|

Historical

Information

Home to the Pottawatomie

tribe in the early part of the nineteenth century, the Kalamazoo River

wound its way among the scrub covered dunes before entering Lake

Michigan some seven miles to the south of Lake Macatawa and nineteen

miles to the north of the Black

River. William G. Butler and his family

became the first white settlers to enter the area when they and all

their worldly goods were lowered to a small boat from the deck of the

schooner MADISON, and rowed to shore in 1830. After living at the river

mouth for some time, Butler loaded his family onto a log raft and made

his way a couple of miles upstream to set up a homestead on a flat area

at the edge of a widening in the river.

Envisioning a growing community in the

area around his homestead, Butler platted the village that would

eventually become known as Saugatuck on July 17, 1834. Within a few

years a number of other settlers began moving in, setting up their own

homesteads and businesses. A sawmill was established at the northernmost

meander of the river about a mile from Saugatuck and three-quarters of a

mile from the river mouth, and a separate community known as Singapore

sprang up to support the mill. To provide assistance to vessels seeking

entry into the river, local business interests banded together to

establish a private light at the river mouth. Envisioning a growing community in the

area around his homestead, Butler platted the village that would

eventually become known as Saugatuck on July 17, 1834. Within a few

years a number of other settlers began moving in, setting up their own

homesteads and businesses. A sawmill was established at the northernmost

meander of the river about a mile from Saugatuck and three-quarters of a

mile from the river mouth, and a separate community known as Singapore

sprang up to support the mill. To provide assistance to vessels seeking

entry into the river, local business interests banded together to

establish a private light at the river mouth.

With the establishment of the first

school between Singapore and Saugatuck in 1836, Saugatuck was fast

becoming the thriving community that Butler had envisioned. Lumbering

and commercial activity gradually increased, and the Kalamazoo River

became busy with outbound log rafts and inbound vessels bringing

supplies to the growing communities upriver. Reacting to this increase

in maritime traffic, on January 25, 1836 Senator Linn presented a

petition before Congress on behalf of concerned maritime interests in

Detroit praying for harbor improvements and the construction of a

government lighthouse at the entrance to the Kalamazoo river.

Congress responded with an

appropriation of five thousand dollars for the construction of the

lighthouse on February 1, 1837. After the purchase of land to the north

of the river mouth from Horace M. Comstock on March 5, 1838 for the sum

of $250, a contract for the station's construction was awarded with the

stipulation that it be completed by October 15, 1838. However, during

his visit to the site on September 5thof that year, Lieutenant James T.

Homans reported that the contractor had made no progress beyond the

collection of a pile of stones for the building's foundation. While it

was normal practice at that time for the Collector of Customs of the

area to superintend such lighthouse construction projects, this had not

been the case at Kalamazoo River, and as a result the contractor had

been working without supervision to obvious deleterious results. Homans

appointed a special agent to superintend the construction, under whose

supervision the structure was completed the following year. The 30 foot

tall structure was constructed of rubble stone and was situated 75 feet

from the Lake Michigan shoreline at a point 14 feet above lake level. As

was the case with most lights built during the period, the tower was

capped with a birdcage-style lantern, housing an array of eleven Lewis

lamps with fourteen-inch reflectors. Payroll records for the station

indicate that keeper Stephen Nichols reported to his assignment on

November 11th, and it is thus likely that the Kalamazoo River Light was

exhibited for the first time late in the 1839 navigation season. Congress responded with an

appropriation of five thousand dollars for the construction of the

lighthouse on February 1, 1837. After the purchase of land to the north

of the river mouth from Horace M. Comstock on March 5, 1838 for the sum

of $250, a contract for the station's construction was awarded with the

stipulation that it be completed by October 15, 1838. However, during

his visit to the site on September 5thof that year, Lieutenant James T.

Homans reported that the contractor had made no progress beyond the

collection of a pile of stones for the building's foundation. While it

was normal practice at that time for the Collector of Customs of the

area to superintend such lighthouse construction projects, this had not

been the case at Kalamazoo River, and as a result the contractor had

been working without supervision to obvious deleterious results. Homans

appointed a special agent to superintend the construction, under whose

supervision the structure was completed the following year. The 30 foot

tall structure was constructed of rubble stone and was situated 75 feet

from the Lake Michigan shoreline at a point 14 feet above lake level. As

was the case with most lights built during the period, the tower was

capped with a birdcage-style lantern, housing an array of eleven Lewis

lamps with fourteen-inch reflectors. Payroll records for the station

indicate that keeper Stephen Nichols reported to his assignment on

November 11th, and it is thus likely that the Kalamazoo River Light was

exhibited for the first time late in the 1839 navigation season.

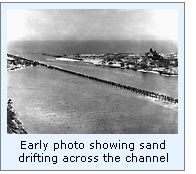

As the small amount of timber around

the river mouth was cut down, the fragile natural cover on the sand

dunes disappeared, and the dunes began to shift. This drifting began to

cause problems at the river mouth where sand frequently drifted across

the channel, requiring that it be removed to allow vessels with any

significant draft to gain entry. The drifting and blowing sand was also

evidently causing problems at the lighthouse in 1850 when Henry B.

Miller, the Inspector of Lights reported that the area on which the

station was built was wearing away quickly and the tower was in need of

whitewashing as a result of virtually constant sand-blasting. Concerned

that the erosion might undermine the integrity of the tower, Miller had

a timber protection constructed to help stem the erosion around the

building's foundation.

With the formation of the Lighthouse

Board in 1853, a plan was put in place to replace all of the Lewis lamps

in the system with the vastly superior French Fresnel lenses. As part of

this upgrade, a fixed white Sixth Order Fresnel lens was installed in

the Kalamazoo River light in 1856. Unabated, the problem with shifting

sands and erosion at the river mouth became a matter of such concern

that Senator Chandler presented a resolution on behalf of the Michigan

Legislature requesting Federal funds for improving the harbor on

February 11, 1858. Unfortunately, action was not taken quickly enough,

and the Kalamazoo River Light toppled from its foundation that same

year.

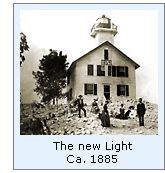

A work crew was dispatched to the

Kalamazoo River, and in an attempt to avoid the drifting and undermining

problems of the previous location, a site was chosen atop the dune 150

feet to the northeast of the site of the old light. By virtue of its

construction on sand, the new station was built on a foundation of three

hand-hewn 10" by 10" timbers which were bolted to the upper

end of nine 8-inch diameter cast iron pipe pilings driven into the sand

and encased in concrete and stone, and in an attempt to help stave-off

future erosion, the face of the dune was reinforced with slabs of

limestone barged-in from Alpena. The main structure was built to the

same plan as that used at Cheboygan the year before, and consisted of a

white painted two and a half story wooden frame structure with 8-inch

thick walls throughout, standing 25 foot by 40 foot in plan, topped by a

7 foot 9-inch square tower at the south gable end, extending fifteen

feet above the roof. The tower was capped with a gallery on which was

centered an octagonal cast iron lantern into which a new Fifth Order

Fresnel lens was installed. The tower stood 33 feet from its foundation

to the center of the lamp, providing the station with a focal plane of

45 feet above the surface of the lake. With the construction of a well

and a barn for the keepers horse, work was completed at the new station,

and the light was exhibited for the first time on an as yet undetermined

date in 1859. A work crew was dispatched to the

Kalamazoo River, and in an attempt to avoid the drifting and undermining

problems of the previous location, a site was chosen atop the dune 150

feet to the northeast of the site of the old light. By virtue of its

construction on sand, the new station was built on a foundation of three

hand-hewn 10" by 10" timbers which were bolted to the upper

end of nine 8-inch diameter cast iron pipe pilings driven into the sand

and encased in concrete and stone, and in an attempt to help stave-off

future erosion, the face of the dune was reinforced with slabs of

limestone barged-in from Alpena. The main structure was built to the

same plan as that used at Cheboygan the year before, and consisted of a

white painted two and a half story wooden frame structure with 8-inch

thick walls throughout, standing 25 foot by 40 foot in plan, topped by a

7 foot 9-inch square tower at the south gable end, extending fifteen

feet above the roof. The tower was capped with a gallery on which was

centered an octagonal cast iron lantern into which a new Fifth Order

Fresnel lens was installed. The tower stood 33 feet from its foundation

to the center of the lamp, providing the station with a focal plane of

45 feet above the surface of the lake. With the construction of a well

and a barn for the keepers horse, work was completed at the new station,

and the light was exhibited for the first time on an as yet undetermined

date in 1859.

While local business interests

constructed timber crib protections in an attempt to limit the effects

of drifting sand at the mouth of the river, Congress ignored frequent

pleas for Federal assistance to improve the river entrance. Finally, in

1869 Congress appropriated $30,000 for improvements at the Kalamazoo

River, and the War Department Engineers arrived to begin reconstruction.

A pair of timber crib protective piers filled with stone were

constructed on each side of the river mouth, which was widened to 225

feet, and the north pier was extended upriver an additional 450 feet to

provide protection for the dune on which the lighthouse was located. The

south pier revetments extended up the river almost three quarters of a

mile in order to maintain the navigable channel.

Congress appropriated an additional

$10,000 for harbor improvements at the river entrance in 1873, at which

time the piers were reinforced, and the North pier extended to a length

of 310 feet and the south pier to 225 feet in length. With the 1859

light now located some distance behind the piers, it was determined that

a light on one of the piers would better serve mariners seeking entry

into the river, and in 1876 the Fresnel lens was removed from the old

light and placed atop a white timber skeleton pierhead light at the end

of the south pier. Standing 27 feet tall, the new pierhead light had a

focal plane of 34 feet and was visible for a distance of 11½ miles at

sea. While the old light no longer functioned as an aid to navigation,

it continued to serve as the dwelling for keeper Samuel Underwood, who

was now forced to row across the river a number of times each day to

tend the new light. Congress appropriated an additional

$10,000 for harbor improvements at the river entrance in 1873, at which

time the piers were reinforced, and the North pier extended to a length

of 310 feet and the south pier to 225 feet in length. With the 1859

light now located some distance behind the piers, it was determined that

a light on one of the piers would better serve mariners seeking entry

into the river, and in 1876 the Fresnel lens was removed from the old

light and placed atop a white timber skeleton pierhead light at the end

of the south pier. Standing 27 feet tall, the new pierhead light had a

focal plane of 34 feet and was visible for a distance of 11½ miles at

sea. While the old light no longer functioned as an aid to navigation,

it continued to serve as the dwelling for keeper Samuel Underwood, who

was now forced to row across the river a number of times each day to

tend the new light.

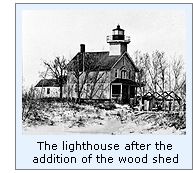

1883 saw the excavation of a 15-foot by

13½ -foot cellar beneath the keepers dwelling and the installation of

an underground cistern, located approximately 10 feet northwest of the

building. Downspouts attached to the gutters diverted rainwater from the

roof into the cistern to serve as a back-up water supply for the

dwelling. Wainscoting was installed around the building's foundation and

a wood shed and hand pump-operated drive well were added. Erosion in the

area of the keepers dwelling continued to cause concern in 1885, when

the dune was faced with logs to help stem the erosion. Three years

later, iron boat davits were installed at the pierhead light in order to

allow the keeper to lift the boat out of the water when servicing the

light. 1883 saw the excavation of a 15-foot by

13½ -foot cellar beneath the keepers dwelling and the installation of

an underground cistern, located approximately 10 feet northwest of the

building. Downspouts attached to the gutters diverted rainwater from the

roof into the cistern to serve as a back-up water supply for the

dwelling. Wainscoting was installed around the building's foundation and

a wood shed and hand pump-operated drive well were added. Erosion in the

area of the keepers dwelling continued to cause concern in 1885, when

the dune was faced with logs to help stem the erosion. Three years

later, iron boat davits were installed at the pierhead light in order to

allow the keeper to lift the boat out of the water when servicing the

light.

While making her way into the river in

1892, the steamer CHARLES MCVEA smashed head-on into the pierhead light.

The damage resulting was so severe that the light was considered

irreparably damaged, and the lens was returned to the lantern atop the

keepers dwelling and re-exhibited in its old home on the night of August

16. All salvageable materials from the pierhead light were removed and

carried across the river for storage in the station barn.

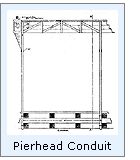

In the early 1890's, District Engineer

Major Milton B. Adams was experimenting with a "conduit"

system at a number of pierhead lights around Lake Michigan. Consisting

of a square wooden tube known as a conduit which extended along the pier

supported by trestles similar to those used to support elevated walks,

the conduit contained iron tracks on which a small wheeled cart holding

the lens was mounted. Connected by cable to pulleys at each end, it was

designed to allow the keepers to conduct all lens service close to

shore, then transporting the lens along the conduit to the end of the

pier where it was displayed from within a box with glass sides and a

galvanized iron roof. A 240 long conduit system was installed at the end

of an elevated walk on the south pier at Kalamazoo River in 1894, with

its fixed red lens lantern exhibited for the first time on the night of

May 23. However, with the exhibition of this new light, the old 1859

light was not extinguished, but continued to serve as a coast light. In the early 1890's, District Engineer

Major Milton B. Adams was experimenting with a "conduit"

system at a number of pierhead lights around Lake Michigan. Consisting

of a square wooden tube known as a conduit which extended along the pier

supported by trestles similar to those used to support elevated walks,

the conduit contained iron tracks on which a small wheeled cart holding

the lens was mounted. Connected by cable to pulleys at each end, it was

designed to allow the keepers to conduct all lens service close to

shore, then transporting the lens along the conduit to the end of the

pier where it was displayed from within a box with glass sides and a

galvanized iron roof. A 240 long conduit system was installed at the end

of an elevated walk on the south pier at Kalamazoo River in 1894, with

its fixed red lens lantern exhibited for the first time on the night of

May 23. However, with the exhibition of this new light, the old 1859

light was not extinguished, but continued to serve as a coast light.

1899 saw some welcome repairs and

additions at the main light. The structure was completely resided with

cut cedar shingles and a platform was constructed at the kitchen door. A

wooden walkway was built from this new platform to the verandah at the

front of the building, and a boathouse was constructed at the river

bank. A landing pier was built in front of the boathouse, and a 174 foot

long wooden walkway with hand rail was constructed from the boat landing

to the verandah.

While the conduit lights were heralded

by the District Engineer as being a major improvement when they were

first installed, in practice they proved to be less than reliable, and

were all subsequently dismantled. The Kalamazoo south pier conduit was

removed in 1900, and the light exhibited from a post located 152 feet

from the end of an elevated walk at a focal plane of 21 feet 6 inches.

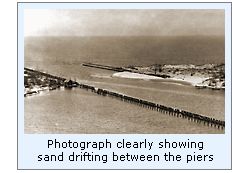

Drifting sand continued to plague the

river entrance at the dawn of the new century, and photographs taken at

the time frequently show sand drifting across the river from the

northern shore. After considerable contemplation it was decided that

rather than trying to keep the present river entrance sand free, it

would make greater sense to dig a new connecting channel between the

lake and the river approximately a mile further north along the lake

shore in the Singapore area. There were a number of reasons why this new

entrance was considered to be the optimal solution; The shore in that

area was considerably less susceptible to drifting, and thus the new

river entry could be maintained without the frequent digging and

dredging required of the old opening. An entry in the new location would

remove a major bend in the river, facilitating navigation to larger

vessels. The current was faster at this pint in the river, and would

thus help flush the silt and drifting sand into the lake. Finally, the

distance between the river entry and the towns upstream would be reduced

by over a mile, significantly reducing the time it would take to enter

or leave the upriver harbors after loading and unloading. Drifting sand continued to plague the

river entrance at the dawn of the new century, and photographs taken at

the time frequently show sand drifting across the river from the

northern shore. After considerable contemplation it was decided that

rather than trying to keep the present river entrance sand free, it

would make greater sense to dig a new connecting channel between the

lake and the river approximately a mile further north along the lake

shore in the Singapore area. There were a number of reasons why this new

entrance was considered to be the optimal solution; The shore in that

area was considerably less susceptible to drifting, and thus the new

river entry could be maintained without the frequent digging and

dredging required of the old opening. An entry in the new location would

remove a major bend in the river, facilitating navigation to larger

vessels. The current was faster at this pint in the river, and would

thus help flush the silt and drifting sand into the lake. Finally, the

distance between the river entry and the towns upstream would be reduced

by over a mile, significantly reducing the time it would take to enter

or leave the upriver harbors after loading and unloading.

Work on excavating the new channel

began in 1904, along with the construction of protective revetments on

each side of the opening and a pair of piers protruding into the lake to

help still the waters within the channel. On the completion of the new

channel in 1906, a simple post lamp with a platform for working on the

lens lantern was erected on the outer end of the new south pier, and

keeper George Baker who had been appointed to replace Samuel Underwood

after he was removed from the position in 1878, assumed responsibility

for both the new pierhead light and the old 1859 light, which now served

purely as a coast light, since it was located a mile south of the new

river entrance. To differentiate between the two lights, the pierhead

light at the new opening was officially named the Saugatuck Harbor South

Pierhead Light, while the old light continued to be known as the

Kalamazoo River Light. Work on excavating the new channel

began in 1904, along with the construction of protective revetments on

each side of the opening and a pair of piers protruding into the lake to

help still the waters within the channel. On the completion of the new

channel in 1906, a simple post lamp with a platform for working on the

lens lantern was erected on the outer end of the new south pier, and

keeper George Baker who had been appointed to replace Samuel Underwood

after he was removed from the position in 1878, assumed responsibility

for both the new pierhead light and the old 1859 light, which now served

purely as a coast light, since it was located a mile south of the new

river entrance. To differentiate between the two lights, the pierhead

light at the new opening was officially named the Saugatuck Harbor South

Pierhead Light, while the old light continued to be known as the

Kalamazoo River Light.

By 1909, without continued dredging,

the drifting sands completely filled the abandoned river entrance to the

south and people were able to walk directly between the piers where only

a few years previous large steamers had made their way in an out of the

river. 1909 was also an important year in the history of the Kalamazoo

Light as keeper George Baker retired after tending the light for 31

years. Baker was replaced by George Sheridan, who was transferred-in

after four years as First Assistant Keeper at the Michigan City Pierhead

Light. Sheridan was the first professional keeper to be assigned to the

Kalamazoo Light, all of those before him having been appointed directly

into their positions without prior lighthouse service and leaving the

service after their time at Kalamazoo. By 1909, without continued dredging,

the drifting sands completely filled the abandoned river entrance to the

south and people were able to walk directly between the piers where only

a few years previous large steamers had made their way in an out of the

river. 1909 was also an important year in the history of the Kalamazoo

Light as keeper George Baker retired after tending the light for 31

years. Baker was replaced by George Sheridan, who was transferred-in

after four years as First Assistant Keeper at the Michigan City Pierhead

Light. Sheridan was the first professional keeper to be assigned to the

Kalamazoo Light, all of those before him having been appointed directly

into their positions without prior lighthouse service and leaving the

service after their time at Kalamazoo.

Also in 1909, a concrete foundation was

poured on Saugatuck Harbor south entrance pier, and a square cast iron

pedestal and column, painted bright red to enhance their visibility were

installed atop the pedestal. The lower pedestal contained acetylene

storage tanks which supplied a 300 mm lens-lantern atop the 26 foot tall

structure. Equipped with an automatic sun valve, the light was designed

to operate for months without refilling or attendance, and its flashing

red 35-candlepower, emitting a single flash every three seconds, was

visible for a distance of 7 miles. Also in 1909, a concrete foundation was

poured on Saugatuck Harbor south entrance pier, and a square cast iron

pedestal and column, painted bright red to enhance their visibility were

installed atop the pedestal. The lower pedestal contained acetylene

storage tanks which supplied a 300 mm lens-lantern atop the 26 foot tall

structure. Equipped with an automatic sun valve, the light was designed

to operate for months without refilling or attendance, and its flashing

red 35-candlepower, emitting a single flash every three seconds, was

visible for a distance of 7 miles.

With the establishment of a flashing

white light on the Saugatuck Harbor north pier in 1914, the new river

entrance was completely illuminated, and the old 1859 light was

considered obsolete. George Sheridan exhibited the light of the

Kalamazoo River Light for the last time on the night of October 16, and

left to his new assignment at St. Joseph.

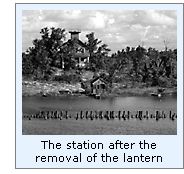

No longer serving any purpose, the

Lighthouse Service removed the lantern from atop the tower, and for the

next twenty years leased the old station buildings to Frederick F.

Fursman, the director of the famous Oxbow Summer School of Art, for the

sum of $10.00 a month. Only occupied during the summer months, the old

building began to suffer from vandalism and a lack of constant

maintenance. The building was offered-up for sale by closed mail bid in

1936, with the single bid received from Arthur F Deam, an architect and

a close friend of Fursman. The Deams took title to the building by

quitclaim deed on July 19, 1937, and over the following years used the

old building as a family summer cottage, undertaking an extensive

restoration of the station buildings and property. No longer serving any purpose, the

Lighthouse Service removed the lantern from atop the tower, and for the

next twenty years leased the old station buildings to Frederick F.

Fursman, the director of the famous Oxbow Summer School of Art, for the

sum of $10.00 a month. Only occupied during the summer months, the old

building began to suffer from vandalism and a lack of constant

maintenance. The building was offered-up for sale by closed mail bid in

1936, with the single bid received from Arthur F Deam, an architect and

a close friend of Fursman. The Deams took title to the building by

quitclaim deed on July 19, 1937, and over the following years used the

old building as a family summer cottage, undertaking an extensive

restoration of the station buildings and property.

The Kalamazoo Harbor South Pierhead

Light was electrified in the early 1950's and its output increased to

140 candlepower, also increasing its visible range to a distance of ten

miles. The light was also equipped with an electrically-operated

diaphragm fog signal, which emitted a two-second grunt every 15 seconds.

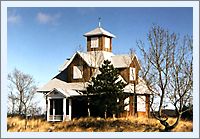

After years of loving restoration by

the Deam family, the old Kalamazoo Light station was obliterated by a

tornado on April 3 1956, leaving nothing intact beyond the cellar that

was dug beneath the lighthouse in 1883. The Deams managed to salvage a

number of articles from the old lighthouse, including porch railings,

six-paneled doors, some newel posts, one of the 10-inch by 10-inch beams

which had served as the main foundation for the old structure, and the

pediment displaying the construction date "1859" which was

displayed above the second floor windows of the old structure. Art Deam,

who had taken over as President of the Oxbow School on Fursman's death,

then set about designing a "lighthouse-style" summer home for

his family. In so doing, he carefully incorporated all of the salvaged

remnants of the beloved old structure into his new design, including the

"1859" pediment, which he proudly incorporated into the porch

above the front door entry.

Over the years since the new river

entrance had been cut, the stretch of river between the two river

entrances has become completely land-locked, with the section of river

becoming known as the Ox Bow lake. Almost one hundred years after the

old river entrance drifted shut, remnants of its original function can

still be seen. Two rows of pilings which once formed the revetments on

the north and south banks of the river still protrude above the surface

of Ox Bow lake, and the skeletal remains of the old piers can be seen

leading out towards the setting sun across Lake Michigan.

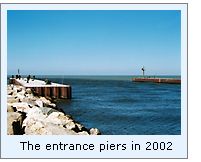

Late in the twentieth century, both

North and South Saugatuck Harbor Pierhead lights were replaced by white

"D9" cylindrical towers outfitted with modern acrylic optics.

The North Pierhead light displaying a horizontal black band across its

middle section, and the South Pierhead light showing a similar band of

red. The South Pierhead light still contains the grunting diaphragm fog

signal, and while few large commercial vessels still ply the waters of

the Kalamazoo River, Saugatuck is home port to a large fleet of private

yachts, power boats and charter fishing boats. Late in the twentieth century, both

North and South Saugatuck Harbor Pierhead lights were replaced by white

"D9" cylindrical towers outfitted with modern acrylic optics.

The North Pierhead light displaying a horizontal black band across its

middle section, and the South Pierhead light showing a similar band of

red. The South Pierhead light still contains the grunting diaphragm fog

signal, and while few large commercial vessels still ply the waters of

the Kalamazoo River, Saugatuck is home port to a large fleet of private

yachts, power boats and charter fishing boats.

Over the years, the shifting dunes have

completely removed all traces of the village of Singapore, and boaters

entering the harbor today are blissfully unaware that the luxury yacht

manufacturer on the north side of the channel sits atop the once

thriving lumbering community.

Keepers of this

Light

Click Here to see a complete listing of

all Kalamazoo River Light keepers compiled by Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes

Lighthouse Research.

Finding this Light

The old lighthouse is no

longer in existence, and thus cannot be seen. Please respect the privacy

of the owners of the "lighthouse cottage," and do not trespass

on their property.

Reference

Sources

Annual reports of the Fifth Auditor of the Treasury, various, 1835 -

1852

Annual reports of the lighthouse Board, various, 1853 - 1909

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Service, various, 1910 - 1939

Great Lakes Light Lists, various, 1861 - 1977

Annual reports of the Lake Carrier's Association, various, 1906 - 1940

Saugatuck Port Pilot, Great Lakes Cruising Club, 1944

Great Lakes Coast Pilots, 1958, 1961 and 2000.

Scott's New Coast Pilot, 1909

Saugatuck Through The Years, James S. Sheridan, 1982.

Photographs courtesy of Jeff Shook, Michigan Lighthouse

Conservancy.

Email correspondence with Jack Sheridan, Kit Lane & Norm Deam,

Jan & Feb 2002.

Historical photographs courtesy of the Sheridan, Deam and Peterson

collections.

Keeper listings for this light appear courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|