|

Historical Information

With the establishment of the Duluth South Breakwater Light in 1874 the

task of locating Duluth harbor was much simplified. However, with only

300 feet between the north pier and the south breakwater, identifying

the correct entry course that would place a vessel smack dab between

them was somewhat risky.

To rectify this situation, in 1880 the

Lighthouse Board recommended that the sum of $2,000 be made available

for the construction of a light on the inner end of the south

breakwater. By constructing this new tower with a focal plane higher

than that of the existing breakwater light, the two lights would combine

to serve as a range, and by maintaining a line in which these two lights

were constantly oriented one above the other, a direct course could be

followed to the opening between the two piers. To rectify this situation, in 1880 the

Lighthouse Board recommended that the sum of $2,000 be made available

for the construction of a light on the inner end of the south

breakwater. By constructing this new tower with a focal plane higher

than that of the existing breakwater light, the two lights would combine

to serve as a range, and by maintaining a line in which these two lights

were constantly oriented one above the other, a direct course could be

followed to the opening between the two piers.

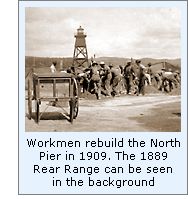

After receiving a Congressional

appropriation on March 2,1889, construction began on a timber pyramid

tower surmounted by a frame watch room. Topped with an octagonal cast

iron lantern, and equipped with a flashing red Fourth Order Fresnel lens

emitting a single flash every six seconds, the "sweet pot" of

which was situated at a focal plane above that of the South Breakwater

Light. After receiving a Congressional

appropriation on March 2,1889, construction began on a timber pyramid

tower surmounted by a frame watch room. Topped with an octagonal cast

iron lantern, and equipped with a flashing red Fourth Order Fresnel lens

emitting a single flash every six seconds, the "sweet pot" of

which was situated at a focal plane above that of the South Breakwater

Light.

Work on the new structure continued

through the summer, and the new rear range light was exhibited for the

first time on the night of September 1. Sixteen days later, on September

17, the steamer India was encountering some problems making her way

between the piers, and smashed into the breakwater at the foot of the

new light, damaging the light's foundation. Repairs were made quickly at

the expense of the vessel's owners.

By 1897, Duluth had grown to become one

of the Great Lake's preeminent ports, and the town was expanding rapidly

to envelope the hills surrounding the natural harbor. With the resulting

proliferation of city lights, mariners voiced concern that the lights of

the range were becoming increasingly difficult to differentiate from

those of the city, and the Lighthouse Board contemplated increasing

their visibility by substituting lenses of a higher order, or changing

their characteristics to something more readily identifiable. By 1897, Duluth had grown to become one

of the Great Lake's preeminent ports, and the town was expanding rapidly

to envelope the hills surrounding the natural harbor. With the resulting

proliferation of city lights, mariners voiced concern that the lights of

the range were becoming increasingly difficult to differentiate from

those of the city, and the Lighthouse Board contemplated increasing

their visibility by substituting lenses of a higher order, or changing

their characteristics to something more readily identifiable.

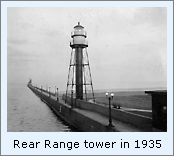

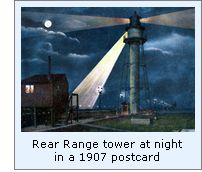

In the summer of 1901, the iron work

for the permanent tower was delivered, and work began with the

installation of two large concrete blocks within the breakwater to serve

as its foundation. The structure itself consisted of an eight foot

diameter iron cylinder containing a spiral cast iron stairway. Atop this

cylinder, a galvanized iron gallery with circular watch room was

supported by four tubular legs radial to the central cylinder, and

diagonally braced with struts and tension rods. Capped with an octagonal

cast iron lantern, the structure stood seventy feet from the base of the

cylinder to the top of the ventilator ball, and provided the Fourth

Order Fresnel lens with a focal plane of 68 feet. To provide a measure

of visual contrast and improve the station's function as a day mark, the

lantern and watch room were painted black, with all remaining components

painted a bright white. In the summer of 1901, the iron work

for the permanent tower was delivered, and work began with the

installation of two large concrete blocks within the breakwater to serve

as its foundation. The structure itself consisted of an eight foot

diameter iron cylinder containing a spiral cast iron stairway. Atop this

cylinder, a galvanized iron gallery with circular watch room was

supported by four tubular legs radial to the central cylinder, and

diagonally braced with struts and tension rods. Capped with an octagonal

cast iron lantern, the structure stood seventy feet from the base of the

cylinder to the top of the ventilator ball, and provided the Fourth

Order Fresnel lens with a focal plane of 68 feet. To provide a measure

of visual contrast and improve the station's function as a day mark, the

lantern and watch room were painted black, with all remaining components

painted a bright white.

With two lights and a frequently active

fog signal, a head keeper and two assistants were assigned to the Duluth

Light station. However the only dwelling available to the crew was the

small frame house built for the keeper in 1874. As a result, the two

assistant keepers were forced to rent their own dwellings in town, at a

cost of $10 and $15 per month, a considerable cost to those earning the

less than princely sums that the position afforded. Thus, the Lighthouse

Board requested an appropriation of $10,000 for the purchase of land and

the construction of a duplex dwelling in the area of the rear range for

the assistants and their families in its 1903 annual report. With two lights and a frequently active

fog signal, a head keeper and two assistants were assigned to the Duluth

Light station. However the only dwelling available to the crew was the

small frame house built for the keeper in 1874. As a result, the two

assistant keepers were forced to rent their own dwellings in town, at a

cost of $10 and $15 per month, a considerable cost to those earning the

less than princely sums that the position afforded. Thus, the Lighthouse

Board requested an appropriation of $10,000 for the purchase of land and

the construction of a duplex dwelling in the area of the rear range for

the assistants and their families in its 1903 annual report.

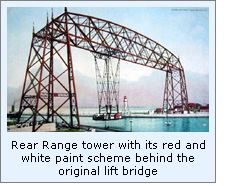

Congress ignored the request, however

the Board did not give up easily, reiterating its request every year

until an appropriation of $2,000 for the purchase of land was finally

made on March 4, 1907, with an additional appropriation for the actual

construction of the dwelling on May 27 of the following year. While an

empty lot directly across Lake Avenue from the head keepers' dwelling

was selected, there was some wrangling required in order to obtain

Government title to the property, and the structures were thus not

completed and occupied until February, 1913. As completed, the building

consisted of a two story brick duplex structure with a roof of asbestos

shingles. Replete with all conveniences of the day, the first floor of

each apartment consisted of an entry vestibule, living room, dining

room, kitchenette and pantry. With two bedrooms and a bath on the second

floors, the entire structure was heated by a hot-water heating system

located in the cellar. Both dwellings are still standing, and can be

seen flanking Lake Avenue immediately to the east of the aerial lift

bridge. Congress ignored the request, however

the Board did not give up easily, reiterating its request every year

until an appropriation of $2,000 for the purchase of land was finally

made on March 4, 1907, with an additional appropriation for the actual

construction of the dwelling on May 27 of the following year. While an

empty lot directly across Lake Avenue from the head keepers' dwelling

was selected, there was some wrangling required in order to obtain

Government title to the property, and the structures were thus not

completed and occupied until February, 1913. As completed, the building

consisted of a two story brick duplex structure with a roof of asbestos

shingles. Replete with all conveniences of the day, the first floor of

each apartment consisted of an entry vestibule, living room, dining

room, kitchenette and pantry. With two bedrooms and a bath on the second

floors, the entire structure was heated by a hot-water heating system

located in the cellar. Both dwellings are still standing, and can be

seen flanking Lake Avenue immediately to the east of the aerial lift

bridge.

In 1995, an inspection of the Fourth

Order Fresnel lens showed that it was in dire need of repairs, and thus

the Coast Guard decided to replace the old lens with a modern acrylic

optic, and donated the Fresnel to the Maritime Museum. The lens was

subsequently restored and the pedestal and clockwork rotating mechanism

were removed from the tower to be reunited with the lens. Today, both

may be seen on display in the Knowlton Gallery within the Museum. Today,

the colors of the rear range light have been reversed, with the central

cylinder and support legs now painted black, and the watch room white.

Keepers of

this Light

Click

here to see a complete listing of all keepers of the Duluth

Lights compiled by Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Seeing these

Lights

Duluth turned-out to be

the big surprise of this yearís trip. We expected a dismal & dirty

port city, with nothing to keep our attention beyond the three lights on

the harbor pier. Were we in for a real surprise! The entire downtown and

waterfront area has been through a major renovation, and there was a ton

of things to do.

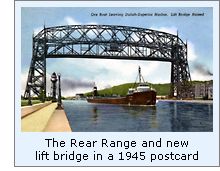

All three lighthouses are on piers on either side of a canal that was

cut through a huge sand spit which protects the harbor on which the city

is built. The road across the canal is accommodated by the Duluth lift

bridge, which was built in 1902, and being one of Superiorís busiest

ports, both Lakers and Salties are coming and going throughout the day. All three lighthouses are on piers on either side of a canal that was

cut through a huge sand spit which protects the harbor on which the city

is built. The road across the canal is accommodated by the Duluth lift

bridge, which was built in 1902, and being one of Superiorís busiest

ports, both Lakers and Salties are coming and going throughout the day.

While on the North

pier, we visited the Canal Park Maritime Museum, which is run by the

Army Corps of Engineers, and located tight against the lift bridge. We

found this to be a fascinating museum, and is the current location of

the Fourth Order Fresnel lens formerly located in the rear range

lantern. Museum hours vary

by season. Summer hours generally are 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. daily; Spring

and Fall hours are 10 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. daily, and Winter hours are 10

a.m. to 4 p.m. Friday through Sunday. For more information, call the

museum at (218) 727-2497

Finding these Lights

Hwy 61 slices through Duluth parallel to the lakeshore. All three Duluth

lighthouses are located on piers protecting the canal through a long

sand bar which protects the Port of Duluth, and are all located in

an area known as Canal Park, which is well signed. From Hwy 61, take

Canal Park Drive into Canal Park drive, and find a place to park before

crossing the famous lift bridge. The lighthouses are a short walk from

the bridge. The North Breakwater Light is located at the end of the pier

on the North side of the canal, and both South lights are (naturally)

located on the South side of the canal, which can be reached by walking

across the lift bridge. If the horn sounds followed by a message to

"clear the bridge" is heard, be sure to get off the bridge

quickly, as they do not give.

Reference

Sources

Annual reports of the

Lighthouse Board, various, 1880-1909

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Establishment, various,1910-1939

Annual report of the Lake Carriers Association, 1908

Inventory of Historic Light Stations,

National Parks Service,

1994.

The Northern Lights, Charles K. Hyde, 19995

Observation during visit to Duluth Harbor on

09/06/1999

Keeper listings for this light appear courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|