|

The Station Up on the ramp to my right was a well campaigned 41 foot double ended boat that looked very similar to the old 36 double ended life boats of their day except it was larger and had a partially enclosed wheel house. Her steel plating was pillowed from years of rough weather steaming. They were replacing a bent shaft from the last winter's ice ops. Amid ships in its belly, it carried a single diesel engine unlike the forty-foot boats that were twin screw. The attractive thing about the old 41 boat was that it was a displacement hull, was made of heavier steel and had an iron screw (prop) and shaft that could take a real beating in the ice. We had it for the winter months when there was ice around the island. Every year, one man was left behind to live on Washington Island as a keeper for the station while it was closed. He was expected to check on the station daily by boat if possible. The boat could be used to break the ice if it wasn't too thick.

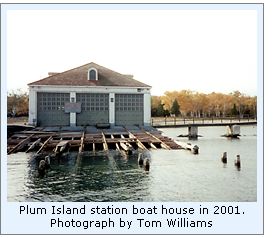

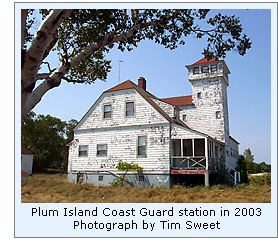

The boathouse actually sat out in the water. The pier ran along side of it and ended at the beach where a thick concrete sidewalk picked up and ran up to the front of the station house without interruption. From there, it was four or five steps up to the good-sized front porch and a right turn in the front door. You entered a vestibule where you would hang your jackets and hats. Across the front of the station was the mess deck combination dining room and lounge was with a large picture window. I remember how shocked I was to see it painted baby blue. Coast Guard regulations required eating quarters to be painted Apricot Yellow because it aided in the digestion of food. Everyone I knew hated the color but blue! Well, I got used to it. All trim was a gleaming gloss white. The deck was the familiar dark green marble swirled linoleum tile that glossed with so much wax and polishing that you could literally see your face in it. Forming the end of the building on the front towards the Pilot Island Light was a separate room that looked like a large coat closet and was in fact a radio room that was painted in the obligatory Apricot. It contained a Am radio (no static Fm was just being introduced) and an intercom to the watch shack on the other side of the island. The main radio was in the watch shack but this one was for radio ops during search and rescue (SAR) ops so that the chief could stay in communication with the boats. To the right and in the back one fourth of the building was the galley. This was painted in the imaginative and required all white finish with the typical wooded cupboard and center island food preparation table. The rest of the building was the Station Chief's office and his private quarters (room) and an attached garage where the station's Korean War vintage jeep with the canvas top was kept. Up the stairs were several rooms including a head (full bath), a large barracks type room that housed about eight single steel framed beds fondly referred top as "racks" which they were and an additional room for the rated enlisted men. At the top of the stairs was another small room that had a tall wooden ladder that ascended to the lookout tower that was by this time in disuse. Never the less, it was kept painted, clean with all windows polished. The basement was a typical basement in the regard that it was so called "unfinished" with a concrete floor, exposed wooded rafters, furnace, water tank and various pipes running along the ceiling. What was different was that it was absolutely immaculate. The floor was freshly painted in a glossy battleship gray. The cement and boulder foundation was painted a gleaming white and every pipe and piece of conduit was painted to a required shipboard color scheme that quickly identified its function. The water pipes even had little arrows hand painted on them every few inches to show the direction of water flow. It was a monthly routine to grease the water valves so they would not become frozen stuck from disuse. Outside was a second building that was the water pump house. An interesting side light about the water on Plum Island is this: it tastes like diesel fuel. That's right. Diesel fuel. You see Plum Island is typical of northern Wisconsin topography in that it is mainly sand over Dolomite rock and Lannon Stone. The only grass on the island is essentially scrub and I can't remember if we had a lawn mover or not. I believe we had a little 20" power mower but I don't believe I ever cut it the 9 months I was there. What I noticed immediately missing in your recent photo of the lifeboat station is the fuel tank. The station was heated by diesel fuel and was kept in an above ground big yellow tank that sat on a concrete base about ten yards to the east (towards Pilot Island Light) of the station house.

The station was "billeted for 12 men but there were always three on leave. Because this was considered isolated duty, we were scheduled to be at the light 4 weeks and then be compensated with one week off. This was to make it fair for those duty stations where Coasties routinely stayed aboard one night out of three to stand watches but were free to go on liberty the other two nights. I happen to take to the solitude of the island and schemed to get a ton of leave at the end of the year by staying on the light all the time. The idea was that by doing that, I could take 30 days of "compense" and then add my standard 30 days leave and actually get out of duty for a whole sixty days. In reality, having been on my own for half a year, first in boot camp in the fall of '64 and then TAD (Temporary Assigned Duty) at Group Two Rivers waiting for the ice to go out at Plum, I only stayed home for three weeks. At the age of 21, I was going stir crazy hanging around my parent's house in Minneapolis, MN with nothing to do. I ended up reporting to my new duty station aboard the USCGC Raritan (cutter) based in Milwaukee a couple weeks early and sold my time back to the service. Another man at the station was a really nice guy by the name of Leonard Farr from Massachusetts. He was a 3rd class engineman and we became friends. He was slender, red-haired and freckles. I remember his quick smile and rarely complained which is a well-known pastime in all the services. The Office-in-Charge was a genuine man by the name of Chief Gleason. He was from Alabama as I recall. He was married and his family and kids were there. The Chief was a good man as were all the men at the station that year. His main problem was that he was extraordinarily home sick. I never again saw this phenomenon in a man who had over fifteen years in the service but he was truly miserable. It never seemed to interfere in his duties that were many, but I felt very sorry for him. The man that kind of held everything together was a cheerful faced 2nd Class engineman by the name of Oldenberg. He was about 5 foot 10 inches tall, heavy set and strong from Door County on the mainland and I believe is still farming somewhere east of Fish Creek to this day. I met him the first day I arrived in the attached garage where he was changing the oil on the jeep that would spend another year trudging back and forth down the only dusty road to the light on the opposite side of the island. He was good with his hands as most farmers learn to be but was truly a natural mechanic. He maintained anything mechanical on the boats or in the station. Palmer was an EMT (Electrician's Mate) and they complimented each other well both in physical build and talents but "Olie" could do either and well. There was a "short timer" there by the name of Teslow who was a seaman first class like me but he was due to get out during that summer. He marked off his days left in the service on the wall next to his rack. I remember one night when he exclaimed that he had only 60 days to go! Then, everyone else recited how many days they had: 128. 389, 645, etc. Then, with some quick figuring, I joyously announced to my own dismay, I had only a 1028 days! The ensuing laughter was at my expense but it was funny. The cook was of medium height, blonde curly hair and deep blue eyes. I don't remember much except he could make good things out of nothing. Coast Guard cooks all took pride in that, I later learned. He made a real effort to cook things the crew liked. The food in the Coast Guard is always excellent. They are given enough money to feed every man assigned to the station but there were always three men gone on leave so, we could afford to buy better stores like steak and chicken and several kinds of fish. Yes, we did fish off the pier occasionally but the good fish in Lake Michigan are usually in deeper water. Casting was usually a recreation left for after the evening supper on a nice night.

|

In addition, the 41 boat was designed

to roll over 360 degrees and keep going in rough weather although

fortunately, that was never tested. There was a third boat on the left

side of the pier as I walked toward the station. She appeared to be more

of a little yacht than a boat. She was in fact the last of the old

lighthouse twenty-five foot tenders built back in the forties with

little cuddy-cabin and large open rear deck in launch fashion. She was

powered by a single Budha engine and was simply pretty. We never used

her much because she was slow at about 8 knots full speed so, she was

more akin to a pet than a work boat. The forty footer was everyone's

first choice because it would get up on a plane and throw a beautiful

bow spray.

In addition, the 41 boat was designed

to roll over 360 degrees and keep going in rough weather although

fortunately, that was never tested. There was a third boat on the left

side of the pier as I walked toward the station. She appeared to be more

of a little yacht than a boat. She was in fact the last of the old

lighthouse twenty-five foot tenders built back in the forties with

little cuddy-cabin and large open rear deck in launch fashion. She was

powered by a single Budha engine and was simply pretty. We never used

her much because she was slow at about 8 knots full speed so, she was

more akin to a pet than a work boat. The forty footer was everyone's

first choice because it would get up on a plane and throw a beautiful

bow spray. One year before I got there, it was a

very cold winter and the tank burst and spilled its contents on the

ground. It seeped deep into the ground and polluted the water table.

Subsequent health inspectors claimed that it was diluted enough by the

natural cleaning nature of the sand and water so that we could drink it

but it tasted and smelled God-awful. We used it for laundry and washing

but visitors always looked at us funny because I guess they could smell

the diesel "perfume". It was a daily routine to walk out to

the end of the pier with a bucket and help ourselves to Michigan's own

which was clear at sixty feet and tasted like, well, water! You'd think

that they would have installed a pump to pipe the lake water to the

house but we were not billeted for such luxuries so, it was not to be.

This water we used for cooking and drinking and was some of the best

water I have ever tasted.

One year before I got there, it was a

very cold winter and the tank burst and spilled its contents on the

ground. It seeped deep into the ground and polluted the water table.

Subsequent health inspectors claimed that it was diluted enough by the

natural cleaning nature of the sand and water so that we could drink it

but it tasted and smelled God-awful. We used it for laundry and washing

but visitors always looked at us funny because I guess they could smell

the diesel "perfume". It was a daily routine to walk out to

the end of the pier with a bucket and help ourselves to Michigan's own

which was clear at sixty feet and tasted like, well, water! You'd think

that they would have installed a pump to pipe the lake water to the

house but we were not billeted for such luxuries so, it was not to be.

This water we used for cooking and drinking and was some of the best

water I have ever tasted.