|

Historical Information

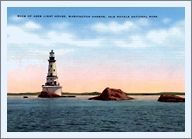

Consisting of a strip of exposed

rock 50 feet wide and 210 feet long, with it highest point some sixteen

feet above the water, Rock of Ages lies two and a half miles off the

western end of Isle Royale. While the 205-foot wooden sidewheel steamer

CUMBERLAND had been the rockís only victim in over a half century of

Superior navigation, changing navigation patterns in the final decade of

the nineteenth century suddenly made Rock of Ages a critical impediment

to safe navigation on the big lake.

As Duluth grew to preeminence as the lakeís major shipping port, a

growing number of mariners were choosing to set a course along the

northern shore during Superiorís violent storms in order to avoid the

uncertain and changeable conditions of open water. With Rock of Ages

lurking directly in the path of vessels choosing this course, a cry

arose in the maritime community for the establishment of a Light on Rock

of Ages. Concurring that the situation represented a disaster waiting to

happen, the Lighthouse Board first recommended that a Congressional

appropriation of $50,000 be made for construction of a Light and fog

signal on The Rock in its annual report for 1896. As Duluth grew to preeminence as the lakeís major shipping port, a

growing number of mariners were choosing to set a course along the

northern shore during Superiorís violent storms in order to avoid the

uncertain and changeable conditions of open water. With Rock of Ages

lurking directly in the path of vessels choosing this course, a cry

arose in the maritime community for the establishment of a Light on Rock

of Ages. Concurring that the situation represented a disaster waiting to

happen, the Lighthouse Board first recommended that a Congressional

appropriation of $50,000 be made for construction of a Light and fog

signal on The Rock in its annual report for 1896.

Congress ignored the request for of the following two years.

Surprisingly, even the loss of the 257-foot wooden-hulled propeller

HENRY CHISHOLM on Rock of Ages on October 20, 1898 did nothing to spur

action, and the Board continued to repeat its plea for funding on an

annual basis until 1900. Realizing that it had grossly underestimated

the cost for establishing a first class Light in such a desolate

location, the Board increased its estimate for construction to $125,000

in its annual report for 1900. With Congress continuing to turn a deaf

ear to its pleas, the Board decided to take a different tack in 1903,

and requested a lesser appropriation of $25,000 to fund a detailed

survey and examination of the site.

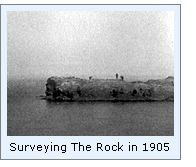

Congress finally responded with the requested appropriation on March

3, 1905, and a surveying and engineering team was dispatched to Rock of

Ages from Detroit that summer. On June 30, 1906, a second appropriation

of $50,000 was made, and congressional approval was given for the

construction of the new station provided that total construction costs

could be kept below a ceiling of $100,000. Agreeing with the budgetary

limitations, Eleventh District Engineer Major Charles Keller drew up

detailed plans and specifications for the new station over the winter of

1906 - 1907. Plans for the new tower borrowed heavily from current state

of the art construction methods in use in skyscraper construction, with

a central structural steel skeleton structure supporting masonry tower

floors and walls. As an indicator of the importance placed on this new

station, Keller's plans called for the tower to be capped by a massive

Second Order Fresnel lens. With an appropriation of the remaining $50,000 on

March 4, 1907, construction of the new station was completely funded,

and Keller awarded contracts for supplying the necessary building

materials, with the contract for the towerís steel skeleton support

structure awarded to the Russell Wheel and Foundry Company of Detroit. Congress finally responded with the requested appropriation on March

3, 1905, and a surveying and engineering team was dispatched to Rock of

Ages from Detroit that summer. On June 30, 1906, a second appropriation

of $50,000 was made, and congressional approval was given for the

construction of the new station provided that total construction costs

could be kept below a ceiling of $100,000. Agreeing with the budgetary

limitations, Eleventh District Engineer Major Charles Keller drew up

detailed plans and specifications for the new station over the winter of

1906 - 1907. Plans for the new tower borrowed heavily from current state

of the art construction methods in use in skyscraper construction, with

a central structural steel skeleton structure supporting masonry tower

floors and walls. As an indicator of the importance placed on this new

station, Keller's plans called for the tower to be capped by a massive

Second Order Fresnel lens. With an appropriation of the remaining $50,000 on

March 4, 1907, construction of the new station was completely funded,

and Keller awarded contracts for supplying the necessary building

materials, with the contract for the towerís steel skeleton support

structure awarded to the Russell Wheel and Foundry Company of Detroit.

In order to support such a difficult offshore construction site,

Kellerís plans called for the establishment of a base station in

Washington Harbor on Isle Royale using a number of leased abandoned

mining buildings at the head of the harbor. Here, supplies could be

stored, components prefabricated, and quarters for the work crew

established until work on The Rock had progressed to a point at which

quarters could be established on the rock itself. A chartered steam

barge loaded with materials left the Detroit Depot on May 21, 1908

arriving in Washington Harbor on May 27. After erecting a pair of

landing wharves, installing a tramway to transport materials and the

rehabilitation of the old mining structures, a 50-man work crew was

dispatched to begin work on The Rock itself.

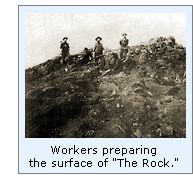

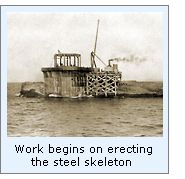

Construction on the Rock began with a small crew of quarrymen

delivered to the site, where they set about the task of blasting of a

flat section at the west end of the rock mass to a level of

approximately two feet above the water level. With site preparation

completed in June, a circular pier with walls of heavy riveted steel

plates standing fifty feet in diameter was erected. Standing twenty-five

feet in height, the upper walls flared out in a graceful curve to 56

feet in diameter at the top in order to form a wave deflector. With

completion of the pier walls, a sturdy timber platform was erected and

attached to the east side of the pier to serve as a working area from

the work crew could begin the process of filling the pier casing with

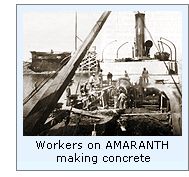

concrete. The lighthouse tender AMARANTH, her holds loaded with gravel

and cement, arrived at the site and anchored in deep water just off the

Rock. Using a large cement mixer on her deck, a crew set about mixing

innumerable loads of concrete and transferring them by boom to a scow

for transport to the Rock, where the construction crew poured

innumerable layers within the circular pier. As the concrete level

within the pier rose, forms were placed at its center to create a

two-story cellar lined with porous tile. At the very center of these

cellars, a steel column was integrated with its lower end lagged into a

footing in the floor of the lower cellar. This column was to serve as

the central core of the steel skeleton, and as such was designed to

transfer the load of the entire structure directly down to the bedrock

below. Construction on the Rock began with a small crew of quarrymen

delivered to the site, where they set about the task of blasting of a

flat section at the west end of the rock mass to a level of

approximately two feet above the water level. With site preparation

completed in June, a circular pier with walls of heavy riveted steel

plates standing fifty feet in diameter was erected. Standing twenty-five

feet in height, the upper walls flared out in a graceful curve to 56

feet in diameter at the top in order to form a wave deflector. With

completion of the pier walls, a sturdy timber platform was erected and

attached to the east side of the pier to serve as a working area from

the work crew could begin the process of filling the pier casing with

concrete. The lighthouse tender AMARANTH, her holds loaded with gravel

and cement, arrived at the site and anchored in deep water just off the

Rock. Using a large cement mixer on her deck, a crew set about mixing

innumerable loads of concrete and transferring them by boom to a scow

for transport to the Rock, where the construction crew poured

innumerable layers within the circular pier. As the concrete level

within the pier rose, forms were placed at its center to create a

two-story cellar lined with porous tile. At the very center of these

cellars, a steel column was integrated with its lower end lagged into a

footing in the floor of the lower cellar. This column was to serve as

the central core of the steel skeleton, and as such was designed to

transfer the load of the entire structure directly down to the bedrock

below.

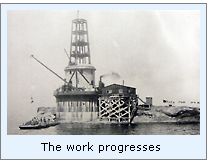

With the surface of the pier complete, and thus able to serve as a

work platform for the continuing construction of the tower, a large

bunkhouse was erected on the timber platform, and the construction crew

was able to live on the Rock on a full time basis. With daily trips to

and from the Rock no longer necessary and work progressed at an

increased rate, and the skeletal steel core of the structure began to

rise quickly. With the surface of the pier complete, and thus able to serve as a

work platform for the continuing construction of the tower, a large

bunkhouse was erected on the timber platform, and the construction crew

was able to live on the Rock on a full time basis. With daily trips to

and from the Rock no longer necessary and work progressed at an

increased rate, and the skeletal steel core of the structure began to

rise quickly.

Work continued through the 1908 season of navigation until all

brickwork and masonry was complete, the main deck was fitted-out, the

service room and lantern installed, and installation of the stationís

mechanical systems, including the steam heating plant, fog signal

equipment and water storage tanks was underway. With the glazing of the

lantern complete, a temporary fixed red Third Order Fresnel lens

was

installed and a single six-inch air operated fog siren placed into

operation on the night of October 22. Thomas Ervine was appointed as the

stationís first Head Keeper, however Second Assistant William Duggan

was first to report for duty at the station on October 2, with Irvine

and First Assistant Lee Benton arriving together on October 27. Keeper

Irvine was an eight-year lighthouse service veteran, with previous

assignments at Outer Island and Au Sable Point, the latter of which was

likely considered to have prepared him well for duty at a remote station

such as Rock of Ages. With construction crew members available to lend

assistance as needed, the Third Assistant Keeper position would remain

unfilled until January, 1910. As violent storms began sweeping through

the area, the station was closed on November 4, 1908, and construction

ended until improved weather conditions allowed resumption of work the

following year.

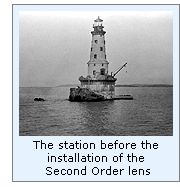

With insufficient funding available in the $100,000 total

appropriation to allow the purchase of the permanent Second

Order Fresnel lens lens for the station,

Congress appropriated an additional $15,000 for a new lens on March 4.

Responsibility for specifying and ordering the new lens was delegated to

the Chief Engineer of the Third Lighthouse District, and an order for

the lens was placed with Parisian lens manufacturer Barbier, Benard

& Turenne on March 26. With insufficient funding available in the $100,000 total

appropriation to allow the purchase of the permanent Second

Order Fresnel lens lens for the station,

Congress appropriated an additional $15,000 for a new lens on March 4.

Responsibility for specifying and ordering the new lens was delegated to

the Chief Engineer of the Third Lighthouse District, and an order for

the lens was placed with Parisian lens manufacturer Barbier, Benard

& Turenne on March 26.

Back on Lake Superior, work resumed at the Rock in early 1909.

Between July 1 and August 31 all of the stationís interior work was

installed and painted, the pier surface paved, a chain railing installed

around the outer perimeter of the pier, and a permanent 11 foot by 24

foot landing crib erected.

On completion, the tower stood eight stories in height, and offered

relatively large and comfortable quarters for the complement of four

keepers assigned to the station. A steam heating plant located in the

upper cellar provided heat to cast iron radiators in all rooms, and the

first deck was home to the fog signal plant and hoisting engines for the

pillar crane located at the edge of the pier level. This crane was used

both for raising supplies delivered by the lighthouse tenders at the

wharf and for raising the keeperís boat for storage on the safety of

the pier deck. An office and common room made up the second deck, and a

mess room and kitchen the third. The Keeper and First Assistantís

quarters were located on the fourth deck, with the Second and Third

Assistants quarters immediately above on the Fifth deck. A service room

and watch room comprised the sixth and seventh decks, leaving the huge

lantern capping the structure above. On completion, the tower stood eight stories in height, and offered

relatively large and comfortable quarters for the complement of four

keepers assigned to the station. A steam heating plant located in the

upper cellar provided heat to cast iron radiators in all rooms, and the

first deck was home to the fog signal plant and hoisting engines for the

pillar crane located at the edge of the pier level. This crane was used

both for raising supplies delivered by the lighthouse tenders at the

wharf and for raising the keeperís boat for storage on the safety of

the pier deck. An office and common room made up the second deck, and a

mess room and kitchen the third. The Keeper and First Assistantís

quarters were located on the fourth deck, with the Second and Third

Assistants quarters immediately above on the Fifth deck. A service room

and watch room comprised the sixth and seventh decks, leaving the huge

lantern capping the structure above.

Manufacturing of the new lens was completed in early 1910, and the

lens was crated for shipment from Paris to the main lighthouse depot on

Staten Island that summer. After receipt of the lens at the Detroit

depot, the Eleventh District Lampist loaded the crates aboard the

AMARANTH, arriving at Rock of Ages in early September. The Lampist

uncrated the cast iron pedestal and hoisted it into the mechanical room

below the lantern. The lens itself was designed with four lightning

flash panels, each consisting of 7 refracting and 17 reflecting prisms,

and was floated atop the pedestal on a bath of mercury, designed to

virtually eliminate rotational friction. Turned by a clockwork

mechanism, the Lampist carefully adjusted the rotation speed of the

massive lens to ensure that the stationís designated characteristic of

a double flash every ten seconds was matched perfectly. Illuminated by a

double-tank incandescent oil vapor lamp, the double flashes emitted a

remarkable 940,000 candlepower, and by virtue of its situation at a

focal plane of 117 feet, the lens boasted a visible range of nineteen

miles on the night of its initial exhibition on September 15, 1910. Manufacturing of the new lens was completed in early 1910, and the

lens was crated for shipment from Paris to the main lighthouse depot on

Staten Island that summer. After receipt of the lens at the Detroit

depot, the Eleventh District Lampist loaded the crates aboard the

AMARANTH, arriving at Rock of Ages in early September. The Lampist

uncrated the cast iron pedestal and hoisted it into the mechanical room

below the lantern. The lens itself was designed with four lightning

flash panels, each consisting of 7 refracting and 17 reflecting prisms,

and was floated atop the pedestal on a bath of mercury, designed to

virtually eliminate rotational friction. Turned by a clockwork

mechanism, the Lampist carefully adjusted the rotation speed of the

massive lens to ensure that the stationís designated characteristic of

a double flash every ten seconds was matched perfectly. Illuminated by a

double-tank incandescent oil vapor lamp, the double flashes emitted a

remarkable 940,000 candlepower, and by virtue of its situation at a

focal plane of 117 feet, the lens boasted a visible range of nineteen

miles on the night of its initial exhibition on September 15, 1910.

Life at Rock of Ages settled into a regular routine. With four

keepers assigned to the station, a regular rotating schedule was

established through which one of the keepers was scheduled for a weekís

leave every month. Free time at the station was spent in reading,

playing cards, or fishing around the Rock. The establishment of a

radiobeacon at the station in 1929 forced the keepers to quickly

acquaint themselves with electronics, and was likely a source of

frequent problem, as the early equipment proved to be unreliable and

prone to frequent breakdowns. 1930 saw the electrification of the

station through the installation of electric generators powered by

diesel engines, and electrification in turn paved the way for the

replacement of the single air siren with a pair of Tyfon fog signals in

1931. In order to provide the widest possible range of dispersion, the

horns for these signals were mounted on opposing sides of the tower.

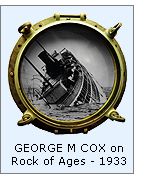

In a foggy May 28th in 1933, with the fog signal screaming out across

the lake, Keeper John F. Soldenski stood watch in watch room to keep an

eye out for approaching vessels. Imagine his surprise and he watched as

a the 259-foot passenger vessel GEORGE M COX came lumbering out of the

fog at seventeen knots, heard the horn, and turned directly into the

Reef. The COX had been built as PURITAN in 1901, and had recently been

refitted as a luxury liner, and renamed after the Shipping Magnate who

had commissioned the refit. As such, she was on her maiden voyage from

Chicago to Port Arthur, with a stop in Houghton. Onboard were 125

crewmembers, company dignitaries and their friends. In a foggy May 28th in 1933, with the fog signal screaming out across

the lake, Keeper John F. Soldenski stood watch in watch room to keep an

eye out for approaching vessels. Imagine his surprise and he watched as

a the 259-foot passenger vessel GEORGE M COX came lumbering out of the

fog at seventeen knots, heard the horn, and turned directly into the

Reef. The COX had been built as PURITAN in 1901, and had recently been

refitted as a luxury liner, and renamed after the Shipping Magnate who

had commissioned the refit. As such, she was on her maiden voyage from

Chicago to Port Arthur, with a stop in Houghton. Onboard were 125

crewmembers, company dignitaries and their friends.

Soldenski and his assistants Whipple, Marshall and Marrow managed to

rescue all 125 crew and passengers, with all of them forced to spend the

night crammed into the tight quarters of the lighthouse, many of them

sitting on the spiral stairs. While the Portage lifeboat arrived late

that night and took of a few of the injured passengers, it was not until

the following day that the Coast Guard Cutter CRAWFORD arrived to take

the remainder of the marooned passengers to the safety of shore in Two

Harbors, Minnesota. While the Cox was the only wreck to occur on The

Rock after the establishment of the lighthouse, it was not the only

tragedy that would be associated with the station.

I n the summer of 1939, the lighthouse tender AMARANTH had been

dispatched to Rock of Ages to replace one of the stationís aging

Fairbanks Morse air compressors with a new unit. The tender carefully

approached the Light Station and dropped anchor in deep water a short

distance from the station. A steel scow had been lowered into the water

by the tenderís boom, and the new compressor lowered onto the scow,

and powered by the tenderís launch, towed to the wharf alongside the

lighthouse. From there, the stationís steam winch had been used to

lift the new compressor onto the stationís main deck. The old

compressor had in turn been lowered onto the scow, and the launch was in

the process of returning to the AMARANTH with the old compressor. As the

scow approached the tender it became clear that the launch was making a

little too much headway, and the scow smashed into tenderís massive

hull. The inertia caused the heavy compressor to slide across the scowís

smooth deck, with the sudden load shift causing the scow to upend. A

couple of deckhands on the scow managed to jump from the scow to the

deck of the tender at the last second as the upended gunwale of the scow

smashed against the tenderís hull. Unfortunately, deckhand Robert

"Sonny" Bergmarker was less fortunate, ending up with his

lower body crushed between the scow and the tenderís hull. Crewmen

quickly hoisted Bergearker aboard the tender where first aid was

administered, however it was clear that Bergearker needed to get to a

hospital as soon as possible if he was to stand a chance of survival.

Quickly hoisting the scow and launch back onto the tenderís deck,

Captain OíDonnell ordered a full head of steam, and the venerable

tender headed for the nearest hospital in Houghton. The tenderís coal

passers worked at a feverish pitch to get their shipmate to the hospital

as quickly as possible. However, Bergearker sadly passed away before

they could get him into the hospital. n the summer of 1939, the lighthouse tender AMARANTH had been

dispatched to Rock of Ages to replace one of the stationís aging

Fairbanks Morse air compressors with a new unit. The tender carefully

approached the Light Station and dropped anchor in deep water a short

distance from the station. A steel scow had been lowered into the water

by the tenderís boom, and the new compressor lowered onto the scow,

and powered by the tenderís launch, towed to the wharf alongside the

lighthouse. From there, the stationís steam winch had been used to

lift the new compressor onto the stationís main deck. The old

compressor had in turn been lowered onto the scow, and the launch was in

the process of returning to the AMARANTH with the old compressor. As the

scow approached the tender it became clear that the launch was making a

little too much headway, and the scow smashed into tenderís massive

hull. The inertia caused the heavy compressor to slide across the scowís

smooth deck, with the sudden load shift causing the scow to upend. A

couple of deckhands on the scow managed to jump from the scow to the

deck of the tender at the last second as the upended gunwale of the scow

smashed against the tenderís hull. Unfortunately, deckhand Robert

"Sonny" Bergmarker was less fortunate, ending up with his

lower body crushed between the scow and the tenderís hull. Crewmen

quickly hoisted Bergearker aboard the tender where first aid was

administered, however it was clear that Bergearker needed to get to a

hospital as soon as possible if he was to stand a chance of survival.

Quickly hoisting the scow and launch back onto the tenderís deck,

Captain OíDonnell ordered a full head of steam, and the venerable

tender headed for the nearest hospital in Houghton. The tenderís coal

passers worked at a feverish pitch to get their shipmate to the hospital

as quickly as possible. However, Bergearker sadly passed away before

they could get him into the hospital.

That same year, President Franklin Roosevelt decided to eliminate the

Bureau of Lighthouses, and placed responsibility for the nationís aids

to navigation under the umbrella of the Coast Guard. The Bureau Keepers

were given a choice of either maintaining their civilian status, or

entering the Coast Guard, and approximately 50% of the old Wickies made

the switch to military life. Bill Muessel was one of those who chose to

make the change. After entering lighthouse service early in 1939, Bill

had served six years on the AMARANTH and TAMARACK before spending a year

at Outer Island and a second year on Passage Island. After graduation

from Aids to Navigation school in Groton, Connecticut, he was assigned

as Officer in Charge at Rock of Ages in 1949, in which capacity he

served until 1954. I was fortunate to be able to interview Bill in June

2002, and he gave me some wonderful memories of his time on The Rock.

Click here to read a complete transcript of my interview with Bill. That same year, President Franklin Roosevelt decided to eliminate the

Bureau of Lighthouses, and placed responsibility for the nationís aids

to navigation under the umbrella of the Coast Guard. The Bureau Keepers

were given a choice of either maintaining their civilian status, or

entering the Coast Guard, and approximately 50% of the old Wickies made

the switch to military life. Bill Muessel was one of those who chose to

make the change. After entering lighthouse service early in 1939, Bill

had served six years on the AMARANTH and TAMARACK before spending a year

at Outer Island and a second year on Passage Island. After graduation

from Aids to Navigation school in Groton, Connecticut, he was assigned

as Officer in Charge at Rock of Ages in 1949, in which capacity he

served until 1954. I was fortunate to be able to interview Bill in June

2002, and he gave me some wonderful memories of his time on The Rock.

Click here to read a complete transcript of my interview with Bill.

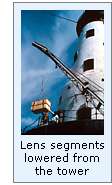

The massive Second Order lens was removed from the lantern over a

five day period in 1985, and a 12-volt DC solar-powered 300 mm optic

installed in its place. The intricate Fresnel was reassembled and placed

on display at the Windigo Ranger Station in Washington Harbor some five

miles away. The massive Second Order lens was removed from the lantern over a

five day period in 1985, and a 12-volt DC solar-powered 300 mm optic

installed in its place. The intricate Fresnel was reassembled and placed

on display at the Windigo Ranger Station in Washington Harbor some five

miles away.

To this day, the Cox stills sits teetering on the edge of Rock of

Ages Reef, and is a popular site for sport divers. On the shallow side

of the reef, her bow wreckage sits in 15 ft of water, while at a depth

of 45 feet, her two boilers can be seen, and her stern lies keel-up

between a depth of 50 and 90 feet. Both her screw and drive shaft are

still intact.

The Rock of Ages station is now part of Isle Royale Park, and because

landing at the dock is considered a dangerous proposition, the structure

is not open to the public. However, the 300 mm optic still beams from

the lantern every night, and the station still serves as an active aid

to navigation.

Keepers of

this Light

Click here

to see a complete listing of all Rock of Ages Light keepers compiled by

Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Seeing this Light

Keweenaw Excursions offers a lighthouse

cruise which passes Rock of Ages on board the KEWEENAW STAR out of

Houghton, Michigan. For more information on any of their tours visit

their website,

or telephone Keweenaw Excursions at (906) 482-0884.

Reference

Sources

Annual reports of the Lighthouse

Board, various, 1896 - 1912

Great Lakes Light Lists, various, 1917 - 1961

Great Lakes Pilot, 1958, US Army Corps of Engineers

Telephone interview with Bill Muessel, 6/2/2002

Email correspondence with Don Nelson, various, 2002

Wreck SCUBA Diving, Isle Royale, Lake Superior, website.

Keeper listings for this light appear

courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|