|

Historical

Information

Grays Reef Passage serves as

the primary route between the Straits and the ports on the southern

shores of Lake Michigan. Bounded on the east by Vienna Shoal and East

Shoal, Grays Reef itself forms the western boundary of the passage, and

consists of an extensive area of shallow water over a rocky bottom

stretching over eight miles in length. With some portions of its rocky

bottom almost protruding above the water’s surface, the reef has long

represented a significant threat to any vessel master unfamiliar with

the intricacies of the passage.

As traffic

through the Straits burgeoned with increasing shipments of iron ore out

of Lake Superior through the 1880’s, mariners began lobbying the

Lighthouse Board to improve the lighting of a number of dangerous shoals

in the Straits area. While the construction of manned light stations in

such locations was preferred, the high costs associated with offshore

construction made the anchoring of lightships over such obstructions a

significantly more expeditious and cost effective solution. Responding

to this need, the Lighthouse Board requested Congressional funding for

the construction of three such vessels in the late 1880’s for

deployment on White Shoal, Simmons Reef and Grays Reef. As traffic

through the Straits burgeoned with increasing shipments of iron ore out

of Lake Superior through the 1880’s, mariners began lobbying the

Lighthouse Board to improve the lighting of a number of dangerous shoals

in the Straits area. While the construction of manned light stations in

such locations was preferred, the high costs associated with offshore

construction made the anchoring of lightships over such obstructions a

significantly more expeditious and cost effective solution. Responding

to this need, the Lighthouse Board requested Congressional funding for

the construction of three such vessels in the late 1880’s for

deployment on White Shoal, Simmons Reef and Grays Reef.

Congress responded on March 2, 1899 with an appropriation of $60,000.

The Board submitted requests for quotation to a number of shipbuilders,

with the contract ultimately awarded to the Blythe Craig Shipbuilding Co

of Toledo, Ohio. Plans for the three identical 103-foot oak-planked

vessels called for them to be equipped with a single screw driven by a

small single cylinder steam engine. These engines were designed to

provide the vessels with sufficient power to allow them to get on and

off station under their own power. Thereby eliminating the costs

associated with having a lighthouse tender moving them on and off

station at the beginning and end of the navigation season.

Work on the

vessels was completed on September 15, 1891, and on delivery at the

Detroit lighthouse depot they were officially designated with hull

numbers LV55, LV56 and LV57. The three vessels departed the Lighthouse

Depot under their own steam on October 19, and reaching Port Huron that

same evening, were met by the lighthouse tender DAHLIA, which towed them

north through Lake Huron and placed all three vessels on their stations

on October 24th ,1891. Work on the

vessels was completed on September 15, 1891, and on delivery at the

Detroit lighthouse depot they were officially designated with hull

numbers LV55, LV56 and LV57. The three vessels departed the Lighthouse

Depot under their own steam on October 19, and reaching Port Huron that

same evening, were met by the lighthouse tender DAHLIA, which towed them

north through Lake Huron and placed all three vessels on their stations

on October 24th ,1891.

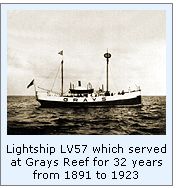

With the exception of spending winters in Cheboygan Harbor, where she

underwent annual maintenance during the annual ice-over, LV57 served on

Grays Reef every shipping season for the following thirty-two years

until her hull was found to be rotted beyond repair at winter lay-up in

1923, and she was immediately removed from service.

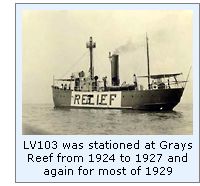

To replace the

retiring vessel, LV103 was temporarily placed in Grays Reef at the

opening of the 1924 navigation season. Built by the Consolidated

Shipbuilding Corporation of Morris Heights New York, LV103 had been

delivered to the District headquarters in Milwaukee on June, 1921, and

had spent the past three years serving as a relief vessel throughout

Lake Michigan. To replace the

retiring vessel, LV103 was temporarily placed in Grays Reef at the

opening of the 1924 navigation season. Built by the Consolidated

Shipbuilding Corporation of Morris Heights New York, LV103 had been

delivered to the District headquarters in Milwaukee on June, 1921, and

had spent the past three years serving as a relief vessel throughout

Lake Michigan.

LV103 remained

at Grays Reef until 1927, when LV56 was transferred-in on the opening of

the navigation season. One of the two sister ships to LV56, from all

appearances she had weathered the rigors of work on the lake better than

her sister, and was still considered to be in serviceable condition.

After commissioning in 1891, she had served at White Shoal until 1909,

when she was reassigned to North Manitou Shoal after completion of

construction of the White Shoal Light. However, the outward appearances

of her seaworthiness were evidently misleading, as she too was found to

be suffering from a considerable amount of hull deterioration, and was

declared unseaworthy during her 1928-1929 winter lay-up in Cheboygan,

and she too was removed from service. LV103 remained

at Grays Reef until 1927, when LV56 was transferred-in on the opening of

the navigation season. One of the two sister ships to LV56, from all

appearances she had weathered the rigors of work on the lake better than

her sister, and was still considered to be in serviceable condition.

After commissioning in 1891, she had served at White Shoal until 1909,

when she was reassigned to North Manitou Shoal after completion of

construction of the White Shoal Light. However, the outward appearances

of her seaworthiness were evidently misleading, as she too was found to

be suffering from a considerable amount of hull deterioration, and was

declared unseaworthy during her 1928-1929 winter lay-up in Cheboygan,

and she too was removed from service.

With

construction of the new light at Poe Reef well underway, plans were put

in place to relocate LV99 from Poe to Grays Reef upon the light station’s

completion the following summer. Thus relief vessel LV103 was once again

temporarily stationed at Grays Reef at the beginning of the 1929

shipping season until she was replaced by LV99 that fall. LV99 was one

of the newest of the Great Lakes lightships, and represented the current

state of the art. Built in 1920 by Rice Brothers at Boothbay Harbor in

Maine, she was steel-hulled, 92-feet in length, and was equipped with a

single acetylene powered light, a ten-inch steam fog whistle and a

submarine bell, which had been added to her arsenal of warning equipment

in 1923. With

construction of the new light at Poe Reef well underway, plans were put

in place to relocate LV99 from Poe to Grays Reef upon the light station’s

completion the following summer. Thus relief vessel LV103 was once again

temporarily stationed at Grays Reef at the beginning of the 1929

shipping season until she was replaced by LV99 that fall. LV99 was one

of the newest of the Great Lakes lightships, and represented the current

state of the art. Built in 1920 by Rice Brothers at Boothbay Harbor in

Maine, she was steel-hulled, 92-feet in length, and was equipped with a

single acetylene powered light, a ten-inch steam fog whistle and a

submarine bell, which had been added to her arsenal of warning equipment

in 1923.

Since the construction of the first 350-foot long lock at the Soo in

1855, the size of the locks had served as the limiting factor for the

length of commercial vessels able to move through them in and out of

Lake Superior. Since larger vessels allowed larger loads, while still

allowing for the same number of trips during the navigation season, ship

owners were constantly clamoring for the construction of larger locks at

the Soo, and a thirty year cycle of lock replacement began. With the

opening of the twin 850-foot long Davis and Sabin locks in 1919, vessels

quickly grew to previously unimagined dimensions, and the Army Corps of

Engineers was pressed to ensure that all navigation channels throughout

the lakes were improved to handle longer and deeper draft vessels.

With many of the largest ore-carrying vessels making their way

through Grays Reef Passage on their down-bound trip to the steel mills

of southern Lake Michigan, the US Army Corps of Engineers were working

in the Passage in the early 1930’s taking soundings in preparation to

enlarging the two mile long passage to a width of 3,000 feet and a

minimum depth of 25 feet, opening it up to the largest vessels of the

time.

As a result of improvements in offshore construction learned in the

construction of the Lake Huron stations at Poe Reef, Martin Reef and

Fourteen foot Shoal in the late 1920’s, the technology was in place

and the time was right to finally replace the lightship on Grays Reef

with a first class light station to guide mariners through the passage.

After consulting with the Army Corps of Engineers and the Lake Carrier’s

Association, the Lighthouse Service determined that the optimum location

for the new station would be in 26 feet of water, 100 feet off a turn in

the proposed channel, and slightly to the southeast of the existing

lightship anchorage.

Funding for the new station was approved by Congress on February 14,

1934, and plans and specifications were drawn up soon thereafter. The

design of the steel lighthouse structure was a modification and

enlargement of the F. P. Dillon and W. G. Will design being used for breakwater

lights at Conneaut and Huron, and was an exact twin a new station to be

established at Minneapolis Shoal. Bids for construction were advertised

with a stipulated completion date of by July 1, 1936. The contract for

the station’s construction was finally awarded to the Greiling

Brothers Company, who had considerable experience in water-based

construction including the erection of the breakwaters at Ludington and

a large dock at Rogers City. Funding for the new station was approved by Congress on February 14,

1934, and plans and specifications were drawn up soon thereafter. The

design of the steel lighthouse structure was a modification and

enlargement of the F. P. Dillon and W. G. Will design being used for breakwater

lights at Conneaut and Huron, and was an exact twin a new station to be

established at Minneapolis Shoal. Bids for construction were advertised

with a stipulated completion date of by July 1, 1936. The contract for

the station’s construction was finally awarded to the Greiling

Brothers Company, who had considerable experience in water-based

construction including the erection of the breakwaters at Ludington and

a large dock at Rogers City.

Under the supervision of Chester Greiling, work began on shore at St.

Ignace in the summer of 1934 with the construction of a 65-foot square

timber crib, which would form a foundation for the concrete pier on

which the station would be erected. Built of 12" by 12"

timbers, internal cross-timbers divided the inner section of the crib

into 49 pockets. On completion of the crib in September, it was

carefully floated and towed out of St. Ignace and west through the

Straits. Arriving at Grays Reef, the crib was centered on the selected

site, and the 25 inner pockets slowly filled with stone. Eventually

overcoming its natural buoyancy, the crib sank in place on the bottom.

The 25 outer pockets were then filled with concrete, and forms erected

for the pouring of a six-foot thick concrete floor and walls. Work

continued through the fall of 1934 until the onset of winter made

conditions too dangerous, and work was ended until the opening of the

1935 navigation season

By June 1935, the temporary stone had been removed from the center

pockets and refilled with concrete. Forms were installed, spanning

across the walls and a steel reinforced concrete floor, one foot thick

poured to create the pier deck. The center section of the pier between

the six-foot thick walls was left open to form two-story mechanical

room. The lighthouse building itself was to stand 30-feet square and 15

feet tall, and consisted of a structural steel girder framework over

which walls of sheet steel were to be riveted in place. Much of the

steel framework was pre-assembled in St. Ignace and loaded on the

Greiling boat RAMBLER, and then hoisted onto the pier at the reef for

erection. By the end of 1935, work on the concrete pier and steel

framework was both complete, when the work was again suspended with the

arrival of winter By June 1935, the temporary stone had been removed from the center

pockets and refilled with concrete. Forms were installed, spanning

across the walls and a steel reinforced concrete floor, one foot thick

poured to create the pier deck. The center section of the pier between

the six-foot thick walls was left open to form two-story mechanical

room. The lighthouse building itself was to stand 30-feet square and 15

feet tall, and consisted of a structural steel girder framework over

which walls of sheet steel were to be riveted in place. Much of the

steel framework was pre-assembled in St. Ignace and loaded on the

Greiling boat RAMBLER, and then hoisted onto the pier at the reef for

erection. By the end of 1935, work on the concrete pier and steel

framework was both complete, when the work was again suspended with the

arrival of winter

With the arrival of Greiling and his crew in 1936, the skinning of

the main building and tower was underway, and the inner walls lined with

concrete block to both prevent condensation and provide insulation for

the living quarters within. The mechanical room in the cellar extended

up into the first floor of the building, and housed diesel powered

generators to provide electrical power for the light and dwelling,

compressors to power the Type F diaphone fog signal, and boilers for the

hot water central heating system. The second floor made up the keepers

quarters, and was replete with electric lighting and sanitary plumbing.

Centered atop the main building, the 17-foot tall tower stood 16-feet

square at the base, and after a graceful rolled flare, narrowed to

10-feet square beneath the gallery.

The tower was topped by a circular lantern with helical astragals,

and outfitted with an occulting red Third and a Half Order Fresnel lens.

Illuminated by a 13,000 candlepower incandescent electric bulb, the bulb

was outfitted with an automatic flasher mechanism with caused it to

exhibit a repeated characteristic 4 seconds of light followed by 2

seconds of darkness. Seated at a focal plane of 82 feet, the light was

visible for a distance of 17 miles in clear weather conditions. The tower was topped by a circular lantern with helical astragals,

and outfitted with an occulting red Third and a Half Order Fresnel lens.

Illuminated by a 13,000 candlepower incandescent electric bulb, the bulb

was outfitted with an automatic flasher mechanism with caused it to

exhibit a repeated characteristic 4 seconds of light followed by 2

seconds of darkness. Seated at a focal plane of 82 feet, the light was

visible for a distance of 17 miles in clear weather conditions.

Greiling finished work on the station in September of 1936, two

months behind the stipulated date, and considerably over budget. With

the activation of the new light, LV99 was removed from her anchorage,

the last in a long line of stalwart lightships to serve mariners in Lake

Michigan’s treacherous northern waters.

On May 3, 1937, a radio beacons was installed at the station, and its

signal exactly synchronized with the diaphone fog signal. This

synchronization allowed mariners to precisely calculate their distance

from the station by measuring the time differential between receiving

the radio signal and hearing the diaphone. With responsibility for the

nation’s aids to navigation transferred to the Coast Guard in 1939,

Coast Guard crews began manning the station as the civilian Lighthouse

Service keepers retired. On May 3, 1937, a radio beacons was installed at the station, and its

signal exactly synchronized with the diaphone fog signal. This

synchronization allowed mariners to precisely calculate their distance

from the station by measuring the time differential between receiving

the radio signal and hearing the diaphone. With responsibility for the

nation’s aids to navigation transferred to the Coast Guard in 1939,

Coast Guard crews began manning the station as the civilian Lighthouse

Service keepers retired.

Advances in solar-powered systems in the 1970’s facilitated the

automation of an increasing number of offshore lights, and the

elimination of the high costs associated with keeping five-man crews

supplied throughout the navigation season. Thus, in 1976 the lights at

White Shoal, Lansing Shoal and Grays Reef were all automated, and the

last crew to serve at the Grays Reef was removed.

Today, Grays Reef’s light is provided by a 190 mm 12-volt dc

solar-powered acrylic Tidelands Signal optic. Power generated by the

photovoltaic panel during daylight hours is stored in a series of

batteries for use at night, when the stations flashing red light still

shines 15 miles across the lake to warn mariners of the western limit of

the passage.

The station now sits empty with the exception of infrequent visits by

Coast Guard crews to conduct standard maintenance on the lighting

system. The station is also "manned" for a couple of days

every July, when with the permission of the Coast Guard, officials of

the Chicago Yacht club use the station as an observation platform to

monitor contestants making their way through Grays Reef passage during

the annual Chicago to Mackinac yacht race.

Keepers of this Light

Click

Here to see a complete listing of all Grays Reef Light keepers

compiled by Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Seeing this Light

Sheplers Ferry Service out of Mackinaw City

offers a number of lighthouse cruises during the summer season. Their

"Westward Tour" includes passes by White Shoal, Grays Reef,

Waugoshance and St. Helena Island. For schedules and rates for this

tour, visit their website at: www.sheplerswww.com

or contact them at:

PO Box 250

Mackinaw City, MI 49701

Phone (800) 828-6157

Reference Sources

Annual reports of the Lighthouse

Board, various, 1869 – 1910

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Service, 1911 – 1938

Great Lakes Light Lists, various, 1939 – 1977

Grays Grief, Michigan History magazine, Saralee R. Howard-Filler,

Sept/Oct 1986

Last Lakes lighthouse crew departs, Detroit News, October 7, 1976

Great Lakes Lightships – Shoal Assignments, Terry Pepper, 2000

Great Lakes Pilot, US Army Corps of Engineers, 1958

Annual reports of the Great Lakes Carriers Association, various,

1914 - 1937

Lightships and Lightship Stations of the United States Government,

Willard Flint, 1989

The Long Ships Passing, Walter Havighurst,

1943

Keeper listings for this light appear courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|