|

Historical Information As a stopgap measure, the Lighthouse Board installed a buoy marking the reef in 1868. However, realizing that such a marker would only serve useful during daylight hours, a full survey was conducted early the following year in order to validate the feasibility of constructing a permanent light station on the reef. With the survey result proving positive, the Lighthouse Board immediately began petitioning Congress for the appropriation of the necessary funds to move ahead with the project. Pleading that Spectacle Reef was "probably more dreaded by navigators than any other danger now unmarked throughout the entire chain of lakes," they surmised that the loss of the two schooners the previous year likely involved a loss greater than the predicted $300,000 cost of a permanent station. Congress reacted favorably, and appropriated $100,000 to commence construction, with an additional $100,000 to continue construction during the second year. Orlando M. Poe was placed in charge of the project and under his supervision work began in 1870 with the establishment of a base of operation sixteen miles northwest of Spectacle Reef at Scammon's Harbor. The location chosen by Poe for construction of the light was found to be directly over the wreckage of the Nightingale and her cargo of iron ore, one of the two vessels destroyed on the reef three years previous. Since the surveys indicated that this was the only suitable location for construction, part of the wreckage had to be cleared before on-site construction could begin.

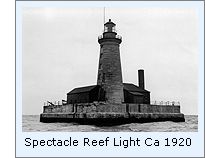

On July 18th 1871, the tugs CHAMPION and MAGNET, accompanied by a flotilla of support vessels and one hundred and forty workers, towed the crib to the reef. At six-thirty on the morning of the next day, the crib was in position, and all hands began the process of loading rocks into compartments built into the crib. By the next morning, 1,200 tons of ballast had been added, and the crib was in place on the reef. With the construction of workers' quarters on the pier, a Fourth Order Fresnel was temporarily installed on the roof of one of the buildings, and work on Spectacle Reef began in earnest. After a diver had been sent down to level the rock at the bottom of the central opening in the crib, a forty-one foot diameter cofferdam was constructed within the central opening. Similar in construction to a barrel, the cofferdam was a cylinder composed of four by six-inch wooden staves, internally braced, and held tightly by iron hoops around its perimeter. The bottom of the cofferdam was then sealed with Portland cement, and the process of pumping the water from within the cofferdam began. On October 14, the water was sufficiently removed to allow stonecutters to begin work leveling off the bedrock on which the foundation would be located. Since this leveling was being accomplished within the confines of the forty-one foot diameter cofferdam, which in-turn held back the waters of the lake, no explosives could be used, and the entire process had to be accomplished through the use of hand tools. After two weeks, the first course of dressed stone blocks was bolted in place, when the weather turned foul, work stopped, and the crew returned to the mainland. The two keepers of the Fourth Order Fresnel remained on the crib through the end of the shipping season, when the lighthouse tender Haze took them off, and the construction site was abandoned to the elements for the winter. Work began the following spring after the solid mass of ice surrounding the crib was removed through a combination of hacking and natural melting. Originally planned to be built with stone from a quarry in Duluth, the supplier fell short in living up to his commitments, and thus the stone was cut and dressed in the Marblehead Quarry in Ohio, and shipped to Spectacle Reef. Each course of stone in the growing pier was anchored to the prior course with three-foot long iron bolts set in Portland cement. With completion of the granite pier, the limestone tower took shape. Featuring five floors, each consisting of a single room fourteen feet in diameter, with walls five and a half feet thick at the base, tapering to sixteen inches thick at the top, and a total structure height of ninety-three feet from bedrock to it's top. Construction was almost complete in the fall of 1873, when once again the onset of winter's storms forced the work site to be abandoned until the following Spring. Returning to Spectacle Reef in May 1874, the crew found the station caked in ice to a height of thirty feet, well above the entrance door. Thus they found themselves in a situation in which they had to spend many days hacking away at the ice before they could gain entrance to the tower to complete construction. With the installation of the Cast Iron lantern room, and the foot-tall Second Order Fresnel lens, the work was complete, and the light was exhibited for the first time in June of that year. The light's first Illumination must have been a wondrous site, since sitting with a focal plane of eighty-six feet, the Fresnel output an incredible 400,000 candlepower.

Keepers continued to tend the light at

Spectacle Reef for ninety-eight years until the Coast Guard automated

the light in 1972. The Fresnel was removed from the tower in 1982, when

it was replaced with a solar powered optic. The lens was then carefully

disassembled, crated, and shipped to the Great Lakes Historical Society

Museum in Vermilion Ohio, where it is a featured component of their

exhibit. To this day, Spectacle Reef Light is considered one of the

premier examples of monolithic stone masonry in the United States. |

Poe's plan was to construct a

ninety-two foot square wooden with a forty-two foot opening in its

center at Scammon's Harbor, and subsequently tow the crib to the reef.

Placed over the desired location, the crib would then be sunk through

the addition of rocks in compartments built for the purpose within its

walls. In place on the reef, the crib was to serve as a working

platform, with the light station constructed within the central opening.

Poe's plan was to construct a

ninety-two foot square wooden with a forty-two foot opening in its

center at Scammon's Harbor, and subsequently tow the crib to the reef.

Placed over the desired location, the crib would then be sunk through

the addition of rocks in compartments built for the purpose within its

walls. In place on the reef, the crib was to serve as a working

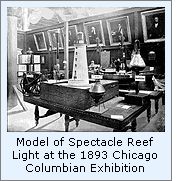

platform, with the light station constructed within the central opening. With a final cost of construction of $406,000, the project

was an immense undertaking. The Lighthouse Board was justifiably proud

of their accomplishment, and a model of the light was featured in the

Aids to Navigation display at the 1893 Columbian Exhibition in Chicago.

With a final cost of construction of $406,000, the project

was an immense undertaking. The Lighthouse Board was justifiably proud

of their accomplishment, and a model of the light was featured in the

Aids to Navigation display at the 1893 Columbian Exhibition in Chicago.