|

Historical Information

Three miles in length and 1¼ miles

at its widest point, Manitou Island sits approximately 2¾ miles to the

east of Keweenaw Point at the northern end of the Keweenaw Peninsula.

Serving as the marker for an important turning point for both up and

down-bound vessels, as well as those making south toward Marquette and

Houghton, rocky shoals extended from the island's shores in all

directions, representing a significant threat to any captain passing too

close to the island during periods of limited visibility.

With

construction of the new lock at the Soo planned for completion in 1855,

a major boom in maritime commerce on Lake Superior was both expected and

eagerly anticipated, and a light on Manitou thus became of critical

importance to mariners. To this end the first station on Manitou Island

was built at the eastern end of the island in 1849 at a cost of $7,500.

While no known images of this station exist, we do know that it

consisted of a 60 foot tall rubble-stone tower outfitted with a Lewis

Lamp array at a focal plane of 71 feet. Angus M Smith received the

appointment as the stations first keeper, and moved into the simple

attached rubble stone dwelling on September 5, 1849, exhibiting the

light for the first time soon thereafter. With

construction of the new lock at the Soo planned for completion in 1855,

a major boom in maritime commerce on Lake Superior was both expected and

eagerly anticipated, and a light on Manitou thus became of critical

importance to mariners. To this end the first station on Manitou Island

was built at the eastern end of the island in 1849 at a cost of $7,500.

While no known images of this station exist, we do know that it

consisted of a 60 foot tall rubble-stone tower outfitted with a Lewis

Lamp array at a focal plane of 71 feet. Angus M Smith received the

appointment as the stations first keeper, and moved into the simple

attached rubble stone dwelling on September 5, 1849, exhibiting the

light for the first time soon thereafter.

On July 29 of the following year, Henry

B. Miller, the district Superintendent of Lights, accompanied the

contractor to inspect the new station, reporting that "Everything

here is in good order. The tower is, in my opinion, a good one, and is

all complete, with the exception of the spindle or lamp frame in the

tower, which is missing." The contractor pledged to install the

missing frame, and Miller signed-off on the project as complete and

satisfactory. While rapid deterioration of the structure over the

ensuing ten years indicates that Miller likely overlooked some serious

construction flaws, he was evidently aware of the isolated existence

keeper Smith was forced to endure, since in his report for that year

Miller recommended that the pay for a couple of keepers at less isolated

stations in the district be reduced, in order to allow a fifty dollar

increase in Smith's annual pay rate. On July 29 of the following year, Henry

B. Miller, the district Superintendent of Lights, accompanied the

contractor to inspect the new station, reporting that "Everything

here is in good order. The tower is, in my opinion, a good one, and is

all complete, with the exception of the spindle or lamp frame in the

tower, which is missing." The contractor pledged to install the

missing frame, and Miller signed-off on the project as complete and

satisfactory. While rapid deterioration of the structure over the

ensuing ten years indicates that Miller likely overlooked some serious

construction flaws, he was evidently aware of the isolated existence

keeper Smith was forced to endure, since in his report for that year

Miller recommended that the pay for a couple of keepers at less isolated

stations in the district be reduced, in order to allow a fifty dollar

increase in Smith's annual pay rate.

At the dawning of the decade, the

maritime community rose in anger at the dismally poor administration of

the nation's aids to navigation by the Fifth Auditor of the Treasury.

Congress reacted in 1852 by forming the Lighthouse Board, to which it

simultaneously transferred responsibility for the management of all

lighthouses. Made up of individuals with maritime and engineering

experience, one of the Board's first priorities was to undertake a

system-wide upgrading of illumination technology, switching over from

the universally adopted Lewis Lamp to the vastly superior French Fresnel

lenses. To this end, a work crew arrived at Manitou in 1856 to supervise

the replacement of the station's birdcage lantern with a modern

octagonal structure of cast iron, into which the District Lampist

carefully installed a flashing white Fourth Order Fresnel lens, thereby

increasing the station's visibility range to 14 miles in clear weather.

In 1855, Smith identified an additional

method through which he was able to increase his income, by having his

wife Lydia appointed as the station's assistant, a tactic repeated by

three following keepers! By 1859 the condition of the Manitou

Island station had deteriorated so far as to prompt Michigan Senator

Zachariah Chandler to raise the urgent need for repairs or replacement

in the Senate on February 10. In order to obtain a better understanding

of the issue, the matter was forwarded to the Department on Commerce

with instructions to investigate and to return with a recommended course

of action. Evidently the investigation proved positive, since the

necessary appropriation was made, and the Eleventh District Engineer

drew up plans for the construction of three virtually identical

structures at Manitou, Whitefish Point and Detour.

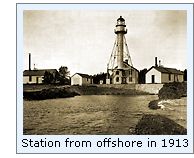

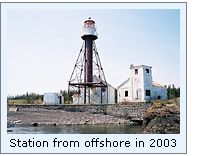

Contracts for the iron work and

building materials for the new station were awarded in 1861, and a work

crew dispatched to the island with the materials that summer. The tower

was built of prefabricated numbered cast iron sections which were

assembled in a manner similar to that of a giant erector set. The tower

featured a six-foot diameter cylindrical cast iron center cylinder of ¼

inch plates, with its interior wall lined with wood paneling to help

reduce condensation. Within this cylinder, a series of cast iron stairs

spiraled from the entry at the lower end to the lantern, which was also

fabricated of cast iron sections. The center cylinder and lantern were

supported by four tubular iron legs which were bolted to concrete

foundation pads. The four legs were in turn supported by horizontal

cross members with the entire assembly provided rigidity by way of

diagonal iron braces equipped with turnbuckles. Interestingly, the

central cylinder did not reach the ground, but was suspended

approximately 17 feet above ground level, with entrance gained from the

second floor of the two story wood frame dwelling through an elevated

covered passageway. Construction of the new station continued through

the arrival of winter in 1861, and then resumed with the opening of the

navigation. Contracts for the iron work and

building materials for the new station were awarded in 1861, and a work

crew dispatched to the island with the materials that summer. The tower

was built of prefabricated numbered cast iron sections which were

assembled in a manner similar to that of a giant erector set. The tower

featured a six-foot diameter cylindrical cast iron center cylinder of ¼

inch plates, with its interior wall lined with wood paneling to help

reduce condensation. Within this cylinder, a series of cast iron stairs

spiraled from the entry at the lower end to the lantern, which was also

fabricated of cast iron sections. The center cylinder and lantern were

supported by four tubular iron legs which were bolted to concrete

foundation pads. The four legs were in turn supported by horizontal

cross members with the entire assembly provided rigidity by way of

diagonal iron braces equipped with turnbuckles. Interestingly, the

central cylinder did not reach the ground, but was suspended

approximately 17 feet above ground level, with entrance gained from the

second floor of the two story wood frame dwelling through an elevated

covered passageway. Construction of the new station continued through

the arrival of winter in 1861, and then resumed with the opening of the

navigation.

On the station's completion in 1862,

the importance the Lighthouse Board placed on the station was witnessed

by the fact that the new lantern was outfitted with a large Third Order

Fresnel lens manufactured by Henry-Lepaute, an order of which only

nineteen would ever be displayed in all of the western Great Lakes

lights. The lens featured six bulls-eye flash panels, which when rotated

around the lamp would provide the station's designated characteristic of

a solid white light punctuated by intense white flashes once every

minute. With the station's completion, the old tower and dwelling were

in such poor condition that they were razed, being considered as unfit

for modification for alternate use. On the station's completion in 1862,

the importance the Lighthouse Board placed on the station was witnessed

by the fact that the new lantern was outfitted with a large Third Order

Fresnel lens manufactured by Henry-Lepaute, an order of which only

nineteen would ever be displayed in all of the western Great Lakes

lights. The lens featured six bulls-eye flash panels, which when rotated

around the lamp would provide the station's designated characteristic of

a solid white light punctuated by intense white flashes once every

minute. With the station's completion, the old tower and dwelling were

in such poor condition that they were razed, being considered as unfit

for modification for alternate use.

With the exception of the arrival of a

work crew to repair a crack in the iron band at the base of the main

tower cylinder and to repaint the entire station two years previous,

life on Manitou in 1870 was largely one of quiet isolation for Keeper

Charles Corgan and his brother Henry, who was serving as his assistant,

and it is quite likely that they were oblivious to plans being discussed

in Detroit and Washington that would forever change the sanctity of

their remote island station For it was in 1870 that the Lighthouse Board

recommended to Congress that funds be appropriated for the establishment

of a fog signal on the island to help guide mariners making the turn in

the pea soup fogs which frequently blanketed the area. Congress

responded quickly, appropriating $5,000 for the fog signal's

construction on March 3, 1871. With the exception of the arrival of a

work crew to repair a crack in the iron band at the base of the main

tower cylinder and to repaint the entire station two years previous,

life on Manitou in 1870 was largely one of quiet isolation for Keeper

Charles Corgan and his brother Henry, who was serving as his assistant,

and it is quite likely that they were oblivious to plans being discussed

in Detroit and Washington that would forever change the sanctity of

their remote island station For it was in 1870 that the Lighthouse Board

recommended to Congress that funds be appropriated for the establishment

of a fog signal on the island to help guide mariners making the turn in

the pea soup fogs which frequently blanketed the area. Congress

responded quickly, appropriating $5,000 for the fog signal's

construction on March 3, 1871.

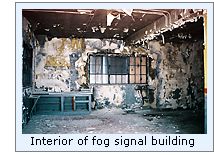

A pair of wood frame fog signal buildings

were erected on each side of the tower in 1875, with their interior walls lined with sheet iron for fire

protection, and on completion, each building was outfitted with its own steam

engine supplying steam to a 10-inch locomotive whistles. A pair of wood frame fog signal buildings

were erected on each side of the tower in 1875, with their interior walls lined with sheet iron for fire

protection, and on completion, each building was outfitted with its own steam

engine supplying steam to a 10-inch locomotive whistles.

According to Lighthouse Board policy,

station log books were supposed to contain concise single-line entries

reporting the weather conditions and notable happenings at the station,

with "no personal opinions or remarks on family affairs or ordinary

household work." However, James Corgan, who served as Keeper of the

Manitou Light from October 22, 1873 through July 29, 1875 was a strong-willed

individual, who took great pride in his abilities and intelligence. Not

one to suffer bureaucratic nonsense well, Corgan was surprisingly

forthright in his log entries. On August 5, 1875, Corgan visited L'Anse, where he

learned of the Board's impending decision to remove him from his

position. Click here to view

excerpts of the Manitou station log book.

Over the ensuing years, the Manitou fog signals proved to be one of the

most active in the district, and by the late 1880's it was determined

that the apparatus in both buildings had outlived their useful lives. The lighthouse tender

AMARANTH arrived at the station with a work party and the necessary

supplies for construction in late May of 1899. The north fog signal building

was extended 12 feet to an overall length of 42 feet in order to make

room for both sets of apparatus, and a new concrete

floor poured throughout. After removal of the worn out apparatus, the

new machinery was installed and tested. With the construction of a 12

foot by 17 foot coal bin, construction was completed on July 3, and the

AMARANTH returned to remove the work party to transport them to their

next work assignment.

It would appear that there were some

significant personnel problems encountered at the station in 1881, since

Keeper Henry Guilbault and his 2nd assistant Richard Rickard were both

simultaneously removed from their positions on October 22, 1881, leaving

Guibault's brother Norman, the station's 1st Assistant temporarily in

charge. Reuben Hart, who had been serving at Huron Island for the past

two years was promoted as Acting Keeper of the Manitou Light. On Hart's

arrival at Manitou on October 26, Guilbault was simultaneously

transferred to Huron Island to fill the opening left by Hart's

promotion. Hart appears to have manned the station single-handedly

through the end of the 1881 navigation season. It would appear that there were some

significant personnel problems encountered at the station in 1881, since

Keeper Henry Guilbault and his 2nd assistant Richard Rickard were both

simultaneously removed from their positions on October 22, 1881, leaving

Guibault's brother Norman, the station's 1st Assistant temporarily in

charge. Reuben Hart, who had been serving at Huron Island for the past

two years was promoted as Acting Keeper of the Manitou Light. On Hart's

arrival at Manitou on October 26, Guilbault was simultaneously

transferred to Huron Island to fill the opening left by Hart's

promotion. Hart appears to have manned the station single-handedly

through the end of the 1881 navigation season.

On March 29, 1882, Henry Ferguson and

John Gustafson arrived on Manitou, freshly hired to fill the positions

of 1st and 2nd Assistant Keepers, respectively. Evidently neither

Ferguson nor Gustafson were cut from the right cloth for lighthouse

service, and hiring the two men proved to be a mortal error for Hart. A

scant few months later, the two men would stand by as they watched

Hart's boat overturn a few feet off the island with neither of them

lifting a finger to render assistance.

In a strange twist of fate, James

Corgan who had been re-hired into lighthouse service as keeper of the

Gull Rock Light was the first outsider to come to Manitou after the

incident and helped search for the body. Instructed to temporarily

assume responsibility for Manitou until a new Keeper could be assigned,

Corgan recounted the story in detail in the Manitou log book. Click

here to read Corgan's full account directly from the Manitou

log.

As part of a system-wide upgrade, a

brick oil storage house was built in 1895, and the fog signal apparatus

was thoroughly overhauled. Two years later, a sixty foot long dock was

constructed of huge timber cribs filled with stone. Amazingly, these

massive cribs were pulverized during a violent gale in October 1898, and

a work crew was dispatched to the island to undertake temporary repairs

late that season. While on site, the crew also began blasting the rocky

shore to prepare for the construction of a boat house and boat ways.

While the tender AMARANTH delivered a hoisting engine for the station

and materials for the construction of more permanent cribs and a derrick

in 1900, it was not until 1901, that a work crew was placed on the

island to complete construction of the boathouse, boat ways, dock and

derrick, and to repaint the tower, changing its color from brown to

white. As part of a system-wide upgrade, a

brick oil storage house was built in 1895, and the fog signal apparatus

was thoroughly overhauled. Two years later, a sixty foot long dock was

constructed of huge timber cribs filled with stone. Amazingly, these

massive cribs were pulverized during a violent gale in October 1898, and

a work crew was dispatched to the island to undertake temporary repairs

late that season. While on site, the crew also began blasting the rocky

shore to prepare for the construction of a boat house and boat ways.

While the tender AMARANTH delivered a hoisting engine for the station

and materials for the construction of more permanent cribs and a derrick

in 1900, it was not until 1901, that a work crew was placed on the

island to complete construction of the boathouse, boat ways, dock and

derrick, and to repaint the tower, changing its color from brown to

white.

1907 saw the installation of 80

concrete sidewalk slabs which had been pre-cast at the Detroit depot and

the installation of a steel water supply tank for the fog signals. This

was also a memorable year for the Manitou Keepers, as they hauled and

shoveled 40 tons of coal during the season to keep the fog signals

screaming for a station-high 627 hours.

In order to increase the range of

visibility of the light, the lamp was changed from kerosene to

incandescent oil vapor on June 30, 1913, with an impressive increase in

output from 15,000 to 220,000 candlepower. At this time, the

characteristic of the light was also changed to flashing white every 10

seconds

With the growing maritime adoption of

radio technology, a radio beacon was installed at the station on October

23, 1925. Emitting a repeated characteristic of sixty-second blasts of

three Morse Code dashes followed by a ninety second silence, the beacon

was activated during periods of thick weather and for a half hour each

morning and afternoon for testing purposes. 1928 saw the electrification

of the Light and dwelling through the installation of diesel powered

generator and battery system. Under the Works Project Administration,

the fog signal was completely rebuilt in 1930, and the steam whistles

replaced by a pair of compressor-powered Type F

diaphones. Also around this time, an underwater telephone line

was laid from Keweenaw Point to the station, truly bringing the

twentieth century to the island. With the growing maritime adoption of

radio technology, a radio beacon was installed at the station on October

23, 1925. Emitting a repeated characteristic of sixty-second blasts of

three Morse Code dashes followed by a ninety second silence, the beacon

was activated during periods of thick weather and for a half hour each

morning and afternoon for testing purposes. 1928 saw the electrification

of the Light and dwelling through the installation of diesel powered

generator and battery system. Under the Works Project Administration,

the fog signal was completely rebuilt in 1930, and the steam whistles

replaced by a pair of compressor-powered Type F

diaphones. Also around this time, an underwater telephone line

was laid from Keweenaw Point to the station, truly bringing the

twentieth century to the island.

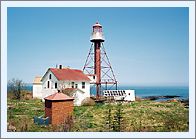

Today, Manitou station still serves as

a guide to mariners, it's light currently provided by a 12-volt solar

powered 190 mm acrylic, displayed from the same position in the lantern

from which the mighty Third Order Fresnel once stood. As of this date,

we have been unable to identify the disposition of the Fresnel, and

would appreciate hearing from anyone who might know of its whereabouts

that at least in the words on this page we might reunite it with its

station.

Keepers of

this Light

Click here to

see a complete listing of all Manitou Island Light keepers compiled by

Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Seeing this Light

We have yet to visit this light, but

will update with our observations as soon as we arrange to make landfall

on the island.

Finding this

Light

Keweenaw Excursions offers various lighthouse cruises on board the

KEWEENAW STAR out of Houghton, Michigan. A number of these tours include

close passes by the Gull Rock Light. For more information on any of

their tours visit their website,

or telephone Keweenaw Excursions at (906) 482-0884.

Reference Sources

Annual report of the Fifth Auditor of the Treasury, 1850

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Board, various, 1853 through

1909.

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Service, various, 1910 through

1939.

Annual reports of the Lake Carrier's Association, 1939 through

1950

Great Lakes Light Lists, 1861. 1872. 1901, 1928, 1939.

US Lake Survey Great Lakes Pilot, 1958.

Keeper listings for Michigan Island Light appears

courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|