|

Historical

Information

For centuries the area around Little Traverse Bay had been the home of

Ottawa Indians. Around 1700, French Jesuits arrived in the area and

constructed a mission at the famous L'Arbre Croche village, a huge

native village which stretched from Cross Village to Harbor Springs.

Dependant on agriculture, fishing and trapping in 1847, the village of

L'Arbre Croche was home to the largest concentration of natives people

in what would become the state of Michigan.

With the Richard Cooper's establishment of his store in 1853, a few

white settlers began to move into the area, however in accordance with

treaty agreements made in Detroit in 1855, the native people continued

to hold most of the prime land around the bay. With beginning

exploitation of the rich forest resources surrounding the bay, the

Michigan Legislature passed a resolution requesting federal funding of

harbor improvements in Little Traverse Bay, and the erection of a

lighthouse to guide vessels around the point which protruded into the

northern arm of the bay. With the Richard Cooper's establishment of his store in 1853, a few

white settlers began to move into the area, however in accordance with

treaty agreements made in Detroit in 1855, the native people continued

to hold most of the prime land around the bay. With beginning

exploitation of the rich forest resources surrounding the bay, the

Michigan Legislature passed a resolution requesting federal funding of

harbor improvements in Little Traverse Bay, and the erection of a

lighthouse to guide vessels around the point which protruded into the

northern arm of the bay.

After simultaneous memorials were presented in the Senate and House

on March 13, 1871, the matter was referred to the Commerce Committee for

evaluation, with the Commerce Committee in turn forwarding the request

to Brevet Brigadier General Orlando M.

Poe, the Chief Engineer of the

Ninth District for his evaluation. In his report to the Commerce

Committee dated April 11, Poe observed that "By reference to the

tracing of the lake-survey detail chart of Little Traverse, enclosed

herewith Ö the relation of the harbor of Little Traverse to the

navigation of Lake Michigan can be readily seen and appreciated. The

harbor itself is excellent in every respect, easy of access, affording

good anchorage and a complete shelter from all winds. A Light-house of

the fifth-order, together with a Fog-bell of 600 pounds with Stevenís

striking apparatus, will make the harbor available. In addition to its

relation to the general commerce of Lake Michigan, the harbor has some

local importance. This is increasing, and, doubtless, will continue to

do so." Following-up on Poeís report, the Lighthouse Board

requested an appropriation for $15,000 in its annual report for 1873.

However, strapped for funds, Congress ignored the request. While the

Board reiterated its request for funding the following year, the matter

was soon dropped in favor of more important projects elsewhere

throughout the system.

As was frequently the case, treaties with the native Americans were

frequently and expeditiously "modified" after their original

signing, and with the passage of treaty limitations in 1875, the land

around Little Traverse Bay was opened-up for settlers, and the flood

gates opened. Harbor Springs was formally incorporated as a village in

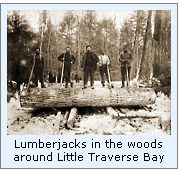

1880. After the opening of land availability, land lookers moved through the

area, claiming huge tracts of forest for their respective companies,

with lumbering operations following quickly on their heels.

Simultaneously with this commercial boom, word of the beauty of the bay,

its sunsets, clean air, cool breezes and clear water spread throughout

the Midwest, and an ever increasing number of moneyed individuals, their

pockets bulging with the bounty of the industrialization of the southern

Michigan cities began pouring into the area, building summer cottages,

mansions and hotels.

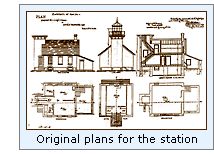

With this unprecedented boom in commercial and recreational activity,

there was a massive increase in vessel traffic in Little Traverse Bay,

and local interests again began petitioning for the construction of the

lighthouse recommended almost ten years previously. This time, the

response was more positive, with Congress approving the $15,000

appropriation for the establishment of a light at Little Traverse on

August 7, 1882. By the end of the year, plans for the new station had

been drawn up, and a survey team dispatched to identify the ideal

location for the new station. With this unprecedented boom in commercial and recreational activity,

there was a massive increase in vessel traffic in Little Traverse Bay,

and local interests again began petitioning for the construction of the

lighthouse recommended almost ten years previously. This time, the

response was more positive, with Congress approving the $15,000

appropriation for the establishment of a light at Little Traverse on

August 7, 1882. By the end of the year, plans for the new station had

been drawn up, and a survey team dispatched to identify the ideal

location for the new station.

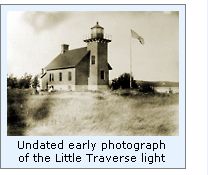

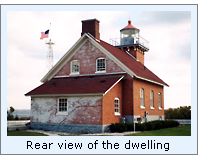

After obtaining clear title to the selected reservation early in

1884, a construction crew was delivered to Harbor Point on May 14, and

work at the site began in earnest. By June 30, the basement had been

excavated and the cut stone foundation walls laid. Joists for the first

floor had been installed and the brickwork carried up to a height of two

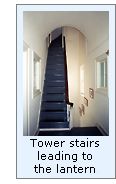

feet above the foundation level. The 1 ½-story brick dwelling stood 25í

by 37 feet in plan, with a 10í square tower standing 30 feet in height

integrated into its south gable end. The tower was capped by a square

copper-floored gallery with iron hand railings, centered on which an

octagonal cast iron lantern was installed. The District Lampist arrived

from Detroit and installed the stationís fixed red Fourth Order

Fresnel lens ordered from Sautter and Lemonier of Paris, France. 42-year

old Elizabeth Whitney Williams accepted a transfer from the St. James

Harbor lighthouse on Beaver Island where she had been serving for the

past twelve years. Construction was completed on September 18, and with

Elizabethís and her husband Danielís arrival, she climbed the stairs

of her new station and officially exhibited the new light on the evening

of September 25, 1884, sending the light 13 miles across the bay. After obtaining clear title to the selected reservation early in

1884, a construction crew was delivered to Harbor Point on May 14, and

work at the site began in earnest. By June 30, the basement had been

excavated and the cut stone foundation walls laid. Joists for the first

floor had been installed and the brickwork carried up to a height of two

feet above the foundation level. The 1 ½-story brick dwelling stood 25í

by 37 feet in plan, with a 10í square tower standing 30 feet in height

integrated into its south gable end. The tower was capped by a square

copper-floored gallery with iron hand railings, centered on which an

octagonal cast iron lantern was installed. The District Lampist arrived

from Detroit and installed the stationís fixed red Fourth Order

Fresnel lens ordered from Sautter and Lemonier of Paris, France. 42-year

old Elizabeth Whitney Williams accepted a transfer from the St. James

Harbor lighthouse on Beaver Island where she had been serving for the

past twelve years. Construction was completed on September 18, and with

Elizabethís and her husband Danielís arrival, she climbed the stairs

of her new station and officially exhibited the new light on the evening

of September 25, 1884, sending the light 13 miles across the bay.

With the creation of the Twelfth Lighthouse District, which

encompassed all of Lake Michigan on July 25, 1886, a search was on for a

location for a buoy depot to serve the northern portion of the lake.

Identifying that the protection offered by Harbor Point represented a

perfect location for such an facility, the Board requested an

appropriation of $50.000 to purchase a site and erect the necessary

sheds and wharves at Little Traverse. However, this request was not

repeated in subsequent reports, and the buoy depot was eventually

established at Charlevoix. With the creation of the Twelfth Lighthouse District, which

encompassed all of Lake Michigan on July 25, 1886, a search was on for a

location for a buoy depot to serve the northern portion of the lake.

Identifying that the protection offered by Harbor Point represented a

perfect location for such an facility, the Board requested an

appropriation of $50.000 to purchase a site and erect the necessary

sheds and wharves at Little Traverse. However, this request was not

repeated in subsequent reports, and the buoy depot was eventually

established at Charlevoix.

With increasing population, a municipal water supply was established

at Harbor Sprigs 1891, and the Twelfth District Engineer Major William

Ludlow took advantage of the availability of the supply of clean potable

water by having the station hooked-up to the system that same year.

Three years later, a summer kitchen was erected, a new woodshed was

constructed, the old woodshed converted into a barn for Mrs. Williamís

horse, and wooden sidewalks laid to connect all of the station

buildings. With increasing population, a municipal water supply was established

at Harbor Sprigs 1891, and the Twelfth District Engineer Major William

Ludlow took advantage of the availability of the supply of clean potable

water by having the station hooked-up to the system that same year.

Three years later, a summer kitchen was erected, a new woodshed was

constructed, the old woodshed converted into a barn for Mrs. Williamís

horse, and wooden sidewalks laid to connect all of the station

buildings.

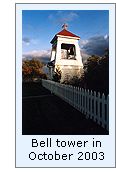

To serve the growing number of pleasure boats transporting

vacationers in and out of the harbor in thick weather, a fog bell tower

was established on the point in front of the lighthouse on June 1, 1896.

Standing 18-feet tall at the eaves, the tower was divided into upper and

lower sections. The bell was suspended in the open upper section and a

Stevens automated bell striking apparatus located in the enclosed lower

section. Powered by a weight within a vertical wooden conduit, with its

cable wound around a drum on the mechanism, the weight was cranked to

the top of the conduit, and the drum rotated as the weight slowly fell

to the bottom of the conduit. The mechanisms within the Stevens

apparatus converted this rotary motion to a linear motion, which was

then transferred to a large hammer which struck the bell with two sharp

blows every 30 seconds.

I

n the early days of the US lighthouse service, lard and sperm oil

ware used for fueling the lamps. Relatively non-volatile, the oil was

stored in special rooms in lighthouse cellars or in the dwelling itself.

With a change to the significantly more volatile kerosene, a number of

devastating dwelling fires were experienced, and beginning late in the

1880's the Lighthouse Board began building separate oil storage

buildings at all US light stations. To this end, a work crew and

materials were delivered at the station in 1898, and a brick oil storage

building was erected a safe distance from the main building. n the early days of the US lighthouse service, lard and sperm oil

ware used for fueling the lamps. Relatively non-volatile, the oil was

stored in special rooms in lighthouse cellars or in the dwelling itself.

With a change to the significantly more volatile kerosene, a number of

devastating dwelling fires were experienced, and beginning late in the

1880's the Lighthouse Board began building separate oil storage

buildings at all US light stations. To this end, a work crew and

materials were delivered at the station in 1898, and a brick oil storage

building was erected a safe distance from the main building.

Other than the installation of a lightning rod on the tower the

following year, Elizabethís life at Little Traverse settled into a

peaceful routine for the next decade. While her husband Daniel

photographed the resort country around the bat, selling his images the

summer resort visitors, the relative peace and quiet afforded Elizabeth

the opportunity to write her recollections of childhood on Beaver Island

during the reign of King James Strang, and her life as keeper of the Stí

James Harbor lighthouse after the death of her first husband. At the

urging of friends, the 63-year old Elizabeth published her famous

autobiography "A Child of the Seaí in 1905, with Elizabethís

memoirs bringing considerable admiration, as people learned of her

interesting and trying life story. After 43 years of lighthouse service,

Elizabeth retired in 1913, and she and Daniel retired in Charlevoix,

where she had spent her winters during her years tending the Beaver

Harbor light. Other than the installation of a lightning rod on the tower the

following year, Elizabethís life at Little Traverse settled into a

peaceful routine for the next decade. While her husband Daniel

photographed the resort country around the bat, selling his images the

summer resort visitors, the relative peace and quiet afforded Elizabeth

the opportunity to write her recollections of childhood on Beaver Island

during the reign of King James Strang, and her life as keeper of the Stí

James Harbor lighthouse after the death of her first husband. At the

urging of friends, the 63-year old Elizabeth published her famous

autobiography "A Child of the Seaí in 1905, with Elizabethís

memoirs bringing considerable admiration, as people learned of her

interesting and trying life story. After 43 years of lighthouse service,

Elizabeth retired in 1913, and she and Daniel retired in Charlevoix,

where she had spent her winters during her years tending the Beaver

Harbor light.

On November 3, 1913, Alfred Erickson accepted a transfer from the

Calumet Pierhead Light where he had been serving as Keeper for the past

two years. A young man of twenty-six, Ericson had entered lighthouse

service at the age of seventeen, with his first assignment being as

Second Assistant at Plum

Island, before serving at Chicago Harbor and

Sheboygan Pierhead stations before accepting his transfer to Calumet in

1911.

Other than a change in the characteristic of the fog bell from a

double stroke every 30 seconds to a single stroke every 30 seconds in

1914, Ericsonís life settled into the same quite routine as Elizabethís

before him, and he continued to enjoy duty at Little Traverse until he

resigned from service in 1940, the year after President Roosevelt

transferred responsibility for the nationís aids to navigation to the

Coast Guard in 1939. With this transfer, the old "Wickies"

were given the option of continuing as civilians, or transferring into

the Coast Guard. Many of the old civilian keepers could not stand the

mountains of paperwork resulting from the Coast Guard takeover, and

since Ericson was only 53 years of age, it is likely that he found other

work in the area. With the Coast Guard takeover, the characteristic of

the light was changed from fixed red to fixed green. Other than a change in the characteristic of the fog bell from a

double stroke every 30 seconds to a single stroke every 30 seconds in

1914, Ericsonís life settled into the same quite routine as Elizabethís

before him, and he continued to enjoy duty at Little Traverse until he

resigned from service in 1940, the year after President Roosevelt

transferred responsibility for the nationís aids to navigation to the

Coast Guard in 1939. With this transfer, the old "Wickies"

were given the option of continuing as civilians, or transferring into

the Coast Guard. Many of the old civilian keepers could not stand the

mountains of paperwork resulting from the Coast Guard takeover, and

since Ericson was only 53 years of age, it is likely that he found other

work in the area. With the Coast Guard takeover, the characteristic of

the light was changed from fixed red to fixed green.

With improvements in RADAR and LORAN-C in the late 1950ís, the

vital role played by the old lighthouses and fog signals faded, and a

move was on to automate as many lights as possible in order to eliminate

the costs associated with full time crews at the stations. To this end,

a work crew arrived at Harbor Point in 1963 and erected a 41-foot tall

white-painted steel skeleton tower, outfitted with a flashing green

electric light. Standing at a focal plane of 72 feet, the new light was

visible for a distance of 14 miles. With improvements in RADAR and LORAN-C in the late 1950ís, the

vital role played by the old lighthouses and fog signals faded, and a

move was on to automate as many lights as possible in order to eliminate

the costs associated with full time crews at the stations. To this end,

a work crew arrived at Harbor Point in 1963 and erected a 41-foot tall

white-painted steel skeleton tower, outfitted with a flashing green

electric light. Standing at a focal plane of 72 feet, the new light was

visible for a distance of 14 miles.

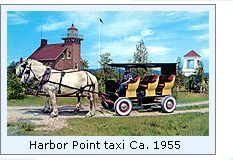

The old lighthouse property was sold to the exclusive and gated

Harbor Springs community in which it was isolated, and remains under the

collective ownership of the community to this day. The grounds are

maintained in immaculate condition, and while no longer illuminated, the

Fourth Order Fresnel lens can still be seen sitting proudly within the

stationís lantern

Keepers of this Light

Click Here

to see a complete listing of

all Little Traverse Light keepers compiled by Phyllis L. Tag of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Finding this Light

Take US-31 to downtown Petoskey, and turn off at the entrance to the

municipal marina, where there are plenty of parking spaces. If you do

not have your own boat, the only way to obtain offshore views of the

station will be by hiring a charter fishing boat to take you out to the

Point.

Note that it is impossible to gain access to the

station from the land, as there is only one road leading out to the

Point, and it passes right through the guarded entrance to the gated

community of Harbor Point.

Reference Sources

Journals of the US Senate

and House of Representatives, March 13, 1871

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Board, various, 1871 - 1909

Annual report of the Lake Carrier's Association, 1914

Little Traverse Lighthouse, pamphlet, Harbor Point Association

A look around Little Traverse Bay, Mary Candace Eaton, Little

Traverse Historical Society.

The Northern Lights, Charles K. Hyde, Ann & John Mahan, 1996

Personal observations at Harbor Point, 09/16/2000 |