|

Historical

Information

Chicago of 1870 was in a

state of tremendous industrial growth, and with that growth a pall of

thick smoke from the industries around the city enveloped the foot of

the lake, making it increasingly difficult for mariners to locate the

harbor through the gloom. As part of ongoing harbor improvements, the

Army Corps of Engineers had extended the protective piers at the river

mouth to a length of over 2,000 feet, exacerbating the task of locating

the narrow channel between the piers.

Evaluating the situation in the spring of 1870, newly appointed

Eleventh Lighthouse District Engineer Brevet Brigadier General Orlando

M. Poe recommended the establishment of a coast light to the north of

the city to serve as a leading light to guide mariners towards the

harbor entrance. After conducting a survey of the area, the decision was

made to locate this new coast light on Grosse Point, a major promontory

which lay 13 miles to the north of the harbor, and Poe requested that

funding be provided for the station’s establishment in his annual

report for that year. Congress evidently concurred with the need for the

new light station, as it appropriated $35,000 for construction in March,

1871. Evaluating the situation in the spring of 1870, newly appointed

Eleventh Lighthouse District Engineer Brevet Brigadier General Orlando

M. Poe recommended the establishment of a coast light to the north of

the city to serve as a leading light to guide mariners towards the

harbor entrance. After conducting a survey of the area, the decision was

made to locate this new coast light on Grosse Point, a major promontory

which lay 13 miles to the north of the harbor, and Poe requested that

funding be provided for the station’s establishment in his annual

report for that year. Congress evidently concurred with the need for the

new light station, as it appropriated $35,000 for construction in March,

1871.

With funding in hand, Poe’s supervised the drafting of plans and

specifications for the new station at the Detroit depot, and bids for

furnishing the construction and iron work were opened on August 13,

1872. In accordance with Federal policy, the lowest bids were accepted,

and contracts were entered into with the appropriate parties

immediately. Work at Grosse Point began in September of 1872 with the

excavation for the foundations of the tower and dwelling. When weather

caused the end of work for the season in November, all of the stonework

had been completed to grade level and the necessary drainage tile

installed. Work at the site resumed in the beginning of May 1873, with

the driving of a tight cluster of 30-foot long oak piles into the earth

to serve as a base on which the tower’s concrete and stone foundation

would be laid. By the end of June, work on the exterior of the dwelling

and a 41-foot long covered way leading to the tower were virtually

complete, and plastering of the interior walls and ceilings was well

underway. Finding costs of construction to be greater than originally

projected, an additional $15,000 was appropriated on March 3, 1873.

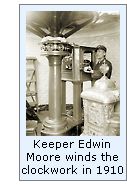

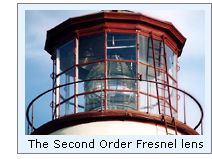

As work drew to a close towards the end of 1873, the double walled

Cream City brick tower stood 113 feet in height, with its 8-inch thick

cylindrical inner wall serving as a support for the 141-step cast iron

spiral stairway, which wound its way from ground level to the lantern

scuttle. The outer wall stood 22 feet in diameter at the foundation,

gracefully tapering to a diameter if 13 feet 3 inches at the cast iron

gallery, which was supported by 18 gracefully formed cast iron corbels.

A circular watch room was centered on the gallery, and topped by a

lantern with vertical astragals and outfitted with a huge Second Order

Fresnel lens. The lens was manufactured by the Henry-Lepaute Company of

Paris. Outfitted with a red flash panel, the lens rotated around a

three-wick lamp. Power for the rotating mechanism was provided by a

clockwork mechanism with a steel cable which was suspended within the

air space between the inner and outer tower walls. The clockwork was

carefully adjusted on a daily basis to ensure that the station’s

prescribed characteristic fixed white light with a red flash every 3

minutes. Work at the station continued through the winter of 1873 –

1874, with the station completed on March 1, 1874, in readiness for the

opening of the navigation season a few weeks later. As work drew to a close towards the end of 1873, the double walled

Cream City brick tower stood 113 feet in height, with its 8-inch thick

cylindrical inner wall serving as a support for the 141-step cast iron

spiral stairway, which wound its way from ground level to the lantern

scuttle. The outer wall stood 22 feet in diameter at the foundation,

gracefully tapering to a diameter if 13 feet 3 inches at the cast iron

gallery, which was supported by 18 gracefully formed cast iron corbels.

A circular watch room was centered on the gallery, and topped by a

lantern with vertical astragals and outfitted with a huge Second Order

Fresnel lens. The lens was manufactured by the Henry-Lepaute Company of

Paris. Outfitted with a red flash panel, the lens rotated around a

three-wick lamp. Power for the rotating mechanism was provided by a

clockwork mechanism with a steel cable which was suspended within the

air space between the inner and outer tower walls. The clockwork was

carefully adjusted on a daily basis to ensure that the station’s

prescribed characteristic fixed white light with a red flash every 3

minutes. Work at the station continued through the winter of 1873 –

1874, with the station completed on March 1, 1874, in readiness for the

opening of the navigation season a few weeks later.

The following year it was found that the sandy shoreline in front of

the station was eroding significantly, and $5,000 was requested to abate

the problem. With finding finally available in early 1875, two large

protective timber cribs were erected in front of the station in May. The following year it was found that the sandy shoreline in front of

the station was eroding significantly, and $5,000 was requested to abate

the problem. With finding finally available in early 1875, two large

protective timber cribs were erected in front of the station in May.

As a result of implementations throughout the lighthouse system, it

was determined that the establishment of a fog signal at Grosse Point

would serve as a valuable aid to maritime commerce during periods of fog

or thick weather. To this end, a pair of buildings, 15 by 12 feet and 20

by 12 feet were erected to the east of the tower in 1880. Standing 15

feet in height, both buildings were outfitted with identical horizontal

steam boilers piped to steam-operated sirens located on the lakeward

gable end. While only one of the signals would operate at any given

time, the second was available to serve as a back up in the event of

failure of the primary signal.

After the arrival of a work crew to replace the deteriorating water

supply line from th e Evanston municipal water works in 1882, the

following decade was relatively uneventful at Grosse Point, with only

routine maintenance and repairs recorded at the station. As witness to

the important role played by the station, the decision was made to

upgrade the fog signal apparatus to 10-inch locomotive-style team

whistles, whose blast was considerably louder than originally installed

sirens. Work on the north signal was completed and the new whistle

placed into operation on March 30, 1892, and the south signal activated

a month later on April 23. Prior to this time, lamp oil had been stored

in the service room which was incorporated in the covered way between

the dwelling and tower. In order to lessen the likelihood of fire

spreading throughout the station, the work crew also erected a

prefabricated circular iron oil storage building to the east of the

signal buildings. While the new steam whistles were a remarked

improvement over the smaller sirens, it took hours to get sufficient

steam raised within the boilers to activate them. To solve this problem,

water heaters were installed in 1898, allowing the keepers to build a

head of steam much more quickly, and thereby getting the whistles

screaming in less than an hour when conditions changed quickly. e Evanston municipal water works in 1882, the

following decade was relatively uneventful at Grosse Point, with only

routine maintenance and repairs recorded at the station. As witness to

the important role played by the station, the decision was made to

upgrade the fog signal apparatus to 10-inch locomotive-style team

whistles, whose blast was considerably louder than originally installed

sirens. Work on the north signal was completed and the new whistle

placed into operation on March 30, 1892, and the south signal activated

a month later on April 23. Prior to this time, lamp oil had been stored

in the service room which was incorporated in the covered way between

the dwelling and tower. In order to lessen the likelihood of fire

spreading throughout the station, the work crew also erected a

prefabricated circular iron oil storage building to the east of the

signal buildings. While the new steam whistles were a remarked

improvement over the smaller sirens, it took hours to get sufficient

steam raised within the boilers to activate them. To solve this problem,

water heaters were installed in 1898, allowing the keepers to build a

head of steam much more quickly, and thereby getting the whistles

screaming in less than an hour when conditions changed quickly.

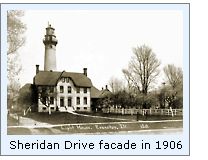

1900 was a busy year at Grosse Point, with a work crew arriving to

erect an iron fence an gate on the Sheridan Drive property line and

building a second oil house of brick, standing 8 feet by 10 feet and 12

feet in height. The work crew also raised a flag pole and poured

concrete walks connecting the front doors of the duplex dwelling to the

new Sheridan drive gate. 1900 was a busy year at Grosse Point, with a work crew arriving to

erect an iron fence an gate on the Sheridan Drive property line and

building a second oil house of brick, standing 8 feet by 10 feet and 12

feet in height. The work crew also raised a flag pole and poured

concrete walks connecting the front doors of the duplex dwelling to the

new Sheridan drive gate.

By the turn of the twentieth century, the area around the light

station had undergone a metamorphosis. At the time of the station’s

establishment 30 years earlier, the area was somewhat open, with but few

houses scattered around the area. With Chicago’s commercial success

and expansion, an increasing number of moneyed businessmen had built

mansions along the lakeshore around the light station in order to escape

the turmoil of the big city. A conflict between the need to sound the

fog signals and the peace and quiet desired by the areas gentry was

inevitable. Learning from previous experiments undertaken in Duluth in

1895 and Marquette in 1897, the Lighthouse Board installed reflectors

behind the whistles in 1901. Built on a framework of pine and sheathed

in iron, the reflectors were packed with sawdust to simultaneously

absorb sound landward, while successfully deflecting the majority of the

sound to sea. With a semblance of peace restored to the area, life again

settled into a relatively uneventful ten year period at the station. The

boat landing was re-planked in 1904, the north fog signal building

remodeled in 1905, and the illumination apparatus in the light was

upgraded from the triple wick kerosene lamp to an incandescent oil vapor

system in 1910 with an increase in output to 10,000 candlepower for the

fixed white light and 32,000 candlepower for the red flash.

Evidently the Cream City brick used in building the Grosse Point

tower was of an inferior consistency, as Twelfth District Inspector

Lewis M. Stoddard noted the deteriorating condition of the brick during

his inspection of the station in 1913. While similar conditions had been

rectified with the installation steel casings over the brick at Big

Sable Point in 1900 and at Cana Island in 1902, Stoddard proposed a less

expensive remedy at Grosse Point. The following Spring, a work crew from

the General Cement Gun Company arrived at the station, and after erecting a wooden scaffolding around

the tower, applied a protective coating of cement to the entire tower

exterior from ground to gallery. The work was completed on May 20 at a

total cost of only $2,678.52. Evidently the Cream City brick used in building the Grosse Point

tower was of an inferior consistency, as Twelfth District Inspector

Lewis M. Stoddard noted the deteriorating condition of the brick during

his inspection of the station in 1913. While similar conditions had been

rectified with the installation steel casings over the brick at Big

Sable Point in 1900 and at Cana Island in 1902, Stoddard proposed a less

expensive remedy at Grosse Point. The following Spring, a work crew from

the General Cement Gun Company arrived at the station, and after erecting a wooden scaffolding around

the tower, applied a protective coating of cement to the entire tower

exterior from ground to gallery. The work was completed on May 20 at a

total cost of only $2,678.52.

In 1935, the decision was made to automate the station, and a work

crew was dispatched to Grosse Point to undertake the work. Electricity

from the municipal utility was brought to the building, and the light

automated with the installation of an incandescent electric bulb with

automatic twin bulb changer. As part of this new installation, the lamp

was also outfitted with an automatic flash mechanism and the

characteristic of the light changed to exhibit a pair of 68,000

candlepower white flashes every 15 seconds. While the automation work

crew was on site, a large gap was found between the Assistant keeper’s

wing and the main dwelling. With the station’s automation eliminating

the need for live-in keepers, the decision was made to demolish both

this wing and the covered way connecting the tower and dwelling. In 1935, the decision was made to automate the station, and a work

crew was dispatched to Grosse Point to undertake the work. Electricity

from the municipal utility was brought to the building, and the light

automated with the installation of an incandescent electric bulb with

automatic twin bulb changer. As part of this new installation, the lamp

was also outfitted with an automatic flash mechanism and the

characteristic of the light changed to exhibit a pair of 68,000

candlepower white flashes every 15 seconds. While the automation work

crew was on site, a large gap was found between the Assistant keeper’s

wing and the main dwelling. With the station’s automation eliminating

the need for live-in keepers, the decision was made to demolish both

this wing and the covered way connecting the tower and dwelling.

After the placement of the Grosse Point Outer Lighted Bell Buoy

offshore in 1939, it became clear that the Grosse Point light was

rendered obsolete, and the station was decommissioned in 1941 and turned

over to the City of Evanston. The building sat empty until 1944, when

the tower was used by two physicists from Northwest University to

conduct experiments in the us of infrared transmission as a form of

enhanced radar. After creation of the historic Lighthouse Park District,

the City of Evanston managed to obtain permission to have the light

reestablished as a private aid to navigation in 1946. After the placement of the Grosse Point Outer Lighted Bell Buoy

offshore in 1939, it became clear that the Grosse Point light was

rendered obsolete, and the station was decommissioned in 1941 and turned

over to the City of Evanston. The building sat empty until 1944, when

the tower was used by two physicists from Northwest University to

conduct experiments in the us of infrared transmission as a form of

enhanced radar. After creation of the historic Lighthouse Park District,

the City of Evanston managed to obtain permission to have the light

reestablished as a private aid to navigation in 1946.

With Evanston’s

conversion of the station into a museum, a major $100,000 improvement

project was undertaken during the early 1990’s to restore the

buildings to their turn of the century appearance. To this end, the

Assistant’s wing and covered way which had been removed during the

station’s automation in 1935 were both reconstructed to allow full

interpretation of the station during the height of its operation. The

majestic light station continues to serve as a museum, and is open to

the public for a small admission fee during limited hours during the

summer months.

Keepers of this

Light

Click Here to see a complete listing of

all Grosse Point Light keepers compiled by Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes

Lighthouse Research.

Seeing this

Light

Directions will be forthcoming after we visit this light in the Spring of

2001.

Contact information

Lighthouse Park District

2601 Sheridan Road

Evanston, IL 60201-1752

Telephone: 847.328.6961

Website: www.grossepointlighthouse.org

Email:lpdnhl@grossepointlighthouse.org

Reference Sources

Annual reports of the

Lighthouse Board, various, 1871 – 1909

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Service, various, 1910 – 1929

Annual reports of the Lake Carriers Association, 1903 – 1939

Great Lakes Light Lists, various, 1873 - 1999

Lewis M. Stoddard note book, Michigan Lighthouse Conservancy

collection

Statutes at Large, 42nd Congress, 3rd Session , March 3,

1873

Grosse Point Light Station - National Historic Landmark Study - by

Donald J. Terras

The Keeper’s Log, United States Lighthouse Society, Fall 1993

Keeper listings for this light

appear courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|