|

Historical Information

In 1838, P C Austin arrived in the

area that would eventually receive his name, and established a lumber

mill and dock from which he planned to ship the bounty of the Thumb

area's forests. Although a number of attempts to secure federal funding

for harbor improvements at Port Austin ware undertaken by Michigan's

State Representatives through the 1860's, Port Austin itself would never

attain any great prominence as a shipping point.

However, by the mid-1870's, the reef

lying 1.7 miles to the northwest off Point Aux Barques had become a

critical obstacle in the path of the growing numbers of mariners

rounding the point in and out of Saginaw Bay. With a but a few small

portions awash, the majority of the craggy reef lurked just below the

surface, waiting to tear the hull of any mariner unfamiliar with the

areas navigation intricacies. Congress appropriated the sum of $10,000

for the construction of a light to mark Port Austin Reef on March 3,

1873, and Eleventh District Engineer Major Godfrey Weitzel dispatched a

survey crew to Port Austin that same year to select a site for the new

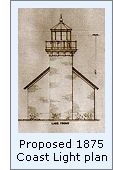

light. After two years of unsuccessful negotiations, an alternate site

with a more willing owner some 200 feet eastward was selected in 1875,

and Weitzel drew up plans for a 1½-story brick dwelling with integrated

tower similar to that which would also be built at Sand Point on Lake

Superior in 1878 and at Little Traverse in 1884. The plans were approved

by the Lighthouse Board on September 6, 1875, and construction at Port

Austin scheduled to begin at the opening of navigation the following

year. However, by the mid-1870's, the reef

lying 1.7 miles to the northwest off Point Aux Barques had become a

critical obstacle in the path of the growing numbers of mariners

rounding the point in and out of Saginaw Bay. With a but a few small

portions awash, the majority of the craggy reef lurked just below the

surface, waiting to tear the hull of any mariner unfamiliar with the

areas navigation intricacies. Congress appropriated the sum of $10,000

for the construction of a light to mark Port Austin Reef on March 3,

1873, and Eleventh District Engineer Major Godfrey Weitzel dispatched a

survey crew to Port Austin that same year to select a site for the new

light. After two years of unsuccessful negotiations, an alternate site

with a more willing owner some 200 feet eastward was selected in 1875,

and Weitzel drew up plans for a 1½-story brick dwelling with integrated

tower similar to that which would also be built at Sand Point on Lake

Superior in 1878 and at Little Traverse in 1884. The plans were approved

by the Lighthouse Board on September 6, 1875, and construction at Port

Austin scheduled to begin at the opening of navigation the following

year.

Work was about to commence in the

spring of 1876, when the Lighthouse Board convinced Congress that the

nature of the danger at Port Austin lent itself more appropriately to

the erection of an offshore light to mark the northern extremity of the

reef. Major Weitzel estimated that the revised project could be brought

to completion for an additional $75,000 by locating the keeper's

dwelling onshore on the reservation already purchased, thereby

eliminating the costs of building extensive living quarters on the

offshore crib. Congress made the necessary appropriation on July 31,

1876, and perhaps skeptical of Weitzel's estimate, included the wording

that "the appropriation heretofore made for a light-house at Port

Austin, Michigan, may be expended in commencing the construction of the

proposed light-house on the reef instead of on the shore, provided the

total estimate for its completion shall not exceed eighty-five thousand

dollars."

Construction began in early July 1878

at both Tawas and on the reef off Port Austin. On the reef, a crew

worked to clear and level the selected area in four feet of water at the

northwest end of the reef where the crib would eventually be placed. At

Tawas, where a ready supply of timber could be obtained, work began on

the construction of the crib that would form the core of the offshore

pier itself. A massive octagonal structure, eighty feet in diameter and

six feet in height, the crib form was constructed of twelve-inch square

oak timbers. Assembled on a timber skid-way down which it would

eventually slide into the water, the cribs inner cross members were

secured with three-foot long iron bolts, and the outer timbers secured

to the inner cross members with over 500 iron bolts, each five feet in

length.

The crib was lowered down the greased

skid-ways into the water, and towed into the open water of Saginaw Bay

in early August. From there, it was carefully towed to Pointe aux

Barques, where an additional four feet of height was added, increasing

the total height of the structure to ten feet. On Sunday August 12,

1877, the completed crib was towed out to the reef, and carefully

centered over the previously cleared and leveled area. A number of doors

in the exterior walls of the crib were opened, allowing water to flow

into sealed pockets within the crib, thereby overcoming the crib's

buoyancy, and lowering it to the prepared rock bottom. The crib was then

secured to the rock bottom with 150 three-inch diameter bolts, seven

feet in length which were sunk through the base of the crib and anchored

with wedges into the rock. Rope caulk and Portland cement were then used

to seal the gaps between the base of the timber crib and the prepared

surface of the rock, and the water within the crib was pumped out. With

the crib now securely anchored to the reef, all eight faces were covered

with a veneer of hard brick to a height of 29 feet. Within these hard

brick walls, fourteen thousand barrels of cement and seven hundred cords

of crushed stone quarried at Grindstone City were poured into the

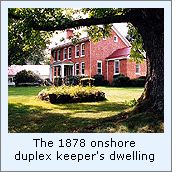

structure to form the final pier. Work on onshore keeper's dwelling

reached completion in early July 1878, and the crew turned 100% of its

attention to the construction of the tower on the pier. The crib was lowered down the greased

skid-ways into the water, and towed into the open water of Saginaw Bay

in early August. From there, it was carefully towed to Pointe aux

Barques, where an additional four feet of height was added, increasing

the total height of the structure to ten feet. On Sunday August 12,

1877, the completed crib was towed out to the reef, and carefully

centered over the previously cleared and leveled area. A number of doors

in the exterior walls of the crib were opened, allowing water to flow

into sealed pockets within the crib, thereby overcoming the crib's

buoyancy, and lowering it to the prepared rock bottom. The crib was then

secured to the rock bottom with 150 three-inch diameter bolts, seven

feet in length which were sunk through the base of the crib and anchored

with wedges into the rock. Rope caulk and Portland cement were then used

to seal the gaps between the base of the timber crib and the prepared

surface of the rock, and the water within the crib was pumped out. With

the crib now securely anchored to the reef, all eight faces were covered

with a veneer of hard brick to a height of 29 feet. Within these hard

brick walls, fourteen thousand barrels of cement and seven hundred cords

of crushed stone quarried at Grindstone City were poured into the

structure to form the final pier. Work on onshore keeper's dwelling

reached completion in early July 1878, and the crew turned 100% of its

attention to the construction of the tower on the pier.

Under normal

circumstances, one would have expected that such an impressive pier

structure would have been topped by an equally impressive tower.

However, forced to work within the limitations of the $85,000

appropriation, the pier was instead capped with a timber-framed tower of

a similar design to that normally used for pierhead beacons. Standing 57

feet in height, the pyramid timber-framed tower was sheathed to contain

rooms below the lantern in which the keepers could store wicks and oil

and take shelter while tending the light. The tower was capped with an

octagonal cast iron lantern outfitted with a clear Fourth Order Fresnel

lens manufactured by Henry Lepaute of Paris. Equipped with red flash

panels, the lens rotated around the lamp by means of a clockwork motor.

The rotation speed of this motor was carefully adjusted and maintained

to place the flash panels in front of the lantern in such a way as to

display the station's characteristic two minute cycle, consisting of a

minute of steady white light, followed by a group of five red flashes

every 12 seconds. Under normal

circumstances, one would have expected that such an impressive pier

structure would have been topped by an equally impressive tower.

However, forced to work within the limitations of the $85,000

appropriation, the pier was instead capped with a timber-framed tower of

a similar design to that normally used for pierhead beacons. Standing 57

feet in height, the pyramid timber-framed tower was sheathed to contain

rooms below the lantern in which the keepers could store wicks and oil

and take shelter while tending the light. The tower was capped with an

octagonal cast iron lantern outfitted with a clear Fourth Order Fresnel

lens manufactured by Henry Lepaute of Paris. Equipped with red flash

panels, the lens rotated around the lamp by means of a clockwork motor.

The rotation speed of this motor was carefully adjusted and maintained

to place the flash panels in front of the lantern in such a way as to

display the station's characteristic two minute cycle, consisting of a

minute of steady white light, followed by a group of five red flashes

every 12 seconds.

Three keepers were selected to man the

station. Charles Kimball, who has served six years as First Assistant at

Pointe aux Barques was promoted to the position of Acting Keeper of the

new station, and Aron Peer was hired to fill the position of his First

Assistant. Evidently Kimball pulled some political strings to get his

brother Alonzo hired as the station's 2nd Assistant, since Alonzo had

previously been removed from lighthouse service in 1886 when he was 1st

Assistant at Pointe aux Barques. Kimball and Peer arrived and moved into

the dwelling on September 9, exhibiting the light from the frame tower

for the first time on the evening of September 15, 1878, and Alonzo

reported for duty on October 18. All told, Weitzel was able to bring the

project to completion for the sum of $81,871, almost $3,000 under

budget.

In 1882, two wood frame buildings were

erected on the crib to house duplicate steam engines which powered twin

fog sirens. Problems with the fog signal's location on the crib some 33

feet above the water quickly surfaced, with the boilers becoming starved

for water due to distance the water had to be raised. To this end, the

valves in the suction pipe were replaced in 1886. However this repair

still proved insufficient, and a high-capacity force pump was added the

following year. Still encountering problems with the water supply, large

wooden reservoir tanks were installed in the signal house in 1888, to

provide a ready supply of water to be drawn by the engines as needed and

replaced by the force pump. Also in this year, the well at the keeper's

dwelling onshore was cleaned out, lined with stone, and outfitted with a

new pump. As part of a general system-wide upgrade, the materials

required for replacing the sirens with 10-inch steam whistles were

delivered at the opening of the 1895 navigation season, with a work crew

arriving at the station early that summer and completing the change-over

on June 30.

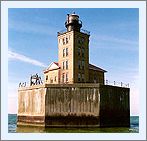

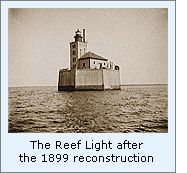

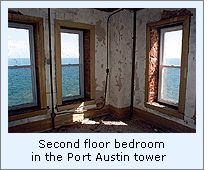

By the end of the nineteenth century,

both the surfaces of the pier and the wood frame tower were showing

signs of the ravages of the weather, and plans were drawn up for a major

upgrade of the structures. In the summer of 1899, a work crew and

materials were delivered at the pier, and by the end of the year, a

resurfacing of the pier was completed, the landing crib on the south

side of the pier was rebuilt and a boat crane and stairway installed.

Thousands of tan bricks from a local brickyard were delivered and the

masons began erecting a new 60-foot tall tower. Standing 16 feet square,

the tower was constructed with double walls, the inner walls being 4

inches in thickness and the outer walls 13 inches thick with a 3-inch

air space between. While the onshore dwelling would continue to serve as

primary living quarters for the keepers, the tower included four floors,

each consisting of a single room with four windows in each providing

views to the south and east. The first floor served as a kitchen and

dining area, and the upper three floors as bedrooms and an office. By the end of the nineteenth century,

both the surfaces of the pier and the wood frame tower were showing

signs of the ravages of the weather, and plans were drawn up for a major

upgrade of the structures. In the summer of 1899, a work crew and

materials were delivered at the pier, and by the end of the year, a

resurfacing of the pier was completed, the landing crib on the south

side of the pier was rebuilt and a boat crane and stairway installed.

Thousands of tan bricks from a local brickyard were delivered and the

masons began erecting a new 60-foot tall tower. Standing 16 feet square,

the tower was constructed with double walls, the inner walls being 4

inches in thickness and the outer walls 13 inches thick with a 3-inch

air space between. While the onshore dwelling would continue to serve as

primary living quarters for the keepers, the tower included four floors,

each consisting of a single room with four windows in each providing

views to the south and east. The first floor served as a kitchen and

dining area, and the upper three floors as bedrooms and an office.

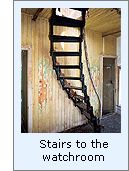

The tower was capped with a square cast

iron gallery with hand railing, centered on which a circular cast iron

watch room was erected. This watchroom was lined with oak bead board and

featured four brass portholes offering a view of the lake in each

direction, and supported a circular gallery and cast iron lantern. With

an inner diameter of almost 8 feet, as was the case with almost all

lanterns installed at this time, the curved lantern glass was set in

thin diagonal astragals to provide a virtually uninterrupted focal plane

for the lens. At the end of the 1899 navigation season, the lens from

the frame tower was disassembled and reinstalled atop the new tower from

whence it was exhibited for the first time of the opening of the 1900

season of navigation. In its new location, the lens sat at a focal plane

of 76 feet, with a resulting range of visibility of 16 ½ miles.

Integrated into the southwest corner of the tower, a 34 foot square

hip-roofed fog signal building was constructed of similar brick and

construction, and both steam boilers placed onto elevated pads at the

building's center. The tower was capped with a square cast

iron gallery with hand railing, centered on which a circular cast iron

watch room was erected. This watchroom was lined with oak bead board and

featured four brass portholes offering a view of the lake in each

direction, and supported a circular gallery and cast iron lantern. With

an inner diameter of almost 8 feet, as was the case with almost all

lanterns installed at this time, the curved lantern glass was set in

thin diagonal astragals to provide a virtually uninterrupted focal plane

for the lens. At the end of the 1899 navigation season, the lens from

the frame tower was disassembled and reinstalled atop the new tower from

whence it was exhibited for the first time of the opening of the 1900

season of navigation. In its new location, the lens sat at a focal plane

of 76 feet, with a resulting range of visibility of 16 ½ miles.

Integrated into the southwest corner of the tower, a 34 foot square

hip-roofed fog signal building was constructed of similar brick and

construction, and both steam boilers placed onto elevated pads at the

building's center.

In 1902, the landing pier and boat

house at the dwelling were completely rebuilt. The stairway leading from

the boathouse up the bank to the dwelling was also renewed, as were the

concrete sidewalks around the dwelling. In 1915, the lamp was upgraded

to an incandescent oil vapor (IOV) unit, increasing the output to 4,000

candlepower. At this same time, the characteristic of the light was also

changed to a repeated 12 second cycle consisting of red flashes of 1.4

seconds in duration followed by 10. 6 second eclipses. In 1902, the landing pier and boat

house at the dwelling were completely rebuilt. The stairway leading from

the boathouse up the bank to the dwelling was also renewed, as were the

concrete sidewalks around the dwelling. In 1915, the lamp was upgraded

to an incandescent oil vapor (IOV) unit, increasing the output to 4,000

candlepower. At this same time, the characteristic of the light was also

changed to a repeated 12 second cycle consisting of red flashes of 1.4

seconds in duration followed by 10. 6 second eclipses.

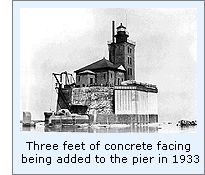

With recent advances in fog signal

technology, a work crew again returned to the pier in 1933 to replace

the 38 year old 10-inch steam whistles with a pair of compressed air

operated "Type F" diaphones. Operated by diesel-powered air

compressors, these new diaphones represented a significant advantage

over the steam-powered whistles in that they could be operating within

minutes of discovering that visibility was decreasing, whereas the old

steam units took up to an hour to build sufficient steam before they

could be sounded. To provide a mounting location for the trumpet-like

resonators which projected the sound of the diaphone across the water, a

gable was added to the roof of the signal building. With this new

installation, the fog signal characteristic was also changed to a

repeated one minute cycle consisting of a first blast of 3 seconds

followed by a silent interval of 3 seconds, a second blast of 3 seconds

followed by 51 seconds of silence. Finally, the work crew added three

feet of concrete facing to all eight sides of the pier to protect its

weathering surface. With recent advances in fog signal

technology, a work crew again returned to the pier in 1933 to replace

the 38 year old 10-inch steam whistles with a pair of compressed air

operated "Type F" diaphones. Operated by diesel-powered air

compressors, these new diaphones represented a significant advantage

over the steam-powered whistles in that they could be operating within

minutes of discovering that visibility was decreasing, whereas the old

steam units took up to an hour to build sufficient steam before they

could be sounded. To provide a mounting location for the trumpet-like

resonators which projected the sound of the diaphone across the water, a

gable was added to the roof of the signal building. With this new

installation, the fog signal characteristic was also changed to a

repeated one minute cycle consisting of a first blast of 3 seconds

followed by a silent interval of 3 seconds, a second blast of 3 seconds

followed by 51 seconds of silence. Finally, the work crew added three

feet of concrete facing to all eight sides of the pier to protect its

weathering surface.

1937 saw the addition of

three feet of

concrete to all sides of the pier, faced with steel plates from the rock

bottom to approximately six feet above the water line to protect the

concrete from the grinding action of the ice. With the transfer of

responsibility of the nation's aids to navigation to the Coast Guard in

1939, a submarine electric cable was run from the shore out to the pier,

allowing the installation of electric lighting in the fog signal and

tower, and the replacement of the IOV lamp in the lantern with a 25,000

candlepower incandescent electric bulb, without any change in the

light's characteristic. The Fresnel lens was removed from the lantern

three years later, to be replaced by a 300 mm glass lens, and the

characteristic again changed to a repeated one second flash followed by

a 9 second eclipse. The light was completely automated in 1953,

eliminating the need for full time keepers at the station. No longer

serving any purpose, the onshore dwelling was sold into private

ownership at some time thereafter. 1937 saw the addition of

three feet of

concrete to all sides of the pier, faced with steel plates from the rock

bottom to approximately six feet above the water line to protect the

concrete from the grinding action of the ice. With the transfer of

responsibility of the nation's aids to navigation to the Coast Guard in

1939, a submarine electric cable was run from the shore out to the pier,

allowing the installation of electric lighting in the fog signal and

tower, and the replacement of the IOV lamp in the lantern with a 25,000

candlepower incandescent electric bulb, without any change in the

light's characteristic. The Fresnel lens was removed from the lantern

three years later, to be replaced by a 300 mm glass lens, and the

characteristic again changed to a repeated one second flash followed by

a 9 second eclipse. The light was completely automated in 1953,

eliminating the need for full time keepers at the station. No longer

serving any purpose, the onshore dwelling was sold into private

ownership at some time thereafter.

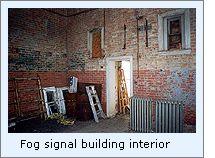

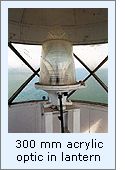

The 300 mm glass lens was removed in

1985, and replaced by a 12-volt solar powered Tidelands Signal 300 mm

acrylic optic, eliminating the need for ongoing maintenance of the

submarine cable. Without the constant care of full-time keepers, the

structure began to deteriorate, with the fog signal building roof

caving-in, allowing the weather and thousands of birds to wreak havoc on

the building's interior. To exacerbate the problem, vandals had broken

out most of the windows and doors, and stolen anything that could be

removed from the structure. Without the necessary manpower and funds to

make necessary repairs, the Coast Guard formulated plans to demolish the

buildings and replace them with a low-maintenance skeletal metal tower

to house the solar-powered light. The 300 mm glass lens was removed in

1985, and replaced by a 12-volt solar powered Tidelands Signal 300 mm

acrylic optic, eliminating the need for ongoing maintenance of the

submarine cable. Without the constant care of full-time keepers, the

structure began to deteriorate, with the fog signal building roof

caving-in, allowing the weather and thousands of birds to wreak havoc on

the building's interior. To exacerbate the problem, vandals had broken

out most of the windows and doors, and stolen anything that could be

removed from the structure. Without the necessary manpower and funds to

make necessary repairs, the Coast Guard formulated plans to demolish the

buildings and replace them with a low-maintenance skeletal metal tower

to house the solar-powered light.

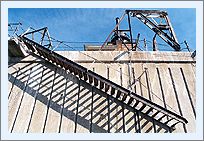

On learning of the plans to demolish

the station, Port Austin businessman Louis Shillinger gathered together

with a number of acquaintances to form the Port Austin Reef Light

Association. A non profit corporation chartered to restore and maintain

the station, PARLA obtained a five year license from the Coast Guard in

1988, and set about the daunting task of stabilizing the deteriorating

structure. Over the following two years, the decaying roof on the fog

signal building was completely removed and new trusses and decking were

installed. The decking was then covered with galvanized metal shingles,

and painted a historically accurate bright red. A railing was added to

the access ladder, the safety chains around the edge of the deck were

replaced, a new brick chimney was installed, and 18 windows were removed

and replaced. In 1990, PARLA's license to renovate the structure was

extended an additional thirty years through 2020. On learning of the plans to demolish

the station, Port Austin businessman Louis Shillinger gathered together

with a number of acquaintances to form the Port Austin Reef Light

Association. A non profit corporation chartered to restore and maintain

the station, PARLA obtained a five year license from the Coast Guard in

1988, and set about the daunting task of stabilizing the deteriorating

structure. Over the following two years, the decaying roof on the fog

signal building was completely removed and new trusses and decking were

installed. The decking was then covered with galvanized metal shingles,

and painted a historically accurate bright red. A railing was added to

the access ladder, the safety chains around the edge of the deck were

replaced, a new brick chimney was installed, and 18 windows were removed

and replaced. In 1990, PARLA's license to renovate the structure was

extended an additional thirty years through 2020.

Since that time, exterior doors have

been replaced, bricks have been tuck pointed, and various painting and

maintenance tasks have been undertaken. PARLA has plans to completely

restore the interior of the station, and welcomes anyone who is

interested in donating their time, money or materials to the project of

helping return the station to its original utilitarian glory.

Keepers of

this Light

Click here

to see a complete listing of all Port Austin Reef Light keepers compiled

by Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Seeing this light

A couple of members of PARLA kindly agreed to show

us around the station in September 2002. After meeting for breakfast on

a fine, sunny September morning, we boarded the thirty foot pontoon boat

which serves as PARLA's working platform for the ten minute trip out to

the light. As we approached the light, we could see that cormorants were

sitting on the cranes and railings, and after making our way to the deck

level we could see first-hand the damage done buy these birds. We

learned that while the birds still leave their "greeting

cards" all over the structure, it pales in comparison to what the

PARLA folks found when they first went out to the station in 1988. As a

result of the huge holes in the roof and the missing windows, their

first task was to remove over a foot of bird and bat droppings from

every floor in the structure, carting the messy residue to shore for

proper disposal.

We spent a pleasant and

very informative two and a half hours exploring every nook and cranny of

the station, before making the trip back to shore, and heading south to

revisit the Pointe aux Barques Light.

Finding this

Light

Since public tours are of the light are not currently available, a

distant view of the station may be obtained from the docks of the public

marina located in downtown Port Austin. Close-up view of the lighthouse

can be obtained by private or chartered boat, and there are excellent

launch facilities at the public dock. However, extreme caution must be

taken when approaching the light due to the shallow water that covers

the rocks on which the light is located in all directions. There are

also a number of charter boat captains operating out of Port Austin with

whom it is likely that a trip out to view the light from the water could

be arranged for a reasonable fee.

Contact Information

Port Austin Reed Light Association

P.O. Box 546

Port Austin, MI 48467

Reference

Sources

Journal of the US Senate, 1867 Journal of the US Senate, 1867

Congressional Journal, 1868, 1873

Detroit Free Press, August 1877

Scott's New Coast Pilot, 1888

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Board,

1874 through 1909

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Service, 1910 through 1939

Great Lakes Light Lists, 1901, 1928, 1939, 1958

Great Lakes Pilot,

2000, NOAA

Northern Lights, Charles K. Hyde, 1995

Pamphlet produced by

PARLA for 1999 lighthouse centennial

Discussion with Lou Shillinger

during 09/14/02 visit to Port Austin.

Keeper listings for this light appear courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|