|

Historical Information

Finding the atmospheric conditions in Chicago to be deleterious to his

health, Ransom Shelden moved to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula in 1845,

where he and his brother-in-law Columbus C. Douglas established a

trading post at L’Anse. Relocating the business to the mouth of the

Portage River in the Spring of 1847, they augmented their mercantile

operations by establishing a flourishing fishing business. Over 1849 and

1850 they explored the area along the river, and finding large copper

deposits, incorporated the Portage, Isle Royale and Huron mining

Companies on 55,000 acres of land purchased from the Federal government.

In 1851 they moved operations inland, established a mining supply and

general store and platted the village of Houghton in the spring of 1853.

While the copper was desperately needed in the industrial centers on

lakes Erie and Michigan, Superior was virtually isolated from the lower

lakes by the St. Mary’s River rapids. Down-bound shipments arriving at

Sault Ste. Marie had to be offloading and transportation around the

rapids for reloading onto vessels at their lower end. A shrewd

businessman, Shelden foresaw the incredible impact the 1854 opening of

the first lock at the Soo would have on the mines of the Keweenaw, and

began pressuring federal representatives for the establishment of a

lighthouse to guide mariners to the entrance of the Portage river. While the copper was desperately needed in the industrial centers on

lakes Erie and Michigan, Superior was virtually isolated from the lower

lakes by the St. Mary’s River rapids. Down-bound shipments arriving at

Sault Ste. Marie had to be offloading and transportation around the

rapids for reloading onto vessels at their lower end. A shrewd

businessman, Shelden foresaw the incredible impact the 1854 opening of

the first lock at the Soo would have on the mines of the Keweenaw, and

began pressuring federal representatives for the establishment of a

lighthouse to guide mariners to the entrance of the Portage river.

Taking up Shelden’s call, Michigan Senator Alpheus Felch presented a

petition on behalf of Shelden and other area maritime interests before

the Senate on February 17, 1853 "praying for the erection of a

light-house at the mouth of Portage river." Te matter was referred to

the Committee on Commerce for further analysis, and evidently agreement

for the project was quickly obtained, as a $5,000 appropriation for the

new aid to navigation was approved by Congress a month later on March 3.

Soon after, a 57 acre reservation of federally owned land hand near the

river mouth had been arranged, Milwaukee builders Sweet, Ranson, and

Shinn were awarded the construction contract on July 17, 1854.

Construction was reported as being underway on the opening of the 1855

navigation season, with expectations that the work would be completed by

the end of the 1855 navigation season.

Over the summer of 1855, the new station took shape in the form of a

free-standing rubble stone tower and small detached dwelling. The

cylindrical tower walls stood 2’ 10" in thickness at the base and

tapered to 2’ 3" in thickness at the gallery. Atop this tower, an

octagonal wooden lantern 4’ 6" in diameter was installed, and reached by a

series of wooden steps within the tower. On completion, the structure

stood 39 feet in height from foundation to the top of the vent ball. Over the summer of 1855, the new station took shape in the form of a

free-standing rubble stone tower and small detached dwelling. The

cylindrical tower walls stood 2’ 10" in thickness at the base and

tapered to 2’ 3" in thickness at the gallery. Atop this tower, an

octagonal wooden lantern 4’ 6" in diameter was installed, and reached by a

series of wooden steps within the tower. On completion, the structure

stood 39 feet in height from foundation to the top of the vent ball.

Housed within the diminutive lantern, a

Fifth Order

Fresnel lens manufactured by Henry LePaute in Paris exhibited a

fixed white characteristic interrupted by a single white flash every

minute. While the lens consisted of four fixed 90 degree panels and did

not rotate, a pair of bulls eye flash panel were attached on opposite

sides of a frame which encircled the lens. Driven directly by a

clockwork motor, the frame made a complete revolution every two minutes,

placing one of the bulls eyes between the eye of an observer and the

light source, thereby imparting the light’s designated characteristic.

The detached 1 ½-story rubble stone dwelling to the north of the tower

stood 29 feet by 28 feet in plan with a 10 foot by 12 foot summer

kitchen attached to the rear gable end.

Construction was completed late in 1855, and in accordance with the

contract, the station buildings were submitted to the district inspector

for his approval. According to the 1857 Lighthouse Board annual report,

acceptance was refused, due to the fact that the buildings were "not

built in conformity to the terms of the contract." Under normal

circumstances, such a rejection would cause the station to remain

inactive until necessary repairs or adjustments were undertaken.

However, in the case of the Portage River light, even though the

deficiencies remained unresolved, Michael W Lyons was appointed to the

position of Keeper of the new Portage River light station on September

10, 1956, and exhibited his light soon thereafter.

With the matter of the station’s acceptability still unresolved in

1858, Secretary of the Treasury Howell Cobb reported that he would

dispatch an independent agent to Portage River on the opening of the

following navigation season to review the situation and determine a

go-forward plan. What arrangements were made have yet to be discerned,

as no further mention of the dispute appears in Lighthouse Board

documents subsequent to this year. As such, whether Sweet, Ranson and

Shinn were forced to undertake repairs at the station or whether they

ever received payment for the original construction has yet to be

determined. With the matter of the station’s acceptability still unresolved in

1858, Secretary of the Treasury Howell Cobb reported that he would

dispatch an independent agent to Portage River on the opening of the

following navigation season to review the situation and determine a

go-forward plan. What arrangements were made have yet to be discerned,

as no further mention of the dispute appears in Lighthouse Board

documents subsequent to this year. As such, whether Sweet, Ranson and

Shinn were forced to undertake repairs at the station or whether they

ever received payment for the original construction has yet to be

determined.

In 1865, a protective pier was erected at the river mouth, and to

better mark its location for vessels entered the river, a post lantern

was erected at its outer end. Since the existing light station was a

mere fifteen-minute walk from the pier, tending of this new light was

added to the responsibilities of then Portage River keeper Samuel

Stevenson. To help cover the resulting additional workload and

inconvenience, Stevenson’s pay was increased by $200 a year.

By 1868, the nature of the problems with the original construction of

the Portage River station became clear, when in his annual report for

that year the District Inspector reported that he found the buildings to

be in "dilapidated condition." He went on to say that the wooden lantern

was altogether too small for the lens, leaked badly, and water had so

permeated the tower that the wooden stairs were decayed and mortar was

being washed from between the stone. He also reported that there was no

overhang on the dwelling roof, standing water on the cellar floor, all

of the floors in the building were rotten to the point that they were

unsafe, and that the majority of the plaster had fallen from the

ceilings and walls. Overall, he determined that the tower was in such

bad condition that he recommended a special appropriation to fund the

installation of a new brick lining within the tower, the installation of

an iron stairway and lantern floor, and the erection of a standard sized

Fourth Order lantern. Determining that the dwelling had deteriorated

beyond repair, he further recommended that the entire structure be

demolished and a new dwelling erected and connected to the rebuilt tower

by a covered way. By 1868, the nature of the problems with the original construction of

the Portage River station became clear, when in his annual report for

that year the District Inspector reported that he found the buildings to

be in "dilapidated condition." He went on to say that the wooden lantern

was altogether too small for the lens, leaked badly, and water had so

permeated the tower that the wooden stairs were decayed and mortar was

being washed from between the stone. He also reported that there was no

overhang on the dwelling roof, standing water on the cellar floor, all

of the floors in the building were rotten to the point that they were

unsafe, and that the majority of the plaster had fallen from the

ceilings and walls. Overall, he determined that the tower was in such

bad condition that he recommended a special appropriation to fund the

installation of a new brick lining within the tower, the installation of

an iron stairway and lantern floor, and the erection of a standard sized

Fourth Order lantern. Determining that the dwelling had deteriorated

beyond repair, he further recommended that the entire structure be

demolished and a new dwelling erected and connected to the rebuilt tower

by a covered way.

After reviewing the magnitude of the repairs required, the decision

was made to completely rebuild both buildings to current Lighthouse

Board standards, and to this end a work crew and necessary materials

were delivered to begin the work in 1869. After erecting a temporary

structure from which to display the light, the tower and dwelling were

demolished and construction of the new buildings began. After reviewing the magnitude of the repairs required, the decision

was made to completely rebuild both buildings to current Lighthouse

Board standards, and to this end a work crew and necessary materials

were delivered to begin the work in 1869. After erecting a temporary

structure from which to display the light, the tower and dwelling were

demolished and construction of the new buildings began.

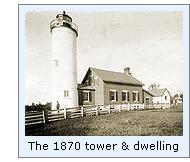

The new cylindrical tower was constructed of locally quarried

sandstone, and tapered from 12 feet in diameter at the foundation to 8

feet in diameter beneath the gallery. The tower was of double wall

construction, with the tapered outer wall standing 36" in thickness at

the base and the cylindrical inner wall 4" in thickness. The dual walls

were separated by an open space through which air could rise from vents

near the foundation, flowing upward through the structure to exit

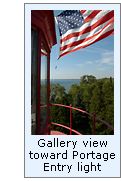

through the vent ball atop the lantern. Centered atop the circular

gallery, a standard prefabricated decagonal Fourth Order lantern of 84

½" diameter was installed with its vent ball standing 51’ above the

tower foundation.

To the north of the tower, a 1 ½-story brick dwelling containing 8

rooms was erected and connected to the tower by a covered way 10’ 6" in

length. An iron door at the tower end led to the spiral stairs wound

within the inner brick cylinder of the tower, and provided access to the

lantern through a scuttle door in the lantern’s ¾" thick iron floor.

While the 1869 annual report indicated that the tower was erected and

the dwelling was ready for plaster at the end of July, the station was

not finished until late in the navigation season. Thus, the light was

not displayed from atop the new tower until the opening of the 1870

navigation season, after the District Lampist arrived from Detroit and

transferred the Fifth Order lens from the temporary structure to a cast

iron pedestal centered within the lantern. Without any change in its

characteristic, the lens sat at a focal plane of 86 feet by virtue of

the tower’s location atop the bluff. To the north of the tower, a 1 ½-story brick dwelling containing 8

rooms was erected and connected to the tower by a covered way 10’ 6" in

length. An iron door at the tower end led to the spiral stairs wound

within the inner brick cylinder of the tower, and provided access to the

lantern through a scuttle door in the lantern’s ¾" thick iron floor.

While the 1869 annual report indicated that the tower was erected and

the dwelling was ready for plaster at the end of July, the station was

not finished until late in the navigation season. Thus, the light was

not displayed from atop the new tower until the opening of the 1870

navigation season, after the District Lampist arrived from Detroit and

transferred the Fifth Order lens from the temporary structure to a cast

iron pedestal centered within the lantern. Without any change in its

characteristic, the lens sat at a focal plane of 86 feet by virtue of

the tower’s location atop the bluff.

Copper was not the only geological attribute to play a key role in

the development of the area of the entrance to the Portage river. A

large section of the southern shore of the Keweenaw Peninsula was formed

from of a rich red sandstone, and in 1884, Marquette resident John H.

Jacobs established a number of quarries in the area. As Finnish stone

cutters and laborers moved in to the area to work the quarries, the

community of Jacobsville grew up around the lighthouse, from which the

red sandstone ended up taking its common name of Jacobsville sandstone. Copper was not the only geological attribute to play a key role in

the development of the area of the entrance to the Portage river. A

large section of the southern shore of the Keweenaw Peninsula was formed

from of a rich red sandstone, and in 1884, Marquette resident John H.

Jacobs established a number of quarries in the area. As Finnish stone

cutters and laborers moved in to the area to work the quarries, the

community of Jacobsville grew up around the lighthouse, from which the

red sandstone ended up taking its common name of Jacobsville sandstone.

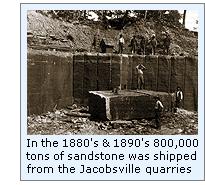

Over the 1800’s, many of the most important buildings in Houghton and

Marquette were built of sandstone from the Jacobsville quarries, and

word of the beauty of the red stone spread rapidly. Architects

throughout North America began specifying Jacobsville sandstone as the

material for new buildings in locations as far-flung as Hot Springs,

Omaha, New York and Montreal. Arguably, the most notable of such

structures built of stone shipped from the Jacobsville quarries was New

York’s magnificent Waldorf Astoria hotel, which was commissioned by

financier William Waldorf Astor in 1893, and sat on the current site of

the Empire State building.

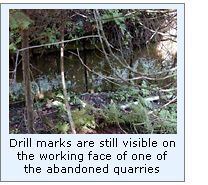

With the close of the 1890’s, tastes in building design began to

swing away from the dark, somber coloration of Victorian style

architecture, turning instead toward the lighter hues of limestone and

steel reinforced concrete. As such, Jacobsville sandstone grew out of

favor, and by the end of the first decade of the twentieth century the

Jacobsville quarries had all closed. In the short twenty years of their

prominence, over 800,000 tons of stone with a value in excess of

$8,000,000 had been shipped from the quarries located within a stone’s

throw from the gallery of the Portage River lighthouse. With the close of the 1890’s, tastes in building design began to

swing away from the dark, somber coloration of Victorian style

architecture, turning instead toward the lighter hues of limestone and

steel reinforced concrete. As such, Jacobsville sandstone grew out of

favor, and by the end of the first decade of the twentieth century the

Jacobsville quarries had all closed. In the short twenty years of their

prominence, over 800,000 tons of stone with a value in excess of

$8,000,000 had been shipped from the quarries located within a stone’s

throw from the gallery of the Portage River lighthouse.

In 1919, construction began on the new Keweenaw Waterway light on the

outer end of the east pier at the river entrance a mile to the west of

the Portage River lighthouse. Work on the new station was completed in

July of the following year, and the light exhibited for the first time

on the night of August 1, 1920. With the establishment of this new

light, the Portage River light was no longer necessary, and was

decommissioned with the establishment of the new light, and Keeper

Franklin W. Witz was transferred as keeper of the new station.

With the old light station and grounds no longer needed for

lighthouse purposes, the property was transferred to the State of

Michigan to be used for the creation of a park on August 10, 1932.

However, the State of Michigan never moved on creating the park and the

old station reverted to the Coast Guard on October 29, 1948. With the

Coast Guard having no use for the property, it was turned over to the

General Services Administration for liquidation. As a result, the

property was sold at auction on November 25, 1958 for the sum of $18,251

to Joynt Automotive of Alma. With the old light station and grounds no longer needed for

lighthouse purposes, the property was transferred to the State of

Michigan to be used for the creation of a park on August 10, 1932.

However, the State of Michigan never moved on creating the park and the

old station reverted to the Coast Guard on October 29, 1948. With the

Coast Guard having no use for the property, it was turned over to the

General Services Administration for liquidation. As a result, the

property was sold at auction on November 25, 1958 for the sum of $18,251

to Joynt Automotive of Alma.

Since that original sale, the historic property has changed hands,

but still remains in private hands.

Keepers of this

Light

Click here

to see a complete listing of all Portage River Light keepers compiled by

Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Seeing this

Light

Since the Portage River Light is now a private dwelling, and is

largely surrounded by other private property, we do not feel it would be ethical

to give specific directions to the light station.

Reference Sources

Annual reports of the

Lighthouse Board, various, 1854 –1909

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Service, various 1910 – 1920

Great Lakes Light Lists, various, 1856 – 1920

Journal of the US Senate, February 17, 1853

USLHS Form 40 inspection report of the station, 1910

History of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, 1883

The Keweenaw Waterway, Clarence J Monette, 1980

Rocks and Minerals of Michigan, Michigan Department of Natural

Resources, 1971

Keeper listings for this light appear courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research |