|

Historical

Information

Stretching two and a half miles in length and a scant half-mile

off the harbor entrance, Racine Reef lurked less than ten feet below the

surface at its shallowest point, and had claimed many a vessel making

its way in and out of Racine harbor over the years. While the Root River

Light had been guiding mariners into the mouth of the Root River for

almost thirty years, it was not until 1868 that the Lighthouse Board

undertook an evaluation of marking the hazard of the reef itself.

Simultaneous to this evaluation, the

Board was considering the construction of a major 108-foot tall coast

light at Wind Point, some three and a half miles to the north. With the

cost of constructing a manned station on the reef itself identified as

being prohibitive, the Board determined that the combination of an

auxiliary Sixth Order Fresnel

lens atop this new tower with its beam directed

towards the reef and a buoy upon the reef itself would provide the most

cost-effective solution to marking the hazard. To this end a buoy was

placed on Racine Reef in 1869 and the Board followed-up with a request

for $40,000 for the construction of the light at Wind Point in its

annual report for fiscal 1870. Congress was slow to act upon the

request, and the light at Wind Point was not completed and exhibited

until November 15, 1880. Simultaneous to this evaluation, the

Board was considering the construction of a major 108-foot tall coast

light at Wind Point, some three and a half miles to the north. With the

cost of constructing a manned station on the reef itself identified as

being prohibitive, the Board determined that the combination of an

auxiliary Sixth Order Fresnel

lens atop this new tower with its beam directed

towards the reef and a buoy upon the reef itself would provide the most

cost-effective solution to marking the hazard. To this end a buoy was

placed on Racine Reef in 1869 and the Board followed-up with a request

for $40,000 for the construction of the light at Wind Point in its

annual report for fiscal 1870. Congress was slow to act upon the

request, and the light at Wind Point was not completed and exhibited

until November 15, 1880.

Eventually realizing that the auxiliary

red Sixth Order lens was not sufficiently visible at sea to adequately

serve as an effective warning for Racine Reef, the lens was replaced by

a more powerful locomotive headlight with a parabolic reflector in 1897.

As the nineteenth century drew to a

close, the Lighthouse Board came to the realization that the Wind Point

solution was not serving as an adequate warning for the reef, and the

Board set upon the task of planning a more permanent aid to navigation

directly atop the reef itself. However, still deeming the cost of

constructing a manned station as being prohibitive, plans were instead

drawn-up for the construction of a concrete crib topped by a small tower

with a Pintsch gas powered light, to be serviced by the keepers of the

Harbor Lights by boat. As the nineteenth century drew to a

close, the Lighthouse Board came to the realization that the Wind Point

solution was not serving as an adequate warning for the reef, and the

Board set upon the task of planning a more permanent aid to navigation

directly atop the reef itself. However, still deeming the cost of

constructing a manned station as being prohibitive, plans were instead

drawn-up for the construction of a concrete crib topped by a small tower

with a Pintsch gas powered light, to be serviced by the keepers of the

Harbor Lights by boat.

To this end, a wooden crib, forty feet

square and nine feet high was constructed onshore in the harbor and

towed out to the reef in August 1898, and sunk on the bottom by filling

with bags of concrete. The crib was then faced with paving brick, and

the structure topped with a level cap of concrete. Between October and

November, sixty cords of riprap were then distributed around the

structure to break up wave action and help prevent erosion, and with the

arrival of ice and winter storms the work was halted until the opening

of navigation the following year. Over that winter, contracts were

awarded for the construction of a tower and the Pintsch gas illuminating

apparatus, and delivered at the Milwaukee depot. Work on the reef

resumed the following spring, and continued through the summer, and

after an initial charging of the storage tank with gas the new light was

exhibited for the first time on the night of August 31, 1899.

On the opening of the season of

navigation the following year, it was found that the action of the

winter ice had again caused significant damage to the exterior surfaces

of the crib, and as a temporary measure, two cords of old building stone

left over from the demolition of the upper section of the tower at

Rawley Point in 1894 were shipped to the reef and added to the riprap

protection installed the previous year. After the gas tanks ran empty on

a couple of occasions causing the light to be extinguished, one of the

gas storage tanks was replaced with a larger capacity unit, and in what

would become a virtually annual ritual on the reef, another eighty-one

cords of riprap were deposited around the crib by the end of 1900. On the opening of the season of

navigation the following year, it was found that the action of the

winter ice had again caused significant damage to the exterior surfaces

of the crib, and as a temporary measure, two cords of old building stone

left over from the demolition of the upper section of the tower at

Rawley Point in 1894 were shipped to the reef and added to the riprap

protection installed the previous year. After the gas tanks ran empty on

a couple of occasions causing the light to be extinguished, one of the

gas storage tanks was replaced with a larger capacity unit, and in what

would become a virtually annual ritual on the reef, another eighty-one

cords of riprap were deposited around the crib by the end of 1900.

It soon became plain that the new light

was ill-suited for its purpose on a number of levels. Even under the

best conditions, the shallow and rocky water around the crib made it

extremely difficult for the lighthouse tender Dahlia to get any closer

than 900 feet from the crib, making filling of the gas storage tanks

extremely difficult, and with the shipping channels between Milwaukee

and Chicago frequently kept open all year, this job became virtually

impossible with the arrival of winter ice. Finally, the Pintsch gas

illumination itself proved to be extremely bothersome, and while the

contractors who installed the light were forced to return to make

adjustments to the light on a number of occasions, the quality of the light was never

considered satisfactory. In a last-ditch effort to increase the

visibility of the failing light, it was increased in height by the

addition of a twenty-foot tall skeletal iron structure atop the existing

tower in 1901 - along with the inevitable addition of twenty-five yards

of additional riprap around the base of the crib. It soon became plain that the new light

was ill-suited for its purpose on a number of levels. Even under the

best conditions, the shallow and rocky water around the crib made it

extremely difficult for the lighthouse tender Dahlia to get any closer

than 900 feet from the crib, making filling of the gas storage tanks

extremely difficult, and with the shipping channels between Milwaukee

and Chicago frequently kept open all year, this job became virtually

impossible with the arrival of winter ice. Finally, the Pintsch gas

illumination itself proved to be extremely bothersome, and while the

contractors who installed the light were forced to return to make

adjustments to the light on a number of occasions, the quality of the light was never

considered satisfactory. In a last-ditch effort to increase the

visibility of the failing light, it was increased in height by the

addition of a twenty-foot tall skeletal iron structure atop the existing

tower in 1901 - along with the inevitable addition of twenty-five yards

of additional riprap around the base of the crib.

In what was tantamount to an admission

of failure, the Lighthouse Board requested the sum of $75,000 for the

construction of a 60-foot tall, year-round manned light station and fog

signal on the reef in its annual report for 1902. After the Secretary of

the Treasury personally wrote a letter to Congress requesting the

funding, Congress approved the appropriation of $75,000 for the

construction of the new light on March 3, 18903. Under the direction of

Captain James G. Warren of the Corps of Engineers, the draftsmen at the

Ninth District depot in Milwaukee created the plans and specifications

for what could arguably be considered one of the grandest structures

undertaken by Lighthouse Board in its half century of responsibility for

the nation's aids to navigation.

In November and December of 1904, the lighthouse tender

HYACINTH conducted a survey of an area in sixteen feet of water to the northeast of the existing

light for the new station. Over that winter, bids were advertised

for the construction of the new concrete crib, the structural steel framing and the iron and copper sheathing for the dwelling

and centrally

integrated tower. Work on the reef began the following year with the

tender DAHLIA towing the sixty-foot square timber crib out of

Racine harbor where it had been constructed, and placing it on the reef

which had been cleared to accept it. The crib was then sunk through the

addition of ballast stone into pockets within. Work then turned to the

casting of the concrete exterior of the pier and the basement engine

room, which was centrally formed within the concrete of the pier.

Finally, almost as an homage to the old light, seventy-six tons of

riprap were spread around the base of the crib. Work on the crib was

completed in October, 1905, and attention turned toward the construction

of the dwelling itself. In November and December of 1904, the lighthouse tender

HYACINTH conducted a survey of an area in sixteen feet of water to the northeast of the existing

light for the new station. Over that winter, bids were advertised

for the construction of the new concrete crib, the structural steel framing and the iron and copper sheathing for the dwelling

and centrally

integrated tower. Work on the reef began the following year with the

tender DAHLIA towing the sixty-foot square timber crib out of

Racine harbor where it had been constructed, and placing it on the reef

which had been cleared to accept it. The crib was then sunk through the

addition of ballast stone into pockets within. Work then turned to the

casting of the concrete exterior of the pier and the basement engine

room, which was centrally formed within the concrete of the pier.

Finally, almost as an homage to the old light, seventy-six tons of

riprap were spread around the base of the crib. Work on the crib was

completed in October, 1905, and attention turned toward the construction

of the dwelling itself.

The "Victorianesque" main

station building was designed with an internal skeleton of structural

steel around which an exterior skin of brick, cruciform in plan, was

laid. With four main decks, the building stood sixty-six feet from the

upper surface of the crib on which it was constructed to the top of the

lantern. At the station's lowest level, the basement engine room was

provided with a high ceiling which extended into the first deck. Large

glass "French doors" on an exterior first floor wall both

allowed light into the basement and provided a large opening through

which equipment could be moved in and out of the engine room by way of a

hoist above the doors. Outfitted with coal-fired twin boilers which

provided steam for both the ten-inch fog whistles and the station's

central heating system. A large diameter steel chimney led from the

boilers through the three living areas above to exit on the gallery, and

extended above the roof of the lantern to help move smoke from the

boilers away from the station. The "Victorianesque" main

station building was designed with an internal skeleton of structural

steel around which an exterior skin of brick, cruciform in plan, was

laid. With four main decks, the building stood sixty-six feet from the

upper surface of the crib on which it was constructed to the top of the

lantern. At the station's lowest level, the basement engine room was

provided with a high ceiling which extended into the first deck. Large

glass "French doors" on an exterior first floor wall both

allowed light into the basement and provided a large opening through

which equipment could be moved in and out of the engine room by way of a

hoist above the doors. Outfitted with coal-fired twin boilers which

provided steam for both the ten-inch fog whistles and the station's

central heating system. A large diameter steel chimney led from the

boilers through the three living areas above to exit on the gallery, and

extended above the roof of the lantern to help move smoke from the

boilers away from the station.

The main entrance to the station was gained through a

narrow steel door on the first deck above which "1906" was carved into the limestone lintel. The

door opened onto a landing with two sets of stairs, one leading down to the

engine room floor, and one up to the second deck. With a central hall connecting a galley, day room and an office,

the second floor served as the primary living area for the station, and two bedrooms and a head rounded-out

the keeper's living area on the third deck. The stairs on the third deck

lead up to the watch room, which was centered within the roof, both of which

were clad with folded-seam seamed copper sheeting. The watch room featured

four small round portholes through which the keepers could keep an eye out

for vessels in trouble. Atop the watch room, an octagonal lantern with vertical astragals contained the station's

Fourth Order Fresnel lens, which

sat atop a four-posted solid brass pedestal. The lens rotated at a relatively

high speed providing a repetitive characteristic .07 second red flash followed by 4.3

seconds of white light.

Two attached outbuildings on the crib completed the structure. One of which was used for coal storage for the boilers and the other a boathouse into which the boat was raised and swung using the steam-powered derrick on the crib. With the

exhibition of the light for the first time on a date which we have yet

been unable to determine, the old Pintsch light and tower were removed and shipped to

Chicago, where it was installed on the outer breakwater. No longer serving any purpose, the locomotive headlight on Wind Point was removed. Two attached outbuildings on the crib completed the structure. One of which was used for coal storage for the boilers and the other a boathouse into which the boat was raised and swung using the steam-powered derrick on the crib. With the

exhibition of the light for the first time on a date which we have yet

been unable to determine, the old Pintsch light and tower were removed and shipped to

Chicago, where it was installed on the outer breakwater. No longer serving any purpose, the locomotive headlight on Wind Point was removed.

The last listing for the Racine Reef

Light appeared in the Lighthouse Board annual report for 1908, stating

merely that all work on the station was complete, with the exception of

placing additional riprap for protection of the crib.

While

the station was located only a mile off the harbor, that mile proved to

be treacherous for keepers stationed at the station. While

the station was located only a mile off the harbor, that mile proved to

be treacherous for keepers stationed at the station.

At 7 am on Sunday March 1, 1908, Keeper

George Cornell left the station on a misty morning headed for shore.

Unable to see that the water between the station and shore was a field

of loosely broken ice, Cornell continued to push his way to shore. As

the wind shifted, ice began to blow towards the shore, and Cornell soon

found that he was locked fast in the ice. After an hour of sitting

hopelessly in his boat, someone on shore caught sight of the stranded

keeper and alerted a couple of fish tugs in the harbor who began

breaking a path through the ice towards Cornell. Three hours later, they

managed to break their way through to keeper Cornell, and returned him

to the station. Evidently, they arrived just in time, as the wind had

shifted, and the mass ice in which he found himself entrapped was being

pushed out to sea.

Ten years later on September 4, 1918,

William Larson who had served at the Racine Breakwater Light and was

visiting the keepers at Racine Reef was less fortunate than Cornell.

Falling from his boat on his way back to the harbor, Larson drowned when

he found himself unable to climb back into his row boat as a result of

high winds. While a search for Larson was immediately conducted, no sign

of his body could be found. A month later, Larson's body was discovered

on the beach at New Buffalo on October 9, over 100 miles to the

southeast of Racine.

At some time between 1924 and 1928 the

station's 10-inch steam powered fog whistles were replaced with

duplicate air-powered diaphone fog signals, and the sound characteristic

modified to a repetitive cycle of a 3-second blast followed by

27-seconds of silence. However, since the station was heated by steam,

and the boilers continued to be necessary, the old 10-inch fog whistles

were left in the building to serve as a backup system to the diaphones.

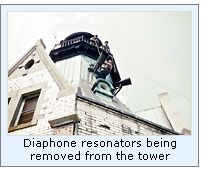

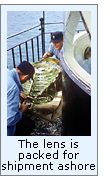

The station was electrified after the

Coast Guard assumed responsibility for the nation's aids to navigation

in 1939, and with advances in Radar and radio navigation in the early 1960's combined with

rapidly escalating maintenance costs, the Coast Guard made the difficult

decision to demolish the majestic building in 1961. To prepare for

demolition, the three-man crew assigned to the Reef were charged with

removing everything of value, including the motors, compressors,

diaphones, Fresnel lens and all of the station's furnishings.

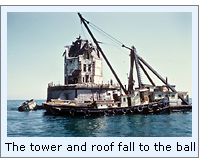

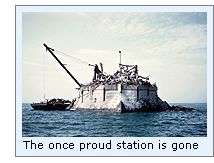

The demolition itself was undertaken by

the United States Army Corps of Engineers based out of Kewaunee. In an

ironic twist of fate, the demolition was undertaken by the sixty-six

foot tug Racine, which had been built by the Marine Iron and

Shipbuilding Company of Duluth in 1955. With the arrival of the Racine

with a wrecking barge in tow, the old station quickly fell to the

wrecking ball over a two month period in the summer of 1961. While the

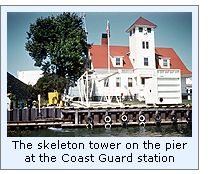

wrecking work was underway, the sections of a prefabricated skeletal

tower to be assembled on the crib was delivered at the Racine Coast

Guard station. The demolition itself was undertaken by

the United States Army Corps of Engineers based out of Kewaunee. In an

ironic twist of fate, the demolition was undertaken by the sixty-six

foot tug Racine, which had been built by the Marine Iron and

Shipbuilding Company of Duluth in 1955. With the arrival of the Racine

with a wrecking barge in tow, the old station quickly fell to the

wrecking ball over a two month period in the summer of 1961. While the

wrecking work was underway, the sections of a prefabricated skeletal

tower to be assembled on the crib was delivered at the Racine Coast

Guard station.

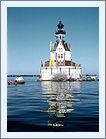

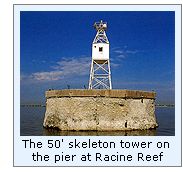

With the final remnants of the once

majestic station stripped from the crib, the new white skeletal tower

was loaded on the barge, towed out to the reef and erected on the naked

crib, where it stands to this day, its white acrylic lens flashing every

six seconds from fifty feet above the water, warning mariners of the

dangerous rocks (and uncounted tons of riprap) that still lurk beneath

the surface.

Keepers of this Light

Click Here

to see a complete listing of

all Racine Reef Light keepers compiled by Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes

Lighthouse Research.

Finding this Light

From

I-94, take Hwy 20 east. Hwy 20 eventually becomes Washington Ave. Follow

Washington Ave. to Hwy 32, and head north on Hwy 32. Turn right on

Christopher Columbus Causeway, and follow around the marina until the

road ends in a parking area. Walk the short distance to the lighthouse

at the marina entrance.

Reference Sources

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Board, 1868 through 1909.

Great Lakes Light Lists, various, 1924 through 1953.

Great Lakes Coast Pilots, various, 1952 - 2000

Photographs of Racine Reef in 1961 courtesy of Jerry Schober.

Photograph of existing light courtesy Ken & Barb Wardius, 2001.

Email interviews with Jerry Schober, October & November 2001.

The Door Count Advocate, various issues, 1906 - 1918

Keeper listings for this light appear

courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|