|

Historical Information

At the middle of the nineteenth century, the curving hook of Ottawa

Point had long formed a natural shelter for Tawas Bay, and was

frequently used as a harbor of refuge for vessels escaping squalls out

on Lake Huron. With the end of the Point difficult to discern at night

or in inclement weather, a grass-roots lobbying campaign pleaded to

Stephen Pleasonton, the Fifth Auditor of the Treasury, for the erection

of a lighthouse to guide vessels past Ottawa Point and into Tawas Bay.

Apparently Pleasonton looked upon the project with favor, as on his

recommendation, Congress appropriated $5,000 for the construction of a

Light on Ottawa Point in September 28, 1850.

Construction at the Point began early

in 1852, and continued through the remainder of the summer and into the

fall. Since no photograph of this early tower have surfaced, it's exact

appearance is uncertain. However, we do know that the tower walls were

built of solid rubble stone masonry, and stood 45 feet in height from

grade level to the center of an array of Lewis lamps equipped with

silvered reflectors. By virtue of the tower's construction on elevated

ground, the Light sat at a focal plane of 54 feet above lake level and

approximately twenty feet from the diminutive 1½-story brick Keeper's

dwelling. Construction came to a close in October 1852, and with the

work completed so late in the year, the decision was made not to exhibit

the light until the following spring. Sherman Wheeler was appointed as

the station's first Keeper, and arriving at Ottawa Point late that

winter, exhibited the new Light for the first on the opening of the 1853

season of navigation. The tower and dwelling were the first permanent

structures to be built on Tawas Bay, with log cabins being the only

other structures in the area. Construction at the Point began early

in 1852, and continued through the remainder of the summer and into the

fall. Since no photograph of this early tower have surfaced, it's exact

appearance is uncertain. However, we do know that the tower walls were

built of solid rubble stone masonry, and stood 45 feet in height from

grade level to the center of an array of Lewis lamps equipped with

silvered reflectors. By virtue of the tower's construction on elevated

ground, the Light sat at a focal plane of 54 feet above lake level and

approximately twenty feet from the diminutive 1½-story brick Keeper's

dwelling. Construction came to a close in October 1852, and with the

work completed so late in the year, the decision was made not to exhibit

the light until the following spring. Sherman Wheeler was appointed as

the station's first Keeper, and arriving at Ottawa Point late that

winter, exhibited the new Light for the first on the opening of the 1853

season of navigation. The tower and dwelling were the first permanent

structures to be built on Tawas Bay, with log cabins being the only

other structures in the area.

In the early 1850's a cry arose in the

maritime community, voicing concern over Pleasonton's tight-fisted

administration of the nation's aids to navigation. A clerical

administrator, Pleasonton had no maritime experience, and it showed-up

in the sub standard workmanship and poorly chosen locations of many of

the lighthouses erected under his administration. A study commissioned

by Congress recommended the establishment of a nine-member Board to

oversee the administration of aids to navigation. Staffed with Navy

officers and Engineers from the Army Corps of Engineers, the Lighthouse

Board was established in 1852, relieving Pleasonton from any further

involvement. One of the Board's first orders of priority was the

upgrading of illumination systems from the dim and poorly performing

Lewis Lamps to the far more efficient and powerful Fresnel lenses

manufactured in Paris. To this end, the Lewis lamps were removed from

the Ottawa Point Light in 1856, and replaced with a rotating Fifth Order

Fresnel lens. This lens was designed to exhibit a characteristic fixed

white light with a red flash every ninety seconds. To impart the desired

characteristic, the lens was outfitted with a red bulls eye panel and

was situated atop a cast iron pedestal and equipped with a set of wheels

known as a chariot . A clockwork motor rotated the lens around the lamp

at an exact rotational speed which placed the bulls eyes between the

mariner and the lamp every minute and a half, thereby creating a bright

red flash which permeated the constant white light. In the early 1850's a cry arose in the

maritime community, voicing concern over Pleasonton's tight-fisted

administration of the nation's aids to navigation. A clerical

administrator, Pleasonton had no maritime experience, and it showed-up

in the sub standard workmanship and poorly chosen locations of many of

the lighthouses erected under his administration. A study commissioned

by Congress recommended the establishment of a nine-member Board to

oversee the administration of aids to navigation. Staffed with Navy

officers and Engineers from the Army Corps of Engineers, the Lighthouse

Board was established in 1852, relieving Pleasonton from any further

involvement. One of the Board's first orders of priority was the

upgrading of illumination systems from the dim and poorly performing

Lewis Lamps to the far more efficient and powerful Fresnel lenses

manufactured in Paris. To this end, the Lewis lamps were removed from

the Ottawa Point Light in 1856, and replaced with a rotating Fifth Order

Fresnel lens. This lens was designed to exhibit a characteristic fixed

white light with a red flash every ninety seconds. To impart the desired

characteristic, the lens was outfitted with a red bulls eye panel and

was situated atop a cast iron pedestal and equipped with a set of wheels

known as a chariot . A clockwork motor rotated the lens around the lamp

at an exact rotational speed which placed the bulls eyes between the

mariner and the lamp every minute and a half, thereby creating a bright

red flash which permeated the constant white light.

By 1867, a mere fourteen years after

the station's completion, the Eleventh District Inspector reported that

the pointing between the rubble stones in the tower was falling out, and

that the lantern had deteriorated to the point that water was leaking

into the tower interior, damaging the wooden stairs and leaving the

interior walls in constant state of dampness. He also reported that the

kitchen floor in the dwelling needed replacement, and that a water

supply for the keeper was necessary. However, beyond making minor

"Band-Aid" repairs, the Lighthouse Board elected not to seek

the funds necessary for properly repairing the structures, as it

realized it had problems of significantly higher magnitude to solve on

Ottawa Point.

By virtue of the prevailing Northeast

wind, Ottawa Point had forever been in a state of evolution. Driven by

wave and wind, sand from the lake-bed and the shoreline was continually

deposited onto the end of the Point, changing its configuration. Over

the years since the construction of the Light, this natural reshaping

had continued unabated, lengthening the Point by almost a mile, and

leaving the old lighthouse "high and dry," three quarters of a

mile from the end of the point it was designed to mark. Additionally,

the light had a reputation among mariners as being extremely dim and

difficult to see from out in the Lake. The combination of the dimness of

the light and its distance from the Point represented a disaster waiting

to happen. By virtue of the prevailing Northeast

wind, Ottawa Point had forever been in a state of evolution. Driven by

wave and wind, sand from the lake-bed and the shoreline was continually

deposited onto the end of the Point, changing its configuration. Over

the years since the construction of the Light, this natural reshaping

had continued unabated, lengthening the Point by almost a mile, and

leaving the old lighthouse "high and dry," three quarters of a

mile from the end of the point it was designed to mark. Additionally,

the light had a reputation among mariners as being extremely dim and

difficult to see from out in the Lake. The combination of the dimness of

the light and its distance from the Point represented a disaster waiting

to happen.

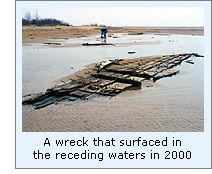

That disaster came when Captain

Olmstead ran his schooner "Dolphin" aground on the Point

beyond the lighthouse during a heavy Southeast gale. Olmstead openly

blamed the "faint flicker" of the lighthouse for the accident,

a cry that was picked up by H. E. Hoard, the editor of the Iosco County

Gazette a few weeks later. In one of his reports on the incident, Hoard

claimed that "this is not the first instance where our feeble

Lighthouse out in the country has proved a snare, instead of a guide." He continued; "Nature has favored us with one of the

best harbors on the lakes, and it would seem that the small amount

necessary to make it safe and easy access, might be appropriated by our

Government, especially when such immense sums are being expended in

other places to build up Harbors of Refuge, Life Saving Stations, etc.,

etc." That disaster came when Captain

Olmstead ran his schooner "Dolphin" aground on the Point

beyond the lighthouse during a heavy Southeast gale. Olmstead openly

blamed the "faint flicker" of the lighthouse for the accident,

a cry that was picked up by H. E. Hoard, the editor of the Iosco County

Gazette a few weeks later. In one of his reports on the incident, Hoard

claimed that "this is not the first instance where our feeble

Lighthouse out in the country has proved a snare, instead of a guide." He continued; "Nature has favored us with one of the

best harbors on the lakes, and it would seem that the small amount

necessary to make it safe and easy access, might be appropriated by our

Government, especially when such immense sums are being expended in

other places to build up Harbors of Refuge, Life Saving Stations, etc.,

etc."

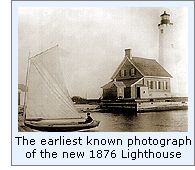

Evidently the combination of the

Lighthouse Board's recommendation, Editor Hoard's protestations, and

added impetus from Michigan's State Representatives made the necessary

impression, with Congress appropriating the sun of $30,000 for the

erection of a new light station during its 1875 session. Eleventh

District Engineer Major Godfrey Weitzel selected a site for the new

station later that year, and drew up plans and specifications for the

station's construction that winter. Title for the site was obtained in

the summer of 1876, and with the delivery of a work crew and materials

to Ottawa Point on August 12, work began at a feverish pace.

As time had proven, the shifting sands

of the entire point created an unsuitable location for a tall tower, and

in order to create a stable base on which the structure could be

erected, an area at the end of the Point was shored-up with a timber

crib. Within this cribwork, timber piles were driven to provide a secure

base on which a circular foundation of cut limestone foundation blocks

were laid. Atop this foundation, a team of masons erected the brick

tower. Standing sixteen feet in diameter at its base, the walls tapered

gracefully to a diameter of nine feet six inches at their uppermost.

Supported by twelve gracefully curved corbels, a copper-clad gallery was

installed and encircled by an iron safety railing. As time had proven, the shifting sands

of the entire point created an unsuitable location for a tall tower, and

in order to create a stable base on which the structure could be

erected, an area at the end of the Point was shored-up with a timber

crib. Within this cribwork, timber piles were driven to provide a secure

base on which a circular foundation of cut limestone foundation blocks

were laid. Atop this foundation, a team of masons erected the brick

tower. Standing sixteen feet in diameter at its base, the walls tapered

gracefully to a diameter of nine feet six inches at their uppermost.

Supported by twelve gracefully curved corbels, a copper-clad gallery was

installed and encircled by an iron safety railing.

A decagonal cast iron lantern was

erected at the center of the gallery, and covered with a tapered copper

roof with ventilator ball, standing sixty-seven feet above grade level.

A lightning rod atop the ventilator ball was attached to a copper cable,

which lead down the outside of the brickwork to a ground stake driven

alongside the foundation. A spiral cast iron staircase with three

landings wound its way within the tower to a hatchway through the

keepers could gain access to the lantern. The 1½ story brick dwelling

was built over a stone-walled cellar, and attached to the tower by a

covered passageway to provide the Keeper access to the tower without

having to leave the warmth of the building during inclement weather. A

cast iron door at the tower end of the passageway was installed to stem

the spread of a possible fire between the two structures. Finally, the

entire crib structure was covered-over with a plank deck to allow the

Keepers easy footing when moving around the station.

Construction was completed as winter

cast its icy grip across Tawas bay, and with the weather too cold to

allow the painting of the tower exterior, and the end of the navigation

season close at hand, the decision was made to postpone exhibiting the

light until the arrival of spring. That winter, the Fifth Order Fresnel

was removed from the old tower, and carefully installed in the new

tower. By virtue of the tower's location atop the cribbed area, the lens

now sat at a focal plane of 70 feet. With the break-up of ice on the

lake. Keeper James Harald climbed to the lantern to exhibit the light in

the new station for the first time on an unrecorded date at the opening

of the 1877 season of navigation. Construction was completed as winter

cast its icy grip across Tawas bay, and with the weather too cold to

allow the painting of the tower exterior, and the end of the navigation

season close at hand, the decision was made to postpone exhibiting the

light until the arrival of spring. That winter, the Fifth Order Fresnel

was removed from the old tower, and carefully installed in the new

tower. By virtue of the tower's location atop the cribbed area, the lens

now sat at a focal plane of 70 feet. With the break-up of ice on the

lake. Keeper James Harald climbed to the lantern to exhibit the light in

the new station for the first time on an unrecorded date at the opening

of the 1877 season of navigation.

In September 1875, an additional crib

protection 130 feet in length and 10 feet in width was erected to a

height of four feet above the lake level at the northwest corner of the

existing crib around the station. This cribwork was filled with

materials removed from the old 1853 tower and dwelling, which had been

demolished after the new station was established.

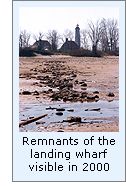

The deck on the crib was replaced in

1890, and with dropping lake levels exposing an ever increasing expanse

of beach around the Point, the landing wharf at the rear of the station

in Tawas Bay was extended 600 feet to reach the three foot water depth.

Also this year, as a result of recurring problems with keeping the

light's rotational speed timed accurately, the District Lampist was

dispatched to the station to inspect the lens rotating mechanisms. While

the Lampist made some adjustments to the chariot at the base of the

lens, the problem was evidently of a nature beyond that which could be

repaired in the field. With the Ottawa Point Light becoming increasingly

important as a guide to mariners coasting the western shore, the

decision was made to both upgrade the lens to one of the Fourth Order

and to modify the characteristic to increase the light's overall

effectiveness. The deck on the crib was replaced in

1890, and with dropping lake levels exposing an ever increasing expanse

of beach around the Point, the landing wharf at the rear of the station

in Tawas Bay was extended 600 feet to reach the three foot water depth.

Also this year, as a result of recurring problems with keeping the

light's rotational speed timed accurately, the District Lampist was

dispatched to the station to inspect the lens rotating mechanisms. While

the Lampist made some adjustments to the chariot at the base of the

lens, the problem was evidently of a nature beyond that which could be

repaired in the field. With the Ottawa Point Light becoming increasingly

important as a guide to mariners coasting the western shore, the

decision was made to both upgrade the lens to one of the Fourth Order

and to modify the characteristic to increase the light's overall

effectiveness.

The new Fourth Order lens was ordered

from Paris, and after receipt at the Detroit depot during the summer of

1891, the District Lampist was again dispatched to Ottawa Point to

undertake the installation. The new lens was officially exhibited for

the first time on the night of September 1, 1891, with its new

characteristic of a repeated 30 second cycle, consisting of fixed white

light for 25 seconds followed by a 5 second eclipse, visible for a

distance of 16 miles.

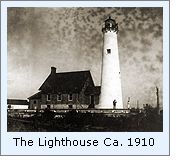

1896 again saw the rebuilding of the

timber platform around the tower and dwelling, and the beginning of a

second extension to the landing wharf at the rear of the station, which

on its completion in 1897, lengthened the wharf by an additional 640

feet.

When the new station was built in 1876,

lard and sperm oil ware used for fueling the lamp. Relatively

non-volatile, the oil was stored in a purpose-built room in the dwelling

cellar. With a change to the significantly more volatile kerosene, a

number of devastating dwelling fires were experienced, and beginning

late in the 1880's the Lighthouse Board embarked upon a program of

erecting separate oil storage buildings at all US light stations. To

this end, a brick oil storage house was built in 1898, six of the timber

cribs supporting the wharf were rebuilt, and the boathouse was rebuilt

at the end of the extended wharf.

As part of a continuing project to

create a network of fog signal stations at lighthouses throughout the

nation, the lighthouse tender AMARANTH arrived at Ottawa Point in the

summer of 1899, and unloaded a working party and materials for the

construction of a brick fog signal building on the Point. Work continued

through the summer, and the single 10-inch steam whistle was placed into

operation on September 28. As was the case with the lighthouse itself, a

timber crib was erected around the fog signal building to both stabilize

the foundation and to prevent the surrounding sands from being washed

away. A boardwalk was laid between the tower and the fog signal, a

telephone system was installed between the dwelling and the fog signal

building, and a new landing dock was erected 1,200 feet to the west of

the fog signal building. Designed for the delivery of coal for the

boilers, a tramway was laid from the new landing dock to the fog signal

building to facilitate the movement of coal from the visiting lighthouse

supply vessels to the bunker in the fog signal building. As part of a continuing project to

create a network of fog signal stations at lighthouses throughout the

nation, the lighthouse tender AMARANTH arrived at Ottawa Point in the

summer of 1899, and unloaded a working party and materials for the

construction of a brick fog signal building on the Point. Work continued

through the summer, and the single 10-inch steam whistle was placed into

operation on September 28. As was the case with the lighthouse itself, a

timber crib was erected around the fog signal building to both stabilize

the foundation and to prevent the surrounding sands from being washed

away. A boardwalk was laid between the tower and the fog signal, a

telephone system was installed between the dwelling and the fog signal

building, and a new landing dock was erected 1,200 feet to the west of

the fog signal building. Designed for the delivery of coal for the

boilers, a tramway was laid from the new landing dock to the fog signal

building to facilitate the movement of coal from the visiting lighthouse

supply vessels to the bunker in the fog signal building.

With the increased workload represented

by the fog signal, the Detroit office determined that the station would

need an Assistant Keeper. However, realizing that the diminutive

dwelling was too small for a second keeper and his family, the

Lighthouse Board requested an appropriation of $5,000 for the

construction of a second dwelling in its annual reports for 1900. George

Galbraeth was appointed as the station's first Assistant on March 16,

1900, and since no arrangements had been made for living accommodations,

we can only surmise that he must have moved into one of the rooms in the

main dwelling. Evidently, Galbraeth was not too enamored with the living

arrangements, as he resigned from lighthouse service on January 31 of

the following year, after less than a year's service. Edward L Sinclair

took over for Galbraeth after transferring-in from Huron Island, where

he had served as Second Assistant for three years.

After the Board's annual pleas for

funding to construct a second dwelling went ignored for five years,

Eleventh District Inspector Commander Herbert Winslow insisted that

arrangements be made for a dwelling for the Assistant, and in 1905 an

abandoned boathouse on the Point was patched-up and converted into a

temporary dwelling for the Assistant Keeper. In a further attempt to

stem erosion, brush and stone revetments were built along the lakeshore

in the vicinity of the fog signal building, and 1,300 willow trees were

planted. The following year, a barn was built, 23 cribs were

reconstructed, and the walks connecting the station with the fog signal

were replaced with concrete slabs which were poured at the Detroit depot

and transported to the site. After the Board's annual pleas for

funding to construct a second dwelling went ignored for five years,

Eleventh District Inspector Commander Herbert Winslow insisted that

arrangements be made for a dwelling for the Assistant, and in 1905 an

abandoned boathouse on the Point was patched-up and converted into a

temporary dwelling for the Assistant Keeper. In a further attempt to

stem erosion, brush and stone revetments were built along the lakeshore

in the vicinity of the fog signal building, and 1,300 willow trees were

planted. The following year, a barn was built, 23 cribs were

reconstructed, and the walks connecting the station with the fog signal

were replaced with concrete slabs which were poured at the Detroit depot

and transported to the site.

Finally in 1922, an existing house in

town was purchased as an Assistant's dwelling, moved to the station, and

erected on a foundation to the north of the tower. Three years later, on

October 27 1925, the 10-inch steam whistle and boilers were removed from

the fog signal building and replaced by a Type F Diaphone signal, and

the characteristic changed to a repeated 60-second cycle consisting of a

blast of 4 seconds, 16 seconds of silence, a second blast of 4 seconds

followed by 36-seconds of silence.

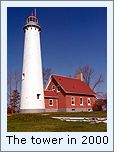

Nature continued to have her way on the

sandy hook of Tawas Point, and the Point continued on its inexorable

growth into Tawas Bay. The elevated timber crib on which the station was

erected was replaced by concrete walls, and the entire area was

graded-over with soil and planted with grass. While the concrete walls

were only visible in a few places, the location of the crib remained

clearly evident as a rectangular raised area on the lawn. By the 1950's, the lighthouse once again stood

too far inland to serve as anything but a coast light. However, with the

introduction of radar and radio, mariners no longer relied as heavily on

the Light, and the tower now served more as a historical artifact than

as a structure of high navigational significance. Thus, the station was

automated and closed in 1953. Keeper Leon DeRosia, who had tended the

Light for the past six years, accepted a transfer to Grays Reef and

departed for his new assignment on Lake Michigan, making him the last

Keeper of the Ottawa Point Light. Nature continued to have her way on the

sandy hook of Tawas Point, and the Point continued on its inexorable

growth into Tawas Bay. The elevated timber crib on which the station was

erected was replaced by concrete walls, and the entire area was

graded-over with soil and planted with grass. While the concrete walls

were only visible in a few places, the location of the crib remained

clearly evident as a rectangular raised area on the lawn. By the 1950's, the lighthouse once again stood

too far inland to serve as anything but a coast light. However, with the

introduction of radar and radio, mariners no longer relied as heavily on

the Light, and the tower now served more as a historical artifact than

as a structure of high navigational significance. Thus, the station was

automated and closed in 1953. Keeper Leon DeRosia, who had tended the

Light for the past six years, accepted a transfer to Grays Reef and

departed for his new assignment on Lake Michigan, making him the last

Keeper of the Ottawa Point Light.

The Coast Guard announced plans to

excess the station in 1996, and ownership of the buildings was

transferred to the Michigan Department of Natural Resources in 2001.

Deciding that it wished to restore the station to its turn of the

twentieth century appearance, in May 2002, the DNR took the

controversial step of demolishing the 1922 Assistant's dwelling. Over

the remainder of the year, over 3 million dollars were spent at the

site, including such improvements as the burial of elevated power lines,

the installation of a new red-painted steel roof on the dwelling and the

installation of flood

lights to illuminate the

tower at night. The Coast Guard announced plans to

excess the station in 1996, and ownership of the buildings was

transferred to the Michigan Department of Natural Resources in 2001.

Deciding that it wished to restore the station to its turn of the

twentieth century appearance, in May 2002, the DNR took the

controversial step of demolishing the 1922 Assistant's dwelling. Over

the remainder of the year, over 3 million dollars were spent at the

site, including such improvements as the burial of elevated power lines,

the installation of a new red-painted steel roof on the dwelling and the

installation of flood

lights to illuminate the

tower at night.

In a rededication ceremony on October 8, DNR Director K

L Cool flipped the switch which light up the tower exterior. The DNR has

plans to completely restore the interior of the tower and dwelling, and

we hope that within the next couple of years the entire structure will

again be open, and the public will again be able to climb the tower to

take in the magnificent view it affords.

Keepers of

this Light

Click here

to see a complete listing of all Tawas Light keepers compiled by Phyllis

L. Tag of Great Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Finding this

Light

Travel northeast from East Tawas on US-23 to Tawas Beach Road. Turn

right on Tawas Beach Road and travel approximately 2-3/4 miles to the

Tawas Point State Park entrance. A motor vehicle permit is required for

entry into the park.

The tower is open to the public From May 15 through October 15 on

Saturdays, Sundays and Holidays.

Contact

Information

Tours can be arranged by contacting (989) 362-5041

Reference

Sources

Inventory of Historic

Light Stations, National Parks Service, 1994 Inventory of Historic

Light Stations, National Parks Service, 1994

Around The Bay, Neil Thornton, Printers Devil Press.

The Detroit News, September 10, 1998

USCG Historian's Office -

photographic archives.

Tawas Point Light, pamphlet, Robert J. Cichocki, USCG Auxiliary

Historian

Photographs from the Neil Thornton collection.

Personal observation at Tawas Point, 05/06/2000

Photographs from the author's personal collection.

Keeper listings for this light appear courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|