|

Historical

Information

Since the founding of the settlement of Michigan City, the

townsfolk had what at times seemed to be a losing battle with wind and

wave-born sand which clogged the entry to Trail Creek, stifling their

plans to make their city the important hub of maritime commerce of their

dreams.

The first steps towards federal harbor improvements at

the river mouth were undertaken in 1836, when $20,000 was appropriated

to begin the work. With additional appropriations increasing the

available funding to $110,000 by 1839, the Topographical Engineers

completed the erection of a pair or parallel timber crib piers on each

side of the river mouth. With the river thus opened up to greater

commerce, the citizenry of Michigan City was looking forward to boom

times, and in that first year alone, 150 barrels of whiskey, 50 barrels

of cider and vinegar, 50 barrels of apples, 7,887 bushels of salt, 1.344

bushels of bulk goods, and 1,105 tons of merchandise were shipped into

the harbor, and vessels departed loaded with wheat, corn, barley, oats,

rye, pork, lard, flour and butter.

While a government dredge had been assigned to the

harbor, it appeared as though it was of little advantage, as the depth

of water between the piers had decreased to the point that it was barely

sufficient to float a scow into the river by 1842. After an additional

appropriation of $10,000 in 1844, the piers were extended further into

the lake, and through frequent dredging a minimum navigable depth of

seven feet throughout the entrance was maintained. However, it was clear

that continued extension of the piers would afford insufficient

protection, and the Engineers recommended an appropriation of $177,000

for the erection of a 1,000-foot breakwater outside the pier entrance to

both retard sand deposition and serve as a harbor of refuge to mariners

during storms out on the lake. Reticent to appropriate the full sum,

Congress did approve an expenditure of $20,000 for harbor improvements

at Michigan City in 1852, and work on rebuilding and further extension

of the piers began the following year.

With the entrance between the new piers a considerable

distance from the Michigan City Lighthouse at the river mouth, the

Lighthouse Board decided that a pierhead beacon would be needed to mark

the entry, and an appropriation of $2,000 was made to this end on August

3, 1854. However, with the work still far from completion, installation

of the light was postponed until completion of pier construction, and

the appropriation was returned to the Treasury, and with the outset of

the Civil War in 1861, the Engineers were called to battle, and work on

the harbor came to a grinding halt. With the entrance between the new piers a considerable

distance from the Michigan City Lighthouse at the river mouth, the

Lighthouse Board decided that a pierhead beacon would be needed to mark

the entry, and an appropriation of $2,000 was made to this end on August

3, 1854. However, with the work still far from completion, installation

of the light was postponed until completion of pier construction, and

the appropriation was returned to the Treasury, and with the outset of

the Civil War in 1861, the Engineers were called to battle, and work on

the harbor came to a grinding halt.

Not content to sit back and allow the work on their

harbor to languish for an undetermined period of time, local business

interests formed the Michigan City Harbor Company, and with a stock

capitalization of $300,000 in stock, approached the federal government

to receive permission to build atop the existing piers in order to

continue the harbor improvements in accordance with Engineer's plan.

Congress not only gave approval to the endeavor, but appropriated an

additional $75,000 for the project, but insisted on making the

availability of the funds contingent on the Harbor Company's proving

that it had expended a minimum of $100,000 of its own operating capital

on the works.

While the Harbor Company was able to meet the demands

of the contingency in June of 1867, with the war over, the company was

reticent to continue expenditure of its own funds, and instead turned to

applying all possible pressure on the Federal Government to complete the

work. On behalf of the Company, the Indiana General Assembly passed a

resolution on February 1, 1869 that Congress be "respectfully

requested to make such an appropriation as may be necessary to complete

the harbor at Michigan City." Additionally, Michigan's Senators and

Representatives were requested "to vote and use their official

influence in favor of passage of said appropriation." Congress

responded favorably, assigning Major David C Houston to the task of

completing the work, and after conducting a situation assessment in May

1870, Houston concurred that the construction of an outer breakwater was

the only real solution, stating that "It seems impossible to

maintain the required depth of water at the harbor, except by constant

dredging ... and the only remedy seems to be the construction of an

outer harbor."

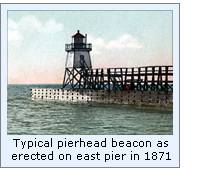

Thus, the

Army Corps of Engineers returned to Michigan

City in 1870, and with progress underway on extending both piers, the

Lighthouse Board again requested an appropriation for establishing a

beacon at the outer end of the longer pier on its completion. Funding

for the beacon was approved on March 3, 1871, and the structure was

erected that fall. Typical of pierhead beacons erected throughout the

district, the structure took the form of a 27-foot tall white-painted

timber framed pyramid beacon. With its upper section enclosed with

clapboard sheathing, a small enclosed room was thus formed within the

structure to serve double duty as both a service room and as shelter for

the keeper when forced to spend time tending the light in rough weather.

Atop this service room, an octagonal iron lantern was centered on a

square gallery, and outfitted with a fixed red Sixth Order Fresnel lens.

By virtue of the beacon's location atop the timber pier, the lens stood

at a focal plane of 32 feet, and was calculated to be visible for a

distance of 11 ½ miles in clear weather conditions. The indomitable

Harriet Colfax, who had been serving as keeper of the old Michigan City

Lighthouse since 1861, now found maintenance of the pierhead light added

to her responsibilities, and made her way along the wooden elevated

walkway and climbed the wooden ladder within the beacon to exhibit the

new light for the first time on the evening of November 20, 1871. Thus, the

Army Corps of Engineers returned to Michigan

City in 1870, and with progress underway on extending both piers, the

Lighthouse Board again requested an appropriation for establishing a

beacon at the outer end of the longer pier on its completion. Funding

for the beacon was approved on March 3, 1871, and the structure was

erected that fall. Typical of pierhead beacons erected throughout the

district, the structure took the form of a 27-foot tall white-painted

timber framed pyramid beacon. With its upper section enclosed with

clapboard sheathing, a small enclosed room was thus formed within the

structure to serve double duty as both a service room and as shelter for

the keeper when forced to spend time tending the light in rough weather.

Atop this service room, an octagonal iron lantern was centered on a

square gallery, and outfitted with a fixed red Sixth Order Fresnel lens.

By virtue of the beacon's location atop the timber pier, the lens stood

at a focal plane of 32 feet, and was calculated to be visible for a

distance of 11 ½ miles in clear weather conditions. The indomitable

Harriet Colfax, who had been serving as keeper of the old Michigan City

Lighthouse since 1861, now found maintenance of the pierhead light added

to her responsibilities, and made her way along the wooden elevated

walkway and climbed the wooden ladder within the beacon to exhibit the

new light for the first time on the evening of November 20, 1871.

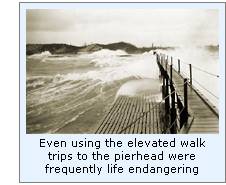

By virtue of its location at the eastern foot of the

lake, Michigan City was subject to numerous storms, and one can only

imagine the sight represented by this diminutive lady making her was out

to service the pierhead beacon in tempestuous weather. In typically

stoic terms a number of Miss Colfax's station log entries tell of her

difficulties, such as on September 18, 1872 when she reported "Cold

day. Heavy NW gale towards night. The waves dashing over both piers,

very nearly carrying me with them into the lake," and again on

September 29, when she wrote "Wind blowing a westerly gale all day

and still rising at 5 PM. Four vessels entered while the gale was at its

height & ran against the elevated walk, breaking it in again. Went

to the beacon tonight with considerable risk of life." By virtue of its location at the eastern foot of the

lake, Michigan City was subject to numerous storms, and one can only

imagine the sight represented by this diminutive lady making her was out

to service the pierhead beacon in tempestuous weather. In typically

stoic terms a number of Miss Colfax's station log entries tell of her

difficulties, such as on September 18, 1872 when she reported "Cold

day. Heavy NW gale towards night. The waves dashing over both piers,

very nearly carrying me with them into the lake," and again on

September 29, when she wrote "Wind blowing a westerly gale all day

and still rising at 5 PM. Four vessels entered while the gale was at its

height & ran against the elevated walk, breaking it in again. Went

to the beacon tonight with considerable risk of life."

By 1875, the west pier had been extended 800 feet

beyond the east pier to help shelter the opening from prevalent westerly

winds, and a lighthouse crew arrived and relocated the elevated walk

across the channel and re-erected it on the west pier along with 800

feet of new walk extending to shore. With completion of work on the

elevated walk, the beacon itself was loaded on a scow, and carried

across the channel and erected at the outer end of the pier and

connected to the elevated walk. This was no doubt a less than enjoyable

change for Harriet, as the main lighthouse was located across the

channel on the east shore, and thus she was forced to row her boat

across the channel to service the beacon every night. The following

year, the entire beacon was painted inside and out, and repairs made to

the elevated walk after it had been damaged by an unnamed vessel

entering the harbor the previous winter.

In 1882, work was well underway on erecting the 1,200

foot long timber crib east breakwater, and plans for the harbor were

further modified to include a 700-foot long detached breakwater to the

northwest of the pierhead entrance in a further attempt to stem sand

deposition. As a result of a major gale on the night if October 14,

1886, the pierhead beacon was ripped from the pier and destroyed by the

crashing waves. Deciding against reestablishment of the beacon, the

elevated walkway was removed from the west pier in 1891 and was shipped

by the Army Corps of Engineers to Ludington, where it was reassembled on

the south pier in that harbor. With frequent changes underway, the

Lighthouse Board and Army Corps of Engineers reached an agreement

whereby the Engineers would maintain a series of four tubular lanterns

on posts throughout the breakwater construction, thereby facilitation

frequent relocation of the lights as sections of breakwater were

completed. In 1882, work was well underway on erecting the 1,200

foot long timber crib east breakwater, and plans for the harbor were

further modified to include a 700-foot long detached breakwater to the

northwest of the pierhead entrance in a further attempt to stem sand

deposition. As a result of a major gale on the night if October 14,

1886, the pierhead beacon was ripped from the pier and destroyed by the

crashing waves. Deciding against reestablishment of the beacon, the

elevated walkway was removed from the west pier in 1891 and was shipped

by the Army Corps of Engineers to Ludington, where it was reassembled on

the south pier in that harbor. With frequent changes underway, the

Lighthouse Board and Army Corps of Engineers reached an agreement

whereby the Engineers would maintain a series of four tubular lanterns

on posts throughout the breakwater construction, thereby facilitation

frequent relocation of the lights as sections of breakwater were

completed.

With completion of the new outer east pierhead in

sight, the Lighthouse Board determined that the establishment of a

first-class fog signal at its outer end, and new beacons to mark the

ends of the west pierhead and breakwater would serve as valuable aids to

mariners, and thus a request for an appropriation of $5,500 was included

in the Board's annual report of 1894 for their erection. Without

Congressional action, the request was reiterated in each subsequent

annual report for the following five years. Congress finally responded

to the Board's repeated requests on June 6, 1900. when an act was

approved for establishing the new aids and immediately followed up with

the necessary appropriation. With the Engineers still working on the

outer end of the new breakwater, the work was postponed for two years

until the fall of 1903, when Ninth District Lighthouse Engineer Major

General Warren approved the detailed plans and specifications for the

new structures.

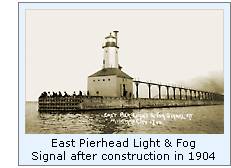

The required metal work for the three structures was

delivered to the lighthouse depot in Milwaukee over that winter, and

after loading in the lighthouse tender HYACINTH, was delivered to

Michigan City in June 1904, where a large work crew was waiting to help

unload the materials and begin construction. Over that summer, work in

the harbor reached a feverish pace as the construction crew worked on

erecting the three new structures and undertaking significant

modifications to the old dwelling.

The new East Pierhead fog signal and light tower

consisted of a 24' square structure built of 3/16" steel plates

standing 14' 10" tall at the eaves. Within this structure, a pair

of horizontal boilers manufactured by Kingsford Foundry in Oswego, New

York were installed and equipped with a cam activated Crosby automatic

timing apparatus to sequence the signals to attain the designated

characteristic. Developing an operating pressure of 100 psi, the boilers

were connected to a single 10" locomotive steam whistle located on

the lakeward side of the roof, and their exhaust gases evacuated through

a single 24" diameter stack which extended up through the roof to a

conical rain cap standing 45' 3" above the deck of the timber pier.

Centered atop the hipped roof, an octagonal tower of 3/16" thick

steel plate was erected containing a set of spiral cast iron stairs with

5 landings rising from the pier deck to the gallery. With an inscribed

diameter of 10' 6", the tower contained 4 portholes of 14 ¾"

diameter to allow light into the structure, and was capped with 7'

1" diameter circular iron lantern with diagonal astragals. A cast

iron pedestal was erected at the center of the lantern, and prepared to

receive the Fifth Order Fresnel lens from the old main light on

completion of the construction. The entire building and tower were given

a coat of buff-colored paint with the exception of the lantern, which

was painted black to help it serve as a more effective day mark. The new East Pierhead fog signal and light tower

consisted of a 24' square structure built of 3/16" steel plates

standing 14' 10" tall at the eaves. Within this structure, a pair

of horizontal boilers manufactured by Kingsford Foundry in Oswego, New

York were installed and equipped with a cam activated Crosby automatic

timing apparatus to sequence the signals to attain the designated

characteristic. Developing an operating pressure of 100 psi, the boilers

were connected to a single 10" locomotive steam whistle located on

the lakeward side of the roof, and their exhaust gases evacuated through

a single 24" diameter stack which extended up through the roof to a

conical rain cap standing 45' 3" above the deck of the timber pier.

Centered atop the hipped roof, an octagonal tower of 3/16" thick

steel plate was erected containing a set of spiral cast iron stairs with

5 landings rising from the pier deck to the gallery. With an inscribed

diameter of 10' 6", the tower contained 4 portholes of 14 ¾"

diameter to allow light into the structure, and was capped with 7'

1" diameter circular iron lantern with diagonal astragals. A cast

iron pedestal was erected at the center of the lantern, and prepared to

receive the Fifth Order Fresnel lens from the old main light on

completion of the construction. The entire building and tower were given

a coat of buff-colored paint with the exception of the lantern, which

was painted black to help it serve as a more effective day mark.

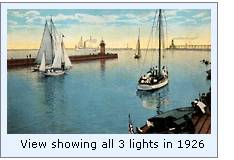

The new structure on the west pierhead took the form

of a buff painted cylindrical tower, which was a virtual duplicate of

the tower which had been erected at South Haven the previous year.

Standing 8' in diameter at the base, the structure tapered to a diameter

of 7' beneath the gallery, and was built of pre-formed steel plates

which progressively reduced in thickness from 5/16" at the base to

¼" below the gallery. Four 14 ¾ diameter porthole widows located

beneath the gallery allowed light to enter, guiding the way up the steel

stairs and ladder contained within. Atop the circular gallery, a black

painted decagonal iron lantern 7' in diameter housed a 5-day lens

lantern equipped with a ruby glass chimney to impart a red

characteristic to the light. Centered atop the lantern roof, a spherical

cast iron ventilator ball stood 27' 9" above the timber pier, and

was capped with a titanium-tipped lightning conductor. The new structure on the west pierhead took the form

of a buff painted cylindrical tower, which was a virtual duplicate of

the tower which had been erected at South Haven the previous year.

Standing 8' in diameter at the base, the structure tapered to a diameter

of 7' beneath the gallery, and was built of pre-formed steel plates

which progressively reduced in thickness from 5/16" at the base to

¼" below the gallery. Four 14 ¾ diameter porthole widows located

beneath the gallery allowed light to enter, guiding the way up the steel

stairs and ladder contained within. Atop the circular gallery, a black

painted decagonal iron lantern 7' in diameter housed a 5-day lens

lantern equipped with a ruby glass chimney to impart a red

characteristic to the light. Centered atop the lantern roof, a spherical

cast iron ventilator ball stood 27' 9" above the timber pier, and

was capped with a titanium-tipped lightning conductor.

To mark the end of the breakwater adjacent to the

harbor entry, a simple square concrete post was erected and topped by a

fixed red 5-day lens lantern.

While the old lighthouse building would no longer be

needed to serve as an aid to navigation, with three keepers planned to

manage the aids at the station, the old structure underwent a complete

modification to convert it into a triplex dwelling, with 4 rooms for the

head keeper and 3 rooms for each of his two assistants. As part of the

reconfiguration, porches were added on each side of the building and the

bricks of the upper floor were covered with dark green painted shingles.

A coal shed and double privy were erected to the rear of the station and

concrete walks poured to connect the station buildings. Thomas J. Armstrong, who had been serving as keeper of

the South Manitou Light Station for the past ten years accepted a

transfer as the station's new keeper, and Harriet Colfax officially

retired from lighthouse service on October 13, after 43 years as the

steward of the Michigan City light station. The Fifth Order lens was removed from the lantern and

reestablished atop the new East Pierhead light and fog signal, and all

three of the new lights officially exhibited for the first time on the

evening of October 20, 1904. No longer serving any purpose, the square

wooden tower and lantern atop the dwelling were removed, and the

building re-roofed. While the old lighthouse building would no longer be

needed to serve as an aid to navigation, with three keepers planned to

manage the aids at the station, the old structure underwent a complete

modification to convert it into a triplex dwelling, with 4 rooms for the

head keeper and 3 rooms for each of his two assistants. As part of the

reconfiguration, porches were added on each side of the building and the

bricks of the upper floor were covered with dark green painted shingles.

A coal shed and double privy were erected to the rear of the station and

concrete walks poured to connect the station buildings. Thomas J. Armstrong, who had been serving as keeper of

the South Manitou Light Station for the past ten years accepted a

transfer as the station's new keeper, and Harriet Colfax officially

retired from lighthouse service on October 13, after 43 years as the

steward of the Michigan City light station. The Fifth Order lens was removed from the lantern and

reestablished atop the new East Pierhead light and fog signal, and all

three of the new lights officially exhibited for the first time on the

evening of October 20, 1904. No longer serving any purpose, the square

wooden tower and lantern atop the dwelling were removed, and the

building re-roofed.

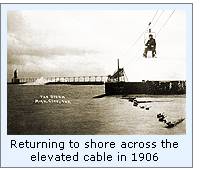

During a particularly devastating storm in the late

winter of 1905 - 1906, a large section of the outer east pier was

completely obliterated, leaving a gaping hole in structure, the west

pierhead light was inundated and pushed off its foundation and into the

harbor, forcing the keepers to make their was out to the fog signal by

way of the station boat. On the opening of the 1906 navigation season, a

lighthouse crew arrived at the station and erected a temporary post at

the end of the west pier from which a lens lantern was installed until

the cylindrical beacon could be retrieved and re-erected later that

year, and until the Army Corps of Engineers could effect a permanent

repair to the devastated east pier, a temporary 400-foot long wire cable

lifeline was installed to bridge the gap, and the keepers were forced to

take a "joy ride" across the gap, seated on a metal seat

suspended from the cable by pulleys. While this was likely considered a

less than enjoyable experience by the keepers, it was almost certainly

safer than attempting to scramble up the face of the east breakwater in

heavy seas from their bucking boat. Work on rebuilding the pier was

completed in 1907, and 1,000 feet of cast iron elevated walk were

erected to replace that which had been destroyed by the storm. 1907 was

also likely a memorable year for the keepers at Michigan City, as they

toiled to feed 29 tons of coal and 2 cords of wood into the hungry fog

signal boilers in order to keep their signal screaming its warning

across the lake a station record 275 hours. During a particularly devastating storm in the late

winter of 1905 - 1906, a large section of the outer east pier was

completely obliterated, leaving a gaping hole in structure, the west

pierhead light was inundated and pushed off its foundation and into the

harbor, forcing the keepers to make their was out to the fog signal by

way of the station boat. On the opening of the 1906 navigation season, a

lighthouse crew arrived at the station and erected a temporary post at

the end of the west pier from which a lens lantern was installed until

the cylindrical beacon could be retrieved and re-erected later that

year, and until the Army Corps of Engineers could effect a permanent

repair to the devastated east pier, a temporary 400-foot long wire cable

lifeline was installed to bridge the gap, and the keepers were forced to

take a "joy ride" across the gap, seated on a metal seat

suspended from the cable by pulleys. While this was likely considered a

less than enjoyable experience by the keepers, it was almost certainly

safer than attempting to scramble up the face of the east breakwater in

heavy seas from their bucking boat. Work on rebuilding the pier was

completed in 1907, and 1,000 feet of cast iron elevated walk were

erected to replace that which had been destroyed by the storm. 1907 was

also likely a memorable year for the keepers at Michigan City, as they

toiled to feed 29 tons of coal and 2 cords of wood into the hungry fog

signal boilers in order to keep their signal screaming its warning

across the lake a station record 275 hours.

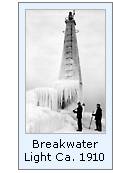

In yet another violent storm in 1909, the breakwater

light was destroyed, and the breakwater thus remaining unmarked until

1911, when a new pyramidal concrete structure was erected in is place.

The foundation of the new light consisted of a tank house standing 5'

7" by 7' 9" in plan, above which a four-sided concrete

structure stood 5' square at the base and tapered to 2' 6" square

at its upper level 16 feet above the foundation. Atop the tower at a

32-foot focal plane, a 50-candlepower 200 mm American Gas Accumulator

buoy lantern and sun valve was installed, visible for a distance of 16

miles in clear weather. In yet another violent storm in 1909, the breakwater

light was destroyed, and the breakwater thus remaining unmarked until

1911, when a new pyramidal concrete structure was erected in is place.

The foundation of the new light consisted of a tank house standing 5'

7" by 7' 9" in plan, above which a four-sided concrete

structure stood 5' square at the base and tapered to 2' 6" square

at its upper level 16 feet above the foundation. Atop the tower at a

32-foot focal plane, a 50-candlepower 200 mm American Gas Accumulator

buoy lantern and sun valve was installed, visible for a distance of 16

miles in clear weather.

In 1917, the color schemes of both the east and west

pierhead lights were changed, with the east pierhead fog signal being

painted white with a red roof and the west pierhead beacon painted red

with a black lantern. Also on May 17 of this year, the west pierhead

beacon was converted to acetylene power, with its characteristic changed

to a red flash of one second duration followed by an eclipse of 5

seconds.

Municipal electricity was run out along the east pier

in 1933, allowing the automation of the fog signal through the

installation of a Cunningham air whistle and the replacement of the oil

vapor lamp in the Fifth Order Fresnel with a 5,000 candlepower

incandescent electric light bulb. Municipal electricity was run out along the east pier

in 1933, allowing the automation of the fog signal through the

installation of a Cunningham air whistle and the replacement of the oil

vapor lamp in the Fifth Order Fresnel with a 5,000 candlepower

incandescent electric light bulb.

Strapped for funds and the necessary manpower to

maintain the obsolete iron elevated walkway in the east pier, the Coast

Guard began considering removal of the structure in the mid 1980's.

Learning of the possibility that the historic walkway might be removed,

concerned Michigan City citizens were successful in having the walkway

listed on National Register of Historic places in 1988. Stuck between a

rock and a hard place, the Coast Guard offered to donate the walkway to

the City in 1991, and in 1994 the city launched a fund raising campaign

to raise the necessary funds for restoration of the structure.

Keepers of

this Light

Click here

to see a complete listing of all the keepers of the Michigan East

Breakwater Light compiled by Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Finding this Light

Take 421 North into Michigan City, through downtown and to the

Lakeshore. As 421 intersects with Lakeshore Drive, continue North into

the park. The old shore lighthouse museum is to the left, and the pier

light is to the east and approximately 1/4 mile further north around the

Marina.

Reference Sources

Annual reports if the

Fifth Auditor of the Treasury, various, 1839 - 1852

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Board, various, 1853 – 1909

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Service, various, 1910 – 1929

Great Lakes Light Lists, various, 1849 – 1958

Journals of the US Congress, various, 1834 – 1876

Annual reports of the Lake Carriers Association, various, 1911

– 1944

Those Army Engineers, John W Larson, 1979

Women Who Kept The Lights, Mary Louise and J Candace Clifford,

1993

Keeper listings for this light appear courtesy of Great Lakes Lighthouse

Research

|