|

|

|

| Click thumbnails to view enlarged images 84°46'22.86"W | ||

| McGulpin Point Lighthouse | Seeing The Light |

|

|

|

|

Historical Information The

promontory which would become known as McGulpin Point has a history

which starts perhaps thousands of years ago with Native American use

and continues into the 20th Century as a lighthouse location. According

to the oral traditions of the Anishnaabek, Native Americans arrived and

settled in the Straits of Mackinac many generations before the arrival

of the first Europeans. Anishnaabek history tells of the Odawa coming

to the Straits of Mackinac to expel an earlier tribe living in Northern

Michigan. According to Odawa historian Andrew J. Blackbird, this tribe

was called the Mus-co-desh. In Blackbird’s story, a great insult was

delivered to the Odawa by the Mus-co-desh, who then occupied what is

now Emmet County. This insult so infuriated the great war chief Sagemaw

that he immediately went back to his villages on Manitoulin Island to

gather a war party to right this wrong. The result was the near

extermination of the Mus-co-desh and their expulsion from Northern

Michigan. The Odawa took advantage of this vacuum and moved into Emmet

County, first settling at McGulpin Point.

American

written history tells us that John McAlpine and his Native American

wife lived on McGulpin Point in the 1760s. After the turbulence of the

Revolutionary War the land was surveyed for the new United States of

America by Aaron Greeley and ownership was determined. John McAlpine’s

son and heir, Patrick McGulpin, was given the patent on this land and

holds the first recorded deed in Emmet County, Michigan in 1811. American

written history tells us that John McAlpine and his Native American

wife lived on McGulpin Point in the 1760s. After the turbulence of the

Revolutionary War the land was surveyed for the new United States of

America by Aaron Greeley and ownership was determined. John McAlpine’s

son and heir, Patrick McGulpin, was given the patent on this land and

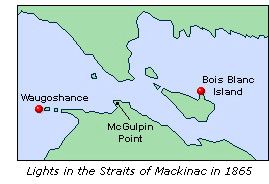

holds the first recorded deed in Emmet County, Michigan in 1811.With the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, Americans started to flood to the Chicago area. During the 1850s, vessel traffic through the Straits of Mackinac was increasing rapidly, and while the Waugoshance Light marked the western entry into the Straits, and the Bois Blanc Island light marked the eastern entry, the absence of a navigational aid within the shoal-ridden Straits themselves made passage during darkness and periods of low visibility extremely dangerous. To answer that need, the Lighthouse Board petitioned Congress for the construction of a lighthouse and fog bell at McGulpin Point, approximately two miles west of Fort Michilimackinac. Congress responded favorably to the request on August 3, 1854 with the appropriation of $6,000 for the station’s construction.  However,

as a result of difficulties in obtaining clear title to the land, no

action was taken on the station’s construction for more than a decade.

With the original appropriation unspent and expired, the Board again

petitioned Congress for the construction of a station at McGulpin Point

in 1864, this time receiving $20,000 for the project on July 26, 1866. However,

as a result of difficulties in obtaining clear title to the land, no

action was taken on the station’s construction for more than a decade.

With the original appropriation unspent and expired, the Board again

petitioned Congress for the construction of a station at McGulpin Point

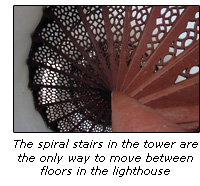

in 1864, this time receiving $20,000 for the project on July 26, 1866.Work began at McGulpin Point early in 1869, and the station was built as a mirror image of the design used at Chambers Island and Eagle Bluff lights under construction in the Door County area that same year. This plan, which is sometimes referred to as the “Norman Gothic” style, was also later also used at Eagle Harbor in 1871, White River in 1875, and at Passage and Sand Islands in 1882. The keepers dwelling and integrated tower were constructed of Cream City brick with the tower integrated diagonally into the northwest corner of the dwelling. The first and second stories of the tower were approximately ten feet square with buttressed corners, while the tower’s upper portion consisted of a ten-foot octagon. Similar to other stations built on this plan, the tower is double-walled with a circular inner wall approximately four inches thick and eight feet in diameter to house a set of cast iron spiral stairs. The tower was capped with a prefabricated decagonal cast-iron lantern and outfitted with a fixed white Third-and-a-half Order Fresnel lens.  The

building sat on a full basement, which contained two general-purpose

areas and an oil storage room. For transport of supplies into the

tower, the cast iron spiral stairs connected the oil room to the tower,

and they served as the only stairs between the living areas with

landings and doors on the first and second floors. The first floor

contained a parlor, kitchen and two bedrooms, and the second floor

featured two additional bedrooms and a large closet. Almost as an

afterthought, a combined wood shed & summer kitchen was built

in

the form of an addition to the rear of the building. The

building sat on a full basement, which contained two general-purpose

areas and an oil storage room. For transport of supplies into the

tower, the cast iron spiral stairs connected the oil room to the tower,

and they served as the only stairs between the living areas with

landings and doors on the first and second floors. The first floor

contained a parlor, kitchen and two bedrooms, and the second floor

featured two additional bedrooms and a large closet. Almost as an

afterthought, a combined wood shed & summer kitchen was built

in

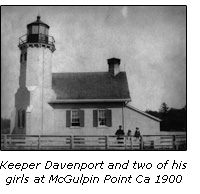

the form of an addition to the rear of the building. Among

the Station’s most notable keepers was James Davenport, who after

serving at Waugoshance and Little Point Sable, was transferred to

McGulpin Point in September of 1879. He held this position twenty-seven

years, until the station was discontinued in 1906. The Davenport family

lived the entire navigation season in the lighthouse. After the close

of the navigation season every year, they moved into to their home in

Mackinaw City so that the children could get to and from school, the

snow making the trip from town to the lighthouse virtually impossible. Among

the Station’s most notable keepers was James Davenport, who after

serving at Waugoshance and Little Point Sable, was transferred to

McGulpin Point in September of 1879. He held this position twenty-seven

years, until the station was discontinued in 1906. The Davenport family

lived the entire navigation season in the lighthouse. After the close

of the navigation season every year, they moved into to their home in

Mackinaw City so that the children could get to and from school, the

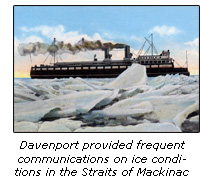

snow making the trip from town to the lighthouse virtually impossible.Correspondence files in the National Archives in Washington show that Davenport made weekly trips through the snow to the lighthouse to report on its condition to the District Inspector in Milwaukee. Perhaps more importantly, these letters also show that he may have played a critical role in the opening of navigation every spring by reporting weekly, and sometimes even more frequently, on ice conditions in the Straits. Awareness of "ice-out" in the Straits was critical to mariners, since the melting of the ice opened navigation to the critical ports of Chicago and Milwaukee.  Because

Davenport was the only Straits keeper to submit such frequent reports,

it would appear that the Inspector used these reports to gain an

understanding as to when navigation would be open throughout the lakes.

Most of Davenport’s weekly winter reports consisted of terse commentary

as exemplified by his letter of March 28, 1890 in which he reported

“Sir, Ice in the Straits between here and Mackinac Island is broke up

some so that it moved a little with the heavy E. wind last night. But

no water to be seen west of this station as far as can be seen with a

glass. The ice is good and solid. Teams crossed the Straits yesterday.

Lake Huron is clear of ice up to Mackinac Island. This station is in

good order.” Davenport was absolutely meticulous in filing these

reports on a weekly basis with the exception of a single week in 1891,

when he missed filing his report. His sad letter of March 23rd of that

same year provided the reason for his missing the report, when he wrote

“Sir, I just was up in the Lt House and found all in good order. You

will see by this report that I did not report to you last week. My wife

and child died last week and I could not go up to the light house to

report to you as required.” Because

Davenport was the only Straits keeper to submit such frequent reports,

it would appear that the Inspector used these reports to gain an

understanding as to when navigation would be open throughout the lakes.

Most of Davenport’s weekly winter reports consisted of terse commentary

as exemplified by his letter of March 28, 1890 in which he reported

“Sir, Ice in the Straits between here and Mackinac Island is broke up

some so that it moved a little with the heavy E. wind last night. But

no water to be seen west of this station as far as can be seen with a

glass. The ice is good and solid. Teams crossed the Straits yesterday.

Lake Huron is clear of ice up to Mackinac Island. This station is in

good order.” Davenport was absolutely meticulous in filing these

reports on a weekly basis with the exception of a single week in 1891,

when he missed filing his report. His sad letter of March 23rd of that

same year provided the reason for his missing the report, when he wrote

“Sir, I just was up in the Lt House and found all in good order. You

will see by this report that I did not report to you last week. My wife

and child died last week and I could not go up to the light house to

report to you as required.” December

5, 1893 was a particularly eventful one at McGulpin Point when the

wooden propeller WALDO A. AVERY caught fire while passing through the

Straits. By the time the vessel was off McGulpin Point, the fire was

raging so badly that in order to save his crew, the captain steered the

vessel toward the lighthouse at full steam. Keeper Davenport had left

the station for Mackinaw City earlier in the day, and with the

aforementioned passing of his wife two years prior, had left his nine

children alone at the station. Accustomed to lighthouse life, the

children were a resourceful group, and made preparations for the care

of the survivors. Imagine the fear in the children’s hearts as they saw

the crew members literally fighting for their lives on the approaching

vessel. Alerted to what was going on at the lighthouse, Davenport

rushed back to the station with a number of Mackinaw City residents.

With the vessel’s lifeboat burned and unusable, numerous trips to the

burning and beached vessel were made with the Station’s small skiff,

until all seventeen crew members had been brought to safety on the

shore. The AVERY’s insurance for the season had expired the previous

day, and while the vessel was declared a complete loss at the time, the

hull was recovered in 1894. The vessel was rebuilt, and continued to

ply the lakes until she was finally abandoned in 1923. December

5, 1893 was a particularly eventful one at McGulpin Point when the

wooden propeller WALDO A. AVERY caught fire while passing through the

Straits. By the time the vessel was off McGulpin Point, the fire was

raging so badly that in order to save his crew, the captain steered the

vessel toward the lighthouse at full steam. Keeper Davenport had left

the station for Mackinaw City earlier in the day, and with the

aforementioned passing of his wife two years prior, had left his nine

children alone at the station. Accustomed to lighthouse life, the

children were a resourceful group, and made preparations for the care

of the survivors. Imagine the fear in the children’s hearts as they saw

the crew members literally fighting for their lives on the approaching

vessel. Alerted to what was going on at the lighthouse, Davenport

rushed back to the station with a number of Mackinaw City residents.

With the vessel’s lifeboat burned and unusable, numerous trips to the

burning and beached vessel were made with the Station’s small skiff,

until all seventeen crew members had been brought to safety on the

shore. The AVERY’s insurance for the season had expired the previous

day, and while the vessel was declared a complete loss at the time, the

hull was recovered in 1894. The vessel was rebuilt, and continued to

ply the lakes until she was finally abandoned in 1923. With

the construction of the Old Mackinac Point light and fog signal station

in 1892, the Lighthouse Board decided that McGulpin point station no

longer served its once critical role, since the new light at Old

Mackinac Point was visible from throughout the Straits, whereas

McGulpin Point was only effectively visible from the west. The

Lighthouse Board officially authorized the discontinuance of McGulpin

point on November 12, 1906, and keeper Davenport climbed the stairs to

exhibit his light for the last time on the closing of the navigation

season on December 15 of that year. With

the construction of the Old Mackinac Point light and fog signal station

in 1892, the Lighthouse Board decided that McGulpin point station no

longer served its once critical role, since the new light at Old

Mackinac Point was visible from throughout the Straits, whereas

McGulpin Point was only effectively visible from the west. The

Lighthouse Board officially authorized the discontinuance of McGulpin

point on November 12, 1906, and keeper Davenport climbed the stairs to

exhibit his light for the last time on the closing of the navigation

season on December 15 of that year.  The station

was

boarded-up and the

lantern and lens removed, with Davenport serving as caretaker for a few

weeks until his transfer to Mission Point lighthouse where he continued

to serve until his retirement in 1917. On retirement, he returned to

Mackinaw City, where he lived-out the remainder of his life, passing

away on March 18, 1932 at the age of eighty-five. The station

was

boarded-up and the

lantern and lens removed, with Davenport serving as caretaker for a few

weeks until his transfer to Mission Point lighthouse where he continued

to serve until his retirement in 1917. On retirement, he returned to

Mackinaw City, where he lived-out the remainder of his life, passing

away on March 18, 1932 at the age of eighty-five.While records show that McGulpin Point’s lens was temporarily stored at Old Mackinac Point lighthouse, the eventual disposition of both the station’s lens and lantern remain undetermined. Approval was issued by the Board to sell the lighthouse at auction on May 22, 1907, and advertisements of the sale were published in the Cheboygan, Chicago, Detroit and Milwaukee newspapers with sealed bids received to be opened on July 17. The highest bid received was only for $875, and with the District Inspector feeling that it was worth at least twice that much, the bid was rejected, and the property sat unused.  Over

the ensuing years, correspondence concerning the station included a

possible transfer to Mackinac State Historic Parks and use of the

station dock and dwelling during the construction of White Shoal

lighthouse, but neither of these options reached fruition. The

lighthouse finally passed into private ownership on July 30, 1913 when

a Sam Smith, an early Mackinaw City president and entrepreneur,

purchased the property for $1,425. The station was subsequently resold

a couple of times, last being owned by the Peppler family, from whom

the station was purchased by Emmet County in 2008. Over

the ensuing years, correspondence concerning the station included a

possible transfer to Mackinac State Historic Parks and use of the

station dock and dwelling during the construction of White Shoal

lighthouse, but neither of these options reached fruition. The

lighthouse finally passed into private ownership on July 30, 1913 when

a Sam Smith, an early Mackinaw City president and entrepreneur,

purchased the property for $1,425. The station was subsequently resold

a couple of times, last being owned by the Peppler family, from whom

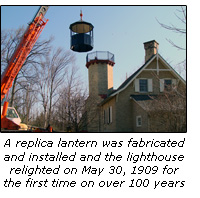

the station was purchased by Emmet County in 2008. Soon

after purchasing the lighthouse, the County formed a Historical

Commission to plan and oversee the restoration and interpretation of

the lighthouse, with GLLKA's Straits Coordinator Sandy

Planisek serving

as Chair of this Commission, and GLLKA President Dick Moehl

serving as one of the Commissioners.. Emmet County’s mission is to

reestablish McGulpin Point Lighthouse as a private aid to

navigation

(PATON). The U.S. Coast Guard has approved the McGulpin Point

Lighthouse PATON application, and a contract was let late in 2008 to

Moran Iron Works, Inc. of Onaway, MI to construct a replica decagonal

lantern. Soon

after purchasing the lighthouse, the County formed a Historical

Commission to plan and oversee the restoration and interpretation of

the lighthouse, with GLLKA's Straits Coordinator Sandy

Planisek serving

as Chair of this Commission, and GLLKA President Dick Moehl

serving as one of the Commissioners.. Emmet County’s mission is to

reestablish McGulpin Point Lighthouse as a private aid to

navigation

(PATON). The U.S. Coast Guard has approved the McGulpin Point

Lighthouse PATON application, and a contract was let late in 2008 to

Moran Iron Works, Inc. of Onaway, MI to construct a replica decagonal

lantern. At a major major maritime event on May 30, 2009 the McGulpin Point lighthouse was reopened and relighted as an official Private Aid to Navigation on May 30, 2009, 103 years after it was extinguished. Emmet

Cunty is taking the entire light station trhrough a complete

restoration and opens the lighthouse seven days a week. Hours

are noon

to 5:00 PM

in May and October and from 10:00 AM to 8 PM from June through

September. To visit McGulpin Point, take Central Avenue west underneath I-75 and continue west approximately 2 miles until the road ends at a "T" intersection. Turn right at the "T" and the lighthouse is on the right side of the street just before the road descends down to lake level. There is parking on both sides of the street. Call 231-436-5860 of email info@emmetcounty.org for information. GPS

Coordinates: 45°47'13.64"N x 84°46'22.86"W |