|

Historical Information

With the major landmarks and

dangers on the US side of Lake Huron already illuminated, in the final

decades of the nineteenth century the Lighthouse Board turned its

attention to creating a system of coast lights along the lake's western

shore. In creating such a system, the Board planned to strategically

located a series of lighthouses along the coastline in such a way that

mariners would always be within sight of one light of the series.

While the Presque Isle Peninsula had

been lighted since 1840, and the entrance to the Cheboygan River fifty

miles to the north had been lighted since 1851, the New Presque Isle

Light's range of visibility of 19 miles and the Cheboygan Light's

visible range of 13 miles left an unlighted 18 mile intervening stretch

of coastline along which mariners were forced to navigate blind. In it's

annual report for fiscal 1890, the Board recommended that $25,000 be

appropriated for the construction of a new light and fog signal at Forty

Mile Point near Hammond's Bay, at the approximate mid point between the

two lights.

Congress appears to have been

unconvinced of the need to create such a system of contiguous coast

lights, as a similar request for the funds to construct the light at

Port Sanilac in 1869 had languished unresolved for 16 years before

Congress finally provided the necessary appropriation in 1885. With this

in mind, it is not surprising that the matter of the Light at Hammond's

Bay remained unresolved until February 15, 1893, when Congress finally

authorized the project, but failed to provide the necessary

appropriation. The Board again requested funding in its 1894 annual

report, with Congress freeing-up the funds as part of the Sundry Civil

Appropriations Act of August 18, 1894.

Eleventh District Engineer Major Milton

B. Adams selected and surveyed the site for the new Light. With an offer

of $200 for the property accepted by the owner, Adams approved the plans

and specifications for the station in February 1896. Contracts for the

ironwork for the lantern, gallery, boilers and fog whistles were awarded

soon thereafter, and with receipt of the materials at the Detroit depot,

were loaded aboard the lighthouse tender AMARANTH and delivered to the

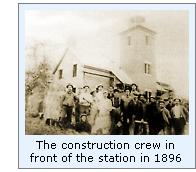

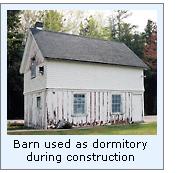

site on July 5, 1896. Work at the site began with the construction of a

wood-framed building, which would be used by the work crew as a

temporary dwelling during construction, and converted into a barn for

the keeper's horses on the completion of the work. Eleventh District Engineer Major Milton

B. Adams selected and surveyed the site for the new Light. With an offer

of $200 for the property accepted by the owner, Adams approved the plans

and specifications for the station in February 1896. Contracts for the

ironwork for the lantern, gallery, boilers and fog whistles were awarded

soon thereafter, and with receipt of the materials at the Detroit depot,

were loaded aboard the lighthouse tender AMARANTH and delivered to the

site on July 5, 1896. Work at the site began with the construction of a

wood-framed building, which would be used by the work crew as a

temporary dwelling during construction, and converted into a barn for

the keeper's horses on the completion of the work.

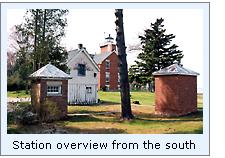

Adams'

plan for the main lighthouse structure was a virtual duplicate of that

simultaneously under construction at Big Bay Point on Lake Superior.

Consisting of a duplex dwelling with a tower incorporated into the

center of one side-wall, the structure stood 35 feet by 57 feet in plan.

Erected on a 20" thick cut limestone foundation, the brick walls

featured double walls with an air space between to provide insulation.

The integrated tower stood twelve feet in plan, and fifty-two feet in

height. The apartments on each side of the dwelling were exact mirrored

duplicates and were set-up to afford complete privacy. Each apartment

featured its own main entry, cellar, kitchen, parlor, tower entry door

and stairway to the bedrooms on the second floor. Indicative of Adam's

thoughtfulness in designing the structure, each of the stairways

incorporated a skylight in its ceiling through which the lantern could

be observed, thereby allowing both keeper and his assistant to verify

the correct operation of the light from within the warmth of their

apartment without having to leave the building or climb to the top of

the tower itself to see the light. The brick tower was capped by a

square gallery with iron safety railing, and a prefabricated octagonal

cast iron lantern erected at its center. Adams'

plan for the main lighthouse structure was a virtual duplicate of that

simultaneously under construction at Big Bay Point on Lake Superior.

Consisting of a duplex dwelling with a tower incorporated into the

center of one side-wall, the structure stood 35 feet by 57 feet in plan.

Erected on a 20" thick cut limestone foundation, the brick walls

featured double walls with an air space between to provide insulation.

The integrated tower stood twelve feet in plan, and fifty-two feet in

height. The apartments on each side of the dwelling were exact mirrored

duplicates and were set-up to afford complete privacy. Each apartment

featured its own main entry, cellar, kitchen, parlor, tower entry door

and stairway to the bedrooms on the second floor. Indicative of Adam's

thoughtfulness in designing the structure, each of the stairways

incorporated a skylight in its ceiling through which the lantern could

be observed, thereby allowing both keeper and his assistant to verify

the correct operation of the light from within the warmth of their

apartment without having to leave the building or climb to the top of

the tower itself to see the light. The brick tower was capped by a

square gallery with iron safety railing, and a prefabricated octagonal

cast iron lantern erected at its center.

A pair of brick privies were erected to

the rear of the dwelling flanking the barn, and a well was sunk and

equipped with a windmill-operated pump, which discharged water into an

elevated tank to provide a supply of drinking water to the station. The

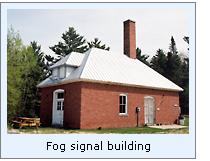

brick fog signal building was erected approximately 290 feet southeast

of the lighthouse. Outfitted with twin boilers installed on raised

concrete pads, the boilers were piped to duplicate 10" steam

whistles located on the lakeside wall and exhausted through a pair of

iron smokestacks. A pair of brick privies were erected to

the rear of the dwelling flanking the barn, and a well was sunk and

equipped with a windmill-operated pump, which discharged water into an

elevated tank to provide a supply of drinking water to the station. The

brick fog signal building was erected approximately 290 feet southeast

of the lighthouse. Outfitted with twin boilers installed on raised

concrete pads, the boilers were piped to duplicate 10" steam

whistles located on the lakeside wall and exhausted through a pair of

iron smokestacks.

A 120-foot long T-shaped dock was

erected between the fog signal building and the dwelling, with a

boathouse for the Keeper's boat erected at its shore end. An iron-railed

tramway led from the dock, across post supports to the shore to the fog

signal building and thence behind the dwelling to the barn for the

transportation of coal and supplies delivered by lighthouse tenders

during their semi-annual supply visits. Finally, plank sidewalks were

laid connecting all of the station's structures to provide easy and safe

access to the keepers.

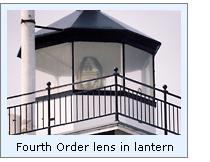

The Eleventh District Lampist arrived

from Detroit, and carefully assembled the Fourth Order Fresnel lens atop

a cast iron pedestal within the lantern. Designed and manufactured by

Henry-Lepaute in Paris, the lens was equipped with six

bulls-eye flash panels. Powered by a clockwork mechanism, the lens was

designed to be rotated around the lamp at a carefully regulated speed in

order to emit the station's specified characteristic white flash every

ten seconds. The Eleventh District Lampist arrived

from Detroit, and carefully assembled the Fourth Order Fresnel lens atop

a cast iron pedestal within the lantern. Designed and manufactured by

Henry-Lepaute in Paris, the lens was equipped with six

bulls-eye flash panels. Powered by a clockwork mechanism, the lens was

designed to be rotated around the lamp at a carefully regulated speed in

order to emit the station's specified characteristic white flash every

ten seconds.

With construction completed on November

12, 1896 and winter setting in, it was deemed too late in the year to

activate the Light. Thus, a caretaker was hired to live in and watch

over the building until the appointment of a Keeper and Assistant at the

opening of the following navigation season. Xavier Rains, who had been

served for a year as Keeper of the Round Island Light in the St. Mary's

River was selected as Keeper, and Edward Lane was promoted from his

position as Second Assistant at Devils Island to Assistant at Forty Mile

Point. Both Rains and Lane first appear on payroll records at Forty Mile

Point on January 4, 1897. It is therefore likely that they arrived at

the station on this date, and after preparing the station for operation,

exhibited the Forty Mile Point Light for the first time on the night of

May 1, 1897. With construction completed on November

12, 1896 and winter setting in, it was deemed too late in the year to

activate the Light. Thus, a caretaker was hired to live in and watch

over the building until the appointment of a Keeper and Assistant at the

opening of the following navigation season. Xavier Rains, who had been

served for a year as Keeper of the Round Island Light in the St. Mary's

River was selected as Keeper, and Edward Lane was promoted from his

position as Second Assistant at Devils Island to Assistant at Forty Mile

Point. Both Rains and Lane first appear on payroll records at Forty Mile

Point on January 4, 1897. It is therefore likely that they arrived at

the station on this date, and after preparing the station for operation,

exhibited the Forty Mile Point Light for the first time on the night of

May 1, 1897.

Within a year, problems were

experienced with the drinking water supply, and a work crew arrived at

the station to construct a new foundation, elevated support frame for

the water tank, and completely replaced the water supply piping leading

into the dwelling. In November 1900, the posts supporting the tramway

from the dock to the shore were found to have deteriorated

significantly, and were replaced by five substantial timber cribs filled

with stone, and a log retaining wall was built along the sand bank

behind the boathouse to stem erosion. Within a year, problems were

experienced with the drinking water supply, and a work crew arrived at

the station to construct a new foundation, elevated support frame for

the water tank, and completely replaced the water supply piping leading

into the dwelling. In November 1900, the posts supporting the tramway

from the dock to the shore were found to have deteriorated

significantly, and were replaced by five substantial timber cribs filled

with stone, and a log retaining wall was built along the sand bank

behind the boathouse to stem erosion.

1901 saw the busiest year at the

Forty-Mile Point fog signal station, with the whistles kept operating

for a total of 274 hours, and consuming 7 tons of coal. By 1905, the

twin iron smokestacks on the fog signal building were so badly rusted

and decayed that they were replaced by a single, three-foot square brick

chimney into which both boilers were exhausted.

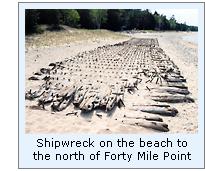

On

October 19, 1905, the Lake was assaulted by fierce storms, and twenty

seven wooden ships went down, with an accompanying loss of fifty lives.

The wooden hulled steamer JOSEPH S. FAY was Southbound, towing the

schooner barge D. P. RHODES, when the storm caused the RHODES to break

free, dragging with her a portion of the FAY's stern. Finding his vessel

to be sinking, the Captain of the FAY turned toward shore, only to catch

her bow on a sandbar, swinging her around into the oncoming sea, ripping

off the forward cabin. The Captain and ten crewmen were carried to shore

safely within the cabin. Two crewmen made it to shore alive, but the

First Mate was not so fortunate, His body was found on the beach about a

mile to the north almost two months later. On

October 19, 1905, the Lake was assaulted by fierce storms, and twenty

seven wooden ships went down, with an accompanying loss of fifty lives.

The wooden hulled steamer JOSEPH S. FAY was Southbound, towing the

schooner barge D. P. RHODES, when the storm caused the RHODES to break

free, dragging with her a portion of the FAY's stern. Finding his vessel

to be sinking, the Captain of the FAY turned toward shore, only to catch

her bow on a sandbar, swinging her around into the oncoming sea, ripping

off the forward cabin. The Captain and ten crewmen were carried to shore

safely within the cabin. Two crewmen made it to shore alive, but the

First Mate was not so fortunate, His body was found on the beach about a

mile to the north almost two months later.

Four years after assuming

responsibility for the nation's aids to navigation, Commissioner of

Lighthouses Charles R Putnam made the startling revelation that the

Forty Mile Point Light had been built in the wrong location. In his 1913

annual report to Congress, he stated that the county survey charts used

in selecting the site in 1896 were in error, and that vessel masters

expected the lighthouse to be erected at Nine Mile Point, some 20 miles

to the northeast, where a total of nine strandings had occurred between

1903 and 1909. With Eleventh District Inspector E L Woodruff's 's

estimate that a new Light and fog signal could be built at Nine Mile

Point for $50,000, Putnam suggested that with the appropriation, the

Forty Mile Point Light could be downgraded, and the fog signal

eliminated. After Putnam reiterated the request for the appropriation in

his 1914 annual report, Congress responded turned down the request, and

Putnam forever abandoned the cause.

That same year, on July 10, 1914, the

illuminating apparatus at Forty Mile Point was upgraded to an

incandescent oil vapor (I.O.V) system with an increase in intensity to

55,000 candlepower and a resulting increase in the Light's visible range

to 16 miles. That same year, on July 10, 1914, the

illuminating apparatus at Forty Mile Point was upgraded to an

incandescent oil vapor (I.O.V) system with an increase in intensity to

55,000 candlepower and a resulting increase in the Light's visible range

to 16 miles.

1931 saw the removal of the steam

whistles from the fog signal building and the installation of a pair of

Type F diaphones, representing a significant improvement in both the

audible range and speed at which the signals could be activated.

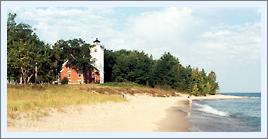

The station was automated in 1969, and

is now part of a county park and one half of the dwelling has been

turned into a museum, and the other half as quarters for the caretaker.

The tower has been opened to the public, and visitors can climb the

stairs to view the Fourth Order lens close up and enjoy the view across

Lake Huron.

Keepers of

this Light

Click here

to see a complete listing of all Forty Mile Point Light keepers compiled

by Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Finding this Light

Go North from Rogers City on US23 approximately 6 miles to the entrance

to the Presque Isle County Lighthouse Park. The entrance is on the East

side of the road, and is signed. Drive down the narrow tree-lined

entrance to the park to the Lake. There is a parking area behind the old

fog signal building, and the lighthouse is to the North. Also walk to

the beach and continue North a few hundred yards to see the remains of

the wooden hulled steamer Joseph S. Fay.

Contact information

The lighthouse is now operated by the 40 Mile Point Lighthouse Society,

and the grounds are open to the public year round from 10.00 AM to 10.00

PM. The

lighthouse itself if open on weekends between Memorial Day through mid

October. For

specific information on open hours, telephone the Rogers City Chamber of

Commerce at

(800) 622-4148.

Membership

in the 40-Mile Point Lighthouse Society is only $20.00 per year, and the

Society may be reached at:

40 Mile Point Lighthouse

Society

PO Box 205

Rogers City, MI 49779

Or visit the Society's website at

www.40milepointlighthouse.org

Reference Sources

Annual reports of the Lighthouse

Board, various, 1890 - 1909

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Service, 1910-1920

Annual report of the Lake Carrier's Association, 1913

Inventory of Historic

Light Stations, NPS, 1994

Northern Lights, Charles K. Hyde, 1995

USCG Historian's Office -

photographic archives.

Personal observation at Forty Mile Point, 09/11/1998

Photographs from the author's personal collection.

Keeper listings for this light appear courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|