|

Historical

Information

Lansing Shoals are located approximately 4 ˝ miles northeast of

Squaw Island, at the northern end of a narrow passage through which

vessels are forced to navigate on their trip between the Straits and the

northern harbors of Lake Michigan and Green Bay. Consisting of a number

of detached rocky strewn reefs with depths of less than 17 feet, the

reef long represented a significant threat to any vessel master

unfamiliar with the intricacies of the passage.

As traffic through the Straits burgeoned in the late 1890’s with

increasing ore shipments from Escanaba, mariners began lobbying the

Lighthouse Board to improve the lighting of the shoals. While the

construction of manned light stations in such locations was preferred,

the high costs associated with offshore construction made the anchoring

of lightships over such obstructions a significantly more expeditious

and cost effective solution. Without funding for a new vessel, the Board

was forced to review its existing inventory to identify if arrangements

could be made to allow the relocation of an existing vessel to mark

Lansing Shoals.

Lightship LV55 had been serving at Simmons Reef since October 24,

1891, and with a shift of traffic patterns to the south of White Shoal,

Simmons Reef had become less of a threat to mariners. Thus, the decision

was made to replace the LV55 with an acetylene gas buoy in 1899, thereby

freeing-up the lightship to be reassigned to duty on Lansing Shoal.

However, since the Simmons Reef lightship had been established by an Act

of Congress, the Board needed yet another Act to allow relocation of the

vessel, and thus the Board requested permission to make the change in

its annual report for 1899. A joint resolution of Congress approving the

relocation was made on May 3, 1900, and with the establishment of the

Simmons Reef Gas Buoy on July 19, 1900, LV55 was moved and anchored on

Lansing Shoals. Lightship LV55 had been serving at Simmons Reef since October 24,

1891, and with a shift of traffic patterns to the south of White Shoal,

Simmons Reef had become less of a threat to mariners. Thus, the decision

was made to replace the LV55 with an acetylene gas buoy in 1899, thereby

freeing-up the lightship to be reassigned to duty on Lansing Shoal.

However, since the Simmons Reef lightship had been established by an Act

of Congress, the Board needed yet another Act to allow relocation of the

vessel, and thus the Board requested permission to make the change in

its annual report for 1899. A joint resolution of Congress approving the

relocation was made on May 3, 1900, and with the establishment of the

Simmons Reef Gas Buoy on July 19, 1900, LV55 was moved and anchored on

Lansing Shoals.

LV55 was one of three identical light vessels authorized in a $60,000

appropriation on March 2, 1899. Built at the Blythe Craig Shipbuilding

Co at Toledo, Ohio, the three 103-foot oak-planked vessels were equipped

with a single screw driven by a small single cylinder steam engine.

These engines were designed to provide the vessels with sufficient power

to allow them to get on and off station under their own power. Thereby

eliminating the costs associated with having a lighthouse tender moving

them on and off station at the beginning and end of the navigation

season. Work on the vessels was completed on September 15, 1891, and on

delivery at the Detroit lighthouse depot they were officially designated

with hull numbers LV55, LV56 and LV57. The three vessels departed the

Lighthouse Depot under their own steam on October 19, and reaching Port

Huron that same evening, were met by the lighthouse tender DAHLIA, which

towed them north through Lake Huron and placed all three vessels on

their stations on October 24th, 1891.

Determined to affect a more permanent solution, the Board requested

an appropriation of $250,000 to construct a permanent light station on

Lansing Shoals in its annual report for 1908. However, with a tight

economy and numerous other projects underway, Congress repetitively

turned a deaf ear to the request. Thus, the venerable LV55 continued her

dedicated service over Lansing Shoals for the following twelve years,

until at her winter lay-up in Cheboygan in 1920 her hull was found to be

rotting beyond repair and she was declared "unseaworthy," and

removed from service. Thus, in 1920, the search was on for a replacement

vessel to serve at Lansing Shoal.

LV98 was built at the Racine-Truscott-Shell Lake Boat Company in

Muskegon in 1914. Built of steel in the "Whaleback style", her

overall length was 101', and she drew an impressive 23' 6".

Initially assigned to duty off Buffalo Harbor on June 12, 1915, she

served at that anchorage until she was transferred for relief service in

Lake Michigan in 1918. Deciding that assignment to Lansing Shoal was of

greater importance than continued service as a relief vessel, LV98 was

permanently reassigned to Lansing Shoal, taking up her new anchorage on

September 29, 1920. LV98 was built at the Racine-Truscott-Shell Lake Boat Company in

Muskegon in 1914. Built of steel in the "Whaleback style", her

overall length was 101', and she drew an impressive 23' 6".

Initially assigned to duty off Buffalo Harbor on June 12, 1915, she

served at that anchorage until she was transferred for relief service in

Lake Michigan in 1918. Deciding that assignment to Lansing Shoal was of

greater importance than continued service as a relief vessel, LV98 was

permanently reassigned to Lansing Shoal, taking up her new anchorage on

September 29, 1920.

Since the construction of the first 350-foot long lock at the Soo in

1855, the size of the locks had served as the limiting factor for the

length of commercial vessels able to move through them in and out of

Lake Superior. Since larger vessels allowed larger loads, while still

allowing for the same number of trips during the navigation season, ship

owners were constantly clamoring for the construction of larger locks at

the Soo, and a thirty year cycle of lock replacement began. With the

opening of the twin 850-foot long Davis and Sabin locks in 1919, vessels

quickly grew to previously unimagined dimensions, and the Army Corps of

Engineers was pressed to ensure that all navigation channels throughout

the lakes were improved to handle longer and deeper draft vessels.

The increased size and weight of these larger vessels allowed them to

break through thicker ice, and thus they were able to extend both ends

of the navigation season. However, largely as a result of her diminutive

size, LV98 was forced to wait for almost complete ice-out in the spring

before making her way out of winter quarters, and was likewise forced to

leave her station before the close of the navigation season in order to

avoid becoming trapped in the thickening ice. Thus, many vessels found

themselves navigating the area around Lansing Shoals without the benefit

of a light to guide the way, and the need for a permanent light station

on Lansing Shoal again became of critical necessity.

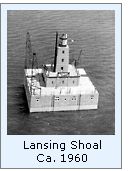

After receiving Congressional approval for the new station in 1926, a

site for the new Light was selected, and work on the new light began the

following year with the preparation of the lake bed with four feet of

stone to serve as a level foundation. Onto this foundation, four

rectangular concrete caissons, each 20 feet by 54 feet by 21 feet in

height were lowered to the bottom. The four caissons were placed with a

34-foot square open space at their center, and connected at the bottom

with ˝-inch rods, and the central space filled with a two-foot thick

slab of Portland cement. The self-unloader T W ROBINSON then arrived at

the site and filled the caissons and central space with stone.

The caissons were then capped with seven-foot thick slab of steel

reinforced concrete. Forms were then installed around the outer edge of

this slab, and 30-inch thick concrete walls poured, creating a 69-foot

square basement within the crib. Sub forms within the exterior walls

created openings for doors six feet above the water level on the north

and south sides, and 27 24" diameter porthole-style windows. Atop

the walls, a 12-inch thick slab of steel reinforced concrete was poured,

with central support provided by steel columns bolted to the basement

floor. This second slab sat 20 feet above lake level, and served as both

the main deck of the structure and as the ceiling for the basement

below. This basement was divided into two sections on opposite sides of

the crib, with one side serving as a machinery room and the other as

sleeping quarters for the crew. The caissons were then capped with seven-foot thick slab of steel

reinforced concrete. Forms were then installed around the outer edge of

this slab, and 30-inch thick concrete walls poured, creating a 69-foot

square basement within the crib. Sub forms within the exterior walls

created openings for doors six feet above the water level on the north

and south sides, and 27 24" diameter porthole-style windows. Atop

the walls, a 12-inch thick slab of steel reinforced concrete was poured,

with central support provided by steel columns bolted to the basement

floor. This second slab sat 20 feet above lake level, and served as both

the main deck of the structure and as the ceiling for the basement

below. This basement was divided into two sections on opposite sides of

the crib, with one side serving as a machinery room and the other as

sleeping quarters for the crew.

The machinery room housed a pair of diesel-powered electric

generators which were to supply power to the main light, radiobeacon and

general lighting throughout the structure. A small gasoline engine

powered generator served as a backup to the main generators in the case

of a failure with the main units. A pair of diesel-powered compressors

provided compressed air for the diaphone fog signal, two air-powered

derricks mounted on the northeast and northwest corners of the main

deck, and also provided pressure to the dwelling’s plumbing systems. A

coal storage bunker provided fuel for a hot water heating system,

connected to radiators throughout the dwelling. To both reduce noise and

fumes in the four bedrooms on the opposite side of the crib, the two

areas were separated by a ventilated hallway and the floor of the four

bedrooms stood sixteen inches above those in the equipment area. The machinery room housed a pair of diesel-powered electric

generators which were to supply power to the main light, radiobeacon and

general lighting throughout the structure. A small gasoline engine

powered generator served as a backup to the main generators in the case

of a failure with the main units. A pair of diesel-powered compressors

provided compressed air for the diaphone fog signal, two air-powered

derricks mounted on the northeast and northwest corners of the main

deck, and also provided pressure to the dwelling’s plumbing systems. A

coal storage bunker provided fuel for a hot water heating system,

connected to radiators throughout the dwelling. To both reduce noise and

fumes in the four bedrooms on the opposite side of the crib, the two

areas were separated by a ventilated hallway and the floor of the four

bedrooms stood sixteen inches above those in the equipment area.

Centered on the main deck above the basement, structural steel

framework was erected and sheathed with reinforced concrete walls

standing 37 feet square, with walls 12’ 8" high. As was the case

with the basement below, this main structure served double duty, housing

a large boat storage room, kitchen, dining room and living rooms for the

crew. Constructed in a similar manner to the main structure, the tower

rose three stories above the center of the flat roof of the main

structure, and stood 13-feet square at the base, with three stepped

sections tapering to 11 feet square below the gallery. A room

immediately below the lantern housed a Type F diaphone, with its

resonator protruding through the wall for maximum sound dispersion. Atop

the tower, a circular cast iron lantern was installed with helical

astragals, and outfitted with an occulting white Third Order Fresnel

lens illuminated by a 500-watt incandescent electric lamp. With a focal

plane of 69 feet, the lens was visible for a distance of 16 miles in

clear weather. Centered on the main deck above the basement, structural steel

framework was erected and sheathed with reinforced concrete walls

standing 37 feet square, with walls 12’ 8" high. As was the case

with the basement below, this main structure served double duty, housing

a large boat storage room, kitchen, dining room and living rooms for the

crew. Constructed in a similar manner to the main structure, the tower

rose three stories above the center of the flat roof of the main

structure, and stood 13-feet square at the base, with three stepped

sections tapering to 11 feet square below the gallery. A room

immediately below the lantern housed a Type F diaphone, with its

resonator protruding through the wall for maximum sound dispersion. Atop

the tower, a circular cast iron lantern was installed with helical

astragals, and outfitted with an occulting white Third Order Fresnel

lens illuminated by a 500-watt incandescent electric lamp. With a focal

plane of 69 feet, the lens was visible for a distance of 16 miles in

clear weather.

While there was still interior finish work remaining, and the

radiobeacon had yet to be installed, the new light was exhibited for the

first time on the night of October 6, 1928, and lightship LV98 was

removed from her anchorage and reassigned to Twelfth District relief

duty.

With completion of the interior trim work and the installation of the

200-watt radiobeacon the following spring, work at Lansing Shoal was

completed at a total cost of $262,000. The reinforced concrete

construction of the station made for an extremely strong structure,

which was put to the test during the great Armistice Day Storm of

November 11, 1940. With fierce northwestern gales blowing across the

lake, two freighters and a grain carrier were lost, and 70 storm-related

deaths recorded between Ludington and South Haven alone. During this

storm, winds of 126 miles per hour were recorded at Lansing Shoal, and

the station was coated with seven inches of ice, and most of the

porthole windows were blown out, causing the keepers to ride out the

storm in an inner room within the crib. With completion of the interior trim work and the installation of the

200-watt radiobeacon the following spring, work at Lansing Shoal was

completed at a total cost of $262,000. The reinforced concrete

construction of the station made for an extremely strong structure,

which was put to the test during the great Armistice Day Storm of

November 11, 1940. With fierce northwestern gales blowing across the

lake, two freighters and a grain carrier were lost, and 70 storm-related

deaths recorded between Ludington and South Haven alone. During this

storm, winds of 126 miles per hour were recorded at Lansing Shoal, and

the station was coated with seven inches of ice, and most of the

porthole windows were blown out, causing the keepers to ride out the

storm in an inner room within the crib.

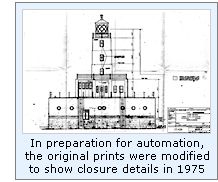

The Lansing Shoals Light was one of the last to be built on the Great

Lakes, and thus was one of the shortest lived. With advances in RADAR

and LORAN-C, through the sixties and seventies, such manned stations had

outlived their usefulness. The Coast Guard cutter Buckthorn arrived at

Lansing Shoal in the summer of 1976, and disassembled the Third Order

Fresnel, replacing the magnificent glass jewel with a diminutive

solar-powered 190 mm acrylic optic. After removing anything of value and

securing the station, the final crew was removed from the Light and

carried back to Station Charlevoix. At some point thereafter, all

windows in the station were sealed with brick and mortar, and the walls

sprayed with a coat of gunite , in order to reduce maintenance costs

and to help prevent vandalism. The Lansing Shoals Light was one of the last to be built on the Great

Lakes, and thus was one of the shortest lived. With advances in RADAR

and LORAN-C, through the sixties and seventies, such manned stations had

outlived their usefulness. The Coast Guard cutter Buckthorn arrived at

Lansing Shoal in the summer of 1976, and disassembled the Third Order

Fresnel, replacing the magnificent glass jewel with a diminutive

solar-powered 190 mm acrylic optic. After removing anything of value and

securing the station, the final crew was removed from the Light and

carried back to Station Charlevoix. At some point thereafter, all

windows in the station were sealed with brick and mortar, and the walls

sprayed with a coat of gunite , in order to reduce maintenance costs

and to help prevent vandalism.

In 1995, the 1,000-foot freighter INDIANA HARBOR passed too close to

the station, smashing into the crib, damaging some of the concrete of

the crib and smashing the metal corner protection on the station deck.

Amazingly, neither the light nor the vessel sustained major damage.

While no crews have tended the light in almost 30 years, Lansing

Shoal still beams her flashing white light fifteen miles across Lake

Michigan, warning mariners of the dangers lurking below the water. The

old Third Order Fresnel lens from the lighthouse was subsequently placed

on display at the Lansing State Museum, in Lansing.

Keepers of this Light

Click

Here

to see a complete listing of all Lansing Shoal Light

keepers compiled by Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Seeing this Light

We have yet to visit this light. We plan to visit in 2004, and will

report on our observations at that time. Thanks to Bernie and

Everett for honoring us with their photographs.

Finding this Light

This is an offshore light, and we are not

currently aware of any tours or charter boats that offer services to the

light. Thus, you will require your own seaworthy vessel to make the

trip.

Reference Sources

Annual reports of the Lighthouse

Board, various, 1891 - 1909

Annual reports of the Lake Carriers Association, various, 1901 -

1911

Great Lakes Light Lists, various, 1901 - 1997

Lightships and Lightship Stations of the United States Government,

Willard Flint, 1989

Holland's extremes of the century, Jim Pruitt. Holland Sentinel,

01/01/00

Northern Lights, Charles K. Hyde,

1995.

email from Bernard Hellstrom concerning 1995 collision, 01/02/00

The Long Ships Passing, Walter Havighurst,

1943

Keeper listings for this light appear

courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|