|

Historical

Information

As was the case with most areas along the shores of the

Great Lakes, Sturgeon Bay gained its initial prosperity through the

lumbering of the seemingly endless forests that surround the lake.

However, with the declining availability of lumber resulting from

clear-cutting, the area was under a metamorphosis as a shipbuilding

center. With vessels required to sail completely around the peninsula

and through Death's Door to make entry into the port of Green Bay and

the boatyards in Sturgeon Bay, a group of local business interests under

the urging of Joseph Harris, Sr. the editor of the Door County Advocate,

conceived the idea of excavating a canal through the swampy ground

between Lake Michigan and Sturgeon Bay to drastically shorten the route

of navigation. The Sturgeon Bay and Lake Michigan Ship Canal and Harbor

Company was formed, shares were sold and excavation began in 1872.

By 1880, work had progressed to the point that small

vessels were able to negotiate the new cut, and with opening for larger

vessels planned for 1882, the Company realized that an aid to navigation

was needed to guide vessels into the western end of the waterway. An

agreement was reached with the Lighthouse Board whereby the Board agreed

to establish a light station if the company would purchase the necessary

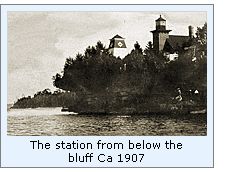

land and deed it over to the Federal Government. In March 1880, a site

atop a thirty-foot limestone bluff known as Sherwood Point was selected

for the station, a 1.1-acre site surveyed, and negotiations were

underway to obtain clear title for the site. While Congress appropriated

the $12,000 for the station's construction on March 31, 188, the matter

of title to the site was not resolved until 188, and thus construction

did not begin until May 14, when the lighthouse tender WARRINGTON

anchored off Sawyers Harbor as a working party of 20 men labored to

lighter all of the building materials to shore. By 1880, work had progressed to the point that small

vessels were able to negotiate the new cut, and with opening for larger

vessels planned for 1882, the Company realized that an aid to navigation

was needed to guide vessels into the western end of the waterway. An

agreement was reached with the Lighthouse Board whereby the Board agreed

to establish a light station if the company would purchase the necessary

land and deed it over to the Federal Government. In March 1880, a site

atop a thirty-foot limestone bluff known as Sherwood Point was selected

for the station, a 1.1-acre site surveyed, and negotiations were

underway to obtain clear title for the site. While Congress appropriated

the $12,000 for the station's construction on March 31, 188, the matter

of title to the site was not resolved until 188, and thus construction

did not begin until May 14, when the lighthouse tender WARRINGTON

anchored off Sawyers Harbor as a working party of 20 men labored to

lighter all of the building materials to shore.

After clearing and grading a road from Sawyers Harbor

to the station site, the building materials and supplies were

transported to the work site by team, and work began in earnest. A

cellar was blasted into the rock, which the masons lined with rubble

stone gleaned from the site after the blasting process. Beneath what

would end up being the kitchen end of the cellar, a 1,500-gallon brick

cistern was erected to hold drinking water, its interior surfaces lined

with a plaster coating. By June 30, four courses of red brick had been

laid atop the rubble stone foundation walls, a brick-lined drain had

been laid leading from the cellar to the bluff face, and a 4"

diameter well had been drilled through the rock to a depth of 42 feet,

and piped into the cistern in the cellar. After clearing and grading a road from Sawyers Harbor

to the station site, the building materials and supplies were

transported to the work site by team, and work began in earnest. A

cellar was blasted into the rock, which the masons lined with rubble

stone gleaned from the site after the blasting process. Beneath what

would end up being the kitchen end of the cellar, a 1,500-gallon brick

cistern was erected to hold drinking water, its interior surfaces lined

with a plaster coating. By June 30, four courses of red brick had been

laid atop the rubble stone foundation walls, a brick-lined drain had

been laid leading from the cellar to the bluff face, and a 4"

diameter well had been drilled through the rock to a depth of 42 feet,

and piped into the cistern in the cellar.

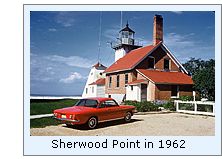

The structure that took shape over the remainder of

the summer was the first of a design that would be duplicated the

following year at Little Traverse and Baraga. Taking the form of a two

and a half story red brick dwelling containing six rooms with a square

tower 8' 5" in plan with walls 12" in thickness integrated

into the center of the north gable end. A double flight of wooden stairs

within the tower lead from the first floor to an open landing on the

second floor, and served as the only connection between the two floors.

To tower was capped with a square cast iron gallery floor, on which a

decagonal prefabricated cast iron lantern seven feet in diameter was

centered. Access to the lantern was provided by a steep set of stairs

leading from the second floor landing to a scuttle in the lantern floor

equipped with a cast iron door. The lantern was in turn capped by a roof

consisting of ten prefabricated cast iron sections, and crowned with a

cast iron ventilator ball with a brass lightning spike tipped with

platinum. A ¾" diameter wrought iron lightning conductor was

attached to the lower side of the iron lantern deck, and lead down the

exterior of the brick tower through I bolts to a ground rod sunk into

the bedrock twelve feet away from the tower. Bolted to the center of the

lantern floor, a cast iron pedestal served as a mounting base for the

station's illuminating apparatus.

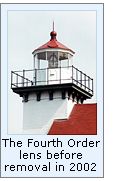

The district Lampist, Mr. Crump, arrived at the

station, and carefully uncrated the station's new Fourth

Order Fresnel lens which had been manufactured in France and

shipped to the station by way of the central depot in Staten Island and

the district depot in Detroit. After the components were carefully

carried into the lantern, the lens was assembled atop the pedestal.

Designed to exhibit fixed white characteristic with a red flash every

sixty seconds, the lens was outfitted with an external ring outfitted

with prismatic ruby colored glass flash panels which rotated around the

outside the lens. Power for rotating the three ruby panels was provided

by a fan regulated clockwork mechanism connected to the ring by a series

of gears. A steel cable 22 feet in length was wound around a drum within

the clockworks, with the cable routed through the lantern floor to a

vertical shaft within the west wall of the tower, and a heavy weight

attached to the lower end of the cable. This weight slowly dropped down

within the shaft, it turned the drum, thereby rotating the panels

attached to the outer ring. By virtue of the station's location atop the

bluff, the lens sat at a focal plane of 60 feet above lake level, and

would be visible for a distance of 15 miles in clear weather. The district Lampist, Mr. Crump, arrived at the

station, and carefully uncrated the station's new Fourth

Order Fresnel lens which had been manufactured in France and

shipped to the station by way of the central depot in Staten Island and

the district depot in Detroit. After the components were carefully

carried into the lantern, the lens was assembled atop the pedestal.

Designed to exhibit fixed white characteristic with a red flash every

sixty seconds, the lens was outfitted with an external ring outfitted

with prismatic ruby colored glass flash panels which rotated around the

outside the lens. Power for rotating the three ruby panels was provided

by a fan regulated clockwork mechanism connected to the ring by a series

of gears. A steel cable 22 feet in length was wound around a drum within

the clockworks, with the cable routed through the lantern floor to a

vertical shaft within the west wall of the tower, and a heavy weight

attached to the lower end of the cable. This weight slowly dropped down

within the shaft, it turned the drum, thereby rotating the panels

attached to the outer ring. By virtue of the station's location atop the

bluff, the lens sat at a focal plane of 60 feet above lake level, and

would be visible for a distance of 15 miles in clear weather.

With construction of a wood barn, wood shed and brick

privy, and the laying of timber walkways connecting the structures, work

at the station was considered complete on September 28. Henry Stanley,

keeper of the Eagle Bluff light

station for the past 15 years was selected as the new station's

keeper, and while he appears on district payroll records as being

assigned to Sherwood Point on September 20, he did not officially

display the new light until the night of October 10, 1883.

Soon after taking over the station, Stanley began to

experience problems with the lens clockworks, having to pay for a

Sturgeons Bay clockmaker to make the trip to station in an attempt to

effect repairs. In 1884, Keeper Stanley's niece Minnie Hesh arrived at

the station from New York to spend some time with the Stanleys at the

station while recovering from the sudden death or her parent. Evidently

finding the area to her liking, Minnie decided to take up residence in

the area, and eventually married William Cochems, the son of a prominent

Sturgeons Bay businessman in 1889. Soon after taking over the station, Stanley began to

experience problems with the lens clockworks, having to pay for a

Sturgeons Bay clockmaker to make the trip to station in an attempt to

effect repairs. In 1884, Keeper Stanley's niece Minnie Hesh arrived at

the station from New York to spend some time with the Stanleys at the

station while recovering from the sudden death or her parent. Evidently

finding the area to her liking, Minnie decided to take up residence in

the area, and eventually married William Cochems, the son of a prominent

Sturgeons Bay businessman in 1889.

After seven years of supplying the station through the

time consuming process of lightering from anchored supply tenders to

Sawyers Harbor and thence along the rough half mile trail to the

lighthouse, District engineer Major William Ludlow requested a the sum

of $100 to purchase a small parcel of land adjacent to the station on

which he planned to erect a landing crib and stairs leading up the bluff

to the station. Concurring with the need, Congress appropriated the

requested sum on August 30, 1899, and steps were undertaken to obtain

title to the selected parcel. Stanley's problems with the lens became so

well known in the area, that on October 4, 1890 the Door County Advocate

took up Stanleys cause, commenting that he had "no end of

trouble since entering his duties down there to make the thing work at

all times, it being frequently necessary for him or an assistant to move

the machinery by hand." Clear title to the required land was

finally obtained on September 17, 1891, and a crew arrived at the

station that season to erect the necessary cribs and stairs for the

delivery of supplies.

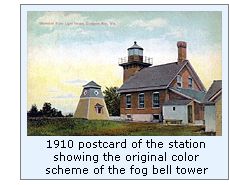

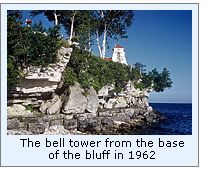

That winter, the decision was made to establish a fog

signal at the station to serve mariners making their way into the canal

entrance in thick and foggy weather. To this end, in the Spring of 1892,

a work crew was dispatched from Detroit to erect a square timber-framed

pyramidal structure to house the new fog bell at the upper edge of the

bluff in front of the lighthouse tower. Sheathed in horizontal siding,

the structure featured a shingled roof and four diamond-shaped windows

on the upper walls to allow light into the building's interior. A

600-pound bronze bell was attached to the lakeward wall of the structure

and an automated

bell striking mechanism within the structure and connected to a

hammer which was hinged to strike the bell on the outer wall through an

opening in the wall. Similar to the lens rotation mechanism, the bell

striker consisted of a clockwork motor, and required winding every four

hours when the bell was in operation ringing out its characteristic

single strike every 12 seconds. To make the new tower match the

appearance of the existing structures, the lower section of the tower

was painted a dark buff color and the upper section slate gray. Work on

the tower was completed, and the new fog bell placed officially into

operation on July 1, 1892. That winter, the decision was made to establish a fog

signal at the station to serve mariners making their way into the canal

entrance in thick and foggy weather. To this end, in the Spring of 1892,

a work crew was dispatched from Detroit to erect a square timber-framed

pyramidal structure to house the new fog bell at the upper edge of the

bluff in front of the lighthouse tower. Sheathed in horizontal siding,

the structure featured a shingled roof and four diamond-shaped windows

on the upper walls to allow light into the building's interior. A

600-pound bronze bell was attached to the lakeward wall of the structure

and an automated

bell striking mechanism within the structure and connected to a

hammer which was hinged to strike the bell on the outer wall through an

opening in the wall. Similar to the lens rotation mechanism, the bell

striker consisted of a clockwork motor, and required winding every four

hours when the bell was in operation ringing out its characteristic

single strike every 12 seconds. To make the new tower match the

appearance of the existing structures, the lower section of the tower

was painted a dark buff color and the upper section slate gray. Work on

the tower was completed, and the new fog bell placed officially into

operation on July 1, 1892.

By 1894, Stanley was 70 years old, and responsible for

both a difficult lighting apparatus and a fog signal, he managed to

convince Ninth District Inspector Commander John J. Brice that an

assistant was needed at the station to keep up with the increased

workload. Stanley likely pulled some strings to have his niece Minnie's

husband William appointed to the position, and Minnie and William

Cochems moved into the station with the Stanleys on November 10, 1894.

After suffering from illness for almost a year, Stanley passed away on

October 13, 1895. Surprisingly, a few weeks thereafter Cochems was

promoted to the position of Keeper of the Sherwood Point Light and

Katherine Stanley was appointed as his assistant. By 1894, Stanley was 70 years old, and responsible for

both a difficult lighting apparatus and a fog signal, he managed to

convince Ninth District Inspector Commander John J. Brice that an

assistant was needed at the station to keep up with the increased

workload. Stanley likely pulled some strings to have his niece Minnie's

husband William appointed to the position, and Minnie and William

Cochems moved into the station with the Stanleys on November 10, 1894.

After suffering from illness for almost a year, Stanley passed away on

October 13, 1895. Surprisingly, a few weeks thereafter Cochems was

promoted to the position of Keeper of the Sherwood Point Light and

Katherine Stanley was appointed as his assistant.

Evidently, Cochems continued to experience problems

with the operation of the lens rotating mechanism, as the Ninth District

Lampist arrived at the station on March 23, 1898, and replaced the

entire lens, pedestal and rotating mechanism with the illuminating

apparatus previously installed at the Passage

Island light, along with a new ball bearing rotating mechanism.

Deciding to retire from lighthouse service, Katherine Stanley resigned

her position on June 24 of this same year, and Minnie Cochems was

appointed to replace her on Katherine's departure, and William and

Minnie had the lighthouse to themselves and their children, and took

great pride in maintaining the lighthouse grounds in pristine condition.

Since the earliest days of the US lighthouse service,

lard and sperm oil ware used for fueling the lamps. Relatively

non-volatile, the oil was stored in special rooms in lighthouse cellars

or in the dwelling itself. With a change to the significantly more

volatile kerosene, a number of devastating dwelling fires were

experienced, and beginning late in the 1880's the Lighthouse Board began

building separate oil storage buildings at all US light stations. As a

result, it was surprising that the Sturgeon Point light was never

equipped with a separate oil storage building . This situation was

rectified in 1902 when a work crew and materials were delivered at the

station and a brick oil storage building was erected a safe distance

from the main building. Three years later, another crew arrived at the

station and replaced all of the timber walkways with concrete. The

district Lampist returned to the station on April 25, 1917 and upgraded

the lamp to an incandescent oil vapor system, thereby increasing the

output of the fixed white light to 1,700 candlepower and the red flash

to 4,300 candlepower.

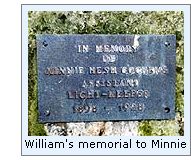

As Minnie was getting out of bed on August 17, 1928,

she collapsed and passed away. In tribute to his late wife, William

placed a plaque on a stone pedestal in the garden to the east of the

station which read "In memory of Minnie Hesh Cochems, Assistant

Light-Keeper, 1898 - 1928." With the arrival of electrical

power in the area, the station and light were electrified in 1930. After

Minnie's death, the position of assistant at the station was never

refilled, and this may have served as a contributing factor to William's

decision to retire from lighthouse service three years later on July 1,

1933 after almost 39 years of service at the station. As Minnie was getting out of bed on August 17, 1928,

she collapsed and passed away. In tribute to his late wife, William

placed a plaque on a stone pedestal in the garden to the east of the

station which read "In memory of Minnie Hesh Cochems, Assistant

Light-Keeper, 1898 - 1928." With the arrival of electrical

power in the area, the station and light were electrified in 1930. After

Minnie's death, the position of assistant at the station was never

refilled, and this may have served as a contributing factor to William's

decision to retire from lighthouse service three years later on July 1,

1933 after almost 39 years of service at the station.

Conrad Stram was transferred to Sherwood Point from

the Sturgeon Bay Canal

light where he had served for the past six years. With

establishment of the automated Peshtigo

Reef light on August 26, 1935, supervision, maintenance and

operation of the new light were added to Stram's responsibilities.

However, Stram would be required to operate both lights and the fog

signal single-handedly. With plans for the establishment of a

radiobeacon at the station for 1940, First and Second Assistant's were

assigned to the station in 1939. With the Coast Guard's assumption of

responsibility for the nation's aids to navigation in 1939, the civilian

keepers were given the alternative of either transferring into the Cost

Guard or maintaining their civilian status, which was the alternative

chosen by Stram.

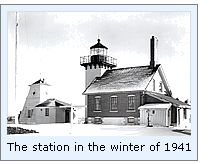

The fog signal was automated in 1940 through the

installation of electrically-operated diaphragm horns, and with the

automated bell ringing apparatus removed, the bell tower was converted

into a radio room. The following year, Stram changed his mind, and

transferred into the Coast Guard, and continued to serve as keeper of

the Sherwood Point Light until he retired in 1945. The fog signal was automated in 1940 through the

installation of electrically-operated diaphragm horns, and with the

automated bell ringing apparatus removed, the bell tower was converted

into a radio room. The following year, Stram changed his mind, and

transferred into the Coast Guard, and continued to serve as keeper of

the Sherwood Point Light until he retired in 1945.

Coast Guard crews continued to man the Sherwood Point

station through the fall of 1983, when the light was the last on the

Great Lakes to be automated. With the litharge which held the lens

prisms in place found to be significantly deteriorated as a result of

constant exposure to the sun's ultraviolet rays and a lack of daily

maintenance by full time keepers, the Fresnel lens was removed from the

lantern on October 21, 2002 and replaced by a 300

mm acrylic optic. The historic Fourth Order lens was transported

to the Door County Maritime Museum where it was restored by Coast Guard

Lampist Jim Woodward, and can currently be seen on display.

Keepers of

this Light

Click Here to see a complete listing of

all Sherwood Point Light keepers compiled by Phyllis L. Tag of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Finding this

light

This lighthouse is currently private Coast Guard property, and as such all access

is closed to the public. We obtained specific permission from the Coast

Guard to enter the grounds and take photographs for this website.

However, the station is open to the public every year during the annual Door County Lighthouse Walk

which is held in mid May every year.

Click

here to use the Museum's web-based brochure request form, or

contact the Museum at:

The Door County

Maritime Museum

120 N. Madison St.

Sturgeon Bay, WI 54235

(920) 743-5958

Reference Sources

Annual Reports of the Lighthouse

Board, Various, 1880 - 1909

Annual reports of the Commissioner of Lighthouses, 1910 - 1939

Engineers survey of the station, 1886

Annual reports of the Lake Carriers Association, 1906 - 1935

Door County Advocate, various, 1880 - 1920

Great Lakes Light Lists, various, 1886 - 1979Personal observation at Sherwood Point, 09/10/2000

Keeper listings for this light appear courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|