|

Historical Information

Sturgeon Point sits approximately halfway between the northern point of

Saginaw Bay and Thunder Bay Island. While the Point lay somewhat off the

main north/south shipping lanes, the Lighthouse Board noted that

"vessels frequently, from various causes, get out of the direct

course, and a light-house at this point would enable them to take a new

departure and shorten the long stretch across the mouth of Saginaw

bay." A shallow reef lurking below the surface for a mile and a

half beyond the Point added to the dangers associated with passing close

by the Point, and estimating that a lighthouse could be erected here for

$15,000, the Lighthouse Board requested an appropriation of that amount

in its annual report for 1866. Congress responded quickly, granting an

appropriation for the requested amount on March 2, 1867.

By July, an agreement had been reached

with local landowner John Sabin for the purchase 60.2 acres of land on

the Point, and title papers had been filed with the US District

Attorney. After plans and specifications for the station were drawn up

and approved on July 6 1868, arrangements were made to begin

construction on the opening of the 1869 navigation season. By July, an agreement had been reached

with local landowner John Sabin for the purchase 60.2 acres of land on

the Point, and title papers had been filed with the US District

Attorney. After plans and specifications for the station were drawn up

and approved on July 6 1868, arrangements were made to begin

construction on the opening of the 1869 navigation season.

Work began with the excavation and

erection of the tower foundation. Consisting of cut limestone blocks,

the foundation stood sixteen feet in diameter; seven feet six inched in

height, with the upper three feet exposed above grade. Atop this

foundation, a team of masons erected the cream city brick tower.

Standing sixteen feet in diameter at its base with its massive walls

four feet six inches in thickness, the walls tapered gracefully to a

diameter of ten feet at their uppermost, at which point they had

narrowed to a thickness of eighteen inches. Supported by ten gracefully

curved corbels, a copper-clad gallery was installed and encircled by an

iron safety railing. Work began with the excavation and

erection of the tower foundation. Consisting of cut limestone blocks,

the foundation stood sixteen feet in diameter; seven feet six inched in

height, with the upper three feet exposed above grade. Atop this

foundation, a team of masons erected the cream city brick tower.

Standing sixteen feet in diameter at its base with its massive walls

four feet six inches in thickness, the walls tapered gracefully to a

diameter of ten feet at their uppermost, at which point they had

narrowed to a thickness of eighteen inches. Supported by ten gracefully

curved corbels, a copper-clad gallery was installed and encircled by an

iron safety railing.

Plans for the two-story dwelling called

for a kitchen, pantry and storeroom on the first floor, and a sitting

room and three bedrooms on the second floor. The dwelling was attached

to the tower by an eleven-foot long covered passageway to provide the

Keeper access to the tower without having to leave the warmth of the

building during inclement weather. A cast iron door at the tower end of

the passageway was installed to stem the spread of a possible fire

between the two structures. Plans for the two-story dwelling called

for a kitchen, pantry and storeroom on the first floor, and a sitting

room and three bedrooms on the second floor. The dwelling was attached

to the tower by an eleven-foot long covered passageway to provide the

Keeper access to the tower without having to leave the warmth of the

building during inclement weather. A cast iron door at the tower end of

the passageway was installed to stem the spread of a possible fire

between the two structures.

By the end of July, the exterior of the

dwelling was complete, and the tower completed to the point that it was

ready to receive the lantern. The decagonal cast iron lantern was

erected at the center of the gallery, and covered with a tapered iron

roof with ventilator ball, standing seventy feet nine inches above grade

level. A lightning rod atop the ventilator ball was attached to a copper

cable, which lead down the outside of the brickwork to a ground stake

driven alongside the foundation. A spiral cast iron staircase with three

landings wound its way within the tower to a hatchway through the

keepers could gain access to the lantern. By the end of July, the exterior of the

dwelling was complete, and the tower completed to the point that it was

ready to receive the lantern. The decagonal cast iron lantern was

erected at the center of the gallery, and covered with a tapered iron

roof with ventilator ball, standing seventy feet nine inches above grade

level. A lightning rod atop the ventilator ball was attached to a copper

cable, which lead down the outside of the brickwork to a ground stake

driven alongside the foundation. A spiral cast iron staircase with three

landings wound its way within the tower to a hatchway through the

keepers could gain access to the lantern.

The station's fixed white Third and a

Half Order lens, had previously been installed in the lighthouse at

Oswego, New York until a characteristic change at that station rendered

the lens obsolete. The lens had been carefully crated and shipped to

Detroit, where it had been in storage for some time. The District

Lampist arrived at Sturgeon Point, and after supervising the movement of

the lens segments into the lantern, assembled the glass gem on a cast

iron pedestal designed to place the "Sweet spot" of the lens

at the required elevation in the lantern.

Perley Silverthorn, a

fisherman and owner of property close to the new station who had been

living in the area since 1854 was appointed as the station's first

Keeper. However, after Silverthorn, his wife Caroline and their four

children failed to report for duty at the station until November 19, it

was deemed too late in the season to exhibit the Light. Thus, on January

2, 1870 an official Notice To Mariners was posted announcing that the

new Light would be lighted on the opening of navigation that spring. Perley Silverthorn, a

fisherman and owner of property close to the new station who had been

living in the area since 1854 was appointed as the station's first

Keeper. However, after Silverthorn, his wife Caroline and their four

children failed to report for duty at the station until November 19, it

was deemed too late in the season to exhibit the Light. Thus, on January

2, 1870 an official Notice To Mariners was posted announcing that the

new Light would be lighted on the opening of navigation that spring.

For reasons that we have as yet been

unable to determine, Silverthorn was removed from his position as Keeper

on August 19, 1873, and Noah T Farr selected as Acting Keeper of the

station, appearing on payroll listings for the station for the first

time on October 14. While Farr was promoted to full Keeper status in

September 1875, his stay at Sturgeon Point was not long-lived, as he

resigned from Lighthouse service on May 18 1876, with John Pasque

appointed to replace him.

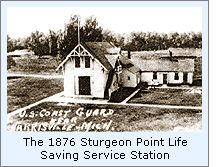

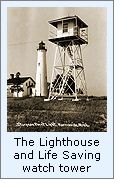

Construction began on a Life-Saving

station at the south of the Lighthouse reservation soon after Pasque's

arrival. On completion of the new station, Perley Silverthorn again made

an appearance at Sturgeon Point, after managing to arrange his

appointment as Keeper of the new Life Saving station. While Silverthorne's

annual pay as keeper of the Life Saving Station was half of the $400 he

earned as a Light keeper, he likely found the new position a great deal

more challenging, as he was now responsible for seven cantankerous

surfmen and living the Service's motto of "You have to go out, but

you don't have to come back." John Pasque accepted a transfer to

the higher paying position of Acting Keeper at Stannard Rock in Lake

Superior on June 6, 1882, and Louis Cardy Sr. was transferred-in from

Skillagallee, where he had hired into lighthouse service as Second

Assistant just two months earlier. Construction began on a Life-Saving

station at the south of the Lighthouse reservation soon after Pasque's

arrival. On completion of the new station, Perley Silverthorn again made

an appearance at Sturgeon Point, after managing to arrange his

appointment as Keeper of the new Life Saving station. While Silverthorne's

annual pay as keeper of the Life Saving Station was half of the $400 he

earned as a Light keeper, he likely found the new position a great deal

more challenging, as he was now responsible for seven cantankerous

surfmen and living the Service's motto of "You have to go out, but

you don't have to come back." John Pasque accepted a transfer to

the higher paying position of Acting Keeper at Stannard Rock in Lake

Superior on June 6, 1882, and Louis Cardy Sr. was transferred-in from

Skillagallee, where he had hired into lighthouse service as Second

Assistant just two months earlier.

By virtue of its location on the flat,

sandy beach on the Point, the light station was at the mercy of the

action of the pounding waves, and by 1885 it was found that the

shoreline had encroached to within forty feet of the tower foundation.

Fearing that continued erosion might compromise the tower's integrity,

the Detroit Depot dispatched a work crew to Sturgeon Point in 1886 to

erect a system of shore protection. Radiating in front of the station,

five timber cribs, each 350 feet in length and 8 feet wide were erected,

and a log breakwater erected along the shoreline to prevent further

undermining.

For unspecified reasons, the station's

lens was damaged in 1887, and sent to the lighthouse Depot at Staten

Island for repair over the winter. Apparently damaged beyond repair, a

new lens was sent to Sturgeon Point, and placed into service on the

opening of the 1888 navigation season. While the cribs and breakwater

installed in 1885 were still in good condition, the decision was made to

augment them with two additional cribs to provide further protection.

With the lowest bid for the work submitted at $1,050.70, Eleventh

District Engineer Major Samuel M. Mansfield felt the bid was excessive,

and decided to have the work done under the supervision of one of the

District's construction foremen. After hiring the needed labor and

purchasing materials on the open market, the work was completed in 1888

for a total of $734.59, representing a thirty percent reduction from the

original low bid. For unspecified reasons, the station's

lens was damaged in 1887, and sent to the lighthouse Depot at Staten

Island for repair over the winter. Apparently damaged beyond repair, a

new lens was sent to Sturgeon Point, and placed into service on the

opening of the 1888 navigation season. While the cribs and breakwater

installed in 1885 were still in good condition, the decision was made to

augment them with two additional cribs to provide further protection.

With the lowest bid for the work submitted at $1,050.70, Eleventh

District Engineer Major Samuel M. Mansfield felt the bid was excessive,

and decided to have the work done under the supervision of one of the

District's construction foremen. After hiring the needed labor and

purchasing materials on the open market, the work was completed in 1888

for a total of $734.59, representing a thirty percent reduction from the

original low bid.

In the early days of the US lighthouse

service, lard and sperm oil ware used for fueling the lamps. Relatively

non-volatile, the oil was stored in special rooms in lighthouse cellars

or in the dwelling itself. With a change to the significantly more

volatile kerosene, a number of devastating dwelling fires were

experienced, and beginning late in the 1880's the Lighthouse Board began

building separate oil storage buildings at all US light stations. To

this end, the metalwork for a sheet iron oil storage building was

delivered at the Detroit depot in 1892, and loaded on the lighthouse

tender AMARANTH late that year. A work crew arrived at the station the

following spring, erected the oil storage structure and installed a

below ground cistern by the dwelling. The downspouts from the dwelling

roof were equipped with diverters, allowing runoff from the roof to flow

directly into the cistern or to be diverted onto the ground. On

completion of the installation, the pump at the sink in the dwelling

kitchen was re-plumbed so as to draw its water from the cistern. In

practice, the keepers kept the diverters closed so when rain came they

would allow the rainwater to clean the roof for a period of time before

opening the diverters to allow the water to enter the cistern. While to

our twenty-first century sensibilities, the practice of drinking and

cooking with water that had run from the roof sounds disgusting, it was

a commonplace practice at light stations in the late 1800's.

Rapid advancements in the application

of acetylene for lighthouse illumination at the turn of the twentieth

century, coupled with the invention of the sun valve, afforded the

Lighthouse Service the opportunity to experiment with automating a

number of Lights around the Great Lakes. In 1907, the Charity Island

Light was thus automated, and Sturgeon Point followed in 1913. With the

installation of the acetylene equipment, the characteristic of the light

was also changed from fixed white to flashing white every 3 seconds.

Keeper Cardy also passed away in 1913, making him the last full-time

Keeper to be assigned to the station. It is possible that the need to

find a Keeper to replace Cardy may have served as the District's primary

motivating factor in its automation of Sturgeon Point. With automation,

responsibility for maintenance of the light was turned over to the Coast

Guardsmen at the Life Saving station. Rapid advancements in the application

of acetylene for lighthouse illumination at the turn of the twentieth

century, coupled with the invention of the sun valve, afforded the

Lighthouse Service the opportunity to experiment with automating a

number of Lights around the Great Lakes. In 1907, the Charity Island

Light was thus automated, and Sturgeon Point followed in 1913. With the

installation of the acetylene equipment, the characteristic of the light

was also changed from fixed white to flashing white every 3 seconds.

Keeper Cardy also passed away in 1913, making him the last full-time

Keeper to be assigned to the station. It is possible that the need to

find a Keeper to replace Cardy may have served as the District's primary

motivating factor in its automation of Sturgeon Point. With automation,

responsibility for maintenance of the light was turned over to the Coast

Guardsmen at the Life Saving station.

With the Coast Guard's complete assumption of

responsibility for the nation's aids to navigation in 1939, and the

running of electrical power out to Sturgeon Point, the light was

electrified through the installation of an incandescent bulb in the lens

that same year. While Coast Guardsmen continued to tend the light for a few years thereafter, the

station's importance waned, and it appears that the last crew left the

Sturgeon Point station in 1941.

No longer inhabited, the wooden

structures of the Life Saving station deteriorated rapidly, and

constituting an attractive nuisance, were subsequently destroyed. The

lighthouse dwelling and tower were vandalized, however their sturdy

brick construction limited the damages to windows, doors and interior

walls and woodwork. The Alcona Historical Society obtained a lease to

the lighthouse structures in 1982, and began an intensive three-year

volunteer restoration project. The dwelling now serves as a maritime

museum, and is open to the public seven days a week from Memorial Day to

mid September. The grounds are open to the public all year.

Keepers of

this Light

Click here

to see a complete listing of all Sturgeon Point Light keepers compiled

by Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Seeing this Light

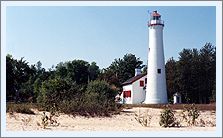

Sturgeon Point lighthouse is one of the most picturesque to be found in

the area. The stark contrast of the bright white painted bricks with the

deep red trim makes the building very photogenic. Sitting on the shore

end of a long and shallow submerged finger of land that juts into Lake

Huron, it is plain to see why a lighthouse was needed here in the days

before radar and Loran.

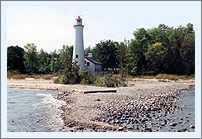

Leaving most of the camera gear hidden in some

scrub bushes, we gingerly made our way out into the water to capture the

image seen in the upper right, the rocks making the way uncomfortable to

our bare feet. We then toured the building, which has been completely

restored in a very tasteful manner, giving the appearance that the

keeper had just left some of the rooms ahead of us. Unfortunately, the

tower was not open to the public, as it is still used as an active aid

to navigation. Interestingly, we could see no remaining signs of the

shore protection cribs and piers that were installed in the 1880's.

Returning to our truck, I realized that my glasses were

missing, and retracing our steps through the grounds, we found them

lying beneath the bush where we had left the photo equipment earlier.

Finding this

Light

Take US 23 North approximately three miles out of Harrisville, turn

right onto Lakeshore Drive and continue approximately one mile to Point

Road. Turn East on to Point Road, and continue approximately one mile to

the gravel road on the left that enters the lighthouse parking area. It

is a short walk further down this road to this charming lighthouse.

Contact

information

Sturgeon Point Lighthouse & Maritime Museum

Sturgeon Point Road

Harrisville, MI 48740

(517) 724-5107

Reference

Sources Reference

Sources

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Board, various, 1867 - 1909

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Service, 1910 - 1929

Annual reports of the Lake Carrier's Association, 1908 - 1930

Telephone call to Don Sawyer, VP Alcona Historical Society,

6/1/2000

USCG Historian's Office -

photographic archives.

The Northern Lights, Charles K Hyde, 1986

Personal observation at Sturgeon Point, 09/11/1998

Photographs from the author's personal collection.

Keeper listings for this light appear courtesy of Tom & Phyllis Tag

|