|

Historical

Information

Located approximately 20 miles east of Mackinac Point and 2.6

miles northwest of Waugoshance Island, the

shallows around White Shoal had long presented a hazard for vessels

entering the

Straits from the either the North Shore or the Manitou Passage.

Lying in an east/west orientation, and almost two miles long, the shoal

was so shallow that its west end broke the water's surface.

With the dramatic increase in vessel

traffic in the late 1880's, the Lighthouse Board specifically identified

White Shoal, Simmons Reef and Gray's Reef as three Straits-area

navigational hazards requiring immediate demarcation. While the

construction of permanent navigational aids was preferred, it was soon

evident that the anchoring of lightships over the hazards represented a

significantly more expeditious and far more cost effective solution.

Bids were submitted to a number of

shipbuilders, with the $60,000 contract for the construction of three

sister vessels awarded to the Blythe Craig Shipbuilding Co of Toledo

Ohio. Wood framed and planked, the three identical 130 gross tonnage

vessels were built with a length of almost 103 feet, a 20' beam, and a

draft of 7' 5". Equipped with single-cylinder non-condensing steam

engines, they were the first U.S. light vessels to be outfitted with

self-propelling engines. Each vessel displayed a cluster of three

oil-burning lens lanterns hoisted on the masthead, and a six-inch steam

whistle and a hand operated bell for use during periods of decreased

visibility.

Work on the vessels was completed on

September 15, 1891, whereupon they were turned over to the Lighthouse

Establishment, and officially designated as LV55, LV56 and LV57. Upon

receipt of the vessels, the Lighthouse Establishment conducted a series

of sea trials through October 6. After a number of minor modifications,

the three vessels departed the Lighthouse Depot in Detroit on October

19, reaching Port Huron that same evening, where they were met by the

lighthouse tender Dahlia, who began towing them north along the western

shore of Lake Huron. LV56 was finally delivered on station at White

Shoal on October 24, and was secured to the five-ton sinker and 15

fathoms of 2-inch chain, which had previously been placed on the shoal

in preparation for the vessel's arrival. Work on the vessels was completed on

September 15, 1891, whereupon they were turned over to the Lighthouse

Establishment, and officially designated as LV55, LV56 and LV57. Upon

receipt of the vessels, the Lighthouse Establishment conducted a series

of sea trials through October 6. After a number of minor modifications,

the three vessels departed the Lighthouse Depot in Detroit on October

19, reaching Port Huron that same evening, where they were met by the

lighthouse tender Dahlia, who began towing them north along the western

shore of Lake Huron. LV56 was finally delivered on station at White

Shoal on October 24, and was secured to the five-ton sinker and 15

fathoms of 2-inch chain, which had previously been placed on the shoal

in preparation for the vessel's arrival.

Life onboard the vessel was evidently

not too agreeable to the first crew of the LV56, since without orders

they abandoned their station during a storm on November 17, and put into

their winter quarters in Cheboygan. The entire crew was immediately

discharged for dereliction of duty, and a replacement crew quickly

selected. The tender Dahlia again towed LV56 back to her station on

November 22, where she remained until close of the shipping season, when

she received orders to return to her Cheboygan winter quarters. With the

exception of her annual winter lay-ups from late December through

ice-out in April or May, LV56 continued her faithful service at White

Shoal for the following nineteen years.

Largely as a result of repeated

difficulties getting the lightship on and off station at the beginning

and end of each navigation season, in 1906 the Lighthouse Board

petitioned the U.S. Congress for the funds to construct a permanent

light station on the shoal. Congress responded favorably on March 4,

1907 with an appropriation of $250,000 for the project, and with Major

William V. Judson U.S.A.C.E, and lighthouse engineer for the Michigan

District in charge of both the design and construction, work began at

White Shoal the following year.

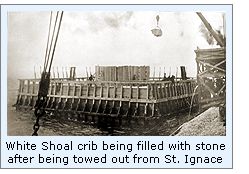

Spring of 1908 saw work begin on the

White Shoal light on two separate fronts. While a crew at the site leveled a one hundred and two-foot square area on the shoal through the

addition and careful placement of loads of stone, a second crew worked

on building a timber crib on shore at St. Ignace. Seventy-two feet

square and eighteen and a half feet high, the huge crib contained

400,000 square feet of lumber, and on completion was slowly towed

out to the shoal and centered over the leveled lake bottom. Once in

location, the crib was filled with 4,000 tons of stone until it sank to a point at

which its' uppermost surface was level and two feet below the water's

surface. Spring of 1908 saw work begin on the

White Shoal light on two separate fronts. While a crew at the site leveled a one hundred and two-foot square area on the shoal through the

addition and careful placement of loads of stone, a second crew worked

on building a timber crib on shore at St. Ignace. Seventy-two feet

square and eighteen and a half feet high, the huge crib contained

400,000 square feet of lumber, and on completion was slowly towed

out to the shoal and centered over the leveled lake bottom. Once in

location, the crib was filled with 4,000 tons of stone until it sank to a point at

which its' uppermost surface was level and two feet below the water's

surface.

On top of this crib, a seventy-foot

square stone block base was constructed to a total height of four

feet, with the remainder of the pier being of poured concrete atop the

block base. With the base complete, an acetylene-powered lens lantern

was installed atop a temporary steel skeletal tower on December 5th, and

with the onset of winter storms, work at the

shoal ended for the season. On top of this crib, a seventy-foot

square stone block base was constructed to a total height of four

feet, with the remainder of the pier being of poured concrete atop the

block base. With the base complete, an acetylene-powered lens lantern

was installed atop a temporary steel skeletal tower on December 5th, and

with the onset of winter storms, work at the

shoal ended for the season.

Work crews returned the following year

to find the crib and pier in excellent condition, and the work effort

turned toward construction of the tower itself. Work on this second year

started with the erection of a skeletal steel framework that had been

prefabricated offsite over the winter, and disassembled for shipment to

the shoal. This framework was then lined with bricks and covered with a

skin of terra cotta blocks. With an outside diameter of forty-two feet

at the base, the tower tapered gracefully to a diameter of twenty feet

at its' uppermost below the gallery.

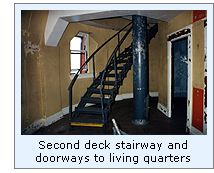

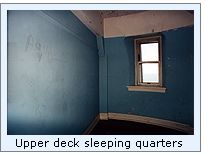

As work on the tower continued,

the nine decks took shape within the tower. The first deck mechanical

room housed the oil engine powered fog signal, heating plant, and storage for the

station's powerboat. The second deck housed a tool room, bathroom and food

storage area. A kitchen, living room and one bedroom made up the third

deck, with two more bedrooms and a toilet located on the fourth. A

living area and another bedroom were found on the fifth deck, and the

sixth and seventh contained a single open room on each. The service room

made up the eighth level, and the watchroom topped the living quarters

on the ninth. As work on the tower continued,

the nine decks took shape within the tower. The first deck mechanical

room housed the oil engine powered fog signal, heating plant, and storage for the

station's powerboat. The second deck housed a tool room, bathroom and food

storage area. A kitchen, living room and one bedroom made up the third

deck, with two more bedrooms and a toilet located on the fourth. A

living area and another bedroom were found on the fifth deck, and the

sixth and seventh contained a single open room on each. The service room

made up the eighth level, and the watchroom topped the living quarters

on the ninth.

Work at the station continued through

the end of the shipping season in 1909, when once again the station was

abandoned until work could resume with the receding ice in the spring of

1910.

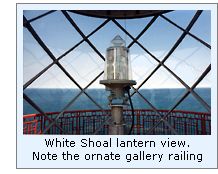

Work

crews returned to the station on the opening of the 1910 navigation

season, and the the tower was

capped with a circular watch room and lantern room, both of twelve and a

half feet in diameter. The aluminum lantern featured helical astragals,

which the Board had recently begun incorporating in new construction,

since it was believed that they offered less light interference than the

vertical astragals that had been prevalently used for the past sixty

years. As construction of the tower wound to completion, the entire

structure from the crib deck to lantern ventilator was given a coat of

bright white paint, designed to improves the structure's visibility

during daylight hours.

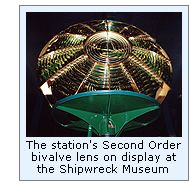

After

the District Lampist arrived at the site and installed

the massive Second Order Fresnel lens

the new light was exhibited for the first time on the night of September

1, 1910. Manufactured by Barbier, Benard

& Turenne of Paris, the lens was built in a two-sided design known

as a bi-valve configuration, with each side featuring 7 refracting and

15 reflecting prisms. In order to allow the heavy lens assembly to rotate with the

minimum amount of friction, the entire structure was floated in a

trough of mercury, and rotated by a clockwork mechanism, which was

powered by hanging weights. Located at a focal plane of 125 feet, the

lens rotated once every 32 seconds. Its 55mm double tank incandescent

oil vapor lamp was thus magnified to 1,200,000 candlepower, making the

light visible for a remarkable distance of 28 miles in clear weather

conditions. After

the District Lampist arrived at the site and installed

the massive Second Order Fresnel lens

the new light was exhibited for the first time on the night of September

1, 1910. Manufactured by Barbier, Benard

& Turenne of Paris, the lens was built in a two-sided design known

as a bi-valve configuration, with each side featuring 7 refracting and

15 reflecting prisms. In order to allow the heavy lens assembly to rotate with the

minimum amount of friction, the entire structure was floated in a

trough of mercury, and rotated by a clockwork mechanism, which was

powered by hanging weights. Located at a focal plane of 125 feet, the

lens rotated once every 32 seconds. Its 55mm double tank incandescent

oil vapor lamp was thus magnified to 1,200,000 candlepower, making the

light visible for a remarkable distance of 28 miles in clear weather

conditions.

After activation of the new light station, LV56 was no longer needed at White Shoal, and the vessel was reassigned

to duty at North Manitou Shoal, where she stayed through every shipping

season until 1927 when she was once again reassigned to Gray's Reef. She

was retired from service in 1928, and was sold into private ownership on

December 20 of that same year.

A

submarine bell located in 70 feet of water approximately 3/4 of a mile

from the crib was installed in 1911, and placed into operation on

September 20. Powered by a submarine electrical cable from the station,

the sound transmission property of the water allowed the bell to be

heard through the hulls of approaching vessels long before the fog

signals could be heard in thick weather. A

submarine bell located in 70 feet of water approximately 3/4 of a mile

from the crib was installed in 1911, and placed into operation on

September 20. Powered by a submarine electrical cable from the station,

the sound transmission property of the water allowed the bell to be

heard through the hulls of approaching vessels long before the fog

signals could be heard in thick weather.

1913

saw the installation of a pair of compressed air operated deck cranes for unloading supplies, and for raising and

lowering the keepers boat which was used for both bringing supplies

and taking shore leave. To further improve the station's efficacy during

thick weather, the six-inch whistles were removed and replaced with

10-inch whistles on April 22, 1914. Proving to be less successful as

originally intended, the submarine bell was permanently discontinued at

the end of the 1914 season of navigation. 1913

saw the installation of a pair of compressed air operated deck cranes for unloading supplies, and for raising and

lowering the keepers boat which was used for both bringing supplies

and taking shore leave. To further improve the station's efficacy during

thick weather, the six-inch whistles were removed and replaced with

10-inch whistles on April 22, 1914. Proving to be less successful as

originally intended, the submarine bell was permanently discontinued at

the end of the 1914 season of navigation.

In 1930, twin

diesel engine-powered generators were installed in the mechanical

room, providing electrical power to both the living quarters and the

light, which a resulting increase in output to 3,000,000 candlepower.

With its multiple windows an all sides

of the tower, duty at White shoal was surprisingly comfortable during the summer,

since there was always good cross ventilation. In the Spring and early

winter, the oil engines furnished steam heat

to radiators located on all floors, keeping the temperature comfortable

year-round. After the Coast Guard's assumption of responsibility for the nation's

aids to navigation in 1939, four-man crews were assigned at the station.

Working a 14-days on and 7-days schedule, three seamen were always on

board while the fourth man was on Liberty.

The station was automated in 1976 with

the installation of a 12-volt DC solar-powered 190mm Tidelands Signal acrylic lens. The Second

Order Fresnel was dismantled in 1983, and relocated to the Shipwreck

Museum at Whitefish Point Light Station where it is

proudly displayed to this

day. The station was automated in 1976 with

the installation of a 12-volt DC solar-powered 190mm Tidelands Signal acrylic lens. The Second

Order Fresnel was dismantled in 1983, and relocated to the Shipwreck

Museum at Whitefish Point Light Station where it is

proudly displayed to this

day.

A Coast Guard crew arrived at the

station in 1990, and the tower was repainted with its' current

"candy cane" red and white spiral daymark. With the

application of this daymark, White Shoal stands as the only tower on all

of the Great Lakes to feature such a diagonally banded paint scheme. A Coast Guard crew arrived at the

station in 1990, and the tower was repainted with its' current

"candy cane" red and white spiral daymark. With the

application of this daymark, White Shoal stands as the only tower on all

of the Great Lakes to feature such a diagonally banded paint scheme.

As of this writing, we have been unable

to determine the fate of LV56 after she was sold into private ownership

in 1928. If any of our visitors have definitive information as to the

history of this vessel after that date, we would appreciate hearing from

you.

Keepers of this

Light

Click Here

to see a complete listing of

all White Shoal Light keepers compiled by Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes

Lighthouse Research.

Seeing

this Light

Sheplers

Ferry Service out of Mackinaw City offers a number of lighthouse cruises

during the summer season. Their "Westward Tour" includes

passes by White Shoal, Grays Reef, Waugoshance and St. Helena Island.

For schedules and rates for this tour, visit their website at: www.sheplerswww.com

or contact them at:

PO Box 250

Mackinaw City, MI 49701

Phone (800) 828-6157

Reference

Sources

Inventory

of Historic Light Stations, National Parks Service, 1994

USCG Historians office, Photographic

archives.

Annual Reports of the Lighthouse Board, various, 1867 - 1909

Annual Reports of the Lighthouse Service, 1910 - 1913

Annual Reports of the Lake Carriers Association, 1908 - 1938

Email correspondence with Timothy Larson and Art Miller who both

served at the station with USCG.

Lightships and Lightship Stations of the United States Government,

Willard Flint, 1989

Great Lakes Coast Pilot, NOAA, 2000

Keeper listings for this light appear

courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|