|

|

|

| Click thumbnails to view enlarged images | ||

| Minneapolis Shoal Lighthouse | Seeing The Light |

|

|

|

Historical Information Located

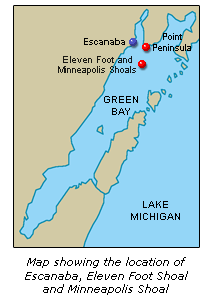

within the protection of Little Bay De Noc, Escanaba grew to become the

preeminent Lake Michigan iron ore shipping port, with vessels lining up

to load at its numerous docks to load with iron ore transported from

the Superior mines via rail. To serve the ever increasing number of

vessels making their way out of Little Bay de Noc bound for the hungry

steel mills along the southern shores of lakes Michigan and Erie, the

Lighthouse Board established a light station at the tip of Point

Peninsula in 1865 to warn of the shallows extending into the lake to

the south. Located

within the protection of Little Bay De Noc, Escanaba grew to become the

preeminent Lake Michigan iron ore shipping port, with vessels lining up

to load at its numerous docks to load with iron ore transported from

the Superior mines via rail. To serve the ever increasing number of

vessels making their way out of Little Bay de Noc bound for the hungry

steel mills along the southern shores of lakes Michigan and Erie, the

Lighthouse Board established a light station at the tip of Point

Peninsula in 1865 to warn of the shallows extending into the lake to

the south. With

the size of commercial vessels increasing with each rebuilding of the

Soo Locks, these deeper draft vessels began making their way in and out

of the bay through deeper water some 7 miles to the west of Point

Peninsula. However, this new steamer track was not without its dangers,

as captains had to thread their way around a pair of shoals which lay

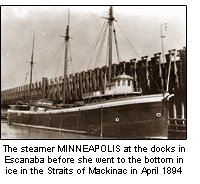

directly in their path. Eleven Foot Shoal named for the least depth of

water above its upper extent, and Minneapolis Shoal two miles to the

southwest, named for the steamer MINNEAPOLIS which went aground on the

shoal, only to go to the bottom some years later in the Straits of

Mackinac. With

the size of commercial vessels increasing with each rebuilding of the

Soo Locks, these deeper draft vessels began making their way in and out

of the bay through deeper water some 7 miles to the west of Point

Peninsula. However, this new steamer track was not without its dangers,

as captains had to thread their way around a pair of shoals which lay

directly in their path. Eleven Foot Shoal named for the least depth of

water above its upper extent, and Minneapolis Shoal two miles to the

southwest, named for the steamer MINNEAPOLIS which went aground on the

shoal, only to go to the bottom some years later in the Straits of

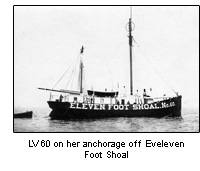

Mackinac.Mariners began lobbying for the establishment of a light to mark these shoals in the late 1880’s, and at the urging of the Lighthouse Board, Congress appropriated $60,000 for establishing such a station as part of the sundry civil appropriations bill of August 30, 1890. However, with a number of other unfunded offshore lights needed in the district, the Lighthouse Board received Congressional approval to use the appropriation for the construction of three light ships as opposed to one light station, with one of the new vessels to be placed to mark Eleven Foot Shoal.  A

contract was entered into for building the vessel on March 29, 1893

with the Craig Shipbuilding Company in Toledo The plans called for an

oak hull of 80 feet 9 inches in length and 20 feet 6 inches in the

beam. She was to be equipped with a six-inch steam whistle to be

actuated by a Warrington tube boiler, with the specification that the

vessel be able to raise sufficient steam pressure to operated the

whistle in fifteen minutes from the time the fire was lighted. The

vessel was to show three lens lanterns encircling the foremast head at

a height of 40 feet above water and visible for a distance of 13 ˝

miles in clear weather. Before launch, the vessels’ hull was painted

black with all her upper works white, and words “Eleven Foot Shoal No.

60” were painted in large white letters on each of her flanks. She was

towed to Lake Michigan and placed upon her assigned anchorage off

Eleven Foot Shoal on October 6, 1893. A

contract was entered into for building the vessel on March 29, 1893

with the Craig Shipbuilding Company in Toledo The plans called for an

oak hull of 80 feet 9 inches in length and 20 feet 6 inches in the

beam. She was to be equipped with a six-inch steam whistle to be

actuated by a Warrington tube boiler, with the specification that the

vessel be able to raise sufficient steam pressure to operated the

whistle in fifteen minutes from the time the fire was lighted. The

vessel was to show three lens lanterns encircling the foremast head at

a height of 40 feet above water and visible for a distance of 13 ˝

miles in clear weather. Before launch, the vessels’ hull was painted

black with all her upper works white, and words “Eleven Foot Shoal No.

60” were painted in large white letters on each of her flanks. She was

towed to Lake Michigan and placed upon her assigned anchorage off

Eleven Foot Shoal on October 6, 1893.Five years later, a thirty foot red and black horixontaly striped spar buoy was placed to more clearly mark the shallowest part of Minneapolis Shoal on July 8, 1893. For the following three decades, the light vessel was typically removed from her station in mid December and taken to winter quarters in Sturgeon Bay, where she also frequently underwent repairs during layover. Freshened and declared fit for service for another season she was then returned to her station after ice breakup in late April. After  thirty three years of service, it was clear the venerable oak hulled vessel had seen her best days and

with a navigational aid to mark the shoals still considered imperative,

the Commissioner of Lighthouses was faced with the expensive

proposition of either replacing her or constructing a permanent light

station on the shoal. thirty three years of service, it was clear the venerable oak hulled vessel had seen her best days and

with a navigational aid to mark the shoals still considered imperative,

the Commissioner of Lighthouses was faced with the expensive

proposition of either replacing her or constructing a permanent light

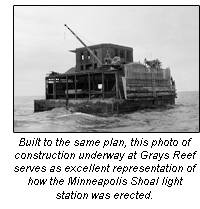

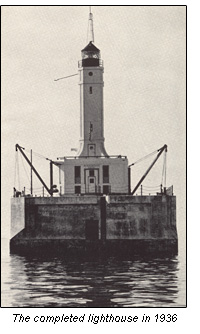

station on the shoal. Commissioner Putnam decided to punt, deciding to sell the old vessel and to place a relief lightship in her place until the financial climate was considered more amenable to a request for funding a permanent solution. To this end, Light Vessel Number 60 was sold at public auction on January 15, 1926. She changed hands a number of times over the ensuing years, eventually being purchased by the Chicago Yacht Club to serve as a floating club house, after which service she was scrapped. After lighting the shoals with a succession of relief vessels over the subsequent decade, by the early 1930’s the Commissioner finally deemed appropriate to seek funding to replace the lightship with a permanent light station, and Congress appropriated $155,000 for its construction on Minneapolis Shoal as part of the Public Works Administration Act of July 18, 1933. The contract for construction of the new lighthouses was awarded to B J Gallagher of Escanaba.  Construction

of the 60 foot square by 20 feet tall foundation crib with 49 inner

pockets was reported as being underway in that city in May of 1934. The

crib was then towed out to a prepared area on the site and its inner 25

pockets filled with stone and its outer 24 pockets filled with

concrete, firmly securing the massive timber structure to the bottom.

Work had just begun on pouring the concrete pier atop the crib when

winter’s advance put an end to construction work for the season.

Returning to the site in the spring of 1935, Gallagher’s crew poured a

solid slab of concrete six feet thick atop the submerged crib and

formed an outer wall of concrete six feet thick curved inward on the

outside face to deflect waves. Over the top of this base, a one foot

thick slab of concrete was poured to form the working deck, which was

enclosed by a heavy iron railing. At this point, a temporary lens

lantern was installed on a pole, and the lightship was permanently

removed from duty Construction

of the 60 foot square by 20 feet tall foundation crib with 49 inner

pockets was reported as being underway in that city in May of 1934. The

crib was then towed out to a prepared area on the site and its inner 25

pockets filled with stone and its outer 24 pockets filled with

concrete, firmly securing the massive timber structure to the bottom.

Work had just begun on pouring the concrete pier atop the crib when

winter’s advance put an end to construction work for the season.

Returning to the site in the spring of 1935, Gallagher’s crew poured a

solid slab of concrete six feet thick atop the submerged crib and

formed an outer wall of concrete six feet thick curved inward on the

outside face to deflect waves. Over the top of this base, a one foot

thick slab of concrete was poured to form the working deck, which was

enclosed by a heavy iron railing. At this point, a temporary lens

lantern was installed on a pole, and the lightship was permanently

removed from duty  Work

then began on the lighthouse itself, which was prefabricated of sheet

and rolled steel throughout. After erection, the steel walls were lined

with concrete block to provide insulation and increase structural

rigidity. The main level of the lighthouse served as the power room,

the floor of which was cast into the crib. its high walls extending up

into the main structure. This large room contained diesel powered

generators to supply electricity, diesel powered compressors to supply

air to the duplicate Type F diaphone fog signals and an oil-fired

boiler which provided steam heat to radiators throughout the building.

The second floor served as quarters for the keepers. Atop the flat

steel roof with a railing around its outer edge, the square tower

enclosed the diaphone resonators and a stairway winding up to the steel

lantern outfitted with helical astragals to ensure maximum light

emission. Within the lantern, an electric lamp illuminated a Fourth

Order Fresnel lens emitting 20,000 candlepower, its station

characteristic occulting light showing a flash of 4 seconds followed by

an eclipse of 2 seconds visible from a distance of 27 miles. The entire

steel superstructure received a coat of cream-colored paint and the

light officially placed into service on the night of June 30, 1936. Work

then began on the lighthouse itself, which was prefabricated of sheet

and rolled steel throughout. After erection, the steel walls were lined

with concrete block to provide insulation and increase structural

rigidity. The main level of the lighthouse served as the power room,

the floor of which was cast into the crib. its high walls extending up

into the main structure. This large room contained diesel powered

generators to supply electricity, diesel powered compressors to supply

air to the duplicate Type F diaphone fog signals and an oil-fired

boiler which provided steam heat to radiators throughout the building.

The second floor served as quarters for the keepers. Atop the flat

steel roof with a railing around its outer edge, the square tower

enclosed the diaphone resonators and a stairway winding up to the steel

lantern outfitted with helical astragals to ensure maximum light

emission. Within the lantern, an electric lamp illuminated a Fourth

Order Fresnel lens emitting 20,000 candlepower, its station

characteristic occulting light showing a flash of 4 seconds followed by

an eclipse of 2 seconds visible from a distance of 27 miles. The entire

steel superstructure received a coat of cream-colored paint and the

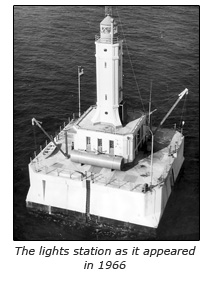

light officially placed into service on the night of June 30, 1936.Minneapolis Shoal light was manned by four man crews based out of Escanaba. With a standard work schedule of three weeks on the light and one on shore leave, three men were always on the light with the nexception of that short period wnen the shore leave swap was undertaken using the station boat. As was the case at most of the offshore crib lights, life at Minneapolis Shoal was largely one of strict routine and boredom, as would be expected living in an isolated world that was only sixty feet square. Fortunately, the fishing was good, and the men would run out lines with bells on them. Fish would be hauled up and placed in a large live box which would be carried into the kitchen where the crew would filet, clean and cook them in assembly line fashion.  Beginning

in the 1960's, the Coast Guard Ninth District embarked on an initiative

known as the Lighthouse Automation Project (LAMP.) This initiative

called for the systematic automation of all offshore

lights followed by the shore lights, and by 1977 Minneapolis Shoal was

one of only five remaining manned offshore lights in the Great Lakes,

the others being Detroit River, Thunder Bay Island, North Manitou Shoal

and Green Bay Harbor Entrance. Beginning

in the 1960's, the Coast Guard Ninth District embarked on an initiative

known as the Lighthouse Automation Project (LAMP.) This initiative

called for the systematic automation of all offshore

lights followed by the shore lights, and by 1977 Minneapolis Shoal was

one of only five remaining manned offshore lights in the Great Lakes,

the others being Detroit River, Thunder Bay Island, North Manitou Shoal

and Green Bay Harbor Entrance. Minneapolis Shoal was finally automated in 1979 and later updated to a 12-volt DC system powered by photovoltaic panels. When we last saw this lighthouse in 2010, its illumination was being provided by a Vega VRB-25 rotating beacon. If not already changed, it is inevitable that this Vega unit will be replaced by one of the LED units which are currently being installed to replace all the lights on the Great Lakes.

Seeing

this Light GPS Coordinates 45°34'53.34"N x 86°59'54.71"W |