|

Historical

Information

With the 1845 bonanza copper strike at the nearby Cliff Mine, the

natural harbor at Eagle River quickly boomed as the shipping point for

the mine's bounty. With a seemingly endless parade of vessels delivering

immigrant miners and supplies and shipping copper though the Sault locks

to the company's smelters in Pittsburgh, it was clear that an aid to

navigation was necessary to guide the growing vessel traffic safely into

the bustling harbor.

At the Fifth Auditor's recommendation, Congress appropriated the sum of

$4,000 for the construction of the Eagle

River Light Station in 1850, with the station illuminated four

years later.

Together, the Cliff Mine and Eagle River continued to flourish, with the

construction of huge stamping mills, warehouses, and streets lined

solidly with boarding houses, saloons and miner's homes to serve the

burgeoning population.

With every boom, there is an inevitable bust. Declining copper prices

slowed the Cliff Mine's output, and by the late 1860's Eagle River had

become a virtual ghost town. With the mine's closure in 1873, Eagle

River's once busy docks sat rotting, and without maritime traffic, the

river mouth became silted to a point that the harbor became inaccessible

to all but the shallowest draft vessels.

By 1890, virtually the only vessel making its way into the harbor was

the lighthouse tender on its annual supply trips, and the Lighthouse

Board was well aware of the futility of continuing to maintain a light

to protect a non-existent harbor.

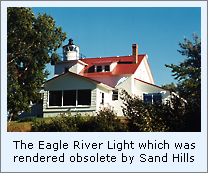

In its 1892 annual report, the Lighthouse Board noted that traffic

patterns on the lake had changed, and that eastbound vessels were making

a turn off Sand Hills, some twelve miles to the west of Eagle River, and

approximately midway between the coast lights of Ontonagon and Eagle Harbor. With the treacherous Sawtooth Reef located just offshore at this

point, the Board recommended to Congress that $20,000 be appropriated to

decommission the light at Eagle River, and construct a new coast light

at Sand Hills.

In its 1892 annual report, the Lighthouse Board noted that traffic

patterns on the lake had changed, and that eastbound vessels were making

a turn off Sand Hills, some twelve miles to the west of Eagle River, and

approximately midway between the coast lights of Ontonagon and Eagle Harbor. With the treacherous Sawtooth Reef located just offshore at this

point, the Board recommended to Congress that $20,000 be appropriated to

decommission the light at Eagle River, and construct a new coast light

at Sand Hills.

Congress responded with an act authorizing the construction of the new

station on February 15, 1893, but failed to make an appropriation for

the necessary funds. While the Board reiterated the need for the

appropriation in each of its' annual reports for the following seven

years, no moneys were forthcoming. Citing rising costs, in its 1899

annual report, the Board increased its estimate of the necessary funds

to $25,000, an amount which subsequently grew to $38,000 in its 1902

report, and yet Congress still failed to authorize the necessary funds.

The Board continued to request the $38,000 in every subsequent annual

report through 1907, when it finally abandoned the project, and ceased

to mention the planned station. The Eagle River Light Station was

decommissioned in 1908, and with no light between Ontonagon to Eagle

Harbor, mariners making their way along the coast were forced to run

blind at night.

With the elimination of the Lighthouse Board in 1910, responsibility for

the nation's lighthouses was transferred to George R. Putnam who was

appointed to the newly formed position of "Commissioner of

Lighthouses" under the Treasury Department. In his 1911 annual

report to Congress, Putnam again picked up the call for the elimination

of the Eagle River light, and the erection of a new light station at

Sand Hills. Reporting that ten vessels had stranded on Sawtooth Reef

over the past decade with resulting losses in excess of a million

dollars, Putnam's revised proposal for the Sand Hills light station

called for an appropriation of $75,000 for the construction of both a

coast light and fog signal station.

With the elimination of the Lighthouse Board in 1910, responsibility for

the nation's lighthouses was transferred to George R. Putnam who was

appointed to the newly formed position of "Commissioner of

Lighthouses" under the Treasury Department. In his 1911 annual

report to Congress, Putnam again picked up the call for the elimination

of the Eagle River light, and the erection of a new light station at

Sand Hills. Reporting that ten vessels had stranded on Sawtooth Reef

over the past decade with resulting losses in excess of a million

dollars, Putnam's revised proposal for the Sand Hills light station

called for an appropriation of $75,000 for the construction of both a

coast light and fog signal station.

Once again, the pleas for this station echoed unheeded through the halls

of Congress, and Putnam repeated his request in each of his subsequent

annual reports until Congress finally responded favorably with an

appropriation of $70,000 for the project on June 12, 1917.

Putnam acted quickly, with a forty-seven acre site selected, surveyed,

and purchased that summer. By the close of navigation for 1917,

contracts had been issued for virtually all of the materials required

for construction, the site had been cleared, and the concrete foundation

for the structure was poured. Putnam acted quickly, with a forty-seven acre site selected, surveyed,

and purchased that summer. By the close of navigation for 1917,

contracts had been issued for virtually all of the materials required

for construction, the site had been cleared, and the concrete foundation

for the structure was poured.

Work resumed the following spring, with the establishment of a temporary

lens-lantern light and electrically-operated fog signal. The work crew

then turned its attention to the simultaneous construction of both the

fog signal building and the lighthouse proper, which lasted through the

end of that year and into 1919.

The fog-signal building was erected on a solid concrete slab, with its

walls constructed of hollow tile with an exterior stucco coating. In

order to ensure that the fog signal would always be operational, a

redundant system of dual type

"F" diaphone fog signals with duplicate compressors

and oil engines was installed. Such a dual installation ensured that one

unit was always operational when maintenance was being performed on the

other. Each diaphone fed its signal through a cast iron

"trumpet" resonator protruding through the wall of the

building, which concentrated the sound and projected it seven miles

across the lake. Work on the fog-signal was completed in May 1919, and

was officially put into service on May 15.

The plans for the Sand Hills lighthouse were some of the most ambitious

ever proposed for a light station, and called for a combined yellow

brick light tower and triple dwelling, with the 70-foot tall tower

centered in the building. The tower itself was built around a steel

girder support system with concrete floors and a cast iron stairway, and

was designed as a self-contained fireproof central core to reduce the

chance of a fire in the tower spreading into the dwellings. The second

floor of the tower served as a central office, and each of the three

adjoining apartments had its own entrance into the tower. The plans for the Sand Hills lighthouse were some of the most ambitious

ever proposed for a light station, and called for a combined yellow

brick light tower and triple dwelling, with the 70-foot tall tower

centered in the building. The tower itself was built around a steel

girder support system with concrete floors and a cast iron stairway, and

was designed as a self-contained fireproof central core to reduce the

chance of a fire in the tower spreading into the dwellings. The second

floor of the tower served as a central office, and each of the three

adjoining apartments had its own entrance into the tower.

While directly connected to the tower, each apartment was constructed as

a separate entity, with all connecting walls being built of brick, once

again designed to stop the spread of a possible fire from one apartment

into an adjacent unit or into the tower.

Each apartment was outfitted with hardwood floors, with all interior

walls built of stud construction, and finished-out with hardwood trim

and doors. Each apartment sat on its own cellar, and surrounding central

basement which housed the equipment for the station's hot water central

heating and pneumatic water supply systems. The brick exterior of the

building was finished with cut stone balustrades and cornices, and the

roofs of each of the dwellings was sheathed with durable copper

sheeting. Each apartment was outfitted with hardwood floors, with all interior

walls built of stud construction, and finished-out with hardwood trim

and doors. Each apartment sat on its own cellar, and surrounding central

basement which housed the equipment for the station's hot water central

heating and pneumatic water supply systems. The brick exterior of the

building was finished with cut stone balustrades and cornices, and the

roofs of each of the dwellings was sheathed with durable copper

sheeting.

The tower was crowned with a cast iron deck and a prefabricated circular

cast-iron lantern of 7' 1" inside diameter furnished with curved

glass and diagonal astragals. The Fourth

Order Fresnel lens, manufactured by Henry-Lepaute of Paris was

mounted on a ball-bearing race and rotated by a standard clockwork

mechanism. Equipped with a 35 millimeter incandescent oil vapor lamp,

the lens was designed to rotate at a rate which would show a fixed light

with a characteristic flash every ten seconds, and by virtue of its 91

foot focal plane, was designed to be visible for a distance of 18 miles

in clear weather.

A concrete dock was constructed at the waters edge for the unloading of

supplies, and a tramway constructed from the dock to the station

buildings to facilitate the movement of supplies. A concrete dock was constructed at the waters edge for the unloading of

supplies, and a tramway constructed from the dock to the station

buildings to facilitate the movement of supplies.

Work on the lighthouse was completed in June of 1919, and Head Keeper

William Richard Bennetts exhibited the light for the first time on June

18 of that same year.

Sand Hills remained manned for only twenty years. In 1939, the Coast

Guard assumed responsibility for the nation's aids to navigation, and

automated the light with the installation of an acetylene lamp with

automatic sun valve, thus eliminating the costs associated with the

station's three keepers. With the closure of the station William

Bennetts retired from service, after having served as the station's sole

head keeper throughout all of its manned operation.

The station stood empty until 1942 when it was temporarily reopened as a

wartime Coast Guard training facility, in which guise it served as home

and school to over 200 trainees at a time. The buildings were closed and

locked the following year, and the station was once again went empty. The station stood empty until 1942 when it was temporarily reopened as a

wartime Coast Guard training facility, in which guise it served as home

and school to over 200 trainees at a time. The buildings were closed and

locked the following year, and the station was once again went empty.

In 1954, with improvements in weather forecasting and the adoption of

radar, it was determined that the light was no longer necessary. The

stationed was decommissioned and the Sand Hills name was forever removed

from the official listings of aids to navigation.

The lighthouse was turned over to the General Services Administration

for liquidation. Offered at public auction in 1958, the entire station

property was purchased for the princely sum of $26,00 by H. Donald

Bliss, and insurance agent from the Detroit area. Bliss and his family

used the structure as their private summer cottage for the next few

years. While it was reported that Bliss had plans to restore the

structure, they never came to fruition as the property was once again

offered for sale in 1961. The lighthouse was turned over to the General Services Administration

for liquidation. Offered at public auction in 1958, the entire station

property was purchased for the princely sum of $26,00 by H. Donald

Bliss, and insurance agent from the Detroit area. Bliss and his family

used the structure as their private summer cottage for the next few

years. While it was reported that Bliss had plans to restore the

structure, they never came to fruition as the property was once again

offered for sale in 1961.

Detroit photographer and artist Bill Frabotta purchased the station,

converting the fog signal building into a summer cottage where he and

his wife Eva spent the following 30 years walking the halls of the

station building planning their upcoming restoration. After a

comprehensive three year renovation undertaken between 1992 and 1995,

the building was reopened as one of the nation's premier bed and

breakfast inns.

Keepers of

this Light

Click here

to see a complete listing of all Sand Hills Light keepers compiled by

Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Seeing this Light

We have yet

to visit this light. However Larry Diegel, who is working with Bill

Frabotta in the restoration project, has been kind enough to photograph

the station and some of the historical photographs in Bill's station

archives for inclusion on our website. A big thanks to Larry and Bill

for sharing these images.

Finding this

Light

Follow Hwy. 41 North into the village of Ahmeek, and turn left at the

first street. Follow the signs directing you to Five Mile Point Road,

where you will then continue the eight miles to the lighthouse. There

are signs for the lighthouse along the road.

Contact

information

Sand Hills Lighthouse Inn

Five Mile Point Road P.O. Box 414

Ahmeek, MI 49901

(906) 337-1744

Click

here to visit

Bill Frabotta's Sand Hills Bed & Breakfast Inn web

site.

Reference

Sources

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Board, 1890 through 1910.

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Board, 1890 through 1910.

Annual reports of the Commissioner of Lighthouses, 1911 through 1929.

Annual reports of the Lake Carriers Association, 1909 through 1919.

Lake Superior, Grace Lee Nute, 1944, 1972

Contemporary Photographs courtesy of Larry Diegel.

Historic photographs courtesy Bill Frabotta's Sand Hills Lighthouse

Archives.

Ready for Lighthouse Keeping, Detroit News, 11/16/1958.

The Story of Sand Hills Light, H. Donald Bliss, 1960.

Keeper listings for this light appear

courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|