|

Historical

Information

It is hard to imagine digging into the

history of the Beaver Island Harbor Lighthouse without coming across the

name of Elizabeth Whitney Williams. Little did the four-year-old child,

who arrived on the island with her family in 1846, know that she would

become so much a part of Beaver Island history. For Elizabeth would

eventually carve herself a position of immortality some fifty-nine years

later with the publication of her autobiography "A child of the sea

- Life among the Mormons."

Two years after the Whitney family took

up residence in the Irish fishing community, James Jesse Strang and his

group of Mormon followers arrived, inexorably changing the complexion of

life on the bucolic island. As a carpenter, Elizabeth's father Walter

was employed at various times by Strang. While not of the Mormon faith,

Walter somehow earned Strang's trust, as it was Walter that Strang chose

to build his new residence on the his new island kingdom.

As Strang's control of the island

widened, life became increasingly uncomfortable for the island's

"gentiles," as those of non-Mormon faith came to be known.

Fearing for the lives of his wife and daughter, Walter moved his wife

and daughter off the island to Charlevoix in1852. Whitney's two sons

stayed behind, having invested too much in their fishing business to

abandon. As Strang's control of the island

widened, life became increasingly uncomfortable for the island's

"gentiles," as those of non-Mormon faith came to be known.

Fearing for the lives of his wife and daughter, Walter moved his wife

and daughter off the island to Charlevoix in1852. Whitney's two sons

stayed behind, having invested too much in their fishing business to

abandon.

Strang's hold on the community ended

abruptly in 1856, when mortally wounded by a band of followers, he left

the island to die some weeks later in Wisconsin. Without the strength of

their leader, most of the remaining Mormons were easily driven from the

island by the remaining fishermen with help from a band from Mackinac

Island who were committed to ridding the area of the "Strangite

influence" once and for all.

1856 was also the year in which the

Lighthouse Board constructed the first lighthouse on Whiskey Point. The

need for a light on Beaver Island had long been realized, having been

mentioned as early as 1838 by Lieutenant James T Homans in his report on

Great Lakes lights to Stephen Pleasonton, the Fifth Auditor of the

Treasury. In that report, Homans indicated that "The loss of

property from shipwrecks on the Beaver Island has been considerable this

season alone, and in value to exceed the cost of building many

light-houses and maintaining them." However, under The Fifth

Auditors tight-fisted financial control of the department, no action was

taken on Homan's recommendation. With the appointment of the Lighthouse

Board in 1852, the nation's aids to navigation were looked upon in a new

light, with consideration of maritime interests taking a higher priority

than least-cost operation. 1856 was also the year in which the

Lighthouse Board constructed the first lighthouse on Whiskey Point. The

need for a light on Beaver Island had long been realized, having been

mentioned as early as 1838 by Lieutenant James T Homans in his report on

Great Lakes lights to Stephen Pleasonton, the Fifth Auditor of the

Treasury. In that report, Homans indicated that "The loss of

property from shipwrecks on the Beaver Island has been considerable this

season alone, and in value to exceed the cost of building many

light-houses and maintaining them." However, under The Fifth

Auditors tight-fisted financial control of the department, no action was

taken on Homan's recommendation. With the appointment of the Lighthouse

Board in 1852, the nation's aids to navigation were looked upon in a new

light, with consideration of maritime interests taking a higher priority

than least-cost operation.

We have been as yet unable to find

definite information as to the appearance of this first structure.

However it would appear that it was both small and ill-constructed, and

as a result was not likely considered to be a particularly enjoyable

assignment by Lyman Granger, the station's first keeper.

With Strang's departure, life on the

island finally returned to a sense of normalcy, and many of the exiled

settlers began returning to the island the following year. Among them

the Whitney's who took up residence in the abandoned "Strang

house," which Walter had helped build a few years previous. With Strang's departure, life on the

island finally returned to a sense of normalcy, and many of the exiled

settlers began returning to the island the following year. Among them

the Whitney's who took up residence in the abandoned "Strang

house," which Walter had helped build a few years previous.

Lyman Granger left the Service on

December 7, 1859, and Peter McKindley took over as the station's second keeper.

In 1860, at the age of 18, Elizabeth

married Clement Van Riper, and the newlyweds took up residence in a

house on Whiskey Point near the lighthouse, where Elizabeth established

a close relationship with McKindley's daughters. Clement established a

successful cooper shop on the Point, which he operated during the summer

months, he and Elizabeth preferring to spend the winters off the island

in various locations around Lake Michigan.

With the increase in lumber shipments

making the Manitou Passage bound from the ports of Western Michigan, the

Lighthouse Board recommended in its 1867 annual report that a new and

larger light be constructed on Whiskey Point to better guide traffic

into the harbor, thereby increasing its effectiveness as both a port and

a harbor of refuge. With considerable pressure applied by Michigan's

Lumber Barons, Congress responded favorably the following July with an

appropriation of $5,000 for construction of the station. With the increase in lumber shipments

making the Manitou Passage bound from the ports of Western Michigan, the

Lighthouse Board recommended in its 1867 annual report that a new and

larger light be constructed on Whiskey Point to better guide traffic

into the harbor, thereby increasing its effectiveness as both a port and

a harbor of refuge. With considerable pressure applied by Michigan's

Lumber Barons, Congress responded favorably the following July with an

appropriation of $5,000 for construction of the station.

Unfortunately for Keeper McKinley, was

unable to enjoy the planned station as failing health forced him to

resign his position in August 1869. Clement applied for, and was

appointed to the keeper's position. Closing his cooperage, he and

Elizabeth took over the full-time duties at the lighthouse. Elizabeth

evidently took to the lighthouse life, as she was soon involved in

cleaning and tending the station's illuminating apparatus..

In

the spring of 1870 a lighthouse tender arrived at the island and

unloaded a work party along with the necessary supplies for the

construction of the new light station. Built of Cream City

brick, the

story and a half keepers dwelling with matching summer kitchen was

attached to a forty-one feet tall cylindrical tower capped with a

decagonal prefabricated iron lantern, housing a new red Fourth Order

Fresnel lens manufactured by Barbier Fenestre of Paris. In

the spring of 1870 a lighthouse tender arrived at the island and

unloaded a work party along with the necessary supplies for the

construction of the new light station. Built of Cream City

brick, the

story and a half keepers dwelling with matching summer kitchen was

attached to a forty-one feet tall cylindrical tower capped with a

decagonal prefabricated iron lantern, housing a new red Fourth Order

Fresnel lens manufactured by Barbier Fenestre of Paris.

Soon after taking his appointment,

Clement also took ill, and Elizabeth took over all keepers duties while

her husband recovered. Elizabeth took great pride in maintaining the new

light station, paying special attention to labors involved in keeping

the lard oil fired lamp burning brightly under the harshest conditions.

One

dark and stormy night in 1872, Elizabeth and Clement became aware of a

loud flapping of sails in the distance and could barely make out the

flashing lights of a vessel n distress through the inky darkness. As

they strained their eyes to make out her shape rounding the point into

the harbor, the vessel sink before their eyes. While still in ill health

Clement and the first mate of the schooner Thomas Howland put out to see

if they could help any survivors. As Elizabeth watched her husband row

out into the darkness, she could not know it would be the last time she

would see him. No trace of either Clement of his companion were ever

found. One

dark and stormy night in 1872, Elizabeth and Clement became aware of a

loud flapping of sails in the distance and could barely make out the

flashing lights of a vessel n distress through the inky darkness. As

they strained their eyes to make out her shape rounding the point into

the harbor, the vessel sink before their eyes. While still in ill health

Clement and the first mate of the schooner Thomas Howland put out to see

if they could help any survivors. As Elizabeth watched her husband row

out into the darkness, she could not know it would be the last time she

would see him. No trace of either Clement of his companion were ever

found.

While Elizabeth was heartbroken, she

would later write that "though the life that was dearest to me had

gone, yet there were others out in the dark and treacherous waters who

needed the rays from the shining light of my tower. Nothing could rouse

me but that thought, then all my life and energy was given to the work

which now seemed was given me to do. While Elizabeth was heartbroken, she

would later write that "though the life that was dearest to me had

gone, yet there were others out in the dark and treacherous waters who

needed the rays from the shining light of my tower. Nothing could rouse

me but that thought, then all my life and energy was given to the work

which now seemed was given me to do.

Elizabeth's

stewardship of the light was quickly noticed by the authorities, and she

was appointed as keeper of the Beaver Island Harbor Light a short time

thereafter. Three years after Clement's tragic death, Elizabeth married

Daniel Williams, who moved into Elizabeth's lighthouse, while she

continued to faithfully tend the light for the following nine years.

In 1884, at the age of 42, Elizabeth

requested that she be transferred to a mainland light. Responding to her

request, she was transferred to the Little Traverse lighthouse in Harbor

Springs.

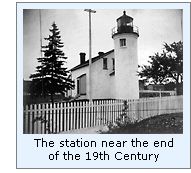

The following year, the steam barge

Ruby again delivered a work party at the Beaver Island Harbor Light to

undertake major repairs to the fifteen year old station. To stabilize

the structure, the cellar beneath the dwelling was filled-in, the former

barn was converted into a summer kitchen, and a 10 foot by 12 foot oil

storage building was built for the storage of the volatile kerosene

which was now being used as the primary illuminant throughout the

system. The following year, the steam barge

Ruby again delivered a work party at the Beaver Island Harbor Light to

undertake major repairs to the fifteen year old station. To stabilize

the structure, the cellar beneath the dwelling was filled-in, the former

barn was converted into a summer kitchen, and a 10 foot by 12 foot oil

storage building was built for the storage of the volatile kerosene

which was now being used as the primary illuminant throughout the

system.

Elizabeth continued on as head keeper

of the Little Traverse

Lighthouse, writing her memoirs while her husband

photographed the resort country around the bay, selling his images to

the summer resort visitors. Elizabeth's memoirs titled "A Child of

the Sea" were published in 1905, and brought her considerable

admiration as people learned of her interesting and difficult story.

Elizabeth continued to serve at Little

Traverse until 1913, when she retired at the age of 71, after forty-one

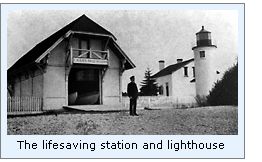

years of dedicated public service. The Beaver Island Harbor Lighthouse

was automated in 1927, and maintained by coast guardsmen working out of

the old lifesaving station around the bay. With the keeper's dwelling no

longer required, the structure along with all outbuildings were

demolished in the 1940's, leaving the forty-one foot tower standing

alone on Whiskey Point. Elizabeth continued to serve at Little

Traverse until 1913, when she retired at the age of 71, after forty-one

years of dedicated public service. The Beaver Island Harbor Lighthouse

was automated in 1927, and maintained by coast guardsmen working out of

the old lifesaving station around the bay. With the keeper's dwelling no

longer required, the structure along with all outbuildings were

demolished in the 1940's, leaving the forty-one foot tower standing

alone on Whiskey Point.

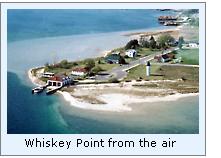

The lone tower still serves as an active aid

to navigation, welcoming visitors arriving on the island on the daily

ferries which run back and forth between the island and Charlevoix

during the summer months. In June 2004, the station was transferred to

St. James Township under the auspices of the the National Historic

Lighthouse Preservation Act. The township subsequently began a full

restoration of the tower.

Keepers of

this Light

Click Here to see a complete listing of

all Beaver Island Harbor Light keepers compiled by Phyllis L. Tag of

Great Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Seeing This Light

The Beaver Island Boat Company offers daily ferry trips from Charlevoix

out to Beaver Island Harbor, with up to four trips a day scheduled

during the busy summer weekends at a round-trip cost of approximately

$32.00 per person. For more information, contact them at:

Beaver Island Boat Company

103 Bridge Park Drive

Charlevoix, MI 49720

Phone: 231-547-2311

info@bibco.com

Or Click here

to visit the Beaver Island Boat Company website.

Reference Sources

Inventory of Historic Light Stations, National Parks Service, 1994.

USCG Historians office, Photographic archives.

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Board, Various 189-1903.

Northern Lights, Charles K. Hyde, 1995

02/24/01 email from Thomas A. Tag on McKindley's last day at the light.

Beaver Harbor Light, Beaver Island Net, website

A child of the sea - Life among the Mormons, Elizabeth

Whitney Williams, 1905

Women Who Kept The Lights, Candace Clifford, 1993

The life of Elizabeth Whitney Williams,

Michigan Educational Portal.

The lighthouses and lore of "America's Emerald Isle, Jeremy

D'Entremont, 1995

Keeper listings for this light appear courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|