hurricane. At 6 AM the sea went clear over tower,

rocks and broke the window sashes on south side of the house. Washed

away everything loose, lumber, wood, rocks off the island." The

Williams' both received permanent appointments on November 18, 1876,

however their time on the island was not to be long-lived, as William

accepted a transfer to the less exposed and confining Portage Lake Ship

Canal Light on August 9, 1878.

John H Malone was appointed to replace

Williams, and unlike his predecessor, chose not to have his wife serve

in any official capacity at the station, instead arranging for his

brother James to take the Assistant position. While life on Menagerie

Island was far from luxurious, it must have suited John and his wife

well, as they would end up staying on the island a remarkable thirty-two

years, raising twelve children in the shadow of the Menagerie Island

Light. Although a number of sources have reported that Menagerie Island

received its name for Malone's "menagerie" of children, this

appears to be pure fancy. Official government documents reporting on the

site chosen for the station in 1872 made specific reference to

"Menagerie Island." and since the Malones did not arrive on

the island until August 1878, the name was evidently in common use at

least six years in advance of their arrival, and long before their

family would have reached a number that could have been considered a

"menagerie." However, the size of their family is a matter of

record, and one can only imagine the trials faced by John and his wife

in raising and educating twelve children on such a small, barren island.

When considering the storms that ravaged the island, the fact that none

of the children ended up drowning in Superior's frigid waters is in

itself amazing. In one such storm on October 1, 1884, Malone's log entry

recorded that waves smashed over the island with such ferocity that the

boathouse and ways were completely ripped from their foundations and

carried away. John H Malone was appointed to replace

Williams, and unlike his predecessor, chose not to have his wife serve

in any official capacity at the station, instead arranging for his

brother James to take the Assistant position. While life on Menagerie

Island was far from luxurious, it must have suited John and his wife

well, as they would end up staying on the island a remarkable thirty-two

years, raising twelve children in the shadow of the Menagerie Island

Light. Although a number of sources have reported that Menagerie Island

received its name for Malone's "menagerie" of children, this

appears to be pure fancy. Official government documents reporting on the

site chosen for the station in 1872 made specific reference to

"Menagerie Island." and since the Malones did not arrive on

the island until August 1878, the name was evidently in common use at

least six years in advance of their arrival, and long before their

family would have reached a number that could have been considered a

"menagerie." However, the size of their family is a matter of

record, and one can only imagine the trials faced by John and his wife

in raising and educating twelve children on such a small, barren island.

When considering the storms that ravaged the island, the fact that none

of the children ended up drowning in Superior's frigid waters is in

itself amazing. In one such storm on October 1, 1884, Malone's log entry

recorded that waves smashed over the island with such ferocity that the

boathouse and ways were completely ripped from their foundations and

carried away.

In a violent storm on November 7, 1885,

the two year old Canadian Pacific luxury passenger propeller ALGOMA lost

control in the lake, and was blown aground on Greenstone Island off Rock

Harbor. Malone made note of the disaster in his log after learning of

the accident on the 9th, a few days before closing the station for the

season. On his return to reopen the station on May 12, 1886, reminders

of the wreck were evidently still visible in the area, as he noted in

the station log that "Indian boats pass with loads of furniture

from ALGOMA - chairs, lounges, bedsprings and feather pillows."

and seven days later, he recorded that "lifejackets, pillos

(sic), parts of a piano" were washing up along Menageries rocky

shore. 1886 was also the year in which John's brother George accepted a

promotion as Acting Keeper at the Minnesota Point Light on October 2,

1886, and was replaced by George Genry on the opening of the 1887

navigation season.

The Malones had to be resourceful to

supplement the supplies left by the lighthouse tender during the

District Inspector's infrequent visits to the station. They planted a

small garden in the sparse soil on the Menagerie, and managed to

successfully grew lettuce and radishes. They also maintained a potato

patch on nearby Wright Island, where the soil cover was considerably

deeper. Frequent mention was also made in the log books of fishing,

trapping, hunting rabbits and ducks, and the collecting of seagull eggs.

While seagull eggs might not sound appealing to our tastes of today,

they apparently constituted a considerable part of the family's diet.

They also appear to have represented some "trading value" with

the outside world, as Malone's log entry for June 1, 1887 stated that he

had "collected 1,478 gull eggs to date - 32 eggs blowed out for

supply vessel crew." What he might have traded for the eggs is

an interesting matter for speculation, and will likely never come to

light. The Malones had to be resourceful to

supplement the supplies left by the lighthouse tender during the

District Inspector's infrequent visits to the station. They planted a

small garden in the sparse soil on the Menagerie, and managed to

successfully grew lettuce and radishes. They also maintained a potato

patch on nearby Wright Island, where the soil cover was considerably

deeper. Frequent mention was also made in the log books of fishing,

trapping, hunting rabbits and ducks, and the collecting of seagull eggs.

While seagull eggs might not sound appealing to our tastes of today,

they apparently constituted a considerable part of the family's diet.

They also appear to have represented some "trading value" with

the outside world, as Malone's log entry for June 1, 1887 stated that he

had "collected 1,478 gull eggs to date - 32 eggs blowed out for

supply vessel crew." What he might have traded for the eggs is

an interesting matter for speculation, and will likely never come to

light.

As was the case with the keepers

assigned to most of Superior's offshore lights, the Malones only lived

on the island during the navigation season, spending their winters in

Duluth. Under normal circumstances, one of the lighthouse tenders was

expected to take them out to the island in early May with the

disappearance of most of the lake ice, and then return to retrieve them

in mid November before the ice grew too thick to allow the vessels to

penetrate However, life on Menagerie was far from normal, and in those

frequent situations in which the tenders were unavailable, Malone was

left to his own devices to make his way to and from the island. In his

first entry in the station log for 1889, Malone documented the harrowing

and circuitous journey he took to get out to his station that year as

follows: As was the case with the keepers

assigned to most of Superior's offshore lights, the Malones only lived

on the island during the navigation season, spending their winters in

Duluth. Under normal circumstances, one of the lighthouse tenders was

expected to take them out to the island in early May with the

disappearance of most of the lake ice, and then return to retrieve them

in mid November before the ice grew too thick to allow the vessels to

penetrate However, life on Menagerie was far from normal, and in those

frequent situations in which the tenders were unavailable, Malone was

left to his own devices to make his way to and from the island. In his

first entry in the station log for 1889, Malone documented the harrowing

and circuitous journey he took to get out to his station that year as

follows:

"April 30, 1889. Arrived at

this station today, had quite a hard trip. Left Duluth April 22nd per

Steamer Ossigridge. Layed-over Two Harbors due to nor'easter. Left Two

Harbors on 23rd for Grand Marais. Stayed till 25th. Snowed 4 inches.

Left Grand Marais 25th, arrived at Washington Harbor 8:20 AM on 26th.

Left Washington Harbor 11:30 per Brower tug, and arrived at Tobin's

Harbor at 6:20 PM. Left Tobin's Harbor 10:20 AM the 27th, and arrived at

Wright's Island abreast of lighthouse. Stayed until 2:10 PM April 30th.

6 inches snow fell. Arrived at crib at 3:20 in tail end of gale. Water

had dropped 14 inches. We got our provisions and selves all wet. Had to

buy a boat at Tobin's Harbor as water too low to launch lighthouse boat.

We found station dry and in good shape. Lighted the lamp."

Not surprisingly, after being born and

raised on the island, lighthouse keeping was in the blood of the Malone

family. When First Assistant Alexander McLean was promoted to the

position of Keeper of the Eagle Harbor Ranges on January 15, 1900, one

of Malone's sons John A Malone took over as the station's First

Assistant under the watchful tutelage of his father.

Prior to the 1890's, lamp oil had been

stored in storage rooms within the dwellings at almost all US light

stations. As a result of a number of fires from the increasingly

volatile kerosene being used, a system-wide project of erecting separate

oil storage buildings some distant from the dwellings was undertaken in

the early 1890's. Perhaps indicating the low position in which the

Menagerie Island Light was held in the greater scheme of things by the

Eleventh District office, the island was one of the last stations in the

district to be outfitted with such an oil storage shed in 1906, when a

work crew arrived with materials to construct a concrete 500 gallon

capacity storage building. Prior to the 1890's, lamp oil had been

stored in storage rooms within the dwellings at almost all US light

stations. As a result of a number of fires from the increasingly

volatile kerosene being used, a system-wide project of erecting separate

oil storage buildings some distant from the dwellings was undertaken in

the early 1890's. Perhaps indicating the low position in which the

Menagerie Island Light was held in the greater scheme of things by the

Eleventh District office, the island was one of the last stations in the

district to be outfitted with such an oil storage shed in 1906, when a

work crew arrived with materials to construct a concrete 500 gallon

capacity storage building.

Perhaps growing weary of life on the

small island, John H Malone accepted a transfer to Pipe Island after an

incredible 32 years as keeper of the Menagerie Island Lighthouse.

However, the Malone name was not to disappear from the payroll records

of the station, as First Assistant Keeper John A Malone was promoted to

the position of Keeper on his fathers departure for Pipe Island on

October 12, 1910

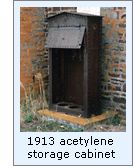

By the end of the first decade of the

new century, the copper mines on Isle Royale had all ceased operations

and maritime traffic in the area dwindled to virtually nothing, and in

order to reduce costs, the gears were turning at the Detroit office to

automate the Menagerie Island Light. In 1913, a work crew arrived at the

station and installed an acetylene lighting system equipped with an

automatic sun valve. With an iron vault containing three acetylene

cylinders located on an exterior wall of the dwelling, sufficient

acetylene was available to keep the light burning for the entire season

without refilling. With automation, the constant attention of keepers at

the station was no longer deemed a necessity, and John A Malone resigned

from lighthouse service and left the island, thus ending a remarkable 38

year association of the Malone name with the Menagerie Island Light.

October 29, 1915 saw a change in the

characteristic of the acetylene light to show a white half-second flash

every 5 seconds. Other than annual trips to refill the acetylene tanks

and to troubleshoot problems with the light reported by mariners, things

on the island stayed unchanged until 1941, when the acetylene system was

replaced by a battery powered lighting system. This battery system was

finally removed in 1993, and replaced with a 12 volt solar powered 300

mm Tidelands Signal acrylic optic with automatic bulb changer, which can still be seen

casting its light ten miles into the darkness to this day.

Keepers of this

Light

Click here

to see a complete listing of all Menagerie Island Light keepers compiled by

Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes Lighthouse Research.

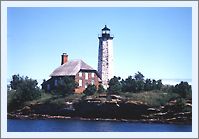

Finding this Light

The Voyageur

II, a 60' aluminum diesel cruiser transports mail and passengers

to Isle Royale. The vessel leaves Grand Portage, Minnesota and travels

clockwise around the park, staying overnight at Rock Harbor. Along the

way, it passes close to Menagerie Island, and photographs of the

lighthouse should be possible with a telephoto lens of around 500 mm

focal length (10x digital.)

For close-up views of the lighthouse, a

private boat or a charter boat out of Grand Portage would likely provide

the best opportunities.

Keweenaw Excursions also offers a

lighthouse cruise which passes Menagerie Island on board the KEWEENAW

STAR out of Houghton, Michigan. For more information on any of their

tours visit their website,

or telephone Keweenaw Excursions at (906) 482-0884.

Reference Sources

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Board, various, 1878 - 1909

Annual report of the Lake Carrier's Association, 1915

Great Lakes Light Lists, various, 1901 - 1997

Log books of the Menagerie Island Light, transcribed by Don

Nelson.

Northern Lights, Charles K. Hyde

Email correspondence with Don Nelson, various, 2002

Photographs of the station courtesy of Don Nelson & Wayne Sapulski.

Isle Royale National Park, foot trails & water routes, Kim

DuFresne, 1984

Keeper listings for this light appear courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|