|

Historical

Information

Although the first sawmill had been established on the banks of the

Manistee in 1841, settlement in the area was not widespread until the

Chippewa relinquished their reservation by treaty in 1849, and the

federal government offered lands along the Manistee for public sale. It

did not take lumber interests long to realize the incredible potential

of the Manistee which snaked a hundred miles into the forests, and

lumbermen soon began lobbying for federal funding to improve the harbor

and to erect a lighthouse at the river mouth. With no appropriation

forthcoming, the businessmen of Manistee took the matter into their own

hands, erecting a pair of short stub piers at the river mouth in an

attempt to stem the deposition of sand and silt.

In 1861, Congress instructed the Army Corps of Engineers to dispatch

an Engineer Officer to Manistee to conduct a survey of the river

entrance. Water depth in the opening between the piers was found to be

from seven to eight feet, and a 250-foot long sand bar with a water

depth of less than five feet above it was identified 600 feet off the

end of the piers. While the Engineer’s report indicated that harbor

improvements at Manistee were both necessary and valid, nothing would be

done until 1867 when appropriations were simultaneously approved for

improvements to the river entrance and for the erection of a lighthouse

to guide vessels into the new entry on its completion. A survey party

was sent to Manistee in 1876 to select and survey a site on the north

shore of the river mouth for the new lighthouse reservation. While the

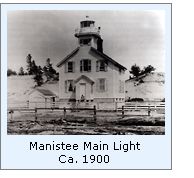

new Manistee Light

was completed in 1870, a devastating fire swept though the area on

October 6, 1871, completely destroying the to its foundation. Congress

appropriated funds for the construction of a new lighthouse which was

erected the following year. In 1861, Congress instructed the Army Corps of Engineers to dispatch

an Engineer Officer to Manistee to conduct a survey of the river

entrance. Water depth in the opening between the piers was found to be

from seven to eight feet, and a 250-foot long sand bar with a water

depth of less than five feet above it was identified 600 feet off the

end of the piers. While the Engineer’s report indicated that harbor

improvements at Manistee were both necessary and valid, nothing would be

done until 1867 when appropriations were simultaneously approved for

improvements to the river entrance and for the erection of a lighthouse

to guide vessels into the new entry on its completion. A survey party

was sent to Manistee in 1876 to select and survey a site on the north

shore of the river mouth for the new lighthouse reservation. While the

new Manistee Light

was completed in 1870, a devastating fire swept though the area on

October 6, 1871, completely destroying the to its foundation. Congress

appropriated funds for the construction of a new lighthouse which was

erected the following year.

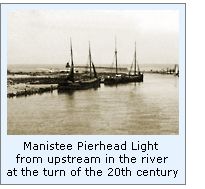

1874 and 1875 were exceptionally busy years for Manistee, with 3,488,

vessels entering the river between June 30, 1874, and June 30, 1875. To

serve this burgeoning maritime commerce, the piers were extended an

additional 150 feet in 1875, and the channel between them dredged to a

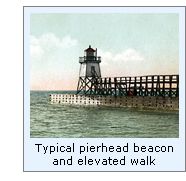

minimum depth of ten feet. With the main light now standing a

considerable distance to the rear of the pierheads, the decision was

made to replace the shore light on the north bank with a pierhead beacon

on the outer end of the longer south pier.  The new south pierhead light

consisted of a timber-framed pyramidal beacon typical of the type being

erected on pierheads throughout the Great Lakes. With its lower half

open, the upper half immediately below the gallery was enclosed to

provide a small service room for lamp maintenance. Equipped with

windows, the service room also served as a sheltered area in which the

keeper could stand watch during inclement weather. Standing 27 feet in

height, the beacon was capped with a square gallery with iron handrails

and an octagonal cast iron lantern installed at its center. The fixed

red Fifth Order lens was removed from the main light and reinstalled in

the new beacon, where its 35-foot focal plane afforded a range of

visibility of 11 miles in clear weather. An elevated timber walkway lead

from shore to a door in the service room, allowing the keepers to access

the light in relative safety when storm-driven waves crashed across the

surface of the pier. Keeper McKee rowed across the river to exhibit the

new light on the night of October 15, 1875, and with the establishment

of the new light, the main light was officially discontinued.

The new south pierhead light

consisted of a timber-framed pyramidal beacon typical of the type being

erected on pierheads throughout the Great Lakes. With its lower half

open, the upper half immediately below the gallery was enclosed to

provide a small service room for lamp maintenance. Equipped with

windows, the service room also served as a sheltered area in which the

keeper could stand watch during inclement weather. Standing 27 feet in

height, the beacon was capped with a square gallery with iron handrails

and an octagonal cast iron lantern installed at its center. The fixed

red Fifth Order lens was removed from the main light and reinstalled in

the new beacon, where its 35-foot focal plane afforded a range of

visibility of 11 miles in clear weather. An elevated timber walkway lead

from shore to a door in the service room, allowing the keepers to access

the light in relative safety when storm-driven waves crashed across the

surface of the pier. Keeper McKee rowed across the river to exhibit the

new light on the night of October 15, 1875, and with the establishment

of the new light, the main light was officially discontinued.

While the main light no longer served as an aid to navigation, the

structure continued to serve as the keeper’s dwelling, and thus the

keeper was forced to row across the river numerous times during each day

and night to tend the pierhead light. However, McKee’s inconvenience

was short-lived, as he was removed from his position on October 26, 1875

and William King appointed as his replacement.

With work continuing on the piers in 1879, the pierhead beacon was

moved 156 feet to the revised end of the south pier, and the elevated

walk extended to fill the resulting gap. The following year, the

dwelling was thoroughly repaired, and a new well sunk to provide a

supply of fresh drinking water for Keeper King and his family.

Traffic in and out of the river continued to increase throughout the

1880’s. To better serve this traffic, Eleventh District Engineer Major

Samuel M. Mansfield recommended an appropriation of $5,000 for the

erection of a fog signal on the south pier to serve as a guide to

mariners during thick or foggy weather in his report for 1888. Congress

responded with the requested appropriation on March 2, 1889, and bids

for furnishing the labor, construction materials and mechanical

equipment were advertised and awarded that same year. The following

spring, a work crew arrived at Manistee to undertake a number of

improvements on the south pier.

First, a tubular lantern was erected on a pole at the outer end of

the newly extended south pier to serve as a front range for the pierhead

beacon. The lantern was suspended from a cable which passed around a

pair of pulleys, with one pulley secured to the pole at the at the

pierhead, and the other inside a window installed on the lakeward side

of the beacon service room. This system was designed to allow the keeper

to service the tubular lantern from within the confines of the service

room, and then transport the light out along the cable to the pierhead.

After completion of this new light, the crew turned its attention to the

erection of the new fog signal building.

Typical of such structures being erected throughout the Great Lakes,

the fog signal building was built on the pier immediately behind the

beacon, and connected to the beacon by a short length of elevated walk.

Timber-framed, and sheathed with brown-painted corrugated iron sheeting,

the structure housed a pair of horizontal boilers piped to a pair of

10-ich locomotive whistles installed atop the roof. The interior of the

structure was also outfitted with a coal bin, water supply tank and a

work bench to give the keepers an area on which to perform maintenance

on the signal equipment. Construction of the new building continued

through the winter, with the signals finally tested and placed into

operation on February 10, 1890. With the establishment of the new fog

signal, the decision was made to add an assistant to the station’s

roster, with John Langland Jr. arriving to fill the position on January

15. Typical of such structures being erected throughout the Great Lakes,

the fog signal building was built on the pier immediately behind the

beacon, and connected to the beacon by a short length of elevated walk.

Timber-framed, and sheathed with brown-painted corrugated iron sheeting,

the structure housed a pair of horizontal boilers piped to a pair of

10-ich locomotive whistles installed atop the roof. The interior of the

structure was also outfitted with a coal bin, water supply tank and a

work bench to give the keepers an area on which to perform maintenance

on the signal equipment. Construction of the new building continued

through the winter, with the signals finally tested and placed into

operation on February 10, 1890. With the establishment of the new fog

signal, the decision was made to add an assistant to the station’s

roster, with John Langland Jr. arriving to fill the position on January

15.

The volume of traffic along the coast heading to and from the Straits

continued to increase, and in 1893 the decision was made to reactivate

the old main light to serve double duty as both a coast light and to

better guide mariners to the river mouth. The futility of having the

keepers simultaneously attend the reactivated main light on the north

side of the river and the fog signal and the ranges on the south pier

became clear, and thus plans were also put in place to relocate the fog

signal and pierhead light to the north pier at the opening of the

following navigation season.

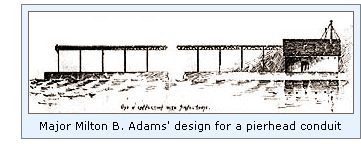

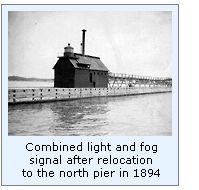

In May of 1894, a work crew arrived at Manistee moved the fog signal

building from the south pier to a new timber foundation that had been

erected 300 feet from the outer end of the north pier. Rather than

relocating the old pierhead beacon, Major Milton B. Adams instead

decided to install one of his newly designed conduit systems on the

north pierhead. Supported by trestles, a wooden conduit box lead from

the pierhead, 290 feet to an opening in the lakeward wall of the fog

signal building. The conduit contained a set of iron rails on which a

steel trolley was located. The lens was mounted atop this trolley, and

could be moved back and forth within the conduit from the fog signal

building to the pierhead. 460 feet of new elevated walk was also

installed from the rear of the fog signal building toward the shore. The

old elevated walk was then removed from the south pier, and 463 feet of

it reinstalled on the north pier, bringing the total length of elevated

walk on the north pier to 923 feet. The old Main Light was reactivated

on June 18, 1894, and the ranges on the south pier discontinued and

removed. In May of 1894, a work crew arrived at Manistee moved the fog signal

building from the south pier to a new timber foundation that had been

erected 300 feet from the outer end of the north pier. Rather than

relocating the old pierhead beacon, Major Milton B. Adams instead

decided to install one of his newly designed conduit systems on the

north pierhead. Supported by trestles, a wooden conduit box lead from

the pierhead, 290 feet to an opening in the lakeward wall of the fog

signal building. The conduit contained a set of iron rails on which a

steel trolley was located. The lens was mounted atop this trolley, and

could be moved back and forth within the conduit from the fog signal

building to the pierhead. 460 feet of new elevated walk was also

installed from the rear of the fog signal building toward the shore. The

old elevated walk was then removed from the south pier, and 463 feet of

it reinstalled on the north pier, bringing the total length of elevated

walk on the north pier to 923 feet. The old Main Light was reactivated

on June 18, 1894, and the ranges on the south pier discontinued and

removed.

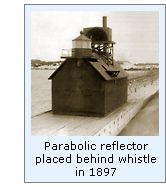

With a continuing increase in maritime commerce through the late

nineties, Manistee was in a state of metamorphosis. Undergoing the

inevitable "gentrification" that results from a massive influx

of business people and wealth, many of the newer residents found their

sensibilities insulted by the caterwauling of the fog whistle out on the

north pierhead, and began raising their voices in both disgust and

concern. A similar set of circumstances had unfolded previously at the

Duluth South Breakwater Light in 1895, where the sound of the fog signal

bounced from the hillsides around the harbor, upsetting the city

residents. Needing the support of the local maritime community, the

Lighthouse Board had undertaken an experiment whereby a large wooden

parabolic reflector had been constructed around the Duluth whistles.

Designed to concentrate the sound on the lake side of the whistle, while

simultaneously shielding the city side from much of the noise, the

experiment had been considered to be an unqualified success. Thus the

decision was made to undertake a similar modification to the Manistee

whistles, and a crew arrived at Manistee in 1897 and crafted a reflector

framework of pine, sheathed in iron and packed with sawdust to deaden

the sound. The whistles were then re-piped into the center of the

reflector, and a semblance of peace restored to the citizenry of

Manistee. With a continuing increase in maritime commerce through the late

nineties, Manistee was in a state of metamorphosis. Undergoing the

inevitable "gentrification" that results from a massive influx

of business people and wealth, many of the newer residents found their

sensibilities insulted by the caterwauling of the fog whistle out on the

north pierhead, and began raising their voices in both disgust and

concern. A similar set of circumstances had unfolded previously at the

Duluth South Breakwater Light in 1895, where the sound of the fog signal

bounced from the hillsides around the harbor, upsetting the city

residents. Needing the support of the local maritime community, the

Lighthouse Board had undertaken an experiment whereby a large wooden

parabolic reflector had been constructed around the Duluth whistles.

Designed to concentrate the sound on the lake side of the whistle, while

simultaneously shielding the city side from much of the noise, the

experiment had been considered to be an unqualified success. Thus the

decision was made to undertake a similar modification to the Manistee

whistles, and a crew arrived at Manistee in 1897 and crafted a reflector

framework of pine, sheathed in iron and packed with sawdust to deaden

the sound. The whistles were then re-piped into the center of the

reflector, and a semblance of peace restored to the citizenry of

Manistee.

Adams’ experiment with his new conduit system proved to be less

than successful, and the system at Manistee was removed from the north

pierhead in 1900. At the same time, the fog signal building was moved

260 feet to a point 42 feet from the pierhead, and installed atop a

two-foot high timber foundation. A gallery and octagonal cast iron

lantern were then installed on the lakeward gable end of the fog signal

building, and the lantern outfitted with a new fixed red Sixth Order

Fresnel lens. To clear the new lantern, the fog whistle and deflector

were raised by 4 feet. Adams’ experiment with his new conduit system proved to be less

than successful, and the system at Manistee was removed from the north

pierhead in 1900. At the same time, the fog signal building was moved

260 feet to a point 42 feet from the pierhead, and installed atop a

two-foot high timber foundation. A gallery and octagonal cast iron

lantern were then installed on the lakeward gable end of the fog signal

building, and the lantern outfitted with a new fixed red Sixth Order

Fresnel lens. To clear the new lantern, the fog whistle and deflector

were raised by 4 feet.

In 1914, the Army Corps of Engineers were again at Manistee

overseeing the erection of a breakwater on the south side of the harbor.

In concert with the elongated north pier, the two structures formed a

large stilling basin, ensuring calm water at the channel entrance. With

completion of the breakwater on April 6, 1914, a red steel skeleton

tower was established 80 feet from the outer end of the breakwater.

Equipped with an acetylene powered flashing red 300 mm lens standing 45

feet above the water, the 60-candlepower light was visible for 7 miles,

and the Manistee keepers once again found themselves responsible for

three lights and a first-class fog signal. With the availability of

municipal electricity, all three lights were electrified in 1925, with a

commensurate increase in both candlepower and visible range. In 1914, the Army Corps of Engineers were again at Manistee

overseeing the erection of a breakwater on the south side of the harbor.

In concert with the elongated north pier, the two structures formed a

large stilling basin, ensuring calm water at the channel entrance. With

completion of the breakwater on April 6, 1914, a red steel skeleton

tower was established 80 feet from the outer end of the breakwater.

Equipped with an acetylene powered flashing red 300 mm lens standing 45

feet above the water, the 60-candlepower light was visible for 7 miles,

and the Manistee keepers once again found themselves responsible for

three lights and a first-class fog signal. With the availability of

municipal electricity, all three lights were electrified in 1925, with a

commensurate increase in both candlepower and visible range.

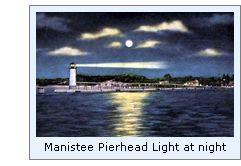

After major improvements to both the north and south piers in 1927,

the old fog signal building was removed, and replaced by a 39 foot-tall

iron tower on the outer end of the south pier. Capped with a decagonal

steel lantern outfitted with a Fifth Order Fresnel, the light was

equipped with a 5,000 candlepower incandescent electric bulb equipped

with a flashing mechanism which exhibiting a group occulting white light

with a period of 30 seconds. Sitting at a focal plane of 55 feet, the

new light was visible for a distance of 15 miles in clear weather

conditions. A single "Type C" diaphone powered by an electric

compressor was housed within the tower, and emitted a characteristic

similar to the light consisting of a group of three blasts every 30

seconds. With the erection of this new tower, the old wooden elevated

walk was torn down, and replaced by a cast iron walkway. After major improvements to both the north and south piers in 1927,

the old fog signal building was removed, and replaced by a 39 foot-tall

iron tower on the outer end of the south pier. Capped with a decagonal

steel lantern outfitted with a Fifth Order Fresnel, the light was

equipped with a 5,000 candlepower incandescent electric bulb equipped

with a flashing mechanism which exhibiting a group occulting white light

with a period of 30 seconds. Sitting at a focal plane of 55 feet, the

new light was visible for a distance of 15 miles in clear weather

conditions. A single "Type C" diaphone powered by an electric

compressor was housed within the tower, and emitted a characteristic

similar to the light consisting of a group of three blasts every 30

seconds. With the erection of this new tower, the old wooden elevated

walk was torn down, and replaced by a cast iron walkway.

The city of Manistee has done an incredible job of downtown

restoration, and has aptly earned the nickname of "Lake Michigan’s

Victorian Port City." The downtown shopping district has been

restored, and walkways along the river banks lead down to the lakeshore

where the 1927 north pierhead light and elevated walkway still stand

guard over the harbor entrance.

Keepers of this Light

Click Here to see

a complete listing of all Manistee Light keepers compiled by Phyllis L.

Tag of Great Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Seeing this Light

The weather was perfect at

Manistee. The sun burned-off the clouds, the breeze dropped to an almost

imperceptible level, and the lake laid-down flat as a billiard

table.

We walked the pier, and looked at the catwalk, which runs the entire

length of the pier.

We wondered at how rough the weather must get in the fall and spring to

require such a structure to be built. On a day such as this, it was difficult to think of this place as

anything other than a peaceful place to walk!

Finding this Light

From US31, take Memorial Drive West approximately one mile to the Lake.

Note that Memorial Drive changes to 5th Avenue along the way.

Contact

information

Manistee County Historical Museum

425 River Street

Manistee, MI 49660

(616) 723-5531

Reference Sources

Journals of the US Senate and

House of Representatives, various, 1851 - 1872

Annual report of the Fifth Auditor of the Treasury, 1838

History of Manistee county, Michigan, H.R. Page & Co.,

Chicago, 1882

History of the Great Lakes, J H Beers Co., 1899

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Board, various, 1852 - 1909

Annual reports of the Lake Carriers Association, various, 1914 -

1930

Around the Shores of Lake Michigan, Margaret Beattie Bogue, 1985

Personal observation at Manistee, 09/05/1998.

Keeper listings for this light appear courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|