|

Historical information

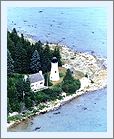

At the dawn of the nineteenth century, the spit of land

protruding from the eastern shore of Lake Huron had already been known

as Presque Isle for over a hundred years, after French trappers seeking

welcome shelter in the natural harbor on the peninsula's southern lee

side gave it the name "almost an island." By 1830 the area

took on additional significance, as steam-powered vessels began stopping

here to stock up on wood to feed their hungry boilers. So important was

this natural harbor of refuge that many an upbound captain decided to

turn tail back to Fort Gratiot finding himself unable to make the safety

of Presque Isle during a gut-busting Nor'wester.

Taking up the call of maritime

interests on February 19, 1838, Michigan State Representative Isaac

Crary beseeched Congress to consider funding the construction of a

lighthouse to guide vessels into Presque Isle harbor. The matter was

referred to the Committee on Commerce, and after receiving a positive

report Congress appropriated the sum of five thousand dollars for the

project on July 7, only five months after Crary introduced his

recommendation. That fall, Lieutenant James T. Homans was dispatched to

select sites for the lighthouse at Presque Isle, along with sites for

other new lights appropriated for Point-aux-Barques, South Manitou

island, New Buffalo and Grassy Island at the foot of Green Bay.

Selecting a slightly elevated area on the point to the northeast of the

harbor that would make the harbor entrance visible to both up and

downbound vessels, Homans drove a stake and marked a number of trees at

the site so that it could be readily identified by the contractor that

would subsequently be chosen to build the station. Taking up the call of maritime

interests on February 19, 1838, Michigan State Representative Isaac

Crary beseeched Congress to consider funding the construction of a

lighthouse to guide vessels into Presque Isle harbor. The matter was

referred to the Committee on Commerce, and after receiving a positive

report Congress appropriated the sum of five thousand dollars for the

project on July 7, only five months after Crary introduced his

recommendation. That fall, Lieutenant James T. Homans was dispatched to

select sites for the lighthouse at Presque Isle, along with sites for

other new lights appropriated for Point-aux-Barques, South Manitou

island, New Buffalo and Grassy Island at the foot of Green Bay.

Selecting a slightly elevated area on the point to the northeast of the

harbor that would make the harbor entrance visible to both up and

downbound vessels, Homans drove a stake and marked a number of trees at

the site so that it could be readily identified by the contractor that

would subsequently be chosen to build the station.

Bids for the project were let, with

Detroit builder Jeremiah Moors awarded the contract for the station's

construction. With previous experience in lighthouse construction gained

through the construction of the station at Thunder Bay Island in 1832,

Moors' crew arrived at Presque Isle late in 1839, and over the following

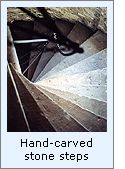

year the station's tower and dwelling slowly took shape. In accordance

with specifications, the whitewashed rubble stone tower stood 30 feet in

height with walls four feet thick at the base. The tower stood 18 feet

in diameter at the base, gracefully tapering to a diameter of 9 feet

below the gallery with a hand-cut stone stairway spiraling around the

interior wall of the tower up to the lantern. While we have as yet been

unable to identify the type of lantern and illuminating apparatus

installed, it is likely that the tower was capped with the

birdcage-style lantern and array of Argand lamps with reflectors typical

of towers of the period. The dwelling consisted of a small detached

single story structure located approximately 30 feet inshore from the

tower. Henry L. Woolsey was appointed as the station's first keeper,

officially listed in payroll records as starting service at the station

on September 23, 1840. Bids for the project were let, with

Detroit builder Jeremiah Moors awarded the contract for the station's

construction. With previous experience in lighthouse construction gained

through the construction of the station at Thunder Bay Island in 1832,

Moors' crew arrived at Presque Isle late in 1839, and over the following

year the station's tower and dwelling slowly took shape. In accordance

with specifications, the whitewashed rubble stone tower stood 30 feet in

height with walls four feet thick at the base. The tower stood 18 feet

in diameter at the base, gracefully tapering to a diameter of 9 feet

below the gallery with a hand-cut stone stairway spiraling around the

interior wall of the tower up to the lantern. While we have as yet been

unable to identify the type of lantern and illuminating apparatus

installed, it is likely that the tower was capped with the

birdcage-style lantern and array of Argand lamps with reflectors typical

of towers of the period. The dwelling consisted of a small detached

single story structure located approximately 30 feet inshore from the

tower. Henry L. Woolsey was appointed as the station's first keeper,

officially listed in payroll records as starting service at the station

on September 23, 1840.

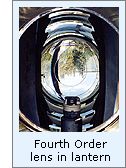

After great dissatisfaction with the

administration of lighthouses in the United States, responsibility for

the nation's aids to navigation was removed from the Treasury Department

by an Act of Congress in 1853, and transferred to the newly formed

Lighthouse Board. One of the Board's first orders of business was a

complete upgrading of the Lewis lamps with the superior French Fresnel

lenses. To this end, a work crew arrived at Presque Isle in 1857 and

installed a fixed white Fourth Order Fresnel lens. As was customary in

almost all upgrades of this type, it is likely that the old

birdcage-style lantern was simultaneously replaced by an octagonal cast

iron lantern.

By 1866, the District Inspector

reported that the keepers dwelling was in such poor condition that

nothing short of a complete rebuild would suffice to make the structure

livable, and requested that $7,000 be made available for the work.

Congress approved the requested appropriation on March 2, 1867, and some

of the materials had already been delivered to the site when the

Lighthouse Board suddenly proposed a completely different solution for

the lighting of Presque Isle in its 1868 annual report. Observing that

the combination of the tower's location and diminutive height allowed it

to function only as a harbor light, the Board suggested that an improved

solution for this important area would be to construct a larger light at

the tip of the peninsula approximately a mile to the north, and a pair

of range lights to guide vessels into the harbor itself. The Board

further suggested that with the construction of these new Lights, the

old station would be rendered obsolete, and could thereafter be

extinguished and abandoned. Estimating the cost of construction of such

a coast light to be $28,000 and $7,500 for the ranges, the Board

recommended that the amount be appropriated, and suspended the planned

repairs to the old dwelling pending Congressional action. By 1866, the District Inspector

reported that the keepers dwelling was in such poor condition that

nothing short of a complete rebuild would suffice to make the structure

livable, and requested that $7,000 be made available for the work.

Congress approved the requested appropriation on March 2, 1867, and some

of the materials had already been delivered to the site when the

Lighthouse Board suddenly proposed a completely different solution for

the lighting of Presque Isle in its 1868 annual report. Observing that

the combination of the tower's location and diminutive height allowed it

to function only as a harbor light, the Board suggested that an improved

solution for this important area would be to construct a larger light at

the tip of the peninsula approximately a mile to the north, and a pair

of range lights to guide vessels into the harbor itself. The Board

further suggested that with the construction of these new Lights, the

old station would be rendered obsolete, and could thereafter be

extinguished and abandoned. Estimating the cost of construction of such

a coast light to be $28,000 and $7,500 for the ranges, the Board

recommended that the amount be appropriated, and suspended the planned

repairs to the old dwelling pending Congressional action.

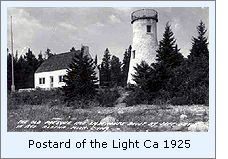

With the appropriation of the necessary

funds in 1869, work on both the Coast Light and Ranges began quickly,

with the Ranges completed at the opening of the 1870 season of

navigation and the New Presque Isle Light station completed in 1871.

Patrick Garraty Sr., who had served as keeper of the old station since

July 15, 1861 moved his wife and four children into the new station, and

exhibited its Third Order Fresnel lens for the first time on the night

of June 1, 1871. With the old light now obsolete, the station's lens and

lantern were removed from the tower and shipped to the Detroit depot for

use elsewhere. With the removal of the lantern, the tower was left

uncapped and the windows and doors to the structures boarded-up to stand

empty and decaying for 26 years until 1897 when the lighthouse

reservation and structures were finally sold at public auction to Edward

O. Avery of Alpena.

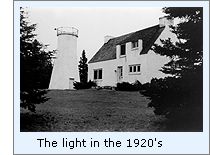

Soon after the turn of the twentieth

century, successful Lansing milliner Bliss Stebbins, and owner of the

nearby Grand Lake Hotel, purchased the property at a tax sale for

$70.00, planning to use the property as a private picnic area for

patrons of his hotel. Bliss was the brother of A. C. Stebbins who had

achieved success as the manager of the Lansing Wheelbarrow Company, and

was one of eight original founders of the Oldsmobile auto company with

Ransom Eli Olds. With the property used only as an extension of the

Grand Hotel, Bliss apparently did nothing to improve either the tower or

dwelling, and by 1930 the building's roof had collapsed, the walls were

crumbling and people were seen stealing bricks to use in their back yard

projects. Soon after the turn of the twentieth

century, successful Lansing milliner Bliss Stebbins, and owner of the

nearby Grand Lake Hotel, purchased the property at a tax sale for

$70.00, planning to use the property as a private picnic area for

patrons of his hotel. Bliss was the brother of A. C. Stebbins who had

achieved success as the manager of the Lansing Wheelbarrow Company, and

was one of eight original founders of the Oldsmobile auto company with

Ransom Eli Olds. With the property used only as an extension of the

Grand Hotel, Bliss apparently did nothing to improve either the tower or

dwelling, and by 1930 the building's roof had collapsed, the walls were

crumbling and people were seen stealing bricks to use in their back yard

projects.

Bliss's brother, Francis B. Stebbins,

purchased the property in 1930, planning to rebuild the dwelling as a

summer cottage for his family, however finding the structure to be

unsalvageable he came to the same decision as the District Inspector

some 70 years previous, deciding to demolish the structure and start

anew. After dynamiting the crumbling walls, Stebbins finished work in

1939, with the structure built in a style reminiscent of an old English

cottage. Bliss incorporated many interesting materials in the

construction, notable among them were the cottage's flagstone floors and

ceiling beams which were salvaged from the old Lansing post office which

was being replaced at the time. With no electricity available on the

property, power was supplied by a 32 volt DC Delco generating plant

located in the cellar. Bliss's brother, Francis B. Stebbins,

purchased the property in 1930, planning to rebuild the dwelling as a

summer cottage for his family, however finding the structure to be

unsalvageable he came to the same decision as the District Inspector

some 70 years previous, deciding to demolish the structure and start

anew. After dynamiting the crumbling walls, Stebbins finished work in

1939, with the structure built in a style reminiscent of an old English

cottage. Bliss incorporated many interesting materials in the

construction, notable among them were the cottage's flagstone floors and

ceiling beams which were salvaged from the old Lansing post office which

was being replaced at the time. With no electricity available on the

property, power was supplied by a 32 volt DC Delco generating plant

located in the cellar.

In the 1940's, Francis purchased a

larger summer home nearby, and continued to use the cottage by the

lighthouse as a guest house. After a number of vacationers began asking

for tours of the old light station, Francis realized that converting the

property into a museum might be a financially rewarding opportunity, and

he set about refurbishing the old tower, which had sustained a

considerable amount of water damage as a result of being uncapped for 70

years. Missing cement was replaced between the stones where it had

washed-out, the structure was given a fresh coat of white paint and a

chain handrail was installed up the center of the stairs at the request

of Stebbins' insurance carrier. Francis heard through the grapevine of an auction being held by the Coast Guard in the

early 1950's, and successfully bid on two Fresnel lenses, which he

brought back to the station. Wishing to install one of them in the

tower, arrangements

were made with a fabricator in Alpena to build a replica octagonal iron

lantern similar to that which was installed on the tower in 1957. The

completed lantern was hoisted atop the tower, and the smaller of the two lenses,

a Fourth Order lens with twin bulls eyes and brass occulting panels was

installed in the lantern.

The old English cottage was furnished

with items appropriate to the mid-nineteenth century period, and various

other maritime artifacts were obtained for display in the cottage and on

the grounds. Electricity finally came to the station in 1965, and

Francis reactivated the light in the tower. However the Coast Guard

would not provide permission for its continued display as a private aid,

and the clockwork rotating mechanism was removed from beneath the lens.

Francis B Stebbins passed away in 1969,

and the property transferred to his son Jim, who continued to operate

the station as a museum. Jim applied for National Register of Historic

Sites status for the station, and the tower being added to the registry

in 1973. Hiring vacationing college girls to serve as guides at the

station, the girls wore nineteenth century period clothes to further the

illusion of a "step back in time." Unfortunately, the college

girls appeared to have acted as a magnet for college boys, and in 1977

Jim made the decision to hire a retired couple George and Loraine Parris

as live-in tour guides and custodians. Francis B Stebbins passed away in 1969,

and the property transferred to his son Jim, who continued to operate

the station as a museum. Jim applied for National Register of Historic

Sites status for the station, and the tower being added to the registry

in 1973. Hiring vacationing college girls to serve as guides at the

station, the girls wore nineteenth century period clothes to further the

illusion of a "step back in time." Unfortunately, the college

girls appeared to have acted as a magnet for college boys, and in 1977

Jim made the decision to hire a retired couple George and Loraine Parris

as live-in tour guides and custodians.

The second Fresnel lens purchased in

the 1950's was displayed in the cottage. Mounted on wheels, it was

rolled out onto the patio on sunny days, where it shone like a huge

piece of jewelry. Unfortunately, Jim became aware that this was not the

best way to display the lens, as the litharge began to break down and

the glass segments became loose, and the lens thereafter remained on

display in the cottage. Soon after the Charlevoix School District

obtained ownership of the Beaver Head Light station in 1979, a

representative of the District approached Jim, inquiring if he might be

interested in selling them the lens for installation in the Beaver Head

tower. Jim decided to donate the lens, and it was packaged-up and

shipped to Beaver Island where it is displayed to this day at the base

of the tower.

George Parris passed away in 1992, and

Lorraine continued to serve as the custodian. As a result of increasing

taxes and insurance costs, Jim Stebbins sold the property to the State

of Michigan to be incorporated into the State Park, and donated the

structures to the Township in 1995. The Township Historical Society

continues to operate the lighthouse as a museum to this day from May

through October. The museum is open seven days a week from 9 a.m. To 6

p.m. George Parris passed away in 1992, and

Lorraine continued to serve as the custodian. As a result of increasing

taxes and insurance costs, Jim Stebbins sold the property to the State

of Michigan to be incorporated into the State Park, and donated the

structures to the Township in 1995. The Township Historical Society

continues to operate the lighthouse as a museum to this day from May

through October. The museum is open seven days a week from 9 a.m. To 6

p.m.

Local lore reports that the deactivated light in the tower has been

seen illuminated at night, and many believe that George Parris returns to reactivate

it, but that is a story of a type on which we are unqualified to

comment.

Keepers of

this Light

Click here

to see a complete listing of all keepers of the Presque Isle Old Light

compiled by Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Finding this Light

Take US23 South from Rogers City, and turn east on 638 Hwy/Highway Road.

Continue to the point at which the road splits, and take the left fork

when the road splits, staying on 638 Hwy. Continue for approximately 2

miles, and turn North on Grand Lake Road. Continue approximately one

mile until you reach the shore of the Lake. Continue North for 1/4 mile,

and the entrance to the lighthouse park is on the right. Park in one of

the spaces between the trees, and walk to the end of the point to the

lighthouse.

Contact information

Old Presque Isle Lighthouse

5295 Grand Lake Road

Presque Isle, MI 49777

(989) 595-2787

Reference Sources

Congressional

records, various Congressional

records, various

Annual

reports of the Fifth Auditor of the Treasury, 1838 - 1952, various.

Annual

reports of the Lighthouse Board, 1852 - 1897, various

Inventory of Historic

Light Stations, National Parks Service, 1994

Northern Lights, Charles K Hyde, 1995

Interview with Jim Stebbins, Monday March 25, 2002.

Aerial photograph courtesy of Marge Beaver of Photography Plus

Personal observation at Presque Isle, 09/11/1998

Photographs from the author's personal collection.

Historic photographs from the Michigan State Archives.

Keeper listings for this light appear courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|